We all know how to play checkers. Many fewer of us know how to play a complex version called “pool checkers,” because the game was defined in our lifetimes by small pockets of African-American men around the South. This variation on checkers turns a simple child’s game into a fierce, intellectually challenging sport with the complexity of chess. And its masters — the men who have dominated the game nationally for years — congregate almost daily in a little shotgun house in Vine City, a neighborhood just west of downtown Atlanta. Learn about and hear the voices of men — with nicknames like “Concrete” and “Iron Claw” — who made the South dominant in yet another sport. It just happens to be a sport you’ve never heard of.

Story and Audio Interviews by Stephannie Stokes

Photographs by Diwang Valdez

Think about how you play checkers. You pick up flat pieces, advance them diagonally forward, one square at a time, across the board, jumping and eliminating your opponent’s men along the way. If your piece makes it to the other end, it becomes a “king” that can move backwards. That, of course, is just to help you with your main goal, which is to rid the board of any piece not your own.

It’s simple, a game you probably learned as a kid, right?

Well, as it turns out, there’s another way to play checkers — or “draughts,” as it’s known internationally — that’s different from the game so many Americans know. It’s called “pool checkers,” and in it, all pieces, not just kings, can move backwards. And kings, for their part, in addition to moving backwards, can slide across the board several squares in a single turn, much like a queen in chess.

The greater variety in how pieces can travel the board makes this game more complex, or “more fascinating,” as its players say, than the one you might associate with childhood, which in this game you’ll hear called “straight” checkers. Many pool checkers players — who, except for the occasional Russian, happen to mostly African-American men — will argue it requires just as much strategy as chess.

It’s hard to find information about how pool checkers came to be. The game’s history has been passed down from older players to younger ones and was rarely put into writing. But most in the pool checkers community believe its origins trace back to the time of slavery. And according to a Ukrainian player, Jake Kacher, who has developed an online library about the game, that makes sense. Many Southern states were colonized by French and Spanish settlers, who played versions of draughts that were similar to pool checkers, Kacher says. English colonists, on the other hand, preferred a game more like straight checkers.

As we now know, it was the English’s game that took off nationwide, and Kacher points out that doesn’t just mean among white people — straight checkers is played by everyone. Pool checkers, however, seemed to remain mostly the domain of black men in the South.

If you want to see this alternative version of checkers played, you can visit most major cities in the South, where it has historically been popular, places like Columbia, South Carolina and Memphis, plus some areas farther north.

But to meet the game’s most skilled players, the men who dominate pool checkers year after year, you have to travel to Atlanta, to a shotgun house in Vine City, just west of downtown.

"My name is Alfred “East Point” Barnett and I’m known officially all over the checker community in this nation and the world as East Point. You can trade a lot of shots in pool checkers that you couldn’t in straight checkers, so that’s why I love it so much."

When Alfred “East Point” Barnett was growing up in the 1950s and ’60s, you didn’t have to go far to find a good pool checkers game in Atlanta.

It was a popular pastime. Old men, as they almost always were, would set up boards in barber shops, on someone’s porch, under a “shade tree” — any place where two people could find seats. That was the beauty of checkers. In a pinch, you didn’t even need actual pieces. Soda caps would do just fine.

Like many pool checkers players, Barnett started playing the game in the public housing complex where he grew up in East Point, Georgia, just south of Atlanta. He caught on so fast that he came to believe it was an ability given from God, or his mother; he’s heard that she, while pregnant with him, was glued to the checkerboard.

Now at 67 years old, Barrett is a legend in the game. Over the last two decades, he’s won 12 national tournaments, securing his latest title earlier this year. And this last one was important, too. It established him as the most decorated player on the books in pool checkers, a board game that’s captivated him for more than 50 years.

“Been playing pool checkers since I got started, that was in the fifth grade,” he says. “I never strayed away from it. I have played straight checkers, but never caught on too good with it. It interfered with my pool checkers ability.”

