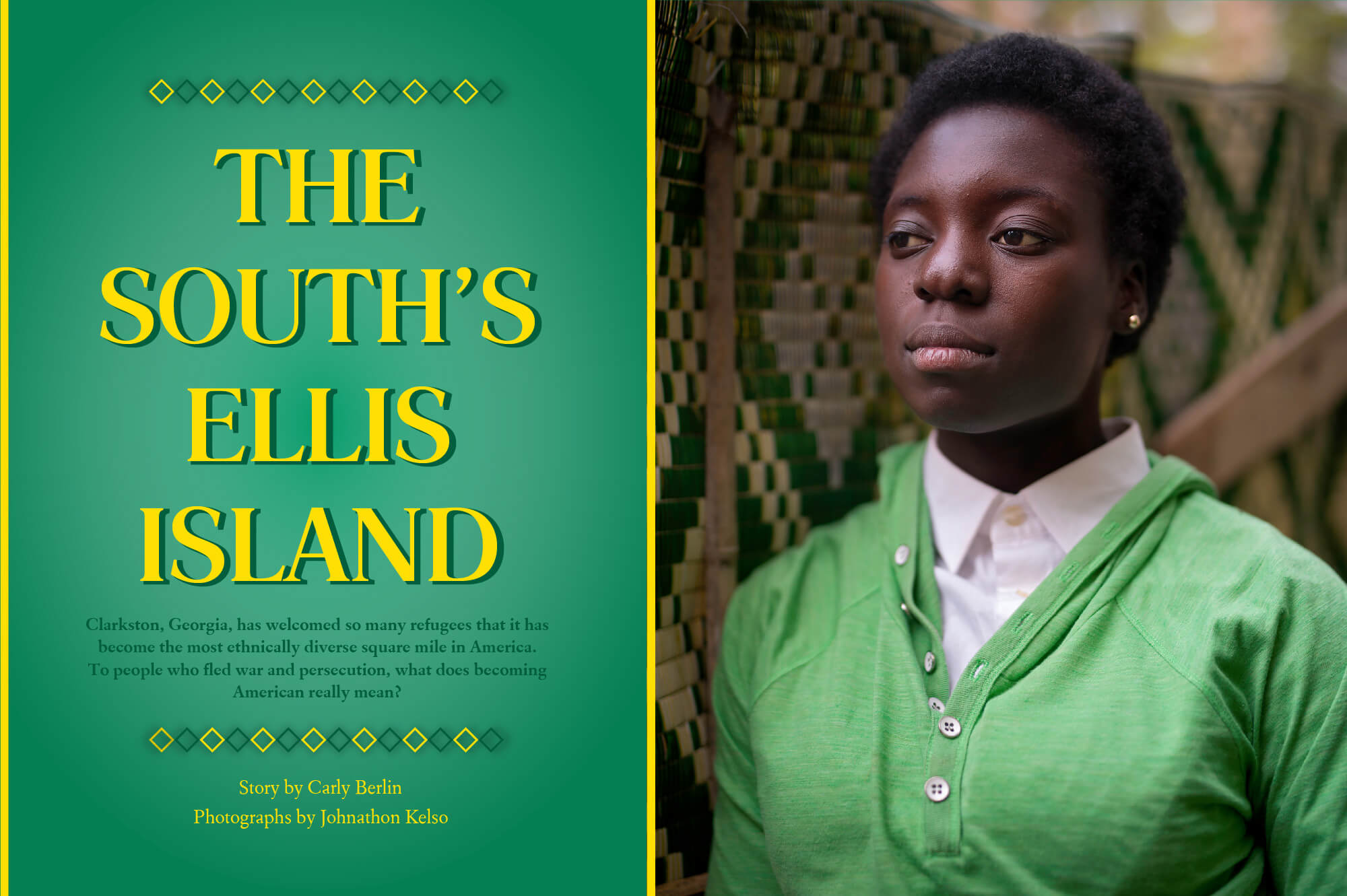

For 40 years, a small town east of Atlanta has welcomed people seeking refuge from the world’s wars and persecutions. For more than 60,000 refugees, Clarkston, Georgia, has been their first American home, and the town has become the most ethnically diverse square mile in America. Carly Berlin spent the summer interviewing refugees and community leaders to learn what America and the South mean to them.

