In the 1980s, some folks wrote off Ernie Mickler, author of “White Trash Cooking,” as a yayhoo curiosity. Others thought him one of the most brilliant Southern folklorists and photographers of the 20th century. But perhaps most importantly, Mickler left behind a testament to the fact that all Southerners — even those at the margins — have a right to claim their roots.

By Michael Adno | Photographs by Michael Adno, or courtesy of the University of Florida

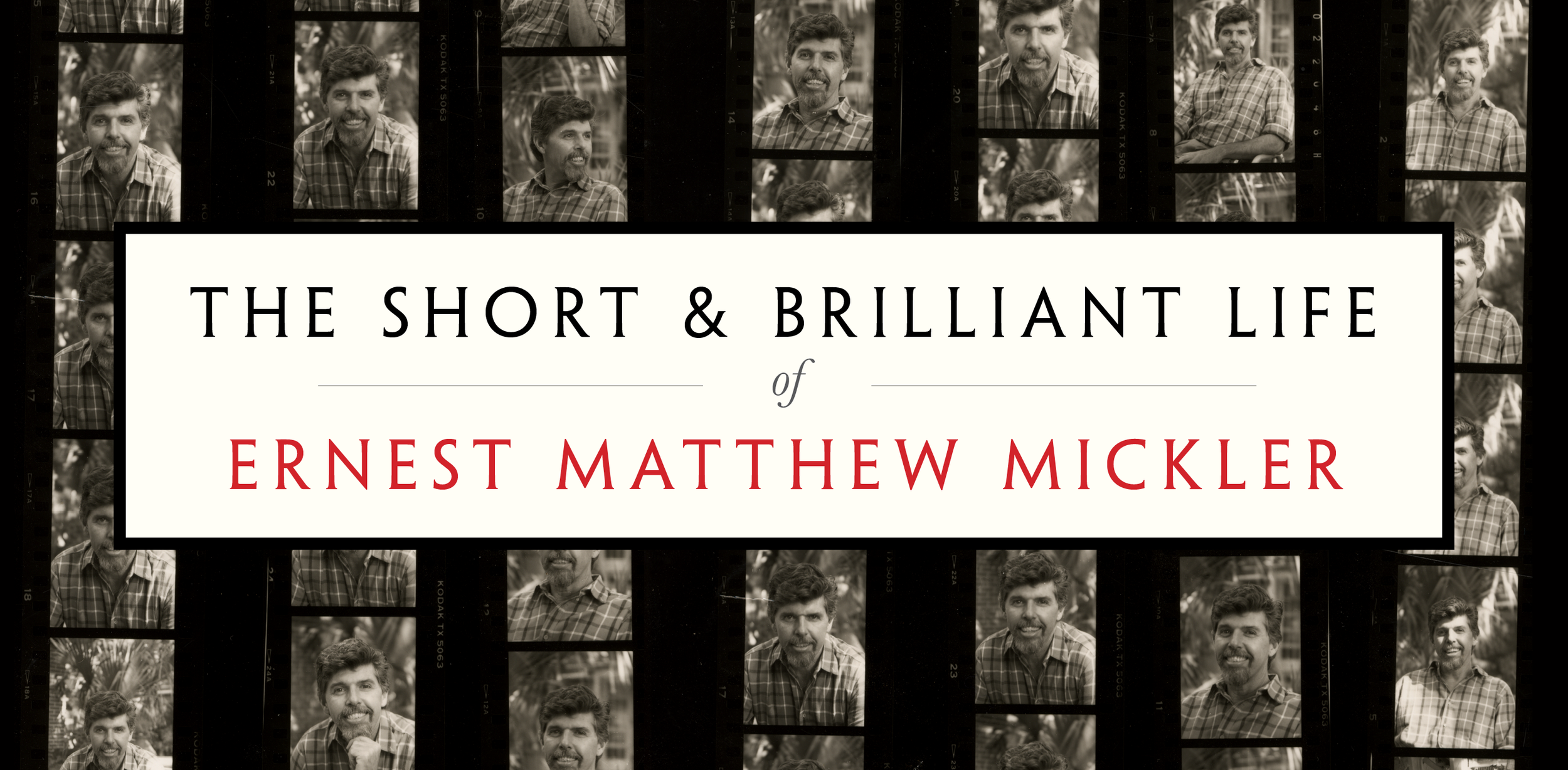

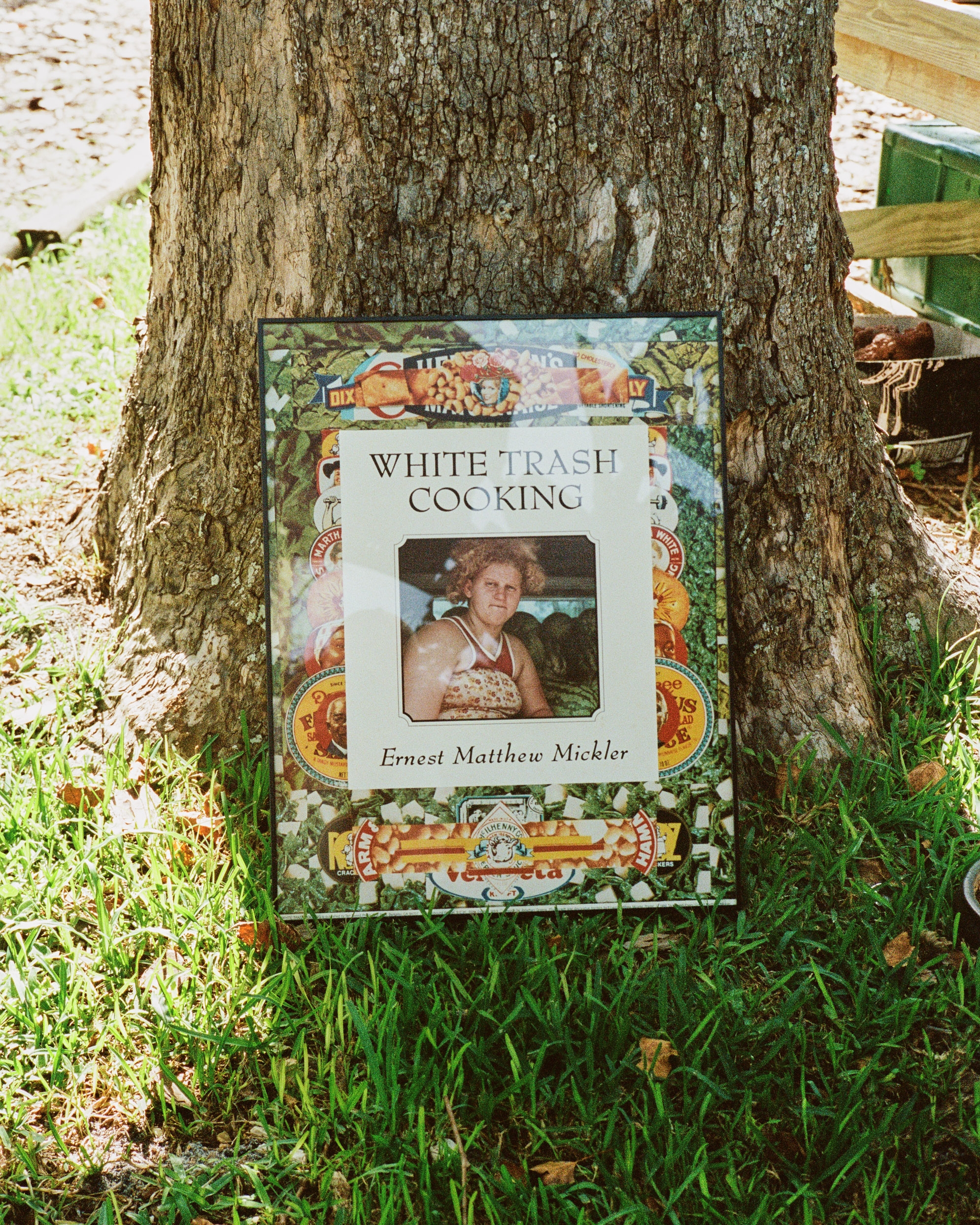

In spring of 1986, Ernest “Ernie” Matthew Mickler’s “White Trash Cooking” landed on bookshelves across America — a 160-page, spiral-bound anthology of Southern recipes, stories, and photographs.

Oddly enough, damned near everyone loved it. It was immediately revered by literary snobs, Southern aristocrats, Yankees, folklorists, down-home folk, and people on either side of the Mason-Dixon.

The book stirred a firestorm of publicity — partly serious, partly tongue-in-cheek — landing Ernie on “Late Night With David Letterman” and National Public Radio, in magazines like Vogue and People, and in a litany of newspapers. In The New York Times, critic Bryan Miller deemed “White Trash Cooking” the “most intriguing book of the 1986 spring cookbook season.” Even the grand dame of Southern literature, Harper Lee, claimed she had “never seen a sociological document of such beauty — the photographs alone are shattering.” She called the book “a beautiful testament to a stubborn people of proud and poignant heritage.”

“White Trash Cooking” was a staple on The New York Times Best Seller list for weeks as a gift for Southern kin, an eloquent medley of camp and honesty. It was Ernie’s reclamation of the South, as he knew it. And he knew it from a distinctly rural view. Ernie was born on August 23, 1940, in Palm Valley, Florida. Today, the TPC Sawgrass golf resort crowds Palm Valley from the north, but in Ernie’s youth, it was a backwoods haunt on a thumb of land along the Atlantic, about 10 miles south of Jacksonville Beach.

Ernest Mickler armed with a copy of "White Trash Cooking," a skillet, and his beguiling grin.

(Photo courtesy of the University of Florida.)

In “White Trash Cooking,” Ernie provided a thorough account of recipes and conventions many grew up with, some had forgotten, and others couldn’t imagine. Broiled Squirrel. Betty Sue's Sister-in-Law's Fried Eggplant. He built a simultaneously endearing and tempestuous catalog of archetypes — vestiges of the South, sets of beliefs and traditions that would otherwise dissolve into lore. Cool Whip, once prosaic, became profound in Ernie’s books.