At 6 feet 6 inches tall, Barnett was an athletic teenager, later training to play basketball professionally, but he always made time for checkers (with the exception of a year or two spent at the University of Colorado, where he received a full basketball scholarship; to his dismay, there were no pool checkers players there). For hours, back in East Point, he would battle other players in the projects, sometimes in the basement of a man named George Few, otherwise in a parking lot outside.

Eventually, he grew to be a good player, so good that he exhausted the men in his neighborhood. Needing new competition, Barnett made his way up to Atlanta. He wound up at the newly formed Georgia Pool Checkers Association, on the corner of Griffin Street and what is now Martin Luther King Jr. Drive in Vine City, just down the street from Atlanta’s hub of historically black colleges and universities.

Inside the club too, it was mostly old men, Barnett remembers. The first time he dropped in, he says he surprised them all by winning several games from the start. They asked him, only 19 years old then, where he was from, and forgot about his name. From then on, they just called him "East Point."

"My name is George Few, but they call me Concrete at the club, they call me Concrete. I’ve been playing for years. I tell them down at the checker club, I’ve been playing this stuff for over 70 years. You know, y’all gonna start up and go beat me. No, there ain’t no way."

The Georgia Pool Checkers Association in Vine City started with a larger movement to turn pool checkers into an organized game, like straight checkers and chess. Before then, players around the South and those who played in cities farther up the East Coast had little contact with each other, and often, as a result, the rules of pool checkers would change depending on your location.

The formation of a national organization, called the American Pool Checkers Association, in the mid-’60s standardized the game and gave players an opportunity to compete with each other in tournaments. To join, players in various cities started their own local chapters. The Atlanta club was the first.

The initial meeting place was just a garage on the same Vine City corner where the clubhouse is today. While the garage is no longer there, that’s where the checkerboards were set up when George “Concrete” Few started coming around.

Learning the game as a teenager, Few, now in his 80s, has a longer history with pool checkers than perhaps anyone else at the club. Today, glaucoma impairs Few’s ability to play competitively, but in his prime, he could easily hold his own. That’s when he earned his nickname, which is often the mark of a good player. He became “Concrete” because, as he says, “You got to be hard to play checkers.” Maybe it helped that he was also a brickmason.

Before making his way over to the checkers club, Few would play with other men from his East Point neighborhood, including a young Barnett, in the basement of his home, which he built specifically with checkers in mind. Few says he could spend all night down there with his friends and their checkerboards, and since he’d never technically left the house, his wife couldn’t complain. But the checkers club provided a different kind of opportunity; it was a chance to compete against men from all around Atlanta.

