Photo by Mashburn Photo

“Conviviality is healing. To be healed we must come with all the other creatures to the feast of Creation.

— Wendell Berry, The Body and the Earth

“Do you want an egg?” asked Rafael Rios.

“No, thank you. I ate breakfast already.”

I was being polite.

So was he.

“Look at these duck eggs,” he said, showing me the full bucket, dirt from the yard still clinging to shells the hue of green tea and honeydew.

I hesitated.

“Let me cook you one.”

He grabbed a frying pan and turned on the stove in the kitchen at his father’s farmhouse, a few miles outside Little Flock, in Benton County, Arkansas. Cracked the egg, let it sizzle. Flipped a handmade corn tortilla on the open flame of another burner until the edges scorched. Slid a plate across the counter to where I sat, fork ready. Duck eggs are big, creamy, and usually have a deep orange yolk. I sopped up the runny parts with torn pieces of tortilla, and thought about asking for more, to clean the pooling hot sauce.

Maybe he read my mind.

“You want another tortilla?”

“Yes, please.”

The Rios Family - Photo by Mashburn Photo

After I finished, we went outside to greet the flock of ducks pecking around the muddy driveway, and his blue heeler Chente, named for ranchera music legend Vicente Fernández, trotted along. The Rios family arrived in this part of the Ozarks from California in 2006, and their patriarch Hector, nicknamed Yeyo, started growing vegetables on seven acres for home use, but eventually for a food truck Rafael launched six years later. He got an expansion loan to open a taco restaurant, then a mezcaleria, and earlier this year was named a semifinalist for the James Beard Foundation’s Best Chef: South award. The 44-year-old Army veteran stopped at a makeshift grill in the side yard, and outlined plans to build a proper barbacoa pit this summer. I easily imagined sparks drifting into the night sky, and gusts of laughter as friends sat in folding chairs, holding chilled Modelo longnecks, while children chased the farm dogs around the hoop houses and blackberry patch. Rafael promised to trade an earthenware cazuela bean pot for one of my cast iron skillets, and we shook hands to say goodbye.

That was then.

Only a month ago.

Rafael Rios with his dogs and chickens - Photo by Mashburn Photo

A yellowed photograph stands out in the albums belonging to my grandfather, James Murray Mitchell, who used his Kodak No. 2 Autographic Folding Brownie camera to document family life on Edisto, one of the Carolina Sea Islands, right after he returned from serving in the Coast Guard during World War I, and just as the Spanish flu pandemic circled back around for a second time to finish killing millions worldwide. You wouldn’t know it from his photographs. Fishing trips, sailboat races, picnic expeditions to the beach, beloved dogs, a horse named May, chickens in the yard. My family was isolated from the mainland.

Like most Sea Islanders, they were self-sufficient, which would also serve them well later, during the Depression’s food shortages. Had to create their own fun when afforded opportunities to break from the mundane tasks of managing a farm owned by wealthier relatives up in Charleston. House parties lasted weeks, when guests “from off” landed for a visit. Church followed by supper on a long table set under the live oaks. A tabby limestone cistern under the house kept drinks cool for cocktails on the porch. My grandfather particularly liked taking portraits, and some of the posed groups are my most treasured record of a complex and tightly knit lineage. My Nana was a second cousin who lived next to the landing where supplies were delivered to her father’s store when steamboats docked every week or so. She looked so pretty modeling a flapper-style bathing costume, lounging on dunes with her sisters and his brothers and the other cousins. My grandfather also commemorated the older generation, who were born before the Civil War.

Which brings me to that photograph.

Photo courtesy of Shane Mitchell

She is wearing a brimmed hat that obscures her face. Boots peek out from underneath an ankle-length skirt. Hands rest in her lap, covered by an apron. A corsage seems to be pinned to the oversized collar of her white blouse, with cuffs turned up over a darker jacket. The clothes look too big on her. Hard to tell her age, but if she was more than 55 years old, her life was deeply complicated by history. In my grandfather’s elegant handwriting, the caption reads: “Old Julia.”

The cook.

