Wayne’s World

This is the story of how a weird Tennessee comic-book nerd went to New York and created “Pee Wee’s Playhouse,” then went to L.A. and conquered the world of fine art. He did it by doing two things the art world isn’t very comfortable with — being funny and being Southern.

Southern fact you did not know: Without President Jimmy Carter, “Pee Wee’s Playhouse” would not have been as magical.

When President Jimmy Carter was inaugurated in January of 1977, the unemployment rate was high — 7.5 percent. Carter successfully pushed Congress to pass an economic stimulus package that included $8 billion to expand programs under the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, which President Richard Nixon signed into law to train workers for jobs in public service or at nonprofit institutions.

Under Carter, public-service jobs more than doubled in a year to 725,000. We’ll leave the economists and historians to parse the effects of the program. We are concerned with only one of those 725,000: a job at the Cumberland Museum and Science Center (now known as the Adventure Science Center) in Nashville.

With CETA money, the Cumberland Museum was able to hire an exhibition designer in 1980. The museum chose a young man named Wayne White from Hixson, Tenn., a community on the Tennessee River just north of Chattanooga. White had freshly graduated from Middle Tennessee State University with a degree in painting.

“I came out of school a painting major with all this snobbery about fine art and commercial art. I got that beat out of me quick the minute I got in the real world,” White says today. “I mean, I was a fucking painting major in Nashville, Tenn., in 1980. There was nothing. Nothing. I needed a job. They had the CETA program there at the museum and they had an opening. I owe Jimmy Carter my first art job.”

Six years later, in New York City, Wayne White joined the team that would create the mad world we knew as “Pee Wee’s Playhouse.” He designed sets, built puppets, and created and voiced characters like Randy the juvenile delinquent marionette. White and his colleagues burned madcap psychedelia into the brains of every child who grew up in the late 1980s — not to mention the stoner college students and 20-somethings who, no matter how late they’d been out on Friday night, somehow managed to plant themselves in front of the television every Saturday morning at 9:30 so they could visit the Playhouse of their dreams.

It was one of the greatest tricks ever pulled on network television.

Thank you, Mr. President.

Wayne and his dog, Mabel, in his Los Angeles studio.

There are many reasons more people in the world should know who Wayne White is. Here are three:

He is a Southern boy made good (whatever that means), which is a topic we will explore in a minute or two with Wayne himself.

He realized from the moment he left Nashville and headed for New York that he would be forced to play the role of “designated Southerner” in any crowd. But unlike many of us in similar situations, he didn’t try to back off on the drawl. He just was what he was — a weird Tennessee painter and comics nerd — and in the downtown New York art crowd of the early 1980s, being a Southerner and being yourself took guts.

