By Josina Guess

I live in a place where the wind blows history into my path.

Naturalists say chance favors the well-trained eye. If you study any habitat, its flora and fauna, you are more likely to recognize what is hidden in plain sight. But the thrill a birdwatcher feels when that rare bird crosses their eye feels like more than chance, more than a convergence of luck and preparation. That flutter of wings and feathers, that talon on a branch, that moment of avian eye contact, that song you’ve been waiting to hear, all feel like a holy gift.

But the story that landed in my path is a terrible one — the 1947 lynching of Willie Earle in Greenville, South Carolina, and the subsequent acquittal of his killers. Nevertheless, it revealed itself in my yard, like a bird I had been expecting in this landscape that carries memories of racialized violence.

When my family and I started to settle into our northeast Georgia farmhouse two years ago, we found a box of Athens Banner-Heralds and Atlanta Journals and Atlanta Constitutions from the mid 1940s through the early 50s. I pored over the brittle yellow papers, a time capsule of this region’s attitudes on race, gender, economics, politics, and agriculture. I wondered at the treasures hidden in those stacks, and what coverage, if any, I might find of some of the racialized terror and lynchings of those waning days of overt American apartheid. But as the weeks turned to months, then years, those papers kept falling to the bottom of my list of priorities. We kept the papers in the closet for a while, but I finally conceded we needed the space more than I needed those old stories — we have the internet, after all.

As a generational hoarder, I thought of their usefulness or marketability. I considered the projects they could become: decoupage trunk linings, wallpaper, or multimedia collage. I imagined myself selling them to the highest bidder online. Early last fall, I decided to just let them go — sort of. When I asked myself Marie Kondo’s question — “Do they spark joy?” — my body answered with a resounding, “No.” As an interracial woman in an interracial family living in the rural South, I want to balance my awareness of all the current and historical forces that would negate our existence with all of the things that will help healthy communities thrive. I hold on to many artifacts from the past, both painful and beautiful, but I didn’t want to hold onto all of those papers. When my husband Michael suggested moving them out to the woodshed, I did not protest. I accepted that I was not going to deal with them. At least those unread stories could become useful garden mulch. (Oh, saints of hoarding and the perpetually overwhelmed, please forgive my transgression).

During a blustery autumn storm, the tailwinds of a hurricane, the wind whipped through the woodshed and stirred up some of the papers, littering them around the property. Each day we would pluck a few — a strange harvest of stories. Opinion columns about communists clinging to the blueberry bushes; by the smokehouse, a story of a man dying because a segregated hospital refused him treatment; in the kale I found the price of cotton: 36 cents per 1-inch middling. I would nibble on these stories, roll them over in my mind, then bury their empty husks beneath a pile of oak leaves.

