When you decide to reckon with the spirit of the dead — in particular, that of Flannery O’Connor — you must also reckon with the spirit of one still very much alive, Alice Walker. A road-trip meditation on two of our greatest authors.

Story by Carly Berlin | Photographs by Amanda GreeneThe first time I went up North was also the first time I read Flannery O’Connor.

It was the summer before my final year of high school in Atlanta, and I convinced my parents to send me to a month-long creative writing program at a New England university. To me, this event marked the beginning of a life I’d fantasized: an existence in which I’d become a sophisticated Northern-intellectual writer-lady, one who wore big, enveloping scarves and walked cobblestoned streets with manuscripts in hand. It was my first chance to try New England on for size. Finally, I could see how I measured up against what I imagined to be hoards of sophisticated Northern-intellectual writer-people, all vying to release their enlightened words into the ether.

That summer, my teacher flung a story in front of us whose setting was the very place — or, at least, adjacent to the very place — I had just left. We were to read O’Connor’s “Good Country People.” In the story, a prolonged illness brings Joy Hopewell back home to her native Georgia from some unspecified “away.” Joy, a recent recipient of a philosophy doctorate, accepts her prodigal daughterhood with disgruntled entitlement.

“Joy had made it plain,” O’Connor writes, “that if it had not been for this condition, she would be far away from these red hills and good country people.” Joy’s mother, Mrs. Hopewell, does not know what to do with a daughter who has so wholly pivoted from the place she was raised. Mrs. Hopewell frets endlessly at her daughter’s choice, when Joy first moved away, to change her name: from the cheerful Joy to the “ugliest name in any language,” Hulga. With what I imagine to be a defeated shake of the head, Mrs. Hopewell laments that although her daughter may be brilliant, “she didn’t have a grain of sense.”

Much was lost to me in this first O’Connor encounter. I didn’t yet know how O’Connor had laced her own biography into Joy/Hulga’s character. I couldn’t anticipate how I’d soon hold a sliver of Joy/Hulga in myself. And yet I was — and still am — fixated by the way O’Connor subjects all her characters, all her settings, to the most unforgiving, and yet honest, eye. O’Connor has taught me something about how to see. One of my favorite quotes of hers, from an essay about the craft of writing, is this: “The writer should never be afraid of staring.”

Stare, I have, in the intervening years between that first reading and now. The staring has helped me hold up my four years at a New England college against my teenage Northern Fantasy and see the latter as both a reality and a myth, in turns. Writing now as a wearied recent graduate who has returned South, I can report that, up North, I did in fact wear scarves wrapped around my neck half a dozen times. I did traverse a cobblestone street, slick with an inch of ice underfoot.

Yet again and again I felt my fascination pulled back toward the South. There was so much to look at back home. There was — there is — an abundance of oddity to put on the page.

“What draws you to Flannery O’Connor?” my mother, who has never read O’Connor, once asked me.

It was the tail end of the summer before my last year of college, and I’d spent it at home.

It had been a season punctuated by the after-dinner walks my mother and I shared. Each evening we traced the outline of our neighborhood and remarked upon what we noticed in our most familiar of locales. We might nod to the small children playing in the sprinklers on their well-fertilized lawns, or to the spots where white hippie grandmas had wedged Black Lives Matter signs into the gravel beside their transplanted cacti. At one end of our semicircular street, when the lighting was just right, my mother and I could peer inside a neighbor’s window to see a Make America Great Again flag hanging above the television. We hypothesized that it was signed.

Here are some things to know about my mom: The first time she came to Atlanta, she was a kid, accompanying her parents on a buying trip for the family’s furniture store back in Charleston, South Carolina. They stayed at a Holiday Inn maybe a mile from where we live now. My mom brought that sentimental, apologist novel set in my hometown — Gone With the Wind — along for the ride. As she read Margaret Mitchell’s depictions of “content” enslaved people and their vengeful owners, my mom looked around her and asked her parents: “Where are the black people here?” My grandparents, Holocaust survivors from Poland who had so recently entered into an expanded definition of whiteness, had no answers for her. My mom, now, will talk about how much she tries to see everyone around her. I wonder sometimes at the limits of her sight, and of mine; how much we organize our landscape to obscure some people’s realities while making others visible. My mother has spent her whole life in the South. When she was young, she and her mother would stroll around Colonial Lake in Charleston, tracing loops upon loops together.

That August evening I scrambled for terms to describe my attraction to O’Connor to my mother. I cycled through memories of seminar discussions about narrative tension and the Southern Gothic. I thought of when one classmate so many summers ago raised her hand and said that one cannot understand O’Connor without understanding Catholicism. I do not understand Catholicism, nor O’Connor, still. But my lack of comprehension does not belie my mystification.