Someone had to do the hard work in a hot kitchen removed from the main house. Bake pies for that Sunday meal. Pack sandwiches for those beach picnics. Ferment berries for the shrubs and cordials sipped on the porch. Crack and pick the meat for the devilled crabs my grandfather loved. This unequal division of labor was already in place hundreds of years before, but it seems too simplistic to say they were a product of their times. Chances are Old Julia lived across the tidal creek in a row of dilapidated cabins next to fields where Sea Island cotton was grown before the war and the weevil changed all that.

One of those cabins is now in the Smithsonian.

On March 6, 1820, the 36°31′ north parallel became the dividing line between free soil states in the North and slave-holding states in the South, when the Missouri Compromise set the stage for an ongoing stereotypical identity rift, especially in popular culture. (Our food is full of it: Colonel Sanders, Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben.) The first located use of the phrase “southern hospitality” as associated with antebellum society appeared in 1835, by author and educator Jacob Abbott, who portrayed Southerners as generous and open-hearted in his rambling anthology “New England, and Its Institutions.” He wrote:

You enter the house. The best it affords is at your service. At once you are at home. Conversation flows cheeringly, for the southern gentleman has a particular tact in making a guest happy. After dinner you are urged to pass the afternoon and night, and if you are a gentleman in manners and information, your host will be in reality highly gratified by your doing so. Such is the character of southern hospitality.

Nice for some.

This was the era when three foundational Southern cookbooks — The Virginia Housewife (1824), The Kentucky Housewife (1839), and The Carolina Housewife (1847) — were published. But it was the enslaved who were essential to the creation of the South’s culinary heritage, and the recipes in these collections, revised and adapted in later texts, reflect the meals that cooks in bondage prepared at the direction of these housewives, rather than for their own families. Mary Boykin Chestnut chronicled plantation life in her diaries during the Confederacy; her account ranged from political commentary to domestic management of multiple households and landholdings with 1,000 enslaved people. One passage from March 22, 1861 is telling with regard to this dietary inequity.

I was mobbed by my own house servants yesterday….They agreed to come to me in a body and beg me to stay at home, to keep my own house once more, and said I ought not to have scattered and distributed them every which way….I asked my cook if she lacked for anything on the plantation at the Hermitage.

“Lack anything? I lack everything. What is cornmeal and bacon, milk and molasses? Would that be all you wanted? Ain’t I bin living and eating exactly as you does all these years? When I cook fer you didn’t I have some of all? Dere now!”

Domestic Cook Book: Containing a Careful Selection of Useful Receipts for the Kitchen 1866

It is also telling that the first cookbook published by a free African-American woman appeared in 1866. Malinda Russell, who operated a boarding house and then a pastry shop in Greenville, Tennessee, wrote A Domestic Cook Book. Most of her recipes wouldn’t be strictly categorized as Southern by modern standards, but she does include mush cake, sweet potato pie, green corn bread, pickled peaches, and fricasseed catfish, all hallmarks of what would eventually come to be classified as soul. Her recipe for Burst-Up Rice has African roots. (Only recently have contributions to the Southern recipe canon of African, Caribbean, and Native American peoples been properly acknowledged.) It is significant that Russell references The Virginia Housewife in her first chapter, “Rules and Regulations of the Kitchen.” She wrote:

I have made Cooking my employment for the last twenty years, in the first families of Tennessee, (my native place), Virginia, North Carolina, and Kentucky. I know my receipts to be good as they have also given satisfaction….Being compelled to leave the South on account of my Union principles, in the time of the Rebellion, and having been robbed of all my hard-earned wages which I had saved; and as I am now advanced in years, with no other means of support than my own labor; I have put out this book with the intention of benefiting the public as well as myself.

Jim Crow laws and segregation would keep people from sitting down together over a meal into the next century. And let’s be honest. That inhospitable codification remains.

Don’t it always seem to go

That you don’t know what you’ve got

’Till it’s gone

— Joni Mitchell, Big Yellow Taxi

Even Waffle Houses are closing.