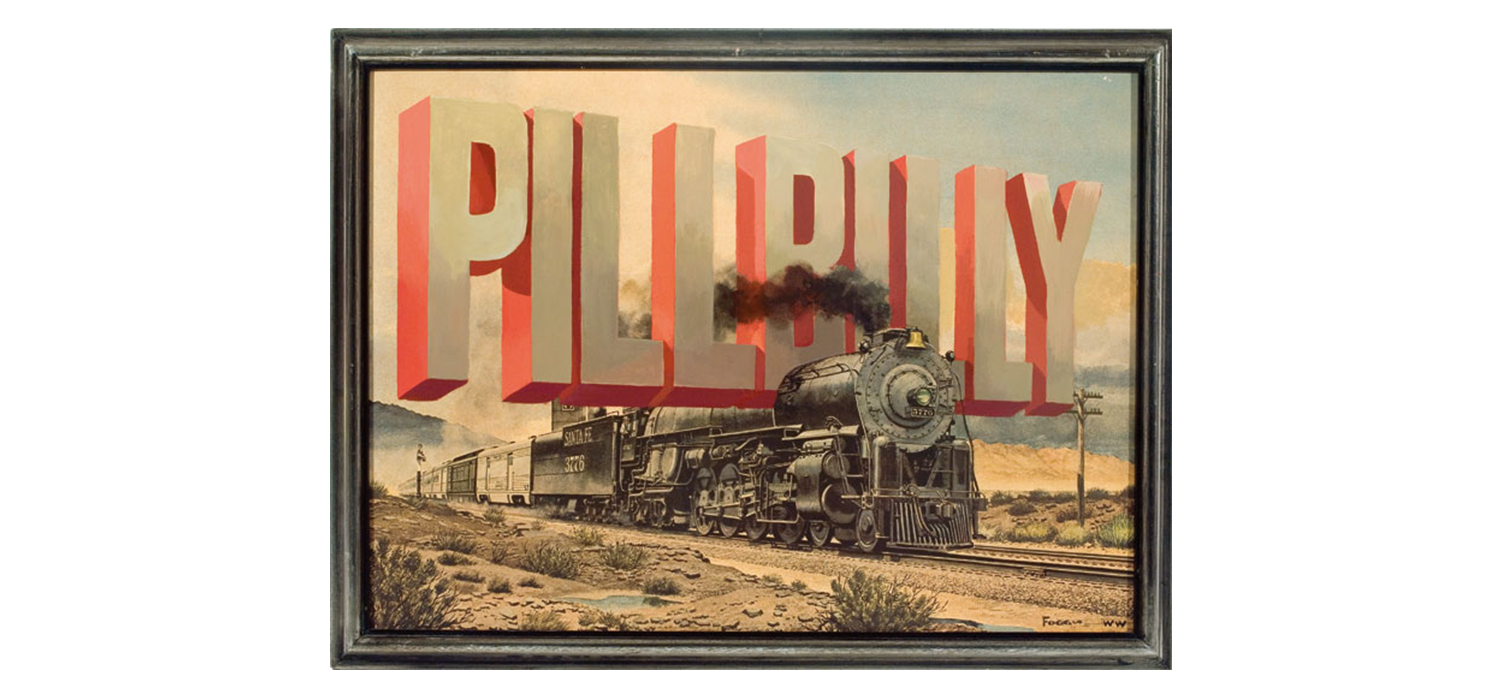