No more than a month after “White Trash Cooking” hit bookstores, its original publisher, The Jargon Society, decided it couldn’t meet the demand and sold the rights to Ten Speed Press for $90,000 and a 15-percent royalties clause. Jargon had received 30,000 orders; it had printed only 5,000 copies. Ernie’s dear friend Calvin “Cal” Yeomans once said the publication of “White Trash Cooking” was “one fuck-up after another.”

Two years later, Ernie published a second book, “Sinkin’ Spells, Hot Flashes, Fits and Cravins.” It followed the first’s form, but went further. Its sections and stories were built around certain gatherings he grew up with in North Florida: hog-killings, cemetery cleanings, wakes. Ernie put the recipes in those contexts and colored them with prose that edged toward writers like Padgett Powell or Zora Neale Hurston in its ability to pin down regional dialect. Ernie himself said he was good at “writing cracker.” And, as in the first book, you could easily mistake Ernie’s photographs for William Eggleston’s or William Christenberry’s.

It’s safe to call “Sinkin’ Spells” a more mature, carefully crafted project — more idiosyncratic, regionally specific, and intimate. It was bound to do well after the warm reception of “White Trash Cooking.”

On November 14, 1988, “Sinkin’ Spells” arrived at bookstores across the country. The following day, as readers dove in, Ernie died at his home in Moccasin Branch, Florida, of AIDS. He was 48.

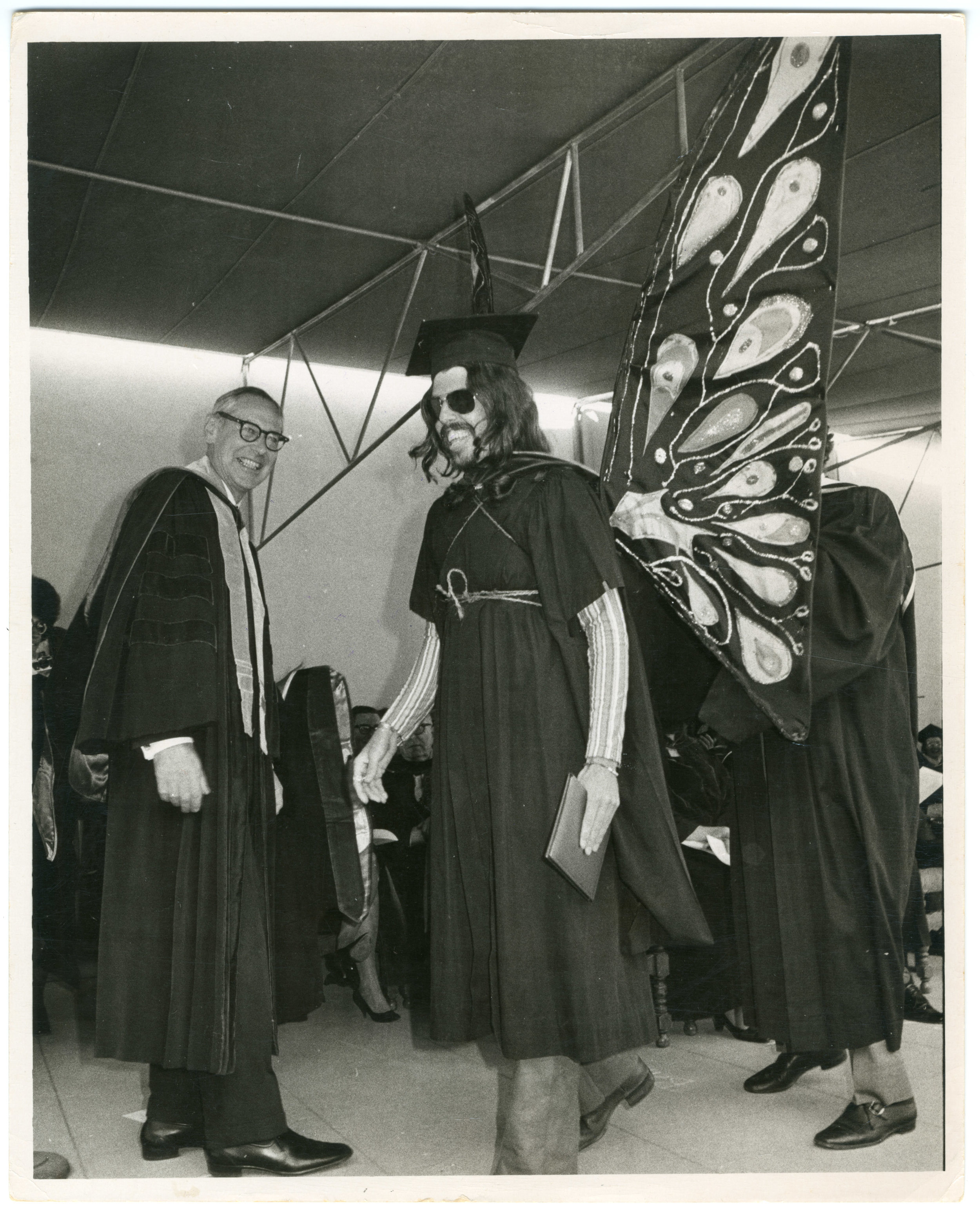

Sixteen years earlier, Ernie Mickler accepted his master of fine arts degree as one of only eight men graduating from Mills College, historically a school for women, in Oakland, California. On May 31, 1972, The San Francisco Chronicle devoted 10 inches of column space to a photograph of Ernie at the ceremony, under the headline, “The Art of Graduation.”

Mickler after receiving his M.F.A. diploma from Mills College. (Photograph by Larry Tiscornia for the San Francisco Chronicle, courtesy of the University of Florida)

Clad in aviator sunglasses, long hair, and a set of butterfly wings on his back, he traipsed out onto the stage — and the previously taciturn crowd hollered and laughed.

“It scared the shit out of me,” he later told a friend, “I just became this magnetic thing.” Helen “Petie” Pickette, one of his closest friends, told me, “I used to say he glows in the dark, and he may have.”

I visited Pickette at the apex of summer in Jacksonville Beach. Cicadas whirred and the temperature spiked as my vehicle snaked toward her house on a Saturday morning. When I knocked, I heard music, a voice with a texture akin to Townes Van Zandt’s, spilling onto the porch. When Pickette opened the door, she looked me up and down. She wore a burgundy T-shirt, thin-rimmed glasses, and an ear-to-ear grin.

“Mike, you look like one of mine,” she said. “Get in here!”

The seemingly familiar voice I heard from the porch was still playing, and it nagged at me. Pickette told me it belonged to Ernie. That’s when I noticed an image of Ernie and Pickette straddling a guitar, framed on the wall, next to an image of Joan Baez. Half of the songs playing, she told me, were tracks Ernie recorded in New Orleans, and the other half belonged to their duo, Ernie and Petie. Ernie sang, and Pickette played guitar. In April 1962, when Ernie was 21 and Pickette merely 18, their single, “Our Love,” climbed to the No. 2 spot on the sales chart — at least the chart at Abe Livert Records in Jacksonville. The No. 1 track was Elvis Presley’s “Good Luck Charm.”

“Ernie had talent from the top of his head down to his feet,” Pickette said.

They played a gig with Roy Orbison, met Patsy Cline, ran around with Skeeter Davis and Ralph Emery, and even bumped Brenda Lee off a live spot during Emery’s broadcast from the Country Music Conference. Then, during a studio session, their manager got under Ernie’s skin.

“He started cussing — went into a rant,” Pickette remembered.

And their manager just told them, “That’s it. Go home.”

Ernie and Petie in 1962. (Photo courtesy of Helen Pickette)

“We told people Ernie wanted to go to college, which was true. It just so happened to coincide that Ernie wanted to go to school when we got thrown out,” Pickette said, laughing. When her smile ran out, she said, “I can’t remember the last time I played my guitar.” Her eyes moved toward a Guild acoustic near the front door. “It reminds me that he’s gone.”

After Ernie and Petie’s foray into country music, Ernie moved to Atlantic Beach. There, he met Memphis Wood, director of Jacksonville University’s art department. Memphis could see a flare in Ernie, and she encouraged him to enroll.

"I'll be your counselor,” she urged, “I can get you on the right line.” In fact, the wings he wore on graduation day at Mills College were dedicated to Memphis.