Story by Carly Berlin | Photographs by Johnathon Kelso

When Naing Oo came to Clarkston, Georgia, in 2003, he had an envelope hidden in his backpack.

Oo’s family came to Clarkston from Myanmar, the country formerly known as Burma, as political asylees. The envelope, which held his family’s case notes, came from the United States government. To conceal it from Burmese authorities, it was nestled among belongings in the backpack of 11-year-old Naing — whose vision of America came from Hollywood movies, who knew little of why his family was uprooting, and didn’t even know he was carrying the envelope.

Oo, now 27, has little recollection of the circumstances that led his family to resettle in Clarkston. He had lived in Yangon, at the time Myanmar’s capital and most populous city. The violence, wrought by the military and by Buddhist extremists who wanted Rohingya Muslim people gone, occurred outside the city, in villages “where the stories don’t really get out.”

Get out is what Oo’s father had to do. He had protested in support of a democratic government, a potentially deadly endeavor given that since 1962 Myanmar has been controlled by a military junta that vowed to track down dissenters. The Oos, also, practice Islam.

Naing does remember that his father lived in New York for three years before the rest of his family came to America and decided to relocate again, to Georgia. His first American memory is of climbing the escalator at Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, and having two people convince his family to pay them one hundred dollars to carry their bags. “We got played. That was my first impression of the States.” Naing remembers that when he stepped outside that day, he turned back into the airport, shocked by the cold December air. Wide-eyed from jet lag, he recalled his “weirdest first snack.” A bag of Doritos and a glass of milk.

During his first few weeks at middle school, a representative of the International Rescue Committee’s Youth Futures program took Oo to Cici’s Pizza after school. When Oo returned home, he saw police cars and his crying mother outside. “They had no idea where I was.”

To meet with Oo, I visited the Atlanta-area headquarters of the International Rescue Committee (IRC), situated in an office park north of Clarkston. Fourteen years after he arrived in America, Oo now works for the IRC, helping new refugees. His job in the IRC’s Youth Department is part of the committee’s year-old Connect to Success program, which works with refugee youth who are not enrolled in school and provides them with career-readiness workshops.

Outside his office, the waiting room overflowed with people who had fled persecution and conflict the world over. On Thursdays, the day I visited, people travel from across Georgia to meet with their caseworkers, to discuss citizenship status and green-card acquisition. Recently, the IRC — one of five federally regulated resettlement agencies working in the Clarkston area — has suffered severe budget cuts and reduced its staff of caseworkers. That Thursday, in mid-July, only the first 25 families in the waiting room could be helped.

“It’s a full circle,” he said, sitting in a conference room near his cubicle, wearing a button-down shirt and deck shoes. “As a refugee, my clients get to see that, ‘Hey, this guy is from Burma. He was where I am right now.’ It has been really helpful in terms of connecting with my clients. The lessons that you’re learning are a lot more than you’re giving.”

Naing Oo fled Burma with his family at age 11. He worked for the IRC at the time of this interview

For those with a penchant for superlatives, Clarkston is “the most diverse square mile in America.” For folks searching for a regional comparison, it is “Ellis Island South.” For others, it is the “University of America.” For about 12,000 people, it is home.

For decades, Clarkston’s paved roads were few and its goat farmers many. When Interstate 285, which encircles metro Atlanta, was completed in 1969, Clarkston developed into one of Atlanta’s earliest bedroom communities, just east of the I-285 perimeter. In the mid-1970s, Clarkston began seeing its first refugees: part of a wave of 300,000 Southeast Asian migrants who entered our country, due largely to the U.S. attorney general’s parole authority, in the five years following the fall of Saigon. As Congress grasped the scale of this refugee migration, it passed the Refugee Act of 1980 to standardize resettlement services for all refugees entering the country. The U.S. then formally adopted the United Nations’ definition of a “refugee”: someone who has been forced to flee their country because of persecution, war, or violence; who has a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.

As many white residents fled farther out to more fashionable developing Atlanta suburbs, Clarkston became perfect for refugees, with its hundreds of vacated apartments and access to public transportation, a post office, and a grocery store, all within walking distance. The little city became one of now 190 designated resettlement communities across the country.

And so here came Somalis fleeing civil war, Bhutanese fleeing ethnic cleansing, Eritreans and Liberians, Croatians, and Cambodians, and all who make up the now 100 different ethnic groups who have begun their American stories in Clarkston. Their stories all start with persecution. Some, like Oo’s family, are political asylees who have sought protection by submitting an asylum application to the United States, after arrival here. Most, though, are refugees, who have lived in a refugee camp and have undergone the vetting process of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, which takes a year, as well as that of the United States, which takes an average of 18 months to two years, as compared with four months in Canada. Before departure for the U.S., all refugees sign a promissory note agreeing to repay the U.S. government for their travel costs. All have worked with one of nine domestic nonprofits—most of which are religious organizations— with which the State Department works to resettle refugees. Many have participated in literacy and enrichment programming at places like Friends of Refugees, a nonprofit that has worked with Clarkston’s refugees for decades. All enter the U.S. with refugee status, which they retain for 12 months, at the end of which time they are required to apply for permanent legal residency or green card holder status. All are given a small sum of money as a gift, not a loan, and all recipients are expected to live off those funds for three months. During that time, immediately after arrival, refugees who are able to are expected to begin seeking work.

Some 60,000 refugees have called Clarkston, and nearby neighborhoods, their first American home. That’s about 2,000 per year, on average, since 1980. A fraction of a fraction of a fraction of the world’s refugees live — or have lived — in Clarkston. And yet refugees have put this Georgia city on the map.

We like to talk about the “New South.” I spent this summer speaking with refugees who have learned, and are learning, American life in our region. These new Southerners live on this land and have a rare, if temporary license: to know this fraught region without its history, its context. As an Ethiopian man named Hukun Abdulla, put it to me: “We don’t go anywhere. We think this is America. That’s it.” I talked to people in Clarkston about what home means in a place where many come from elsewhere, because that elsewhere expelled them. We talked about living in a city where many did not choose to live, but were relocated by government officials. We talked about how to talk about where we come from.

I began reporting this story as a white liberal-arts college student from Atlanta who thought she knew a thing or two about the South, and about America. I’m writing this, still that woman, with the realization that I know precious little about anything. Part of this is because when we talk about Clarkston, we’re not just talking about metropolitan Atlanta, or Georgia, or the South. We’re not just talking about America. As Malek Alarmash, a Syrian refugee who resettled in Clarkston in the summer of 2016, said, “In Clarkston, we can see the whole world in a small city.” And, here, sometimes, we can even see the universe.

A map on the wall inside the Friends of Refugees office, with pins showing the dozens of countries Clarkston refugees once called home.

Lauren Brockett, Director of Employment Services at Friends of Refugees, prays with a fellow employee before the work day begins.

These four families — the Way Htoos, the Law Wahs, the April Paws, and the Mu Shis — are refugees who fled violence from their homes in Burma. They now live in Clarkston.

In the world of Pat Maddox, God does things like “move chessmen on the chessboard into place,” and “pick up the tapestry and begin to weave the story.” This holy chess game led her to found the nonprofit Friends of Refugees. Her story, if she had to title it, would be, “The Journey Almost Missed.”

As she sat at her kitchen table, Maddox, 79, recounted the moves of the game, the strands of the cloth. She spent her childhood largely in Clarkston, and returned 20 years ago to take care of her aging mother. Then, she saw an ad in a newspaper asking for volunteers to aid Bosnian new arrivals; she saw Iraqi children playing in the snow, wearing flip-flops. With the help of local missions, Maddox began to provide programming for children at a handful of Clarkston’s 36 apartment complexes.

“God again instructed, ‘Outsource yourself until the help comes,’” Maddox recalled. What became Friends of Refugees — an organization that aspires “to empower refugees through opportunities that provide for their well-being, education, and employment,” as its mission statement expresses — originally grew out of the Clarkston International Bible Church (CIBC). First came a summer camp with a waiting list, then a family literacy program for mothers and children, and later a sewing society which sells dolls in the image of the women who make them. There is a community garden where refugees use the farming skills they bring from their home countries, a career hub where they learn how to write resumes and hold job interviews, and a business accelerator program. In 2005, Friends became an official nonprofit, independent of the CIBC. Susan McDaniel, director of volunteer engagement for Friends, called the organization “faith-based,” and added, “we do what we do because of what God did in our lives.”

I attended a Friends volunteer orientation that McDaniel led. After the initial icebreakers — attendees sharing how they’d heard of Friends — McDaniel walked us through what we might call an empathy training, an attempt to help volunteers understand what refugees go through before arriving in Clarkston.

“Count the people in your immediate family,” she instructed. We were to hold this number in our minds.

“All of these people live in the Atlanta area. Now, another country attacks the U.S. as an act of war. When was the last time this happened?”

“9/11?” someone suggested.

“Pearl Harbor,” another answered, correctly.

McDaniel continued, “Imagine you wake up one morning and there is an attack on Atlanta. There’s the second amendment, and this is Georgia, so some folks might fight. Most will pack up and leave. So, who has family in another state in the Southeast?”

People offer the Carolinas, Florida (hell no, too easy to attack). We settle on Roanoke, Virginia.

“At first, it’s like a family reunion in Roanoke,” McDaniel said. “But you’re always watching the news to see when you can return to Atlanta. You’re there for a week; things are getting worse. You hope the kids packed the PS4 or some books. Then, it’s two weeks, a month, and you start homeschooling the kids. Then, war reaches Roanoke. Where to next?”

Oklahoma? Texas? (Definitely not; they’d secede.) Next stop: Kansas City, Missouri.

In Kansas City, the banking infrastructure has fallen apart, and you aren’t able to access your savings. Grocery trucks can’t get through, so food is incredibly expensive. You can’t get gas, so you fill up extra tanks as a precaution. You sit in Kansas City for two months. War comes. You decide on Phoenix as the next stop. When you’re almost there, you run out of gas, so you start to walk; you have to leave grandma behind; you sleep in the woods or in abandoned buildings. Another group breaks down the doors to a grocery store and invites you to go with them, and you think, four months ago I had a good job, and now I am a thief. Internet connectivity is spotty, so you trade information with vehicles you see on the road. But, one day, a truck stops and people jump out, and you realize these are soldiers trying to catch you. You, and the remaining members of your family, disperse, all hiding in different places. Later, you don’t know if they’ve been killed, or have kept on toward Phoenix without you. You continue on. You avoid vehicles. But one day, a U.S. Army truck appears, and soldiers take you in. They drive across the border into Mexico, and they drop you off at a refugee camp, and you get in a long, long line, and you fill out long, long paperwork. Finally, it is determined that you can stay here. There are mattresses on the floor, a heater, a pot, a pan.

“This is your new home,” McDaniel said. “It is a place of refuge, but not a place of purpose.

The Uhuru African Dancers pose for a portrait during rehearsal at the Clarkston Community Center. Uhuru is the longest-running African dance company in the Atlanta area.

In founding Friends of Refugees, Maddox has created an organization devoted to helping those who have already arrived in the United States gain self-sufficiency and lead fulfilling lives in a new country. In 2015, Friends volunteers provided 40,000 hours of service for over 4,000 refugees, under seven program areas. These programs saw hundreds of job placements, served 150 children in summer camp and afterschool programs, taught English to hundreds of mothers and kids, filled more than 90 families’ kitchen tables with fresh produce from the Jolly Avenue Garden, created thousands of individually crafted items in the Refugee Sewing Society, and helped launch 16 new businesses through the Start:ME business accelerator. In Clarkston, with the help of organizations like Friends, 89 percent of resettled refugees are self-sufficient six months after arrival — better than the 74 percent national rate.

To the current executive director of the organization, Brian Bollinger, “Being a friend of refugees is not an act of pure charity. It is an act of faith and hope, because when our refugee neighbors flourish, we flourish. When they do not have the opportunity to bring to our community the full force of their ambition, we are the less for it, our families are the less for it, and the city is the less for it. We have faith that they have not survived to languish in our community. You can’t tear apart individual flourishing from that of the surrounding community. Friends is about individual responsibility — but responsibility to the community, not for it. The difference between these is the essence of Friends of Refugees.” Maddox described the purpose of Friends as “relational, to prevent isolation.” She sees the organization as enhancing the lives of refugees and aiding individuals in becoming safe, strong citizens.

For Maddox, this dedication reaches into her own home. In the time I spent at Maddox’s place, two summer campers played in the front room, waiting for their parents to pick them up. I could hear their discussion — “on the American flag, white means freedom and blue means justice” — drifting into the kitchen. Two students of Lithuanian Christian College, one from Zimbabwe, the other from Bangladesh, lived with Maddox for the summer as they participated in a Chick-fil-A leadership program. She spoke with delight about how they enjoyed the cookies she’d bought the day before. Maddox’s own grown child passed through, saying hello, as she rummaged through the cabinets. Outside this low ranch house on a side street in Clarkston, there were bicycles and a basketball hoop and an Oldsmobile in the driveway, with a black oval bumper sticker bearing simple white lettering, spelling out the name of the United States’ 45th president. I had assumed, before going inside, that the car must belong to a visitor.

“I voted for Trump,” Maddox said. “I had gotten tired of our existing government, and everybody got really upset with the ban. It’s only temporary until we can figure things out. Because the countries that are banned don’t have good governments. They’re not vetted well. For the majority, refugees want a safe home. Education for their children. A job where they can produce for themselves.”

President Trump cut the proposed number of refugees admitted to the United States this year by over half. The 50,000 refugee limit, already reached this year, is the lowest ceiling since 1980; in recent weeks, White House administrators have pushed for an even lower bar. These minimal quotas would be held in place if Congress passes the Reforming American Immigration for Strong Employment (RAISE) Act. Backed by Georgia’s own Sen. David Perdue, the bill, along with its limited admittance of refugees, favors immigrants between the ages of 26 and 30 with a doctorate, a high English proficiency, and a job offer with a high salary. Having won a Nobel Prize or an Olympic medal enhances one’s chances significantly.

I would not gain entrance into the U.S. under these guidelines; neither would have Oo and his family, and the refugee families I spoke with would have had significantly lower chances of securing admittance to the country. I was the first to tell Maddox about the new proposed legislation. She said, “I think if they’re in danger, they need to come. Bottom line. We’ve never experienced this in America. I hope we never will.”

I have found myself continually questioning the logic of a woman who has restructured her life because of her deep and personal care for refugees, yet who voted for a man who ran, and acts upon, a campaign against them. Clarkston is a place that challenges neat conceptions, and Pat Maddox is a person who holds all of these contradictory stands in her arthritic, yet capable, fists.

Maddox told me that she has two “desires.” One is for Friends of Refugees to duplicate itself. However difficult that would be, Maddox said, it would be “worth it. When God’s design is that you give away, it multiplies.” Her second desire — her final note, before wishing me a blessing on my story—is “that no one misses their journey.”

Rohingya refugees take part in a rally protesting the genocide of the Rohingya people in Burma. The rally, led by Clarkston Mayor Ted Terry, was held at Memorial Drive Presbyterian Church on September 1, 2017.

Pictures of children from the Willow Branch apartment complex in Clarkston hang in the leasing office. The children are part of an afterschool program run by a nonprofit called Star-C.

Friends of Refugees Founder Pat Maddox — aka "St. Pat of Clarkistan" — at the Forty Oaks Nature Preserve, just next to her property in Clarkston.

“It’s hard to get used to being free,” Nathalie Wibabara told me. “It was surreal. Even when I came here, it took me a year or two to really feel like I’m actually free, and that no one is going to oppress me.”

Wibabara arrived in Clarkston on February 17, 2000. She was 18 years old and came with her family as refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Fifty years prior, Wibabara’s parents had immigrated from Rwanda, in East Africa, to the Congo, in the West. In 1998, the Second Congo War erupted between the Rwandan and Congolese governments. And because Wibabara’s family hailed from Rwanda, they were targeted by the Congolese authorities. Officials appeared at the Wibabara home in August of that year, taking all that the family owned — everything from the liquor in their store to the mattresses they slept on — claiming these as the domain of the Congo.

“We spoke like them and behaved like them, but physically we looked different,” Wibabara recalled. “We’re just glad they didn’t kill us.” The uncles she lived with were arrested, along with all other Rwandan men; only the women and children lived together. For a month, “anyone could come to our house and steal from us, or do whatever they like.” Unable to attend school, go to the market, or fulfill any basic deed of life, Wibabara and her remaining family members were recognized as refugees by the Red Cross.

They remained confined to their home. The Congolese government brought other Rwandan families living in the vicinity to the Wibabaras’, and “basically made my house like a prison,” Wibabara said. Six or seven people slept on one mattress, and Wibabara slept poorly. Security guards were stationed outside the home, to protect its inhabitants. Wibabara and the others ate fufu, a combination of beans and corn flour, “like grits.” This lasted a year. In July of 1999, Wibabara and her family transferred to another city: one that had converted from a convent to a prison. Many had recently fled to Rwanda, where their families may have come from but they had never been.

There, Wibabara learned that her family was granted refugee status and would be admitted to the United States. First, though, they endured five months in a refugee camp in Benin, West Africa. This is where people became religious.

“They didn’t know how long they would be there,” Wibabara said. “Their only hope is to pray to God.” Wibabara, who had grown up Catholic, watched as many converted. Some didn’t, because there were others praying for them. Wibabara, along with other adults, fasted as she worshipped. When she got to Clarkston, she still ate only once a day. This is what she was used to. “I felt like I was gonna die,” she said, with a chuckle.

Wibabara took her first English as a Second Language class in the same building on Church Street where she now works as a refugee-employment specialist for the Friends of Refugees career hub. On her desk is a jar filled with miniature flags of many countries; on the walls are whiteboards, with notes and questions:

Proper way to write dates in the U.S.A

How many industries/fields have I worked in my life?

What have I always wanted to learn?

One morning in early August, Wibabara coached Hukun Abdallah as he prepared for a phone interview for a warehouse inventory position. They talked about the difference between “I think” and “I will.”

“I will stay calm and do what needs to be done first,” Wibabara modeled. “I will look for work to do whenever there is downtime.” Abdallah left the room when his phone rang with a call from his potential employer.

Wibabara herself earned her GED while simultaneously training at Grady Memorial Hospital through a program called Job Corps. She attended the University of Georgia and received a degree in microbiology. She lived in New Jersey, and then in San Antonio, where she attended school to become a physician’s assistant but dropped out when she had trouble sleeping, sometimes remaining awake for over three days at a time.

“The doctors thought that maybe it was because of the war, but I don’t think I was traumatized. I mean, compared to people that have been through worse than me,” she said. After a brief stint in Orlando, she returned to Clarkston to take care of her mother. Along with her work for the Career Hub, Wibabara is also launching her own travel business through Friends’ accelerator program, “to help refugees go back home” to visit their families.

The philosophy of Friends suits her. Employees pray each meeting, she said, though they aim not to force their beliefs.

“We are here to serve everyone,” Wibabara said. She and her coworkers do not ask those they work with about their religious backgrounds. “We aim to serve, not to preach. But we preach through serving, by showing people we love them.”

A little while later, Abdallah returned to the classroom. He got a second interview. We cheered.

Nathalie Wibabara, a refugee from Democratic Republic of the Congo who now works as a refugee-employment specialist for the Friends of Refugees.

Malek Alarmash wanted to go to the beach. He has lived in Clarkston for a year; he grew up in Syria, left in the middle of earning his college degree to spend three and a half years in a refugee camp in Jordan, and this summer, he planned to visit Savannah or Miami, his first trip outside of the Atlanta area. Alarmash does get to travel for work, though: He is a barista for Refuge Coffee, and has served up espressos in a refurbished Chevy truck across town since October 2016.

Refuge Coffee aims to provide a multiethnic gathering place in the heart of Clarkston. Founder Kitti Murray saw a “hospitality gap” when she moved to Clarkston five years ago; now, Refuge flourishes on the corner of Market Street and East Ponce de Leon Avenue, in the shell of a 1960s service station. Even on the hottest summer days, folks fill the picnic benches. The garage — which used to house a pharmacy where a young Pat Maddox would go with friends to drink Coke with peanuts after school — now holds Square Mile Gallery; a rotation of flyers about citizenship classes and community center gatherings always amasses on the outer wall. Refuge itself provides job training opportunities and employment for resettled refugees.

Alarmash comes from a place where hospitality is engrained.

“When you come to the houses of Syrians or Arabs in general, you have to have food, you have to have tea after food, coffee, desserts,” he said. “It’s part of our culture that if we serve you a food and you were to say, ‘I cannot eat anymore,’ we would say, ‘Why? Is there something wrong with the food?’ We didn’t understand this because we consider it part of our culture that if you come to our house, you are very welcome. This is our home, and we welcome every guest.”

Malek and his mother, Majeda, are starting a catering business that, too, hinges on hospitality. When Majeda began vending home-cooked Syrian food at the Clarkston Community Center, Malek saw how much people loved his mother’s kibbeh and baklava. He decided to call their venture Suryana Cuisine, and hopes that, in the future, the business will offer job opportunities for refugees in the community. Already, the two have prepared meals for groups with Friends of Refugees, and for a recent event at their mosque, Masjid Al-Momineen, in Clarkston. The premise was to invite non-Muslims into the mosque, to help provide understanding.

“We were part of the bridge they were building through the food,” Alarmash said.

At 24, Alarmash must provide for his family. “Having my age,” he said, “or respecting my age, or enjoying my life and time, it’s hard to do both.” He hasn’t studied for five years. “It’s hard to start again in Jordan, and start again in the United States,” he said. He didn’t get to go to the beach this summer; he had to stay home to study for an exam in management, and help get the family business on its feet.

But Alarmash insisted, “I’m the kind of person that’s like, ‘I can do it.’ I’m saying to myself, ‘I have a dream. I need to do this.’ So, it’s challenging. But we are having a great time. We are having a great experience. Learning from every moment and trying to enjoy our time.”

Malek Alarmash, a Syrian refugee, in front of Refuge Coffee, where he works in Clarkston.

Hani Keddo with his Lovebird. Before he and his family were resettled in Clarkston, Hani owned his own shop in Syria that sold handbags and shoes. However, his shop was bombed, and he lost everything. Hani now drives a van pool, helping others in the Clarkston refugee community who need transportation.

A young girl holds the branch of a Crepe Mrytle tree. Her family fled violence in Burma and they have been living as refugees in Clarkston for over three years.

I spent much of my summer thinking about what learning means.

Before refugees, and asylees, arrive in Clarkston, they must learn how to fill out extensive paperwork; to navigate Atlanta’s vast Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport; to find those who will bring them to Clarkston. Then, they must learn where the grocery store is, where to send their children to school, to speak a new language. They must learn to shake hands, to look people in the eye. They learn to eat Doritos and milk. They learn from God. They learn microbiology. They learn to write résumés. They learn how to make coffee, how to start a business. “The lessons that you’re learning are a lot more than you’re giving.” What have I always wanted to learn? “Learning from every moment. And trying to enjoy our time.”

I entered Clarkston on a selfish enterprise. I saw my own origins in the people settling here anew, just as my family — Jews fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe — planted new roots in the American South. The crisis that unfolded around my grandparents, in the wake of World War II, prompted much of the legislative infrastructure that today allows refugees to make their homes in Clarkston.

My grandparents lived in the Jim Crow South. These New Americans, New Southerners, have arrived in a place that promises both hope and prejudice; both opportunity and oppression. These are the layers—and, the contradictions— of a place that I have learned to see.

I think that learning is also, often, about losing. I know little to nothing about Lithuania and Poland, the stomping grounds of my ancestors. I met people in Clarkston who dove deep into America, who have voted in a democracy for the first time in their lives, who have run for office. And I have met people who surround themselves with those who are familiar and comforting, who cannot speak a lick of English, but who sit outside on hot day after hot day selling the jewelry they make by hand.

I have met people who, like Nathalie Wibabara, say: “Because the Congo kicked me out, it’s not really my home. I went to Rwanda in 2008 for the first time, but culturally I felt like I didn’t belong there. Clarkston is my only home. Georgia is my home.” I have met people, like Naing Oo, who say: “There is an expectation period that you go through where you realize that America is not what you’ve seen from Hollywood. The truth is that to be truly American, a lot of people think you have to be surrounded by white people.” Oo recently returned to Myanmar for the first time since his family fled. When he marveled at old kingdoms, active volcanoes, and rescued elephants there, his relatives who had remained said, “You don’t know how it used to be.” At the beginning of August, Oo moved to New York City to take a job at BronxWorks, another resettlement charity. He ultimately hopes to become an immigration officer, even though federal hiring for those positions is frozen, at least for now.

At Refuge Coffee one day, I met a man named Usman Sule. This is what he told me: “Someone is going to walk past us while we are having this conversation and they’ll be like, ‘Where are you from?’ I’ll say, ‘I’m from Africa.’ Then, the African from the next table will look around and be like, ‘Where in Africa are you from?’ Then, I tell him I’m from Nigeria. A Nigerian would look at me and be like, ‘OK, where in Nigeria are you from?’ I’m from a certain state. And it doesn’t stop there. It’s confusing. Growing up in Nigeria, my parents are from two different states, and they come from two different tribes. Your father’s language is what you are. I am from a state named Benue state; it’s in the middle belt of Nigeria. Even right there, within, these questions don’t stop. Down to your very, very village, they want to know what part of the village you are from. Are you from the upper part or the lower part? At what point are we going to be like, OK, you know what, this common humanity that we are blessed with, are we going to exploit, are we going to limit? We are blinded.”

Sule prefers a more cosmic approach. “Do you know where I am truly from?” he asked. “I am from the universe.”

Assimilation is an odd beast. It forces forgetting; it craves a compression of culture, and the melting pot it stews serves up something hard for many to swallow. Living in a nation of immigrants means living in the tension between moving forward and looking back. The South, at times a close acquaintance of the beast, at times its nemesis, knows this deep, deep in its bones.

We’ve got a lot to learn.