No picnics on the beach or suppers under a live oak for this pandemic either. Corner grocery po-boys and fried chicken dinners. The ice cream truck and the tamale cart. The backyard barbecue. The tailgate party. Tomato festivals. Boiled peanut stands. The Miss Vidalia Onion pageant. All cancelled.

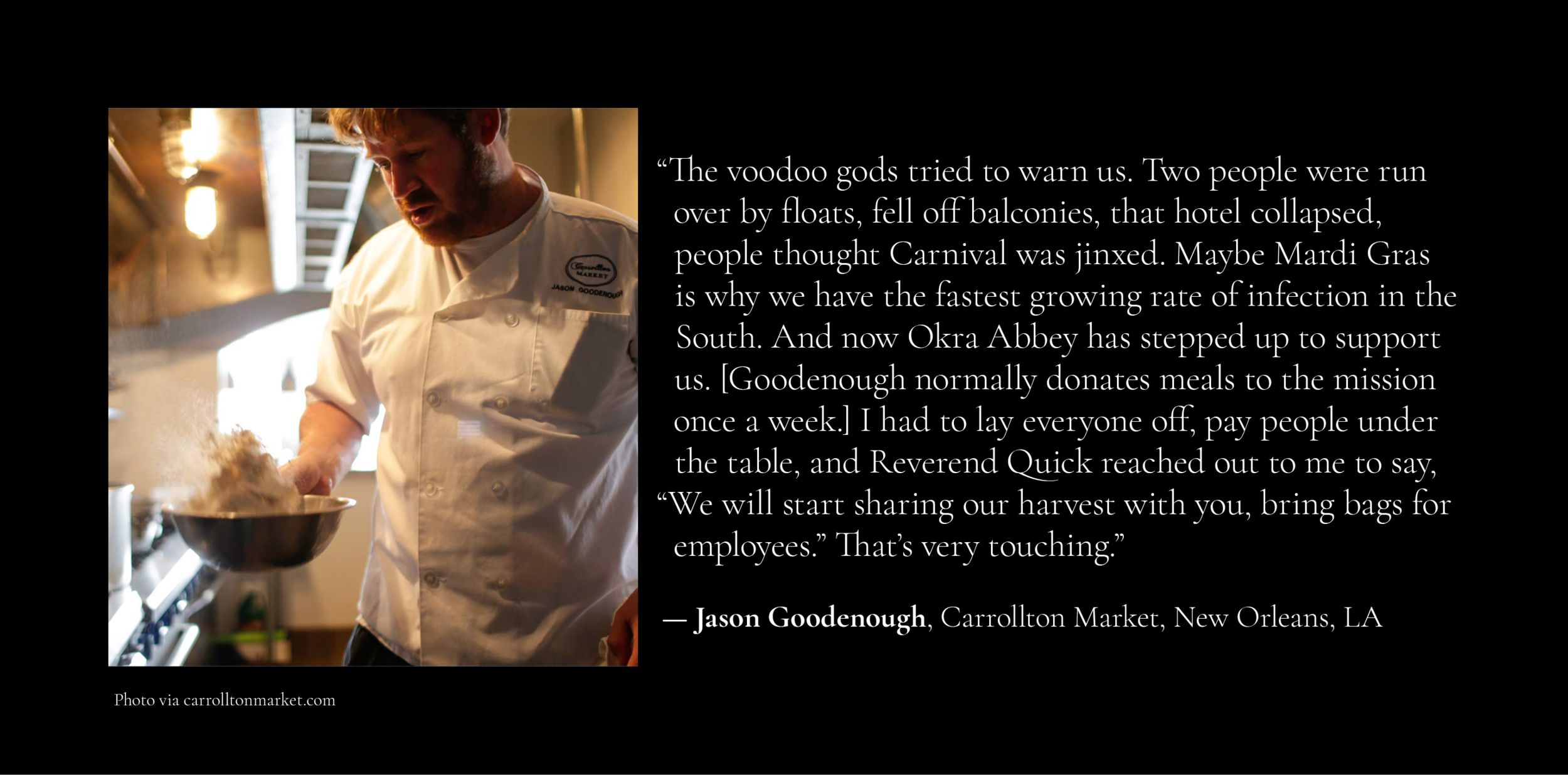

Since returning home from Arkansas, I’ve grappled with what Southern hospitality means now, even as who identifies as a Southerner has also evolved. Despite its problematic roots, Southerners are inextricably tied to the humble act of sharing something to eat or drink. That may prove to be our downfall or our salvation. Who guessed a lethal viral outbreak would so rapidly shutter our most beloved dining institutions, possibly forever? On Instagram, activist chef Tunde Wey is posting about the unethical aspects of a restaurant industry tied to underpaid labor, Big Ag, gentrification, and predatory development: “Let it die.”