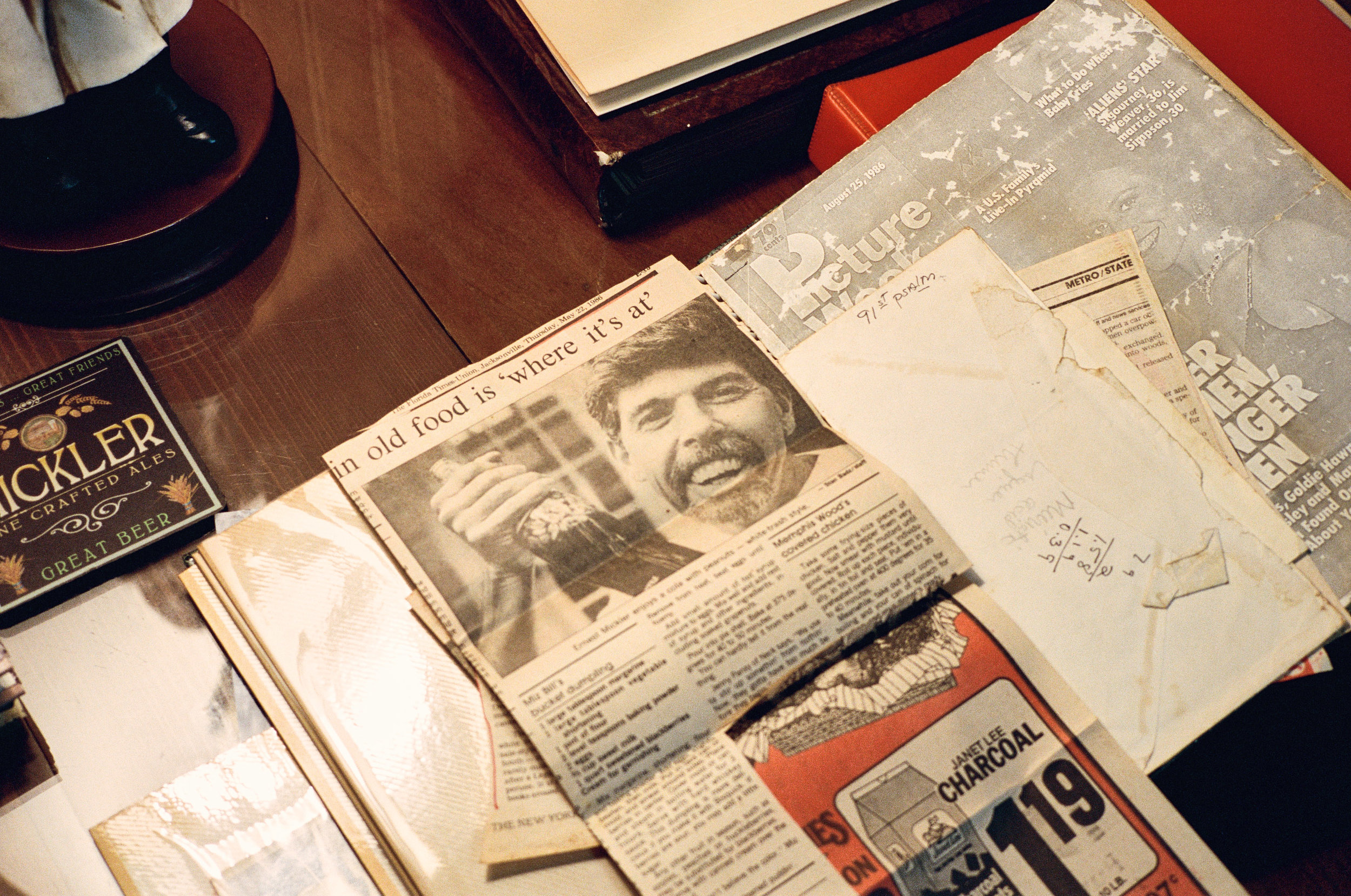

Pickette and I moved to a table in the kitchen strewn with Ernie Mickler ephemera. She showed me photos of Ernie as a boy with that same infectious smile, pictures of his family, and the old Palm Valley — Ernie’s Palm Valley. Poring over images from their trips together — New Orleans, Mexico, California — she remembered how Ernie’s charisma was inescapable, no matter the locale.

“He’d come into a room, and every head would turn,” she said.

Two days later, I picked Pickette up early, and we drove down A1A to Palm Valley. We hooked west onto Solano Road, through a gated community, past retention ponds and manicured golf greens, to the home of Ernie’s cousin, Faye Farace. Farace pulled out several albums and showed us photographs of Ernie in shows, his guitar draped around his neck. The two women shared quips about the people of Palm Valley 60 years ago, before golf courses enveloped the place, and they started calling the area Ponte Vedra Beach.

Back then, “They didn’t call the law,” Pickette said. “They handled things themselves.”

Shotgun shacks, fish camps, and moonshine stills set back in the sticks made up the quiet community.

“Of course, everybody knew everybody else’s business,” Farace said.

Culling together a sense of Florida today and back then while retracing Mickler’s footsteps. (Photographs by Michael Adno)

Stretching back to 1759, a land grant bears the name John Michler. As reported by Patricia Mickler, who penned an extensive family history, Jacob Mickler married Manuela de Ortega in 1831. And all across North Florida, you can find mentions of the Mickler family whose roots run deep down here. Pushing down Mickler’s Cutoff — the two-lane pavement that cuts through Palm Valley — Pickette mentioned how Ernie’s taste in food reflected his family’s Minorcan heritage. He adored pilau and fish and grits.

At the terminus of Roscoe Boulevard, where a bridge crosses the Intracoastal Waterway — or, as locals call it, “the canal” — we pulled into a gravel lot leading up to a restaurant on the water. This used to be Papa George’s Fish Camp. More importantly, though, this land was also where Ernie grew up.

Across the canal, we could see docks marching off into the haze of an approaching squall. Pickette tried to place exactly where Ernie’s house was.

“They had a really fabulous oak tree in their yard,” she said, but all traces of that were long gone. When Ernie was 6, his father died. Left alone, Ernie’s mother, Edna Rae, opened up a general store and gas station here. Gossip made its way through Edna Rae’s promptly, inevitably becoming fodder for Ernie’s stories.

Back in the car, we crept down a two-track plastered with “No Trespassing” signs.

“Yeah, the one that says, ‘Keep out.’ Go down there,” Pickette told me. We reached a small compound of homes on a stunning finger of land pushing out into a nexus of creeks and cordgrass. At the end of the road, a sable-palm cabin stood — a cypress addition tacked on, and a sliver of a screened porch out front. To my surprise, Pickette knew the old-timer who came out to greet us with his cattle dog and invited us to walk around the property — crystal clear ponds, wild grapes, and cypress trees sandwiched between the tidal creeks and untamed pine scrub. Leaned against a tawny pine, an oversized grave marker in the shape of a tombstone read: Here lies Palm Valley, Choked to death on a golf ball.

Soon enough, I realized this wasn’t accidental. Pickette brought me down this road to see the Palm Valley of Ernie’s youth. It was a place, as he wrote, “where you never failed to say, ‘yes, ma’am’ and ‘no, sir,’ never sat on a made-up bed (or put your hat on it), never opened someone else’s icebox, never left food on your plate, never left the table without permission, and never forgot to say ‘thank you’ for the teeniest favor. That’s the way the ones before us were raised, and that’s the way they raised us in the South.”

Oddly enough, the idea for “White Trash Cooking” first emerged in 1972 in a lean-to near Washington, California, a tiny town on the Yuba River between the Plumas and Humboldt-Toiyabe national forests in the foothills of the Sierras.

On 50 acres that belonged to Ernie’s friend Laura, the two stayed in a little tin shack attached to a barn. Laura, a high-up in health education from Oakland, supported Ernie while he lived in San Francisco, and she thought he’d be handy in making the shack a home. She’d send Ernie out to local flea markets — where he was selling his own wares — so he could spiff up the place. While rigging it up, the spark happened. Laura pointed out an ability Ernie had. There was a simple elegance about everything he did, without a need for much money to live pleasantly. As Ernie would explain time and again, to be “White Trash” was something to be proud of. In the introduction to White Trash Cooking, Ernie laid out a distinction between uppercase “White Trash” and lowercase “white trash,” claiming that “Manners and pride separate the two.” To be poor, Southern, and White Trash was anything but shameful.

In October 1988, just a few weeks before he died, Ernie was interviewed by his friend Cal Yeomans. Ernie had rented a house in Crescent Beach to be near the Atlantic one last time, and there, he talked to Cal about the book’s genesis.

“We got stoned out of our minds one night, and honey, we were seeing monkeys on the wall almost,” Ernie said. “I can't take full credit for it; we all came up with the idea of doing a guide to the art of white-trash cooking on video.” From there, Ernie labeled a folder and “started putting stuff in it from paper sacks — this, that, and the other.” He took off from San Francisco en route to Jacksonville, where he had lined up a teaching job. But on his way through New Orleans in 1972, he remembered, “Halfway down St. Charles, I said, ‘Shit, I don't need to go any further. This is it.’”

While living in New Orleans, Ernie met William “Bill” Fagaly, the former chief curator at the New Orleans Museum of Art. They took to each other, and part of “White Trash Cooking” was put together with Fagaly at Ernie’s side. Ernie didn’t drive, but he didn’t need to, Pickette says, “because everyone he met was willing to take him where he wanted to go.” Fagaly was a staunch supporter of Ernie’s and remained so even after their relationship fell apart. Then, Ernie met Robert Somerlott , and they set off on the road together. Ernie ultimately dedicated “WTC” to “Robert.”

In 1976, Ernie ended up in San Miguel de Allende in Mexico. There, he literally ran into the author Edward Swift turning a corner. With 1,000 recipes brimming out of sacks and shoe boxes, he explained the idea to Swift — a Texan — and he agreed to help Ernie type it up and draft the introduction. The final introduction was their collaboration. Ernie said of Ed’s role in the book, “That was a gift from God, and I'll never forget it.”

Over four years in San Miguel, Ernie honed the material. Then, when his relationship with Somerlott fizzled, Ernie didn’t want to return home just yet, and he settled on Key West, Florida, as his next home. In 1980, just as Key West was turning from a sleepy, war-time remnant into a destination resort, Ernie arrived. He began cooking for all-male guesthouses and drank the place in. As Pickette told me, “If it weren’t for Key West, ‘WTC’ probably never would have been published.”

Mickler drawing at home in Key West, Florida. (Photo courtesy of the University of Florida)

While in Key West, Ernie met Anthony “Kit” Woolcott, an English entrepreneur with a foothold in the publishing world. Woolcott asked Ernie to make six copies of his manuscript, and he offered to send it around. Publishers in the Northeast immediately fell head over heels for the thing. The title, though, just plain terrified many of them. Ernie received a letter from David Godine, the head of Godine Publishing in Boston, that said he could never publish such a title, because it would offend three-quarters of the United States. After Jargon Press published the book, it sent an advertisement to The New Yorker, but the magazine sent the check and materials back — claiming it would offend the magazine’s readership. Of that kernel, Roy Blount Jr. mused, “That just goes to show how much The New Yorker knows about anything involving Gravy.”

Nonetheless, Ernie’s tenacity carried the thing to print and into people’s homes. In a letter to Doubleday, Woolcott wrote, “It has been culled from a great knowledge of Southern cooking and is to a certain extent a historical statement of the development of American cuisine in the Deep South.”

Then, Woolcott’s partner — a Southerner, Joe Bailey — suggested publishers in New York might be unable to see the promise of “WTC,” so they sent the book to the Jargon Society, a rather obscure literary press in North Carolina, led by the poet and self-described “artisto-dixie-queer,” Jonathan Williams. Tom Meyer, Jargon’s executive director, recounted the story to me.

“Kit asked as a favor us to look at a cookbook a young ‘caterer’ he knew in Key West had written,” Meyer said. “Kit sent the typescript, which sat on the desk for a couple months. Jonathan asked me to look it over before he returned it, assuming it wasn’t anything our press would be interested in. I sat down, read it, and told Jonathan, ‘This is fantastic — all the way through, the recipes, the presentation, the voice.’” And he added, “‘WTC’ was the only manuscript I recommended Jonathan publish I’m proud to say. The rest is history.”