“Well,” I said to my mother, “I don’t really get O’Connor. But I like that she writes about things that aren’t pretty. No romantic shit. She has changed how I see things.”

My mother raised her eyebrows and nodded. “She grew up around here, right?”

“At a place called Andalusia, near Milledgeville,” I said. A professor up at college had once suggested I make the trek there during a school break. “She used to raise peacocks there, and I’ve read that there are still a few around.”

My mom paused, looking up at a telephone pole where a woodpecker made itself known. Cicadas shrouded in the trees began their nightly symphony as the air settled, thick, around us.

“Why don’t we go visit there before you leave town again?” she asked.

I smiled, slowly. “I’d love that,” I said.

“It was after a poetry reading I gave at a recently desegregated college in Georgia that someone mentioned that in 1952 Flannery O’Connor and I had lived within minutes of each other on the same Eatonton-to-Milledgeville road,” Alice Walker wrote in 1975.

Walker, the celebrated activist and author with a cutting eye to race, gender, and the South, once wrote an essay called “Beyond the Peacock: The Reconstruction of Flannery O’Connor.” In it, Walker detailed a day when she visited Andalusia with her mother, after Walker realized how near her family and O’Connor had lived to each other on Highway 441.

In college, Walker had read O’Connor incessantly, rarely thinking of the difference between O’Connor’s identity and her own. But when Walker discovered there were black writers whom she “had not been allowed to know,” she put O’Connor away and picked up Zora Neale Hurston and Nella Larson and Jean Toomer.

Years later, when Walker was living up North, she planned a trip to visit both her old home and O’Connor’s. It was 22 years after the Walkers had moved from that house and 10 years after O’Connor’s death.

“To this bit of nostalgic exploration I invited my mother,” Walker wrote, “who, curious about peacocks and abandoned houses, if not literature and writers, accepted.”

When the two arrived at their old home near Eatonton, Walker and her mother found a “No Trespassing” sign and a gate beyond which they saw only muddy pasture. While Walker hesitated with trepidation, her mother opened the gate. The two walked through pines and wild azaleas to find their old house, barely standing. The Walkers stood there, remembering.

Alice Walker’s childhood home in Eatonton, Georgia

“I remember only misery,” Walker wrote, “going to a shabby segregated school that was once the state prison and that had, on the second floor, the large circular print of the electric chair that had stood there; almost stepping on a water moccasin on my way home from carrying water to my family in the fields; losing Phoebe, my cat, because we left hurriedly and she could not be found in time.”

The only solace Walker found “in a life of nightmares about electrocutions and lost cats and the surprise appearance of snakes” was the field that stretched from her home to Milledgeville, a field that “represented beauty and unchanging peace.” Beyond the field, she realized later, was O’Connor’s place.

Wards Chapel A.M.E. Church, where Alice Walker was baptized

As my mother and I drove out of Atlanta toward Andalusia, I studied the sprawl around us. Driving out of Atlanta always looks somehow the same, no matter the direction we head. That day we saw billboards for Chick-fil-A and Coca-Cola and airlines that fly out of Hartsfield-Jackson; we saw strip malls and mega-churches; we saw subdivisions with culs-de-sac we liked to believe were more manicured than the street where we live. The sprawl has a way of confounding boundaries. It muddles the lines we’ve decided exist between neighborhoods, between regions.

When we crossed Atlanta’s perimeter highway that day, the suburbs bled into a monotony of forests and fields. My mother was more familiar with these parts than I was. She pointed out the state park where she and her sorority sisters went on a retreat once, and the shore of Lake Sinclair where she’d visited a grad school boyfriend years ago. On Highway 441, we saw one home with a big front lawn that boasted both a tableau of Peanuts characters and a Confederate battle flag on a pole planted in the ground. Somewhere around the time we began seeing signs for the “Auntie Bellum Trail,” a white billboard on stilts appeared at the edge of the trees along the road.

“Andalusia Farm: Home of Flannery O’Connor,” it read. A small plank hung below it, with red text touting a title of an O’Connor story: “The Life You Save May Be Your Own.”

Rockers on the front porch of Andalusia

We turned down a red clay road and drove through an open gate. At the end we saw a big white house with a front porch lined with rocking chairs facing a pond. We drove around back, where we saw a dry water tower and a quiet barn and an empty sharecropper’s shack. All sat far enough back from the road that we were surrounded by green.