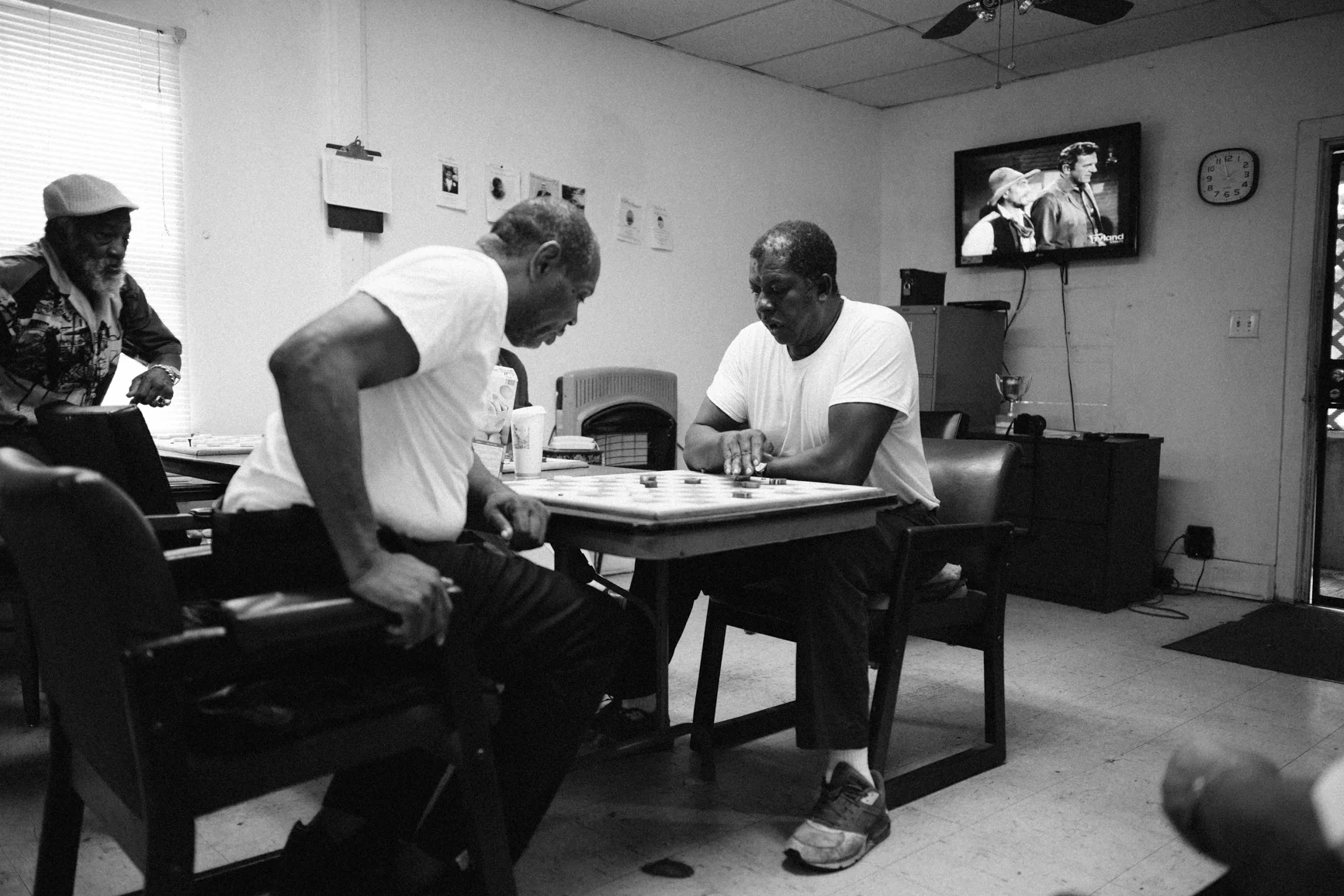

Once the club really got going, in the 1970s and ’80s, Few remembers it was an exciting place to be. On any given afternoon, you’d find the local reverends, postal workers and police officers, as well as coaches and educators, packed into a single-room home, which one member eventually helped buy for the club — as an upgrade from the garage.

You’d hear pieces slamming against the board, as players yelled and talked trash, probably using one of the two most common insults in pool checkers, “sucker” and “ham.” Occasionally they’d set up a few checkerboards out in the yard to accommodate more players. And even then, there might still be a line — lose a couple games and you would have to forfeit your place to the next player.

The members weren’t playing for money, at least not for much. Club rules required losers to buy cookies and sodas for the group, or sometimes put a dollar in a jar. Perhaps the most valuable part of winning was earning bragging rights — the ability to say you “mugged” someone. Few still treasures the memory of a particular match, in which he beat an already competitive Barnett five games in a row, or “five straights.”

“It’s still in the record book,” Few says. “George Washington been dead over years, and they still reads about him. That’s right, I’m in the record book on him. I get him five straights. He can’t erase that.”

"OK, my name is Michael Jordan, and I’ve been playing at least 60 years. I have played all night long. We’d start playing that evening and be there at morning and then we’d be trying to go to breakfast. I guess you could say we were a little crazy. That’s how much we loved to play."

For many members of the Georgia Pool Checkers Association, pool checkers was a fun hobby. It was a way to escape from the stresses of work and family. But as some players went to the annual national tournaments, in Memphis, in Houston or in St. Louis, and competed against others from around the country, they became more serious about the board game.

They developed a “scientific” approach, as some players call it, advancing their knowledge of the game by challenging better players and picking up the few books written about pool checkers. Barnett was one of these players, and so was Michael Jordan, who has been with the club since the beginning.