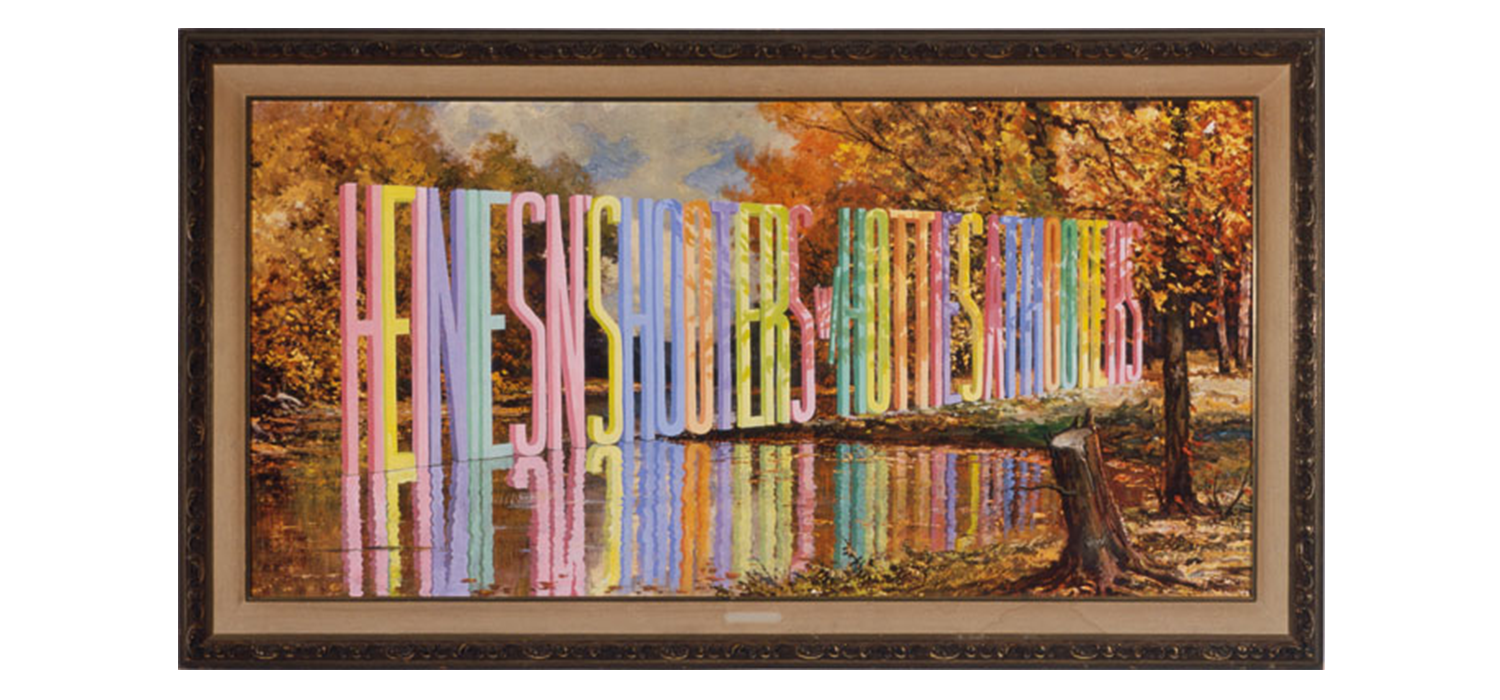

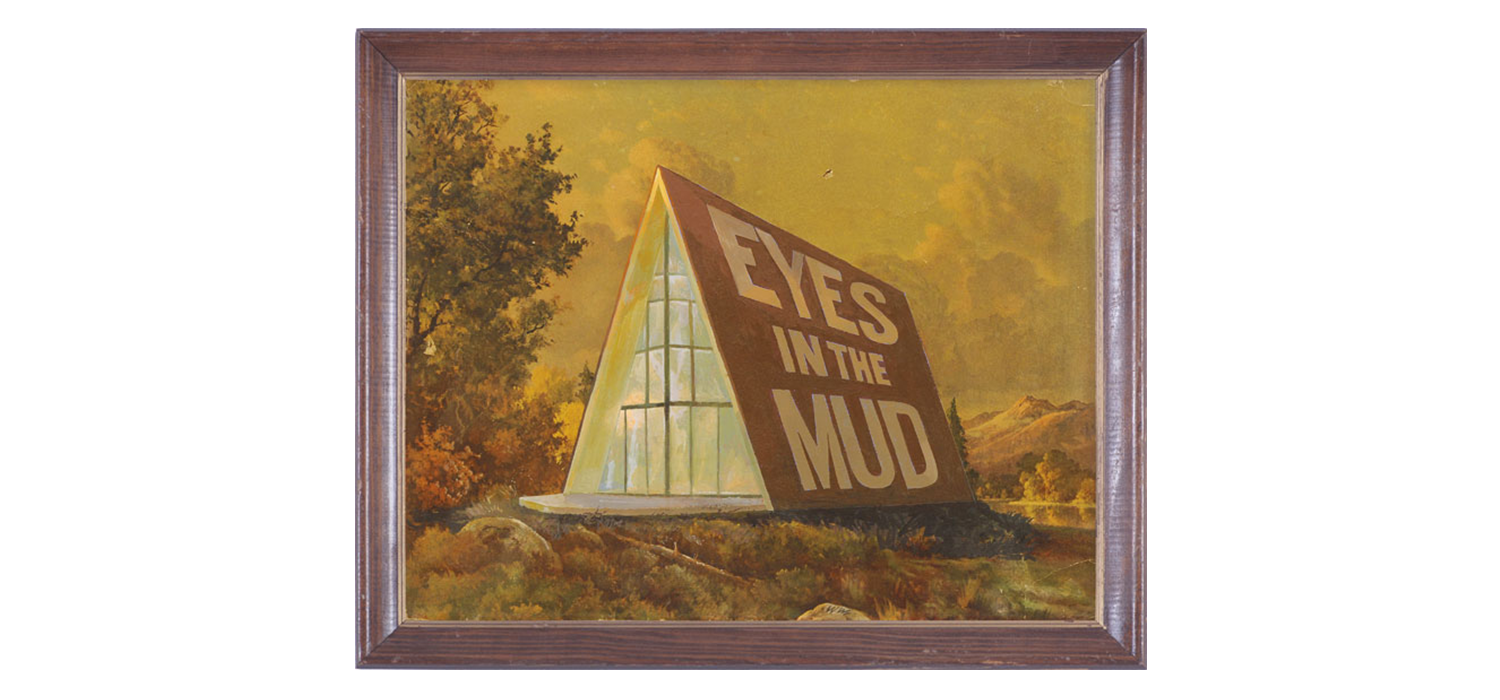