Jargon’s Williams called the Oasis guesthouse where Ernie worked. Ernie was staying down the block, and when word reached him, he ran over like a bat out of hell to take the call. Phone to his ear, Ernie listened: “My name is Jonathan Williams with Jargon. Joe gave me your book, and we want to print it.” As Ernie recalled, “I almost fell off the end of the telephone.”

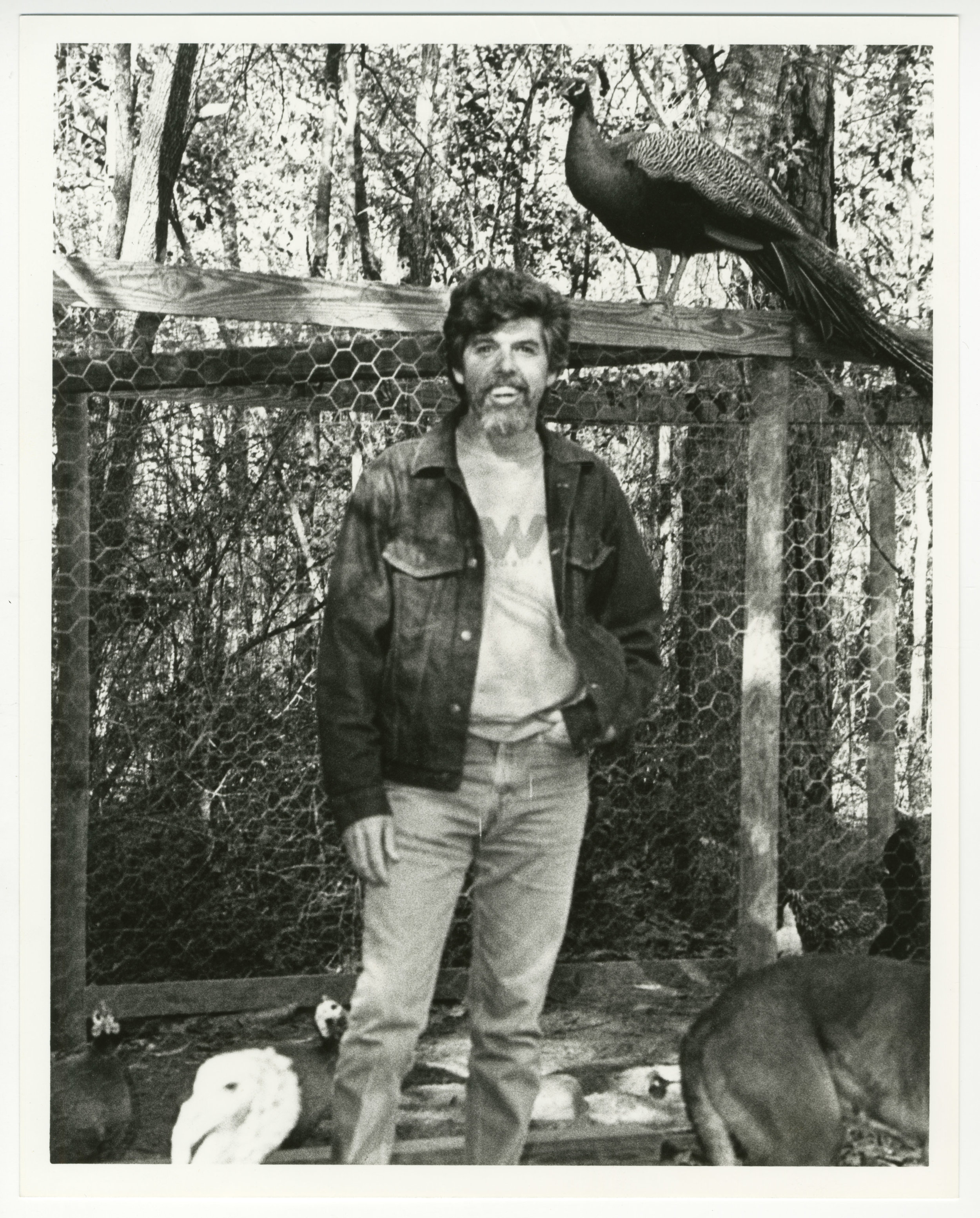

Mickler while working on his second title, "Sinkin' Spells, Hot Flashes, Fits and Cravins." (Photo courtesy of the University of Florida)

After Jargon took the book on, they began raising the money to print the thing. But more than a year later, Woolcott grew frustrated with Jargon’s glacial process, so he bought two tickets to Winston-Salem to crash the publisher’s next board meeting. Mickler and Woolcott arrived as Jargon was hosting an art opening. Ernie felt out of place among the art snobs. But soon enough, someone screamed at Ernie, “I’ve seen you in drag!” And in a moment, the purported pretension fell away.

At the meeting the next day, a portion of Jargon’s board members sat around the table with Ernie and Woolcott. After a bit of circumspection, they agreed to table the book for another year due to a lack of money, but Woolcott stood up and said, “If you people don’t print this book, I’m going to print it myself.” Woolcott offered $2,000 and typesetting right there. Then, Philip Haines — maybe the book’s most ardent and unsung supporter — put down $5,000, followed by $10,000 from Don Anderson, an oil magnate. That day, $25,000 came to the fore, and ‘WTC’ finally reached escape velocity.

On February 19, 1986, Woolcott and a group of friends hosted a release party for “WTC” at the Oasis. The culmination of 14 years of Ernie’s work had arrived in an Eden-esque garden off Key West’s Fleming Street. From there, he took off on tour, touting the book at conventions and bookstores from Ocala to Atlanta. In New Orleans, at the American Book Sellers Show, Ernie was promoting the book with Jargon. Walking around the booths, he recognized David Godine, introduced himself, and presented him with the Times review. Ernie waited for Godine to read through it. When Godine looked up, he admitted, “Well, you know, that was just a bad mistake I made.”

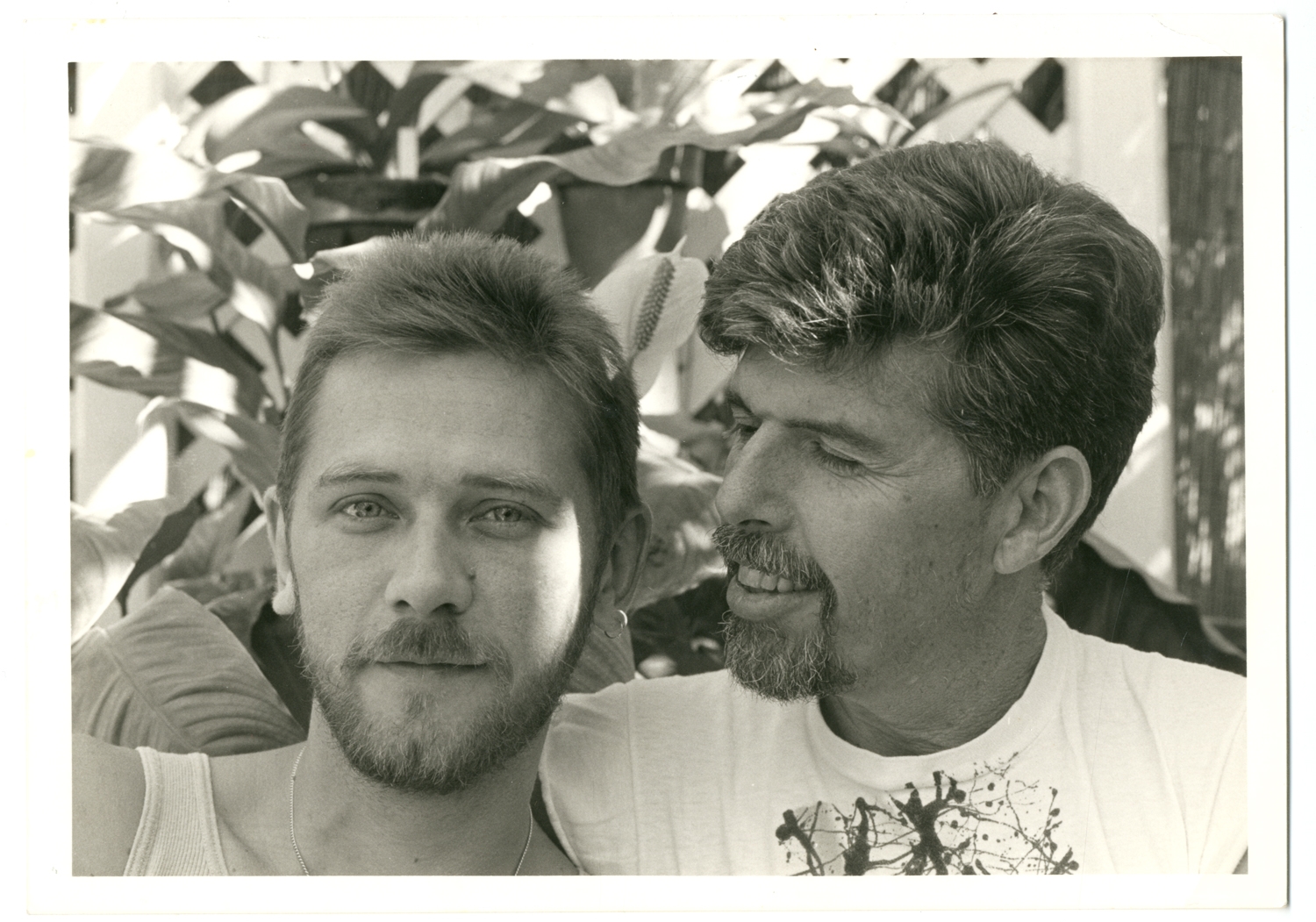

Soon enough, Ernie’s grin was strewn across magazines and newspapers. Food sections clamored to cover the book, photography outlets too. Following the book’s release, Ernie and his partner Gary Dale Jolley moved from Key West to St. Augustine into a little shoebox of an apartment. They were looking to buy something more comfortable, but they were still living on piddling amounts. The royalties from Jargon hadn’t shown up yet. And in December 1986, following a People magazine article that cited $45,000 in royalties, the Ledbetter family of Alabama filed a lawsuit against Ernie, because the front cover featured a photograph of their daughter. On photo trips, Ernie would ask everyone for their permission, explaining the book’s purpose. Of course, nothing was on paper — just an agreement incised in emulsion.