“There was, I guess you could say, guys that had potential to play checkers good,” Jordan says. “We were kind of the new prospects coming along.”

Jordan grew up in Pittsburgh, the Southwest Atlanta neighborhood named for its industrial history, and learned checkers from the old men who crowded over a single checkerboard in a shoe shop on MacDaniels Street. He joined the Georgia Pool Checkers Association in his mid-20s, making time for checkers on the days when he wasn’t driving to Jacksonville for Greyhound.

Despite not having a nickname — probably because, with a name like Michael Jordan, you don’t really need one — he has established himself as a skilled player, known in particular for a series of moves called “pitch and squeeze.” With a full-time job, Jordan never had time to study, but he learned by playing those who did, and he said most people don’t realize the kind of strategy that goes into a competitive game of pool checkers. A good player keeps a log of moves, tactics and maybe all of the games he’s played, either on paper or in his head, because a good player won’t lose the same way twice.

“There are certain spots on the board that you’re not supposed to give up,” Jordan says. “You have like, defensive spot, offensive spot, and if you’re not really into it, you don’t even know what I’m talking about. It really is a challenge, challenge your mind. You would really need to get into it to really understand the game. It’s not just a game that you see a lot of old people playing out under the tree. It’s a much deeper game than that.”

As players like Jordan immersed themselves in pool checkers, they started making names for themselves. The tournaments that had long been dominated by Chicago, and its legendary player Carl “Buster” Smith, soon became Atlanta’s territory. From the mid-’90s on, the first-place title went either to Barnett or to another Atlanta player, Calvin “Iron Claw” Monroe. At one championship, Atlanta players took home all top three prizes, with Michael Jordan receiving third place — still his best record.

But the city’s new reputation in the game earned no notice outside the small pool-checkers community. Even as the Atlanta players’ wins piled up, they received little mainstream attention. They certainly weren’t household names, like chess champion Bobby Fischer. Most Americans didn’t even know their game existed.

"My name is Calvin Monroe. Most checker players have a nickname, but my nickname is Iron Claw, I-R-O-N-C-L-A-W. I have been playing checkers, scientific checkers, ever since 1980, so if you do the math it’s quite a while, and I’ve enjoyed it. Checkers is time-consuming, it’s different than any other thing. Some people have checkers in their blood."

Why pool checkers has remained so obscure in American culture is something that its players have long struggled to understand.

“I don’t think it has the attention or the notoriety that it should be given, because it’s such a great game, and a beautiful game,” says Calvin “Iron Claw” Monroe. “And people are so serious. You see how serious they are. They’re very serious about the game.”

Monroe is the one player who rivals Barnett on the checkerboard, and he has the championship titles to prove it. Originally from Anniston, Alabama, Monroe left his home to work as a firefighter for the city of Atlanta, and he joined the Georgia Pool Checkers Association in the ’80s as a way to get his mind off the disturbing scenes he witnessed on the job. The closest Monroe, generally a polite and soft-spoken man, comes to resembling his nickname, “Iron Claw,” is during a competitive game. His face becomes stern and focused as he thinks long and hard about each move, sometimes to the frustration of other players, since his slow pace can make a single game against him last upwards of an hour.

Some players think it’s a mind trick that he might have learned from a famous Russian checkers player, Vladimir Kaplan, who became Monroe’s mentor. The strange thing about pool checkers is that, despite its obscurity in the U.S., it is apparently taken very seriously in parts of Europe, especially countries formerly in the Soviet Union. For that reason, Eastern European immigrants have participated in American pool checkers tournaments in the past, and in some cases even joined clubs. Often they became sources of inspiration for players, as Kaplan was for Monroe.

“Russians have led the way with chess and checkers, in other words playing it scientifically, and then studying it, like arithmetic in school,” Monroe says. “In the South, players were just playing checkers. They didn’t have any scientific knowledge. It was just a foreign thing to do.”