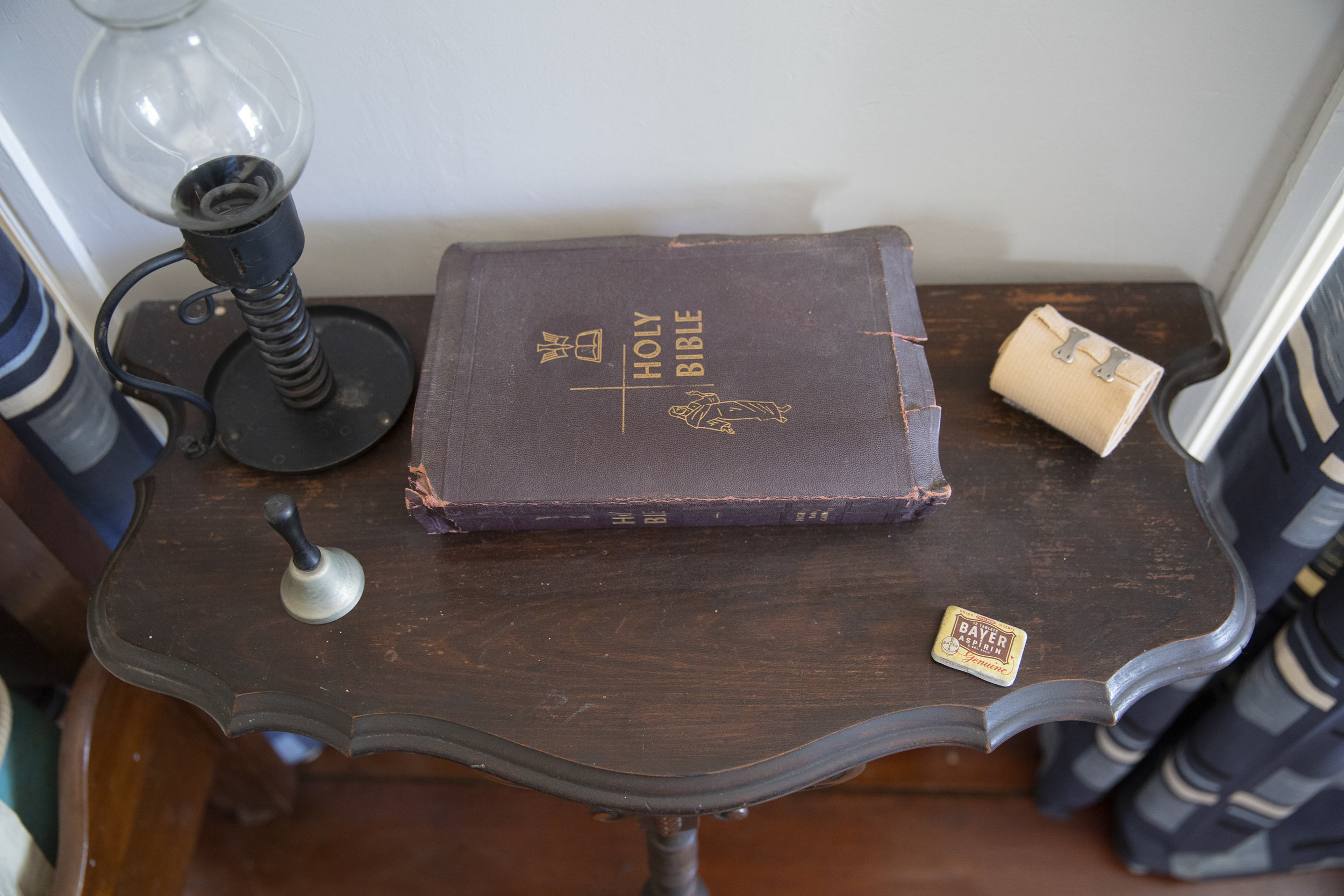

When we walked inside, we saw Flannery O’Connor’s preserved bedroom to our left. The doorway was open, but roped off. We craned our necks to peer inside. There was a double bed O’Connor had slept in, with a gold crucifix hanging on the wall beside it. There was a desk, facing inward, where O’Connor had caught the light from two windows. She had written there each morning after attending mass in town. There were her crutches, and her radio, and a fireplace. There was peeling wallpaper. It smelled like a closet that had been closed for a long time.

A docent wearing a T-shirt with a silhouette of O’Connor’s face on it greeted us cheerily and quickly launched into an O’Connor biography lesson.

“Ms. O’Connor lived here for the last 12 years of her life,” the docent told us. “She’d already gone up North to start her writing career. She got her master’s at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and was part of an artists’ colony in upstate New York. But then, in 1952, she got systemic lupus erythematosus, and she had to come home to Andalusia. Her daddy had died from lupus a few years back, and so her mama, Regina Cline, took care of her here. Flannery lived for seven years longer than they’d thought she would. Her mama helped her up and down those steps, helped her type when her arms got tired. Let her get all those damn peacocks. Flannery died when she was 39 with no kids of her own, but she raised near 100 birds. Like daughters.”