Soon enough, the Junior League of Charleston followed suit, claiming that 23 recipes were plagiarized. And in the end, it was a delicate dance that cost Ernie immensely. When a royalties check came in from Ten Speed at the end of 1986, it totaled $180,000. Out of Ernie’s half, $70,000 went toward legal fees and settlements. He remembered $50,000 going to the Ledbetters.

After Ernie appeared on a number of national television shows, he said, “The only thing I didn't like was they kind of made me feel like I was a buffoon. They just had me up there on a stick.” He told Cal Yeomans he would happily return to television if the hosts would speak to him intelligently. But if it were another horse-and-pony show, “I ain’t going through that again.”

Maybe the most evident example was Ernie’s appearance on David Letterman to cook chicken feet and rice. A trash-can erupted with roiling grease, and Ernie presented the dish to Letterman, who found it laughable — asking if chicken feet were just pure gristle, then refusing to eat it. Such incidents led to Yeomans’ characterization of the book’s rollout as “one fuck-up after another.”

None of those incidents, however, kept Americans from embracing Ernie Mickler. Some thought him a prodigious folklorist, and others thought him a roadside curiosity, but the friends, stories, and experiences Mickler collected while assembling the book is more than most collect in a lifetime.

He had also collected more confidence in the value of his work. And Mickler turned eagerly to writing his second title, “Sinkin’ Spells, Hot Flashes, Fits and Cravins”

Ernie and Gary found a modern house set on 1 ½ acres in Moccasin Branch, about 10 miles west of Crescent Beach. When the offer was accepted, Ernie persuaded Ten Speed to mortgage the house with his royalties as collateral. And there, Ernie worked like mad to put together the next book, all the while hemming the place in with his charm, naturally.

He said of their Moccasin Branch home, "I don't think I've ever lived in a place that's just so gentle on your head."

Ernie worked with graphic designer Jonathan Greene on both books. Greene told me he sensed an undeniable urgency in Mickler’s voice on their second go-round.

“I had no idea why [at the time],” Greene said, “but, of course, he wanted to see the book before dying.”

When Ernie first set off to make photographs for “WTC,” he went to see Pickette, who then worked at Brandon’s Camera in Jacksonville. She set him up with a rangefinder, showing him the nuts and bolts, and then he took off. Later, when magazines hailed Ernie as a Southern master of photography, Pickette said, she wanted to scream, “The man can’t load the film!” But she added: “As long as he could be told how to point something, he could compose a picture.”

In his photographs, there’s an affinity for his subjects that can’t be learned, only lived. While he wasn’t a pedigreed photographer, he had a natural inclination, and the rangefinder suited him. His photographs’ likeness to those of Eggleston and Christenberry is uncanny, and to those of Walker Evans maybe more so.