In Russia, checkers doesn’t have the image problem it does in the U.S. Most people here, Monroe recognizes are probably only familiar with straight checkers and write off the game as simple, a lesser cousin of chess. Monroe believes this is just a reflection of the money associated with the game in the U.S, rather than any indicator of its complexity. Unlike chess, he says, pool checkers has never been of interest to wealthy people, and so it never received the same recognition.

There was hope once, when one of the Russian players won a pool checkers tournament, that would change, that sponsors might finally buy into the tournament and boost the winning pot. Right now, pool checkers winnings hover around $1,000, which, compared to the $60,000 prizes at national chess tournaments, isn’t much to brag about, and sometimes isn’t even enough to entice players to make the trip to the tournament. But that was decades ago now. Russians rarely come to tournaments anymore, and the money never did come.

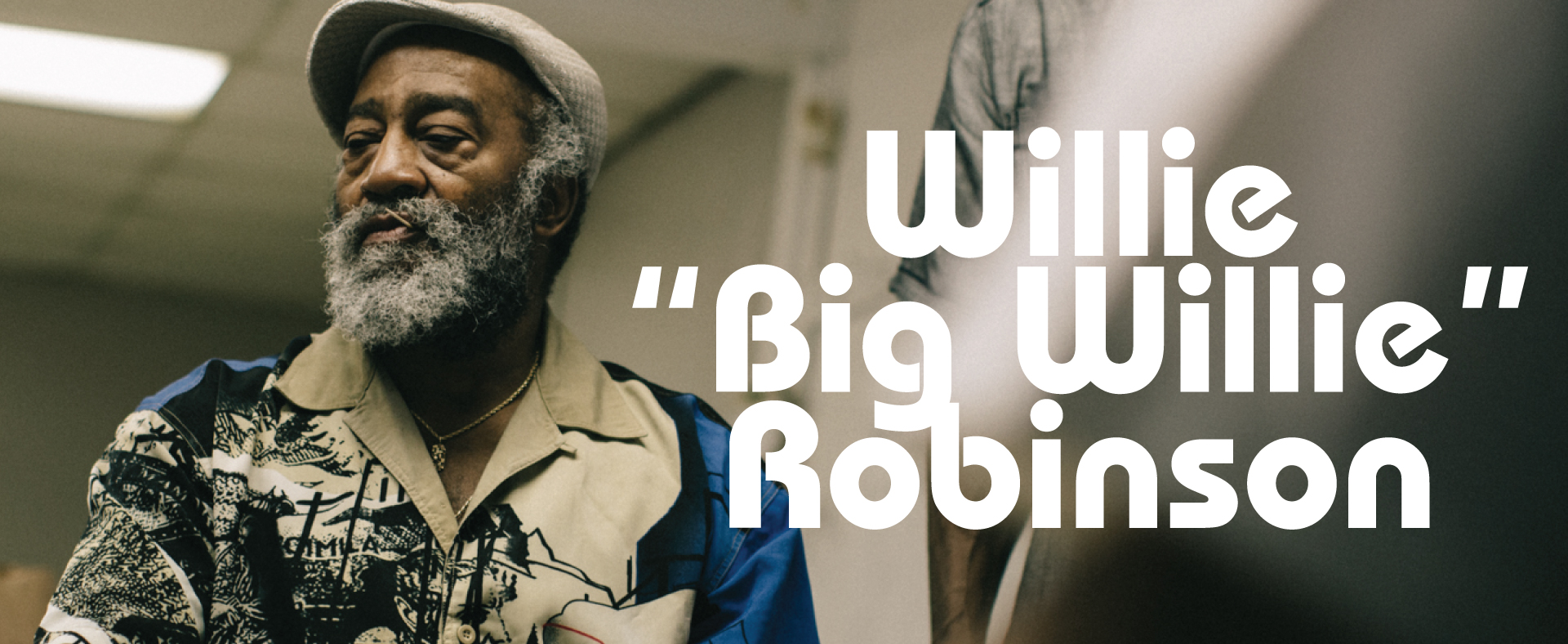

"My name is Willie Robinson. The best thing that probably ever happened to me was when I started playing checkers. When I’m over here, I forget about home sometimes. I’ve had so much fun doing this. If I could go do it all over again, I would probably do it about the same way."

Now players say pool checkers is just dying away. Fewer people show up each year for tournaments, and the number of local clubs affiliated with the American Pool Checkers Association is half what it used to be. Among those that dropped the designation was the very first to join, Atlanta’s club in Vine City, the Georgia Pool Checkers Association.

The members still open the club just about every afternoon. Inside the club’s one open room are a couple of vending machines off to the side, a flat screen TV on the wall, and four or five worn checkerboards spread out on a couple of tables. In front of one of the boards, you’ll almost always find Big Willie Robinson.

Robinson first popped his head in the club’s door about 25 years ago and saw with surprise that men were playing checkers indoors; growing up in Atlanta’s Mechanicsville neighborhood, in a public housing unit later demolished for mass-transit construction, he’d seen it played only ever out in the yard.

He kept coming back, at one point because a woman he loved wanted him out of her hair. He went to the club to give her space but it worked maybe a little too well. Playing checkers is now part of Robinson’s daily routine. Some of the other men claim it’s all he does.

“I’m here every day. I’m like the gatekeeper. I own the club,” says Robinson. “So I just put my time in, just like hitting the time clock.”

Other members confirm that Robinson’s time spent at the club has paid off — he’s a challenge to beat on a checkerboard. But unlike the other top players, he hasn’t left Atlanta to prove himself at the national tournaments. His view of the game comes mostly from what he sees in Atlanta and at the Georgia Pool Checkers Association. And inside the club, even over the last couple of decades, Robinson has watched the membership rolls dwindle.

Pinned to the walls now are a series of programs, taken from the funerals of former members. One shows the picture of their last president, who died back in 2013 and still hasn’t been replaced. In fact, few of the players who passed away have had their spots filled by new recruits. The club has just a dozen members left, mostly retired men in their 60s and 70s, with at least one in his 90s. That might be why when you Google the club now, it comes up as a senior citizens’ center.

And as the checkers players age, the neighborhood around them is changing. The new Atlanta Falcons stadium is under construction a few blocks away, and hotels will soon rise up around it. Still, Robinson says he can’t imagine the Georgia Pool Checker Association members shuttering their shotgun house on Griffin Street.

“We’ll probably have a handful of members, probably count ’em on your foots and toes,” says Robinson. “We don’t want the club to go. A lot of them old, we’re just gonna grow old in the club and die in the club. I hate to bring it up like that, but that’s how much we are attached to one another and the club.”

Pool checkers players use different theories to explain why fewer people are taking interest in the boardgame. One blames computers and the Internet for providing young people instant gratification. All the men admit it can take some practice before checkers really becomes interesting.

Another explanation, however, connects the decline of pool checkers to something that was developing much earlier, to a shift in economic opportunities for African-Americans in the South. One person who holds to this idea is the East Point man who ended up devoting much of his life to the game, Alfred Barnett. He believes it was when new doors were opened, for the generation after him, that checkers started fading.

“Black people got better jobs, and people that didn’t work for much money began to make money, they could do a little bit more. They moved from East Point to Atlanta to get out of the projects and into homes,” says Barnett. “They wanted to get better jobs, better opportunity for their kids, and checkers wasn’t part of it.”

Pool checkers only stuck around over the years, Barnett says, because certain people wouldn’t let it go, players like himself and Jordan and Monroe at the Georgia Pool Checkers Association.

When he joined the club all those decades ago, Barnett was a young man learning from the old players, and he believed the game had a chance of growing, maybe into something like it is abroad, where championships are covered on television and prizes are equivalent to a decent salary. As he’s grown old, he’s realized otherwise.

“You can’t believe in something that ain’t gonna be,” Barnett says. “You go on with your life. It’s not like tennis, baseball, so many different things. It definitely don’t compare with chess. I thought that one time, but I made a mistake.”

Barnett will keep playing, although maybe not in tournaments. He may just remain a 12-time national champion, whose name nobody knows.