Mike Costello & His rooster, “Red”. photo courtesy of @costellowv on twitter

Farm and Supper Club chef and farmer Mike Costello of West Virginia’s Lost Creek Farm uploaded a selfie holding his prize rooster on Twitter: “Red and I now share a seat on this emotional roller coaster, and we’ve reached a moment we didn’t see coming for another two, maybe three, years. No way around it — one of us will get to/have to eat the other to survive. Tomorrow we draw straws.” A day later he posted an update: “Walmart out of straws this morning. Decision delayed 8 wks, minimum.”

Others reacting to the pandemic have pivoted to ghost kitchens. Some have made the conscious sacrifice to feed their staff rather than pay mortgages. Ashley Christensen formed the North Carolina Restaurant Workers Relief Fund. Edward Lee launched the Lee Initiative, turning restaurants into aid centers, offering hot meals and other supplies. In the D.C. suburb of Arlington, Virginia, Bayou Bakery’s David Guas partnered with Blue Star Families and Real Food for Kids to distribute free plant-based lunches to school children in need, no questions asked. In New Orleans, the Krewe of Red Beans started Feed the Frontline: Venmo donations pay to deliver meals from local restaurants for hospital workers. In Kentucky, Rabbit Hole Distillery is one of many that has switched from producing small-batch bourbon to hand sanitizer. Chris Shepherd’s Southern Smoke Foundation posted links to mental health resources, legal advice, unemployment services. The Houston Shift Meal network is making sure no waiter goes hungry.

Farmers who supplied restaurants have also found themselves deep in the weeds. Gabrielle Eitienne is one of the creators behind Tall Grass Food Box, a new CSA collective of Black farmers in the Raleigh-Durham area hoping to spread a message about self-determination and food sovereignty. Lowcountry Street Grocery, operating out of a converted school bus named Nell, has shifted to home delivery in Charleston neighborhoods with high food insecurity, supplying produce from their network of local farmers to those falling through the cracks of social services. The Crescent City Farmers Market has temporarily re-organized as a drive-through/no contact pop-up in a parking lot and partnered with non-profit Top Box Foods to deliver affordable groceries to needier parishes.