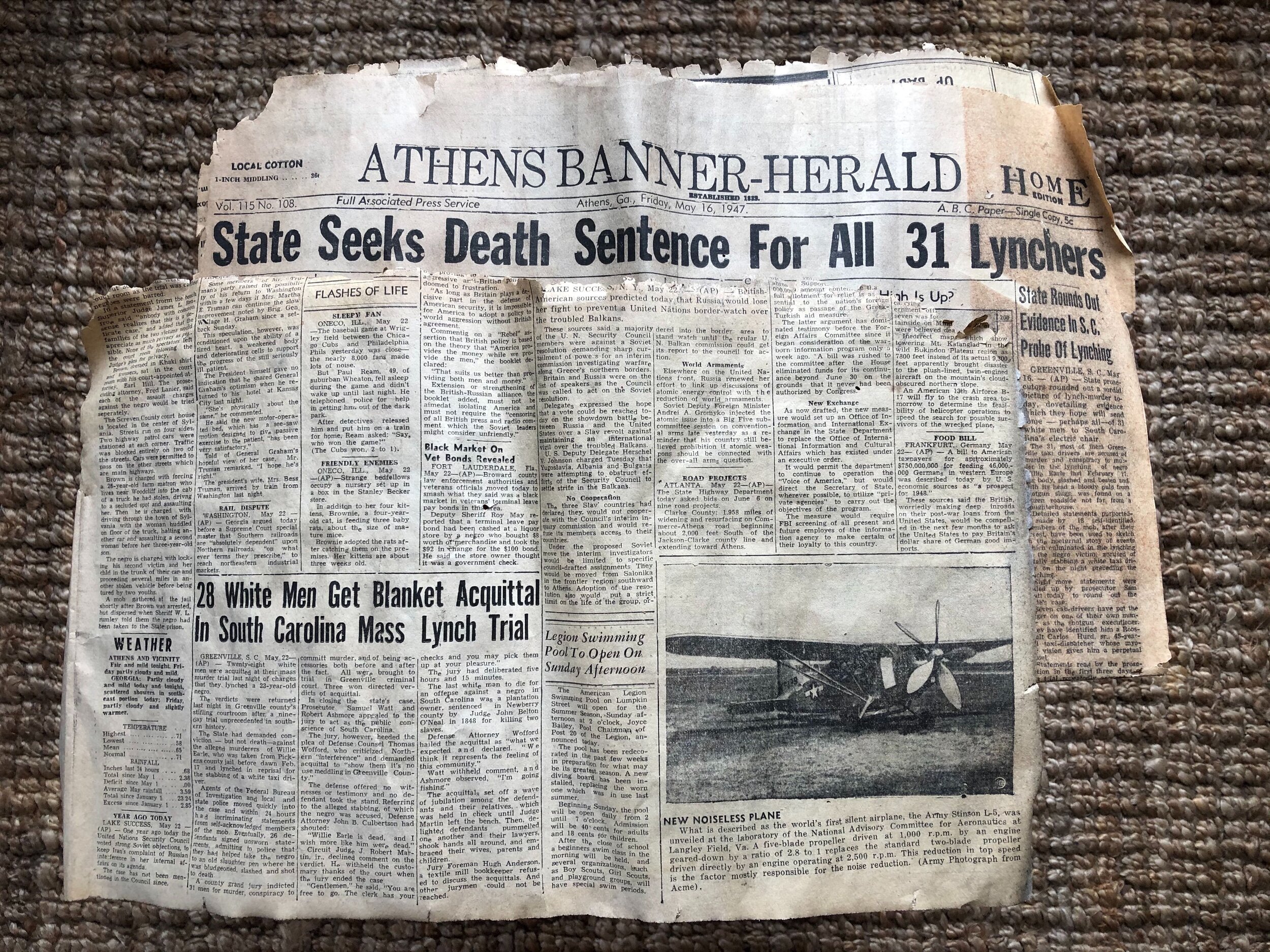

Then a keeper appeared to Michael in the grass between the old well and the pecan tree. The front page of the Athens Banner-Herald from May 16, 1947 read, "State Seeks Death Sentence For All 31 Lynchers." He lifted the dampened page and laid it to dry on the dining room table. The article gave graphic details and ample evidence, including confessions and incriminating accusations from the taxicab drivers who killed Willie Earle to avenge the fatal stabbing of a cab driver named Thomas Brown. Arrested, then almost immediately kidnapped from jail, Earle had no opportunity to stand trial - his guilt or innocence never proven. The cab drivers behavior followed a recognizable ritual of extrajudicial killing that terrorized African American communities throughout the South from the 1870s through the 1940s. When the paper dried out, I tucked it away on the bookshelf. I thought about rifling through the stack for the follow-up paper, or I could have done a quick internet search to know what date the trial ended and the dismal outcome. Instead, I set the incomplete story on the shelf for another day.

I told myself to look up Willie Earle’s story, but the holidays were upon us — I let the details of his murder and the fate of his killers fall to the wayside. Though I have been researching this area's violent history, it takes an emotional toll to read these tragic stories — a toll I was not yet ready to pay. I try to pace my consumption of tragic news, a privilege but also a form of soul preservation. But then, the rest of Earle’s story blew into our front yard one balmy Saturday in January.

“What is this all about, Josina?” My friend was standing in the front lawn, staring at a piece of damp newspaper. We had just finished brunch with two families who live in Athens, Georgia. Our house is something of an informal retreat space for activists, academics, and artists wanting to connect to the land. Leah Penniman, author of Farming While Black, named how the land itself was not to blame for the traumas that our people bore upon in it. Some of “[o]ur grandparents fled the red clays of Georgia, and we are now cautiously working to make sense of a reconciliation with the land.” These friends who were visiting our farm share the burden to remember and lament racialized violence — both past and present. Our work, studies, conversations and personal lives point to the unfinished business of dismantling racism and building up that Beloved Community. I had just been telling them about my new job and how The Bitter Southerner will soon help publish a book with the Music Maker Foundation about a North Carolina luthier named Freeman Vines and his Hanging Tree Guitar project. Vines has made something beautiful from a vile artifact — guitars from the wood of a lynching tree.