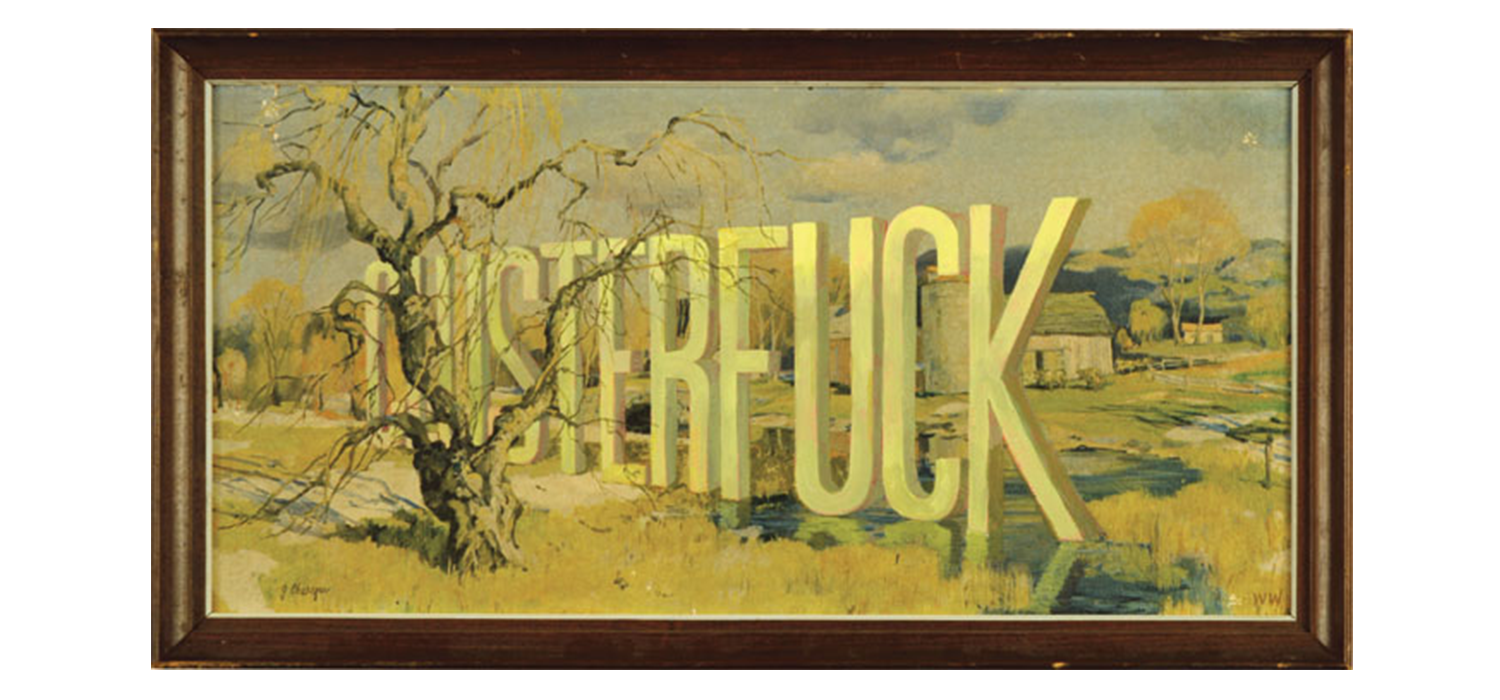