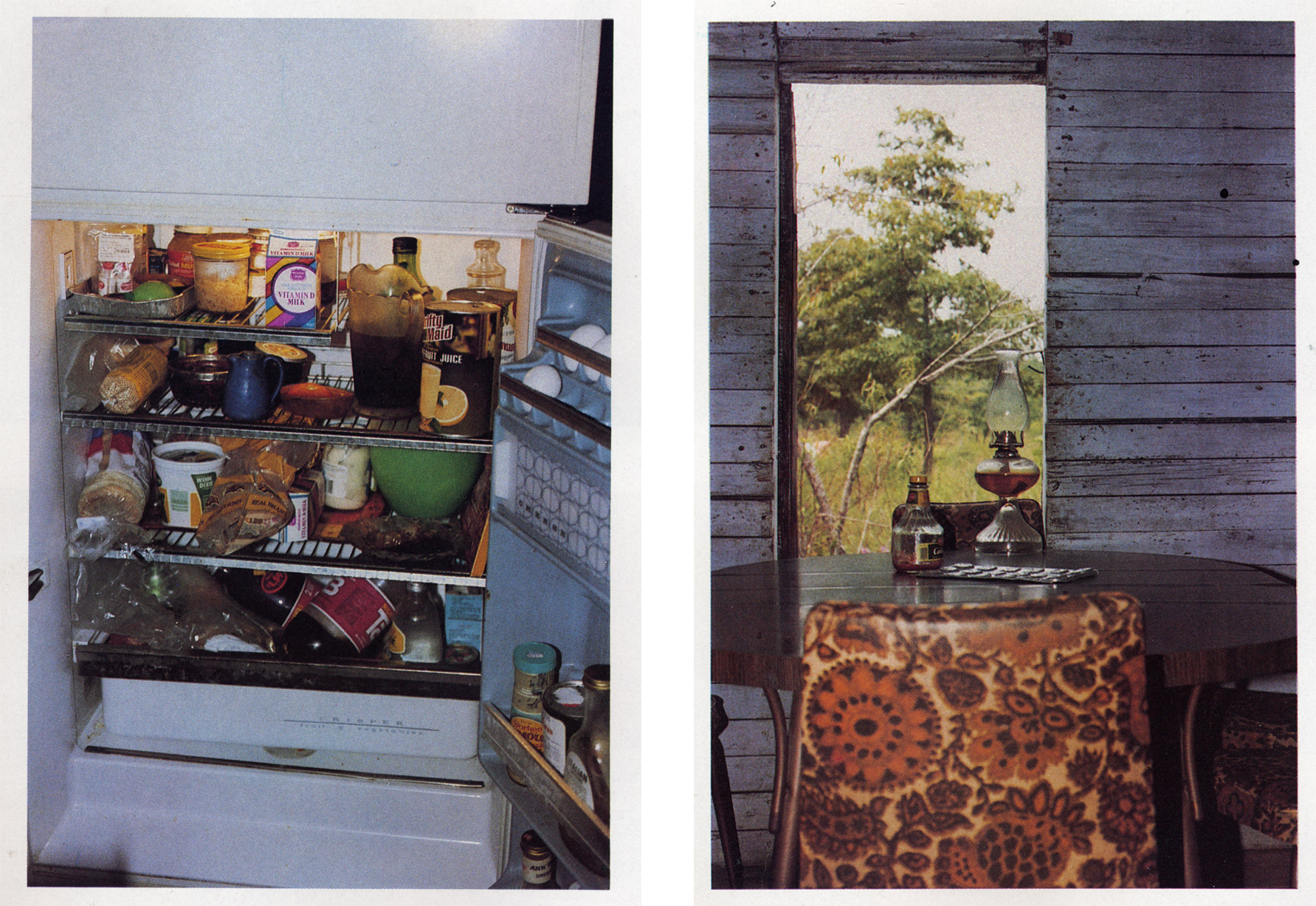

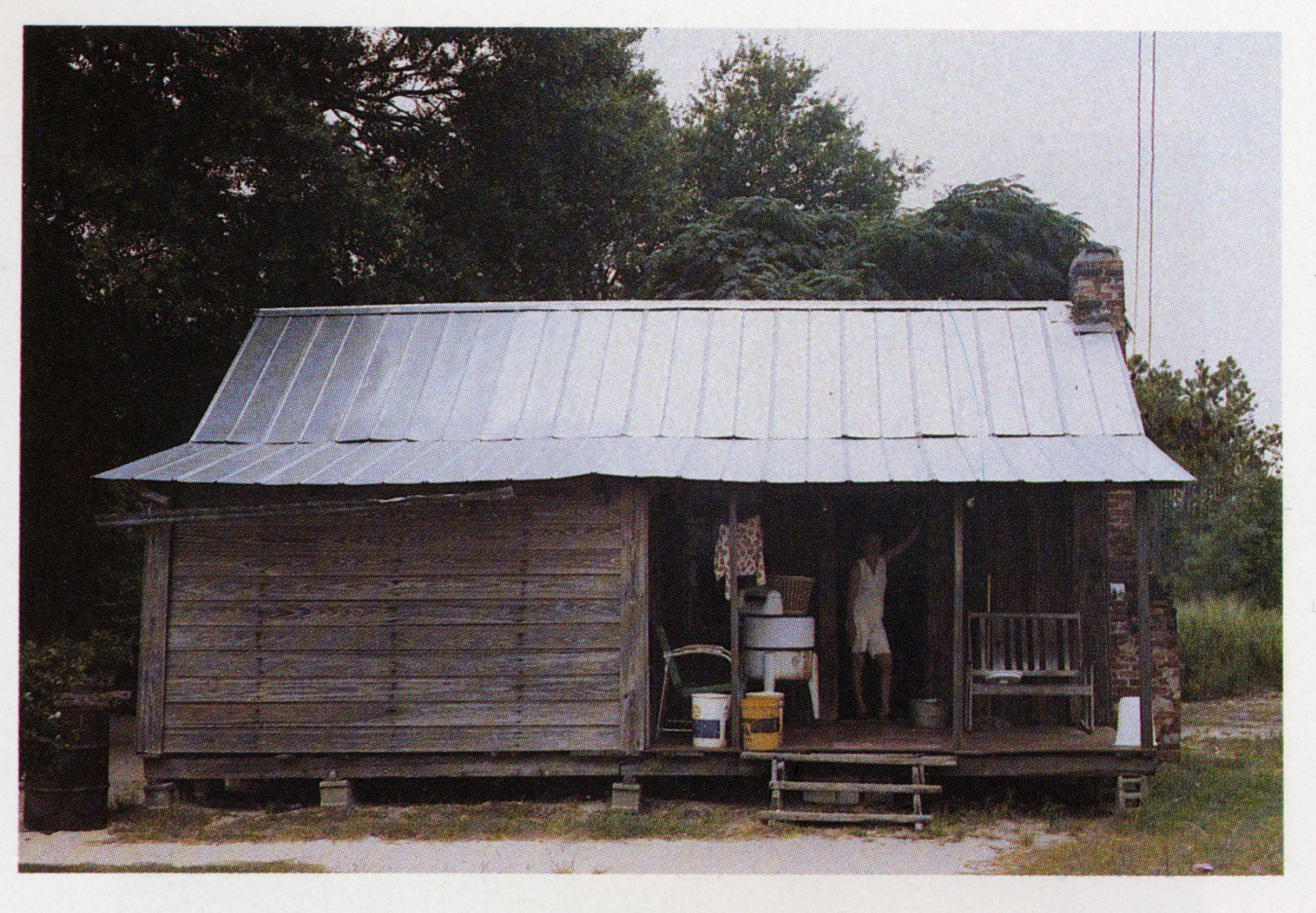

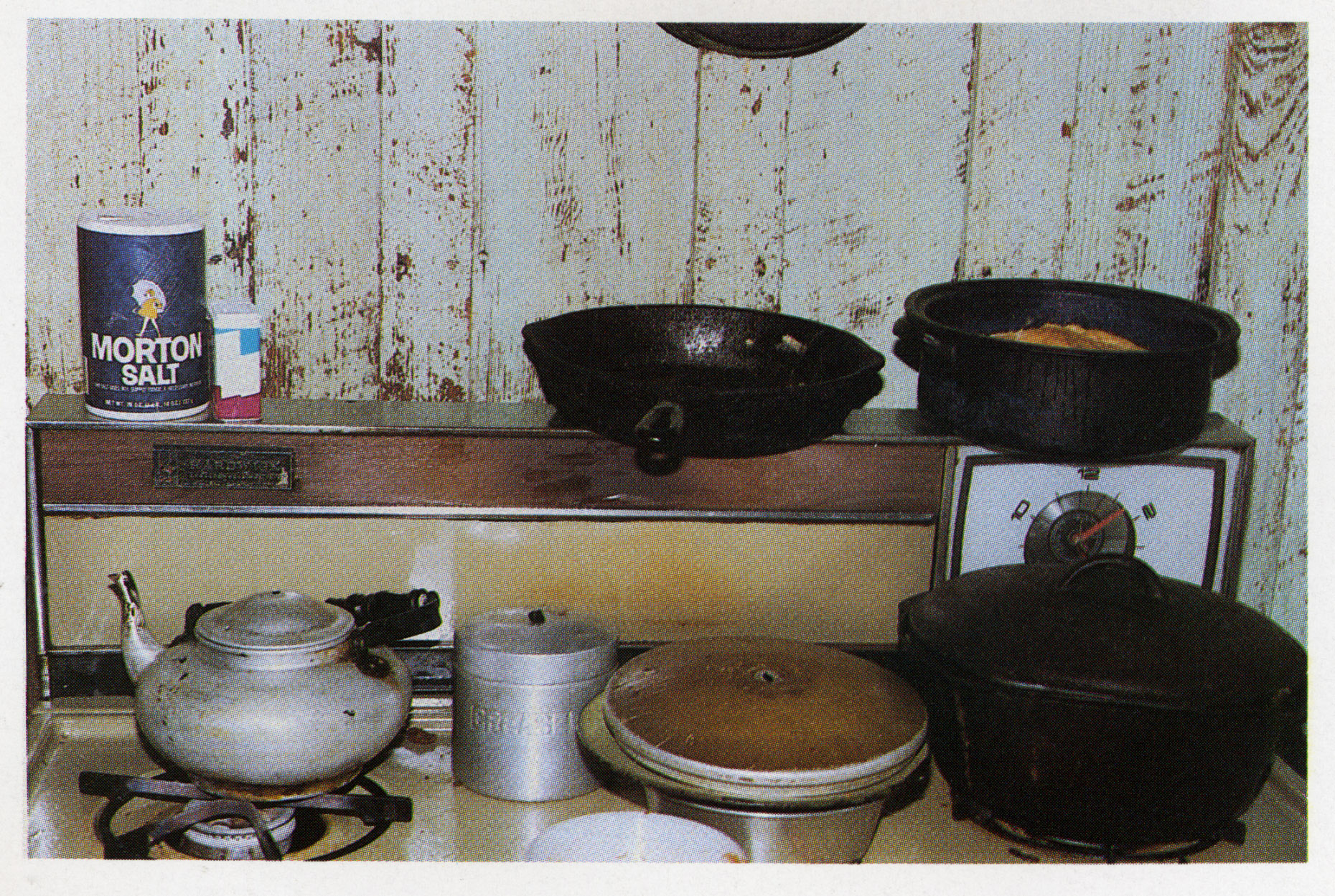

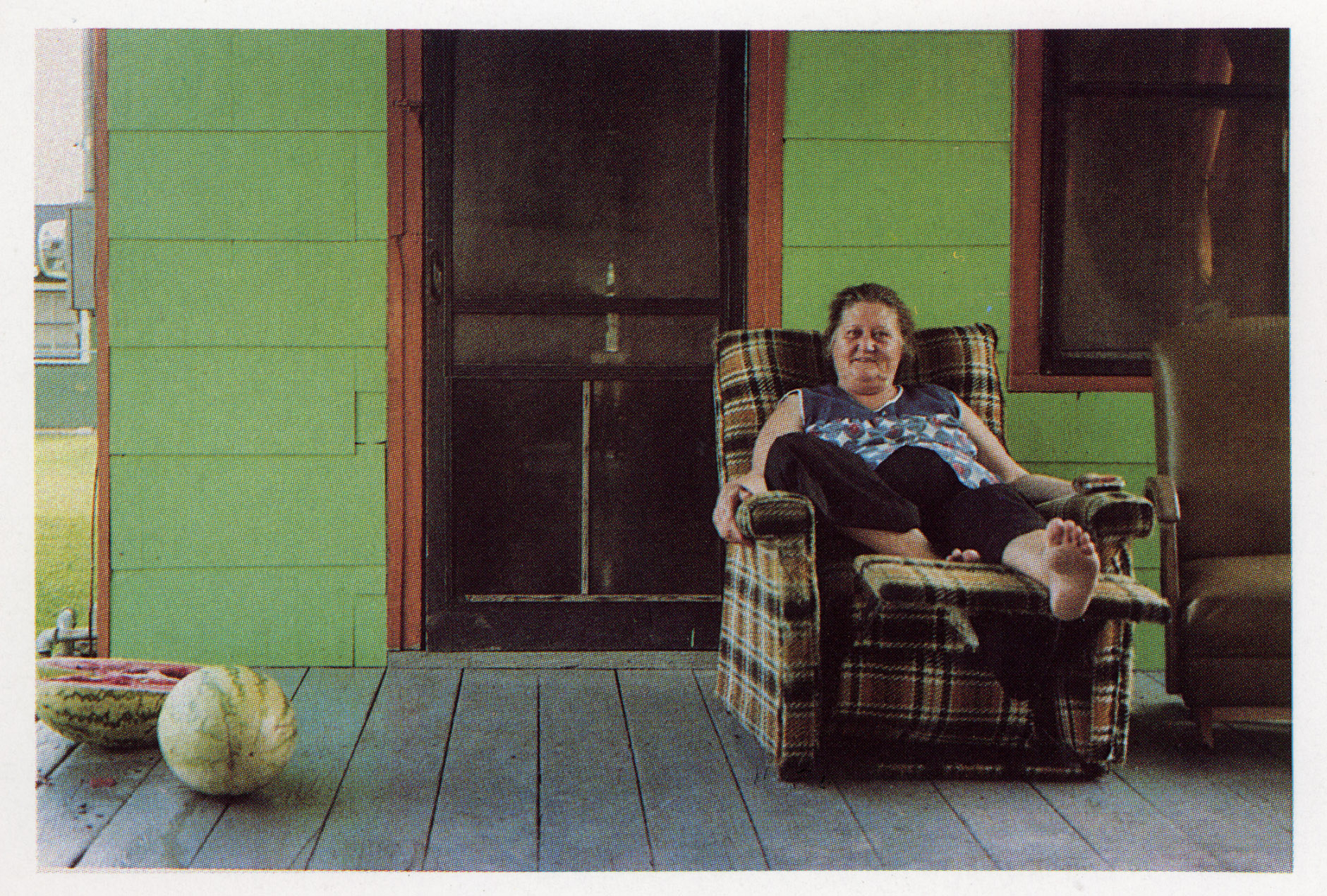

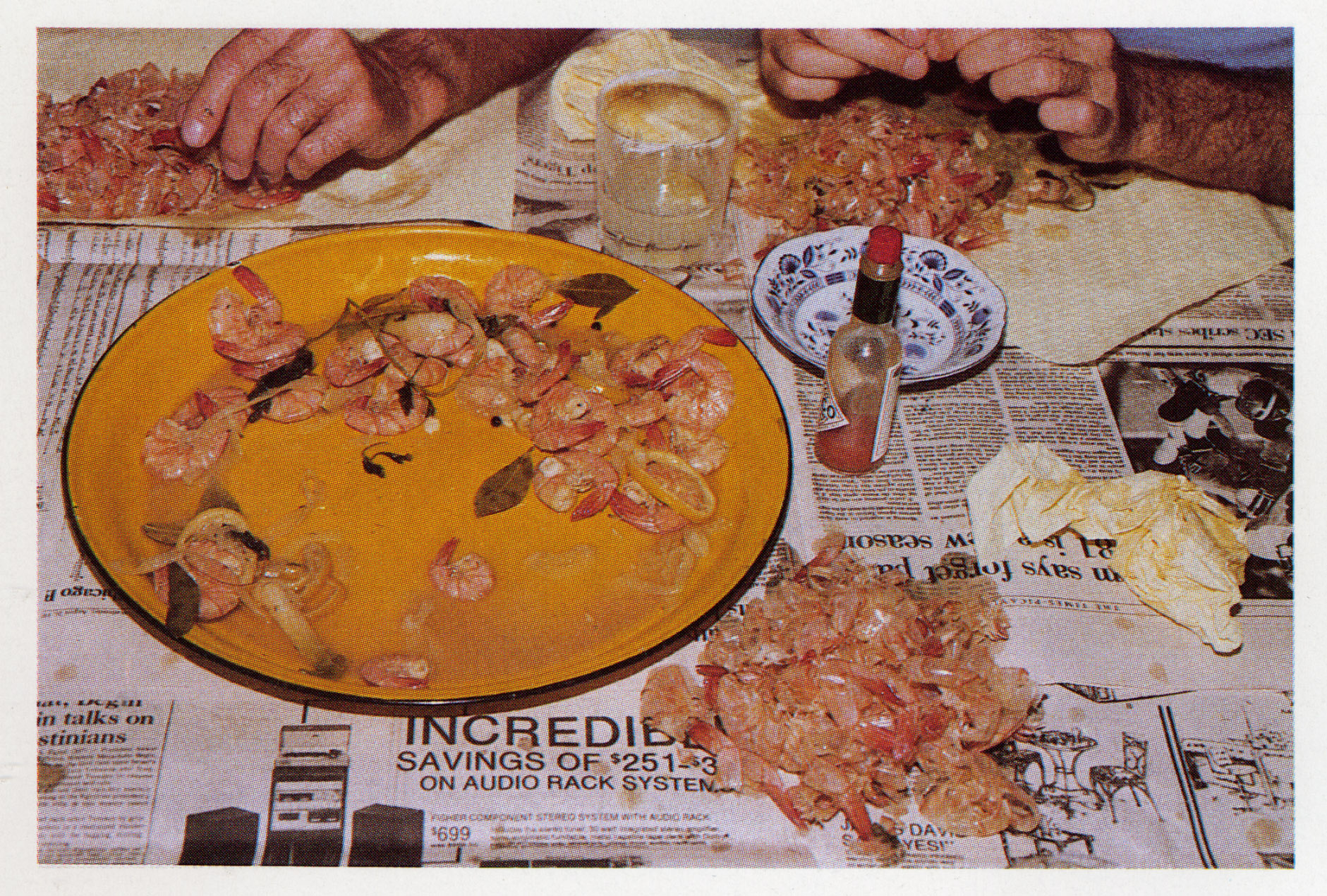

Photographs included in "White Trash Cooking" by Ernest Mickler. (Photos courtesy of the Mickler estate)