Click the Images to Scroll

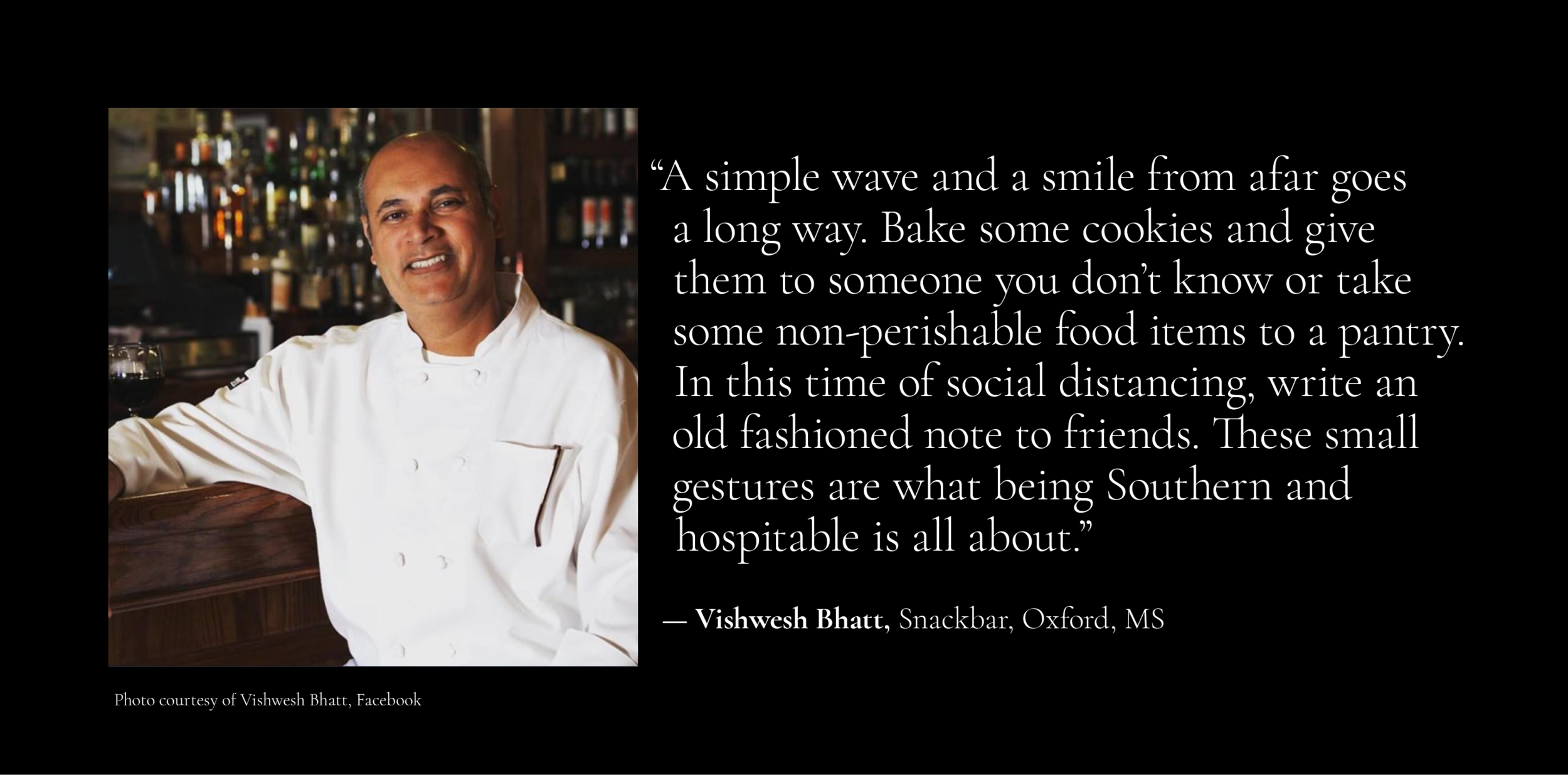

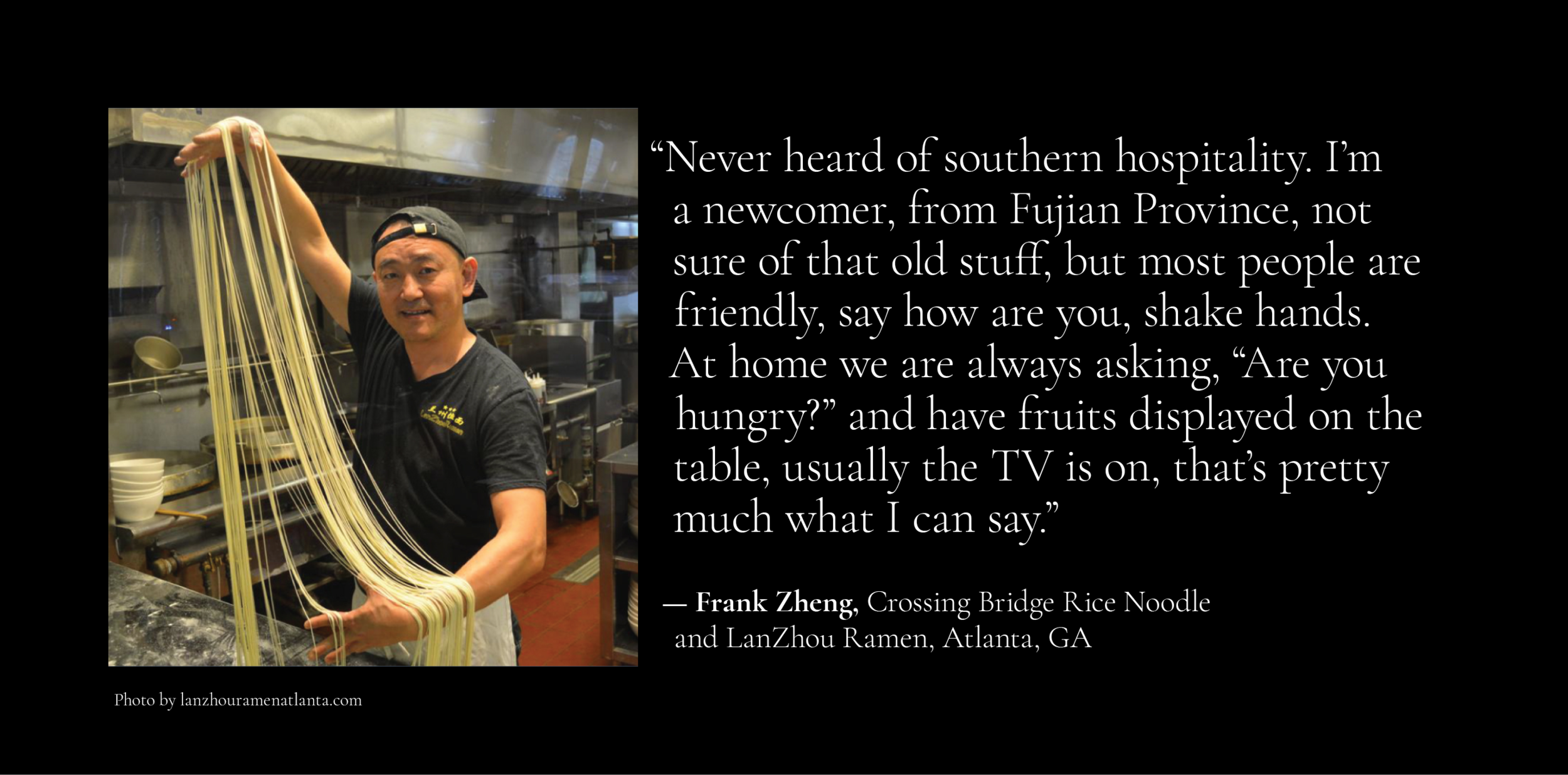

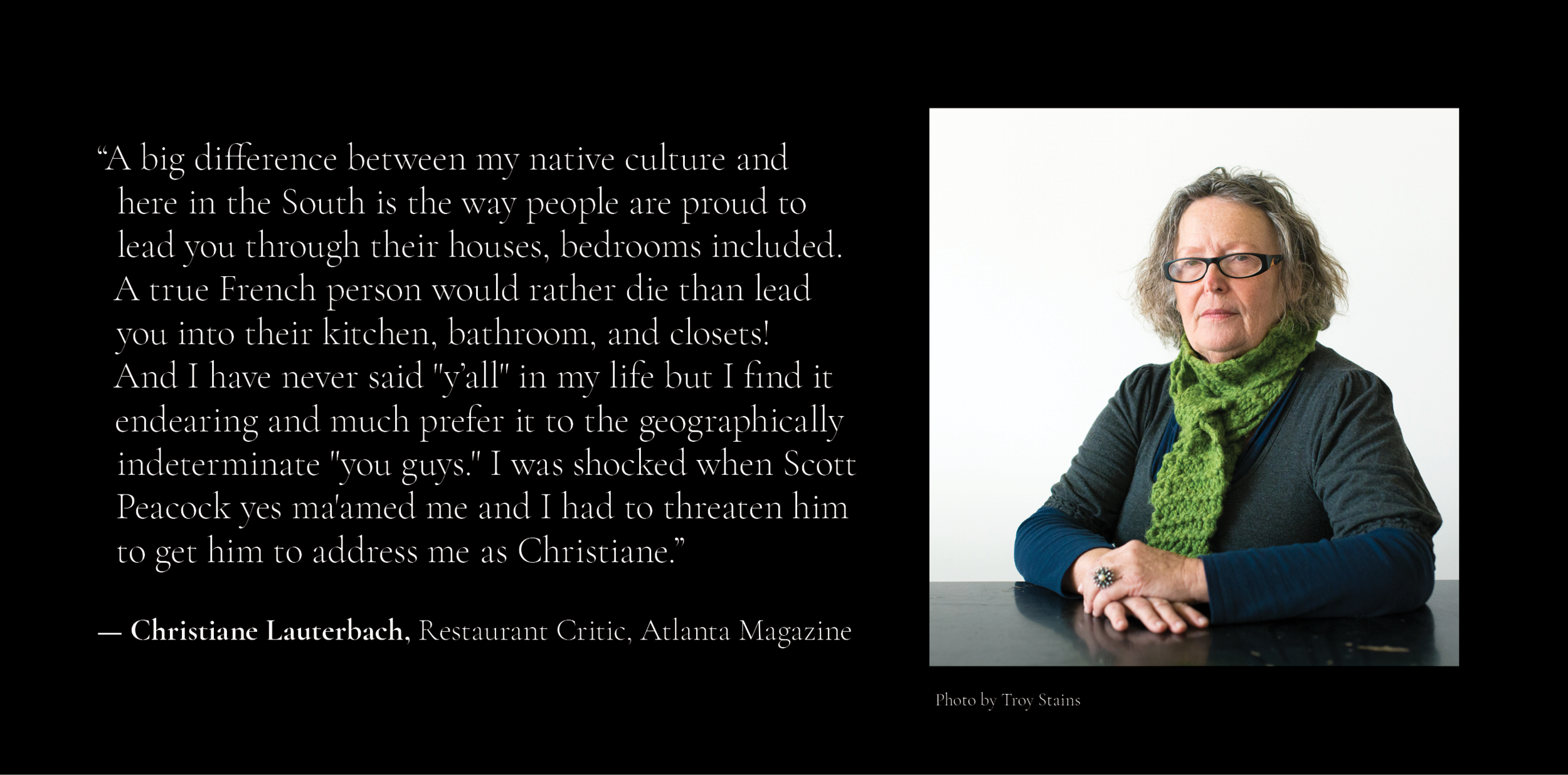

Wrestling with a catastrophe at a social distance was too much for one person to bear, so I reached out to others all along the food chain below that 36º31' parallel — chefs, farmers, wait staff, grocers, pitmasters, bartenders — to ask if they could help redefine Southern hospitality for this moment. The ones who fill up that glass of sweet tea; the ones who grow those watermelons; the ones who bake those pies; the ones who offer the eucharist and pray over the bread of affliction. The ones who feed us. Their answers ranged from tearful to funny as hell, even as they cope with trauma and loss of livelihood. Unsurprisingly of those dedicated to service, they all tried to offer comfort, and that is a universal construct without borders.

While I’m not the praying sort, it also wasn’t lost on me that spring is one of those converging moments in the world holy calendar when so many people gather to give thanks over a meal. When the Right Reverend Robert C. Wright, the first African-American to be ordained bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Atlanta, arrived in 2002 from New York City, parishioners welcomed him in typical fashion.

“Among the born-and-raised Southerners, there was some concern that I did not gain any weight,” he said. “I was so busy greeting the newcomers after worship and did not sit down at a table and eat. That was a conversation. They were not happy unless I was walking out with enough aluminum foil to reflect the sun rays.”

Wright admitted he learned a lesson from his church ladies and their covered dishes.

“Southerners have a high sensitivity to not leave people alone. We’ve been training to care for one another for a long time here. This is the time to be neighborly, maybe now double down on neighborliness. Look for the grace in the disruption. We have to pull together. Southern hospitality gives us a running start at this.”

At the end of our conversation, he finished with solid advice:

“The code is that you’ve offered something, so you take a little something.”

That should sustain me until the day when I can once again sit in a friend’s kitchen and have him say, “Let me cook you another egg.”

I will say please and thank you for seconds.