My mother and I then circled the house, separately. I paused at every marker indicating a mention in an O’Connor story. I looked up at the main barn, where I imagined Joy/Hulga stranded after the Bible salesman dupes her and steals her prosthetic leg. I pictured O’Connor standing where I was, her peacocks ambling around her, as she plotted Joy/Hulga’s demise — and envisioned her own.

Meanwhile, my mother lingered near a set of canisters that would have held sugar and salt in the kitchen. They were rounded things with silver lids.

Later, she told me, “They’re just like Mama’s.”

When Walker visited Andalusia, there was no docent, only a caretaker who looked after things. She walked up to Flannery O’Connor’s door and knocked. Walker did not think then of O’Connor’s illness, nor her writing; she likely imagined herself knocking on the door of a plantation mansion. She wrote of that moment: “It all comes back to houses. To how people live. There are rich people who own houses to live in and poor people who do not. And this is wrong. I think: I would level this country with a sweep of my hand, if I could.”

She called out the difference that race has made in the lives — and afterlives — of black and white artists. In Mississippi, there is a house museum much like Andalusia for William Faulkner, but “no one even remembers where Richard Wright lived.” This, however, was bearable to Walker.

“What comes close to being unbearable,” she wrote, “is that I know how damaging to my own psyche such injustice is. In an unjust society the soul of the sensitive person is in danger of deformity from just such weights as this. For a long time I will feel Faulkner’s house, O’Connor’s house, crushing me.”

Walker shifted to her mother, who believed that, because O’Connor died young from illness, God had shown his judgment. She said to her daughter: “Well, you know, it is true, as they say, that the grass is always greener on the other side. That is, until you find yourself over there.”

“But,” Walker replied, “grass can be greener on the other side and not be just an illusion. Grass on the other side of the fence might have good fertilizer, while grass on your side might have to grow, if it grows at all, in sand.”

As my mother and I walked back to the car at the end of our visit, we stopped at a wire enclosure near the parking lot. Two peacocks were inside it. My mother and I laced our fingers through the fencing and watched the big, weird birds hop around their cage, on this property where they had once roamed in droves.

“Let’s wait to head back until they open their tails,” my mother said. And so we waited.

Walker concluded her essay “Beyond the Peacock” with the image of a peacock preventing her and her mother from leaving Andalusia. It stood in front of their car, strutting, showing off its tail.

“Peacocks are inspiring,” Walker said to her mother, “but they don’t stop to consider they might be standing in your way.”

Walker’s mother responded: “Yes, and they’ll eat up every bloom you have, if you don’t watch out.”

The peacocks before my mother and me never unfurled their “galaxies of haloed suns,” as O’Connor liked to call them. We got back into the car and pointed ourselves toward home. We moved along a map with no sprawl, no perimeter, but a cartography only of fertilizer, of sand, of blooms. Before too long we pulled up by our front lawn, where my parents planted a red maple tree when I was born. Over the years I watched it grow. Now, it is tall enough to send long shadows in different directions.

A month after our trip to Andalusia, my whole family gathered in Charleston for my grandmother’s burial. Before the funeral service we all loitered, numbly, outside the low stone wall encircling the Jewish cemetery. While my mother made her rounds, looking each guest in the eye and thanking them for coming and withstanding the heat, one of my mother’s childhood friends walked over to me and expressed her condolences. I nodded, thanked her. She placed her hand on my shoulder.

“Carly,” she said. “You get to go so much farther than your mom did. Do you know that?”

I caught my breath, nodded again, silently. An hour later, I shoveled fresh dirt onto my grandmother’s grave, as is Jewish custom. First, I used the back of the shovel, to show reluctance, and then placed a full two scoops on top of the plain wooden casket, meant to disintegrate into the earth. I handed the shovel to the next person in line, and we all shoveled until the grave was full. Over the plot, I imagined, green grass would grow.

When I returned to New England, where fall had begun to turn the leaves gold, I recognized a depth of frustration in myself. “You get to go farther than your mom did.” Nothing could be that simple, that linear. I realized then that I can no longer accept an accruing of distance — from my mother, from home, from the South — as a metaphor for progress.

“The writer operates at a particular crossroads where time and place and eternity somehow meet,” O’Connor once wrote. “[Her] problem is to find that location.”

Growth, I think, has more to do with wading through the muddiness and the myths than it does with going far away. No small part of growing up is learning to see where you are.

Bitter Southerner contributor (and former intern) Carly Berlin was born and raised in Atlanta, Georgia. After graduating from Bowdoin College in 2018, she moved to New Orleans, Louisiana, where she is a freelance writer.

NOTES: Many of the references in this story come from Alice Walker’s essay “Beyond the Peacock: The Reconstruction of Flannery O’Connor.” Others references come from Flannery O’Connor’s story “Good Country People” and various essays by O’Connor.