Richard McCabe, curator of photography at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, told me he clearly saw Walker Evans in Mickler’s work, and talked about how his churches and interiors were reminiscent of Evans and writer James Agee’s seminal vignette of Hale County, Alabama, “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.” (Playing off the same comparison, Southern Foodways Alliance Director John T. Edge in 2006 penned a piece about Ernie titled “Let Us Now Praise Famous Cooks” for Oxford American, and that piece was adapted for the foreword for the 25th anniversary edition of “WTC.”)

“When you think about Eggleston or Christenberry, you think about sense of place and culture,” McCabe told me. “Well, one way to define a culture is by the food they eat.” McCabe said that as Christenberry used photographs of the same building, repeated over time, to register a sense of place, Ernie used food. He argued his case well, demonstrating how Ernie’s photographs of cooking pans, signage, and buildings all point back toward the work of Eggleston, Christenberry, and Evans.

“In a way, he was more of a folklorist with a camera,” McCabe said. Ernie’s compositions, he said, shift between Eggleston’s dynamism to Christenberry and Evans’s deadpan approach. While Ernie’s work doesn’t lie under the weight of an era of social documentary’s scrutiny, as Evans and Agee’s book does, it’s become embedded in the narrative of the South, regardless of its notoriety. Ernie, like Christenberry or Eggleston, is one of the few Southerners who have represented the region with such acuity. And in 1986, he attracted the attention of prominent collectors. One wrote to him to let him know his work would be in good company next to the Christenberry and Eggleston prints in his home.

It didn’t matter Ernie had no idea how to use a camera; it mattered that he shot what he knew best.

The intimacy in his photographs spills off the page into the stories and then the recipes, and it all amounts to something home-grown and poignant. And undeniably, like with the aforementioned artists, there are strong connections to photographers like Clarence John Laughlin, William Ferris, and Fonville Winans — who all documented the Delta region (Winans actually began a project akin to Ernie’s in the 1950s in Louisiana).

But maybe the most uplifting characteristic of Ernie’s photography, McCabe said, is his understanding of his own region and its people.

“He didn’t hate it,” McCabe said. “He wasn’t ashamed of it. It empowered him. People either reject or embrace their upbringing, but he elevated it.”

Both books were ahead of their time, and both books still hold a strange, unmistakable relevance today as anthropological records of the South. And with each passing day, they accrue meanings. Who knows what additional meanings escape our notice today because we lost the books’ maker, Ernie Mickler, entirely too early?

In St. Augustine this past summer, I parked in Lincolnville, where Ernie lived, swung up a narrow, brick-paved block, cut through an arch into a courtyard, then climbed a tiled staircase up to the St. Augustine Historical Society. The charm swelled as I passed through a glass door and met Charles Tingley, a senior researcher as loquacious as his bearing on the region’s history is deep and an encyclopedic storyteller.

He ushered me into a set of study rooms and recounted his memory of meeting Ernie at a book signing in St. Augustine. (He also remembered that event’s sugar cookies made with Tabasco sauce.) He told me stories about how Ernie’s work was treated after his death, how “Sinkin’ Spells” was retitled “White Trash Cooking II” in an effort to sell more copies, and how family members penned subsequent books building off the “WTC” brand.

Looking down, Tingley paused, then, in a softer register, told me, “It was such a shame the Ernie died so young, because he was such a great folklorist.”

A collection of albums, press, and ephemera that Helen "Petie" Pickette has amassed over the past 30 years. (Photograph by Michael Adno)

Fortunately, Ernie Mickler’s work lives and breathes in the annals of the University of Florida’s Special Area Studies Collection in Gainesville, among alongside the papers of Zora Neale Hurston, Stetson Kennedy, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and countless other pillars of Florida’s literary and artistic heritage. Fifteen metal-edged boxes ultimately stake out Ernie’s life through correspondence, photographs, and manuscripts — many unseen.

On the second floor of the Special Area Studies’ library, I asked Florence “Flo” Turcotte, UF’s literary manuscripts curator, what a collection like Ernie’s offered students.

“You want people to go to the archive and understand something about themselves,” she replied. “I think people are looking for connections to the past to help them move forward.” And Ernie’s archive, she said, might be particularly rich in that regard.

Turcotte told me she always goes to the correspondence in a collection first, because it’s a window into people’s lives that doesn’t contend with the weight of posterity.

“It’s just plain communication,” she said.

“There’s some things in there that are a surprise,” Turcotte said. She explained how collections are often “sanitized” in order to mold the legacy that’s left behind. But Ernie’s, she said, is “really pure.” Anyone can pore over his will, literary contracts, deeds, W-2s, love letters, or manuscripts.

After spending so much time with his papers, it gave me a deeper, more genuine understanding of Ernie Mickler; it was the covalent bond for this story ultimately.

Ernie’s papers allow a researcher to see how a book comes together, the process, hardships, and rewards, but it also serves as testament to his vulnerability, his resilience, and ultimately his grace — the qualities that carried him so far.

After I passed through a torrential downpour on my way east from Gainesville, out State Road 26 toward Melrose, the sky held back finally as I hit the edge of the city. I passed clearcuts next to conservation easements, Trump banners, and vestiges of “old-timey” Florida — things Ernie might have photographed. In Melrose, I hooked left on State Road 21 north to Keystone Heights to meet with the writer Andrew Holleran, who was a friend of Ernie’s — and whose book “Ground Zero,” published in 1988, chronicled the earliest years of the AIDS crisis.

The air hung heavy as I stepped out of my car at Johnny’s Barbecue — the way it does after morning thunderstorms in this fecund corridor of the state. Inside, Holleran sat on a bench, and when he looked up, his smile seemed to broaden from his eyes down to his chest. We sat down in a red Formica booth against the window. Holleran had the special: smoked chicken, lima beans, and coleslaw. I had David’s Deal, a jumbo pulled-pork sandwich with baked beans.

Holleran’s family moved to Keystone in 1961, shortly before he took off to college at Harvard University.

“Cal [Yeomans] and Ernie were to me the real Floridians, and then there was the rest of us, the late arrivals,” Holleran said. “Both Ernie and Cal were small-town aristocrats. They had the same values. They knew they were from a state that everybody made fun of, yet they loved Florida, and they took it seriously. They had a kind of anthropological historian’s appreciation for the outsider, and [yet] they were part of it. They had this double vision about Florida. That’s what made them fascinating. We were all doing the same thing: We all had to leave Florida to be gay, but we never entirely severed the relationship, and then we ended up coming back.”

Ernie told Yeomans that when he came out to his three brothers, “They were polite at the very best, but they didn't come see me, I didn't go see them. They wanted nothing to do with me ’cause I was queer. Simple as that.” Finally, Ernie said, “They got the idea: If they gon’ treat me right, I'll come see them. If not, they lost a brother.” But in 1970, after they lost their mother, “everybody accepted Ernie,” Petie said.

In his soft voice, Holleran explained the predicament of being queer in a provincial place like Keystone, “I wasn’t out to anybody for years. In fact, that’s why I moved up North and stayed up North.” Petie Pickette also remembered how dangerous it was to be out then, citing bars in Jacksonville being evacuated due to bomb threats.

Holleran remembered a young man he knew from Windsor, a small village hidden off some back roads near US 301, who walked into traffic, killing himself, after he learned he had AIDS. But there were heartening stories, too — such as Ernie’s own death in Moccasin Branch.

“What happened in small towns is the ... thing that’s so marvelous about the South,” Holleran said. “What came through and overwhelmed whatever homophobia was present was the indomitable strength of the Southern family. I was just driving through Keystone the other day by the public beach where families picnic. And I thought: This is the thing that the South really has going for it: It’s this ability we have to celebrate family.”

In Holleran’s essay, “Ernie’s Funeral,” published in Christopher Street in 1988, he wrote: “Even in the hospital, he could not stop removing his oxygen mask to introduce whomever had just walked into the room to the rest of the people there or ask a cousin to move to one side because Anthony, seated on the window ledge, could not see past her, and no one should be excluded like that, Ernie said. There was no reason for anyone in his view to be excluded — and that included, of course, himself.”

Gary Dale Jolley and Mickler in Key West, 1986. (Photo courtesy of the University of Florida)

Petie Pickette recounted those last days with Ernie one afternoon in her backyard as thunder groaned and the sky turned moody. When the doctors told Ernie death was imminent, he asked to go home. In the living room, Ernie laid on a table made up as a bed. Beside him, his cousin Rosemary, his brother Hugo, Hugo’s wife, and Gary stood vigil. Purportedly, Ernie died, but then a knock came on the door just before midnight. His brother Hampton and his wife, Dorothy, called out, and the sound of his brother’s voice brought him back. Once Hampton reached Ernie’s side, Ernie gave up the ghost.