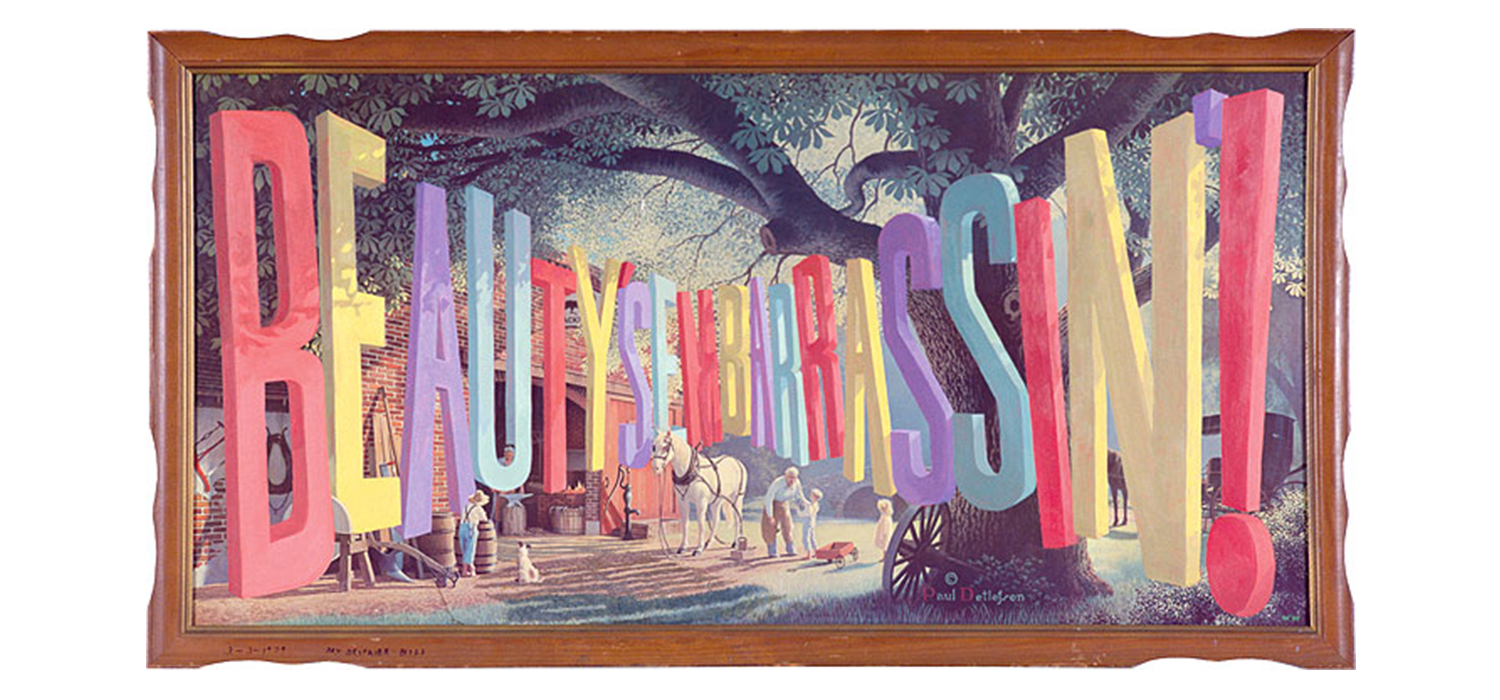