So, my friend wondered — for a moment — if I had placed an ancient newspaper in our front yard as a ritual or a continuation of our ongoing conversations about healing ourselves and this landscape. She had walked out front to check on her husband, who was leaning against a log, trying to soothe their infant to sleep when the paper caught her eye. Her eyes were fixed on a shred of paper that blended in with the browning edges of the winter grass and she looked back at me. “Why is this here?” The urgency in her voice told me that she wasn’t just scolding me for keeping a messy yard.

I walked to where she stood and read the headline on the bottom half of the torn paper that lay at her feet. From May 22, 1947: "28 White Men Get Blanket Acquittal in South Carolina Mass Lynch Trial."

“The wind found it!” I gathered up the damp remnant and ran into the house. “Come, come! You have to see this!” I pulled out the front-page story that Michael had found a few months earlier and laid the two papers side by side on the table. “So, this is how the story ended.” We read the stories. While our children played in the other room and her infant settled peacefully in the warmth of a Southern winter sun, we felt the weight of it sink in.

I was not surprised, but it still hurt to read the follow-up piece. Even with a preponderance of evidence and testimonies, every man on trial got away with murder. This fact was not front-page news but tucked beneath odd stories called “Flashes of Life”: A baseball fan fell asleep in the stadium, a mother cat began nursing baby rats. The short piece quoted how the defense urged the jury to resist “Northern ‘interference’ and demanded an acquittal to ‘show them it’s no use meddling in Greenville County.’” Three of the 31 men received direct acquittals, it took less than six hours for the all-white, all-male jury to acquit the other 28 who were charged with “murder, conspiracy to commit murder, and of being accessories both before and after the fact.” Perhaps most troubling was to read of the cheerful atmosphere in the courtroom as children and wives sat with their husbands as if it were a church picnic. “The acquittals set off a wave of jubilation among the defendants and their relatives.”

Later, I would read that this case was considered to be the last lynching in South Carolina. The British writer Rebecca West, who covered the Nuremburg trials covered this trial in a novella-length article for The New Yorker called “The Opera of Greenville.” Although the African American press had been covering lyncings for decades, the length and depth of this article forced both Northern and Southern white readers to reckon with the brutality of lynching and hold it in the same light as the human-rights abuses of the Nazis. In the wake of the genocidal horror of Hiroshima and the Holocaust, West was able to hold a mirror up to brutality enacted on American soil toward American citizens.

Though the trial itself was a miscarriage of justice, it marked a turn in public opinion both for South Carolina and the South. It marked the end of an era in which mob violence would go completely unchecked. And it foreshadowed the legal battles, community organizing, and public outrage that would fuel the Civil Rights Movement. The remnant of the black community who did not flee the area boycotted white Greenville cab drivers. In an attempt to rebuild shattered trust, the white cab drivers began offering free rides to church on Sunday for black patrons. The trial, its coverage, and the community response marked an important turning point in which people who once believed they could operate above reproach might be held accountable under the law and face public shame in their community.

The story of Willie Earle landed in my path, so I took some time to listen close. I listened to his mother’s voice on an oral history collection of the University of South Carolina. Her words, “They Stole Him Out of Jail,” became the title of William Gravely’s 2019 book which details all aspects of the case, the media coverage and its long-term impact on race relations and politics in the community. I found myself keeping vigil in mid-February, almost 73 years to the day of Earle’s killing on a frozen road 90 miles from my home.

After I began writing this, I decided to go look for They Stole Him Out of Jail from my local public library. I expected to look it up in the system and hunt for the book on the shelves. Instead a circle of books set aside for Black History Month greeted me beside the circulation desk, and on the top tier facing me was the face of Willie Earle. I checked it out and brought it home. My 11-year-old daughter saw me reading the book and surmised from the cover that this was a tragic tale. She asked me why they did that to him, and I told her about vengeance, hate, and inhumanity. Then she hugged the book in my hand and whispered words of comfort into Willie Earle’s ear.

“What is this all about? Why is this here?” my friend wanted to know. I have no logical explanation for why these pages of the paper landed in my yard, why the wind tore and sorted them just so, just now. I can’t explain why my library had the book ready for me before I asked. This region is saturated in stories of justice denied, racial brutality, the lies of white supremacy. They are in the air. Frederick Douglass (one of my ancestors — I’ll save that story for another day) once said, “We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and the future.” I wanted to use those old papers as mulch, to block the weeds, to trap nitrogen and amend the soil. As tempting as it is to discard them all together, to avoid the process of lament, these old painful stories have a way of finding us. They are a window into where we have been, a metric for where we are, and a call for us to press on toward a better future.

Josina Guess is the Assistant Editor of the Bitter Southerner.