Before they left the hospital, Gary had brought copies of Ernie’s new book, which had just arrived at the house. Scrawled in what Holleran described as “the spidery, shaky, almost illegible handwriting of an old man,” Ernie inscribed a copy to Cal Yeomans. The inscription read, “I guess we’ll figure it out someday.”

Ernie’s wake was held at the St. Ambrose Parrish down the road from his house. At the end of a long canopy of live oaks lies a cemetery that harkens back to Ernie’s roots — markers bearing Minorcan names like Solano, Sanchez, Rogero, and Lopez. In Holleran’s essay, he wrote, “Ernie was contemporary. I watched him one night on the David Letterman Show, but he was also connected to the past, and when he died, a connection between the two was lost. So, it was doubly startling, and doubly touching, to drive to his funeral one Friday afternoon in mid-November — a funeral he had planned down to the music and food — and find one more place in which they touched. The menu is barbecued pork, baked beans, hot sauce, cole slaw, rolls, beer, and Pepsi. Cal and I sit with Gary and the nurses from the AIDS Network who helped Ernie through his last months. We are the gay portion of Ernie's life, in a room filled with his other parts.”

Pickette described the wake to me.

“People cried and ate and drank, danced, and carried on just like Ernie wanted,” she said. “That’s exactly what he wanted his wake to be like.”

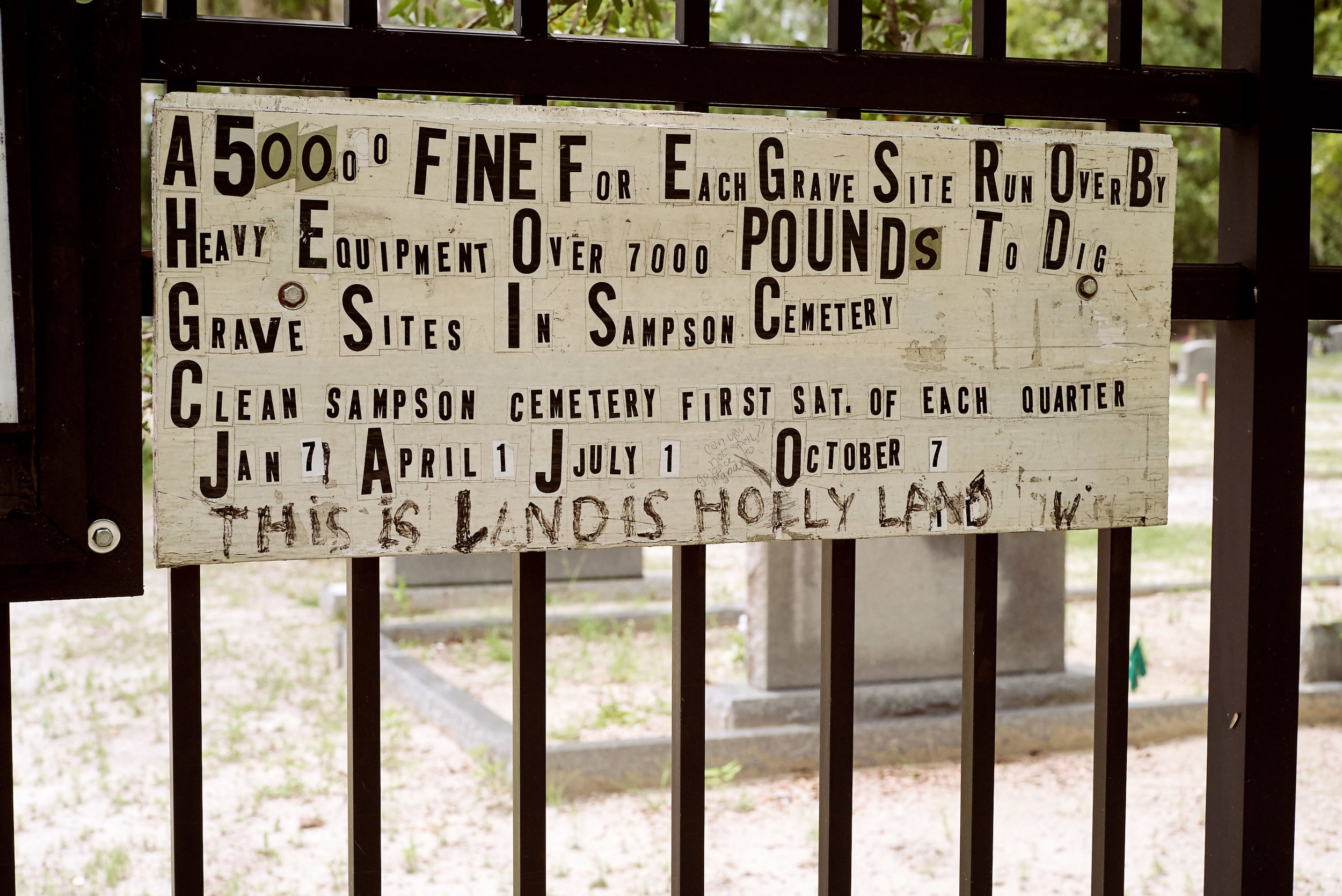

Folks catch up after the quarterly cleaning of Sampson Cemetery. Just down the road from their home in Moccasin Branch, Mickler and Jolley would stop at Odom’s Market for flowers or produce. (Photographs by Ernest Mickler)

When Ernie died, he was cremated. Afterward, Ernie’s brothers and their cousin, Ken, “buried Ernie’s ashes right beside his momma,” Pickette said.

At Sampson, where Ernie and 38 other Micklers rest, I visited during a hot summer morning with dark bands of rain looming above. At the gates, a soft, steady wind passed over the place. I could tell it must have changed tenfold since Ernie made his photographs here. Cookie-cutter cul-de-sacs spilled out all over the place, forming an endless array of terracotta roofs and manicured lawns.. To get to the cemetery today, you pass through a country-club development where even the speed-limit signs look ostentatious.

Winding down the four-lane promenade, signs pointed towards the cemetery that sits at the end of a road littered with sterile-looking stucco homes. I hooked past two-track trails falling off into woods, and then I reached the gated cemetery, flanked by a border of sparse pinewoods that separate it from the golf courses fanning out all around — a place time almost forgot. As I got out, a young boy passed by in a golf cart, pink polo shirt and frosted tips beneath a visor. I wondered what a passerby might have looked like when the road was only a coarse, oyster-shell path through the pines.

Inside, it didn’t take long to find Ernie’s grave, sandwiched between his parents, William and Edna Rae. A tabby-shell obelisk adorned with a silver plaque marks his place. I stood watch for a while, visited the places where Ernie stood. I thought about how he must have reckoned with death here where I stood, how he spent so much time over the years with friends and family, parents, and ultimately accepting that he might be interred here soon — Gary standing next to him as death crept in prematurely.

Out here in what was once was the middle of nowhere — now tame suburbia — I thought of how grateful I was to know Ernie’s work. All around, the state was vanishing, but Ernie preserved a chunk of it. The dimpled sugar sand and strewn pine needles conjured up Ernie’s photographs, Ernie too.

Ernest Mickler’s grave at Sampson Cemetery. (Photograph by Michael Adno)

In an interview in November 1986, on a local San Diego TV news show, an anchor asked Ernie what the essence of Southern people was. Without a skipping a beat, he told her in his honeyed voice, “Eating, laughing, and telling stories. They love that. They like life more than they like money,” and that incomparable gleam stretched across his face, just as contagious today as it was three decades ago.

Retracing Ernie’s footsteps this summer, I played Ernie and Pickette’s record over and over, memorized the lyrics, the chord progressions, the thin space between tracks. But one part stuck with me. Hell, it haunted me. About half way through the 13th track, “Rambling Boy,” Ernie croons in his light, confident timbre words that seemed to encapsulate his life:

Oh, when I die

Don’t bury me at all

Just place my bones in alcohol

And at my breast

Place a white stone dove

To tell the world that I died of love

For me, Ernie Mickler’s books, stories, and photographs gave me a sense of place, a well to return to. And for many, I believe Ernie forged a portal into the South — a South unto itself — proudly bound up in all its contradictions. He helped Southerners of all strata hold onto their roots, spanning the spectrum from blue-blood aristocrats to rednecks. But more specifically, he helped queer folks find that root in a place that — particularly during the AIDS plague of the 1980s — wanted to expel them.

The loss of Ernie and so many others like him in those years left a chasm in its wake.

As Edmund White wrote in an essay for The New York Times Magazine in 1991, “For me, these losses were definitive. The witnesses to my life, the people who had shared the same references and sense of humor, were gone. The loss of all the books they might have written remains incalculable.” He continued, “The grotesque irony is that at the very moment so many writers are threatened with extinction, gay literature is healthy and flourishing as never before. Perhaps the two contradictory things are connected, since the tragedy of AIDS has made gay men more reflective on the great questions of love, death, morality, and identity, the very preoccupations that have always animated serious fiction and poetry. Or perhaps AIDS has simply made gay life more visible.”

Following Ernie’s death, some obituaries listed no cause of death or “bone cancer,” possibly at the family’s behest.

“There was a stigma about it,” Pickette told me. “It was like anybody knowing you were gay, period. If you had AIDS, obviously you were.” But some papers, namely the New York Times and the Key West Citizen, printed AIDS as the cause.

A few weeks after Ernie died, Pickette drove down to his house. She found it abandoned — just a cardboard box filled with “White Trash Cooking” press materials left inside.

“Gary let nature have it,” she said. Out on the porch, there was one hanging plant — withering. She threw the plant and box in the car and took off.

In Pickette’s backyard this past summer, the sky molted into a dark, purplish gray, threatening to open up. Just behind us, a 20-foot-tall bird of paradise plant stretched up into the troposphere, dwarfing the greenhouse behind it. The plant had grown as tall as the cabbage palms that line the perimeter of her house. This bird of paradise is the same plant Pickette rescued from Ernie’s house 30 years ago. She called it her “Ernie plant.”

I asked which of her memories of Ernie is strongest, 30 years after his death. She didn’t furrow a brow or dwell on the answer for long. She just looked off toward the top of her Ernie plant and beamed.

“It’s his energy,” she said. “His spirit is what I carry with me — his smile.”

Ernest Mickler at home in Moccasin Branch, Florida. (Photo courtesy of the University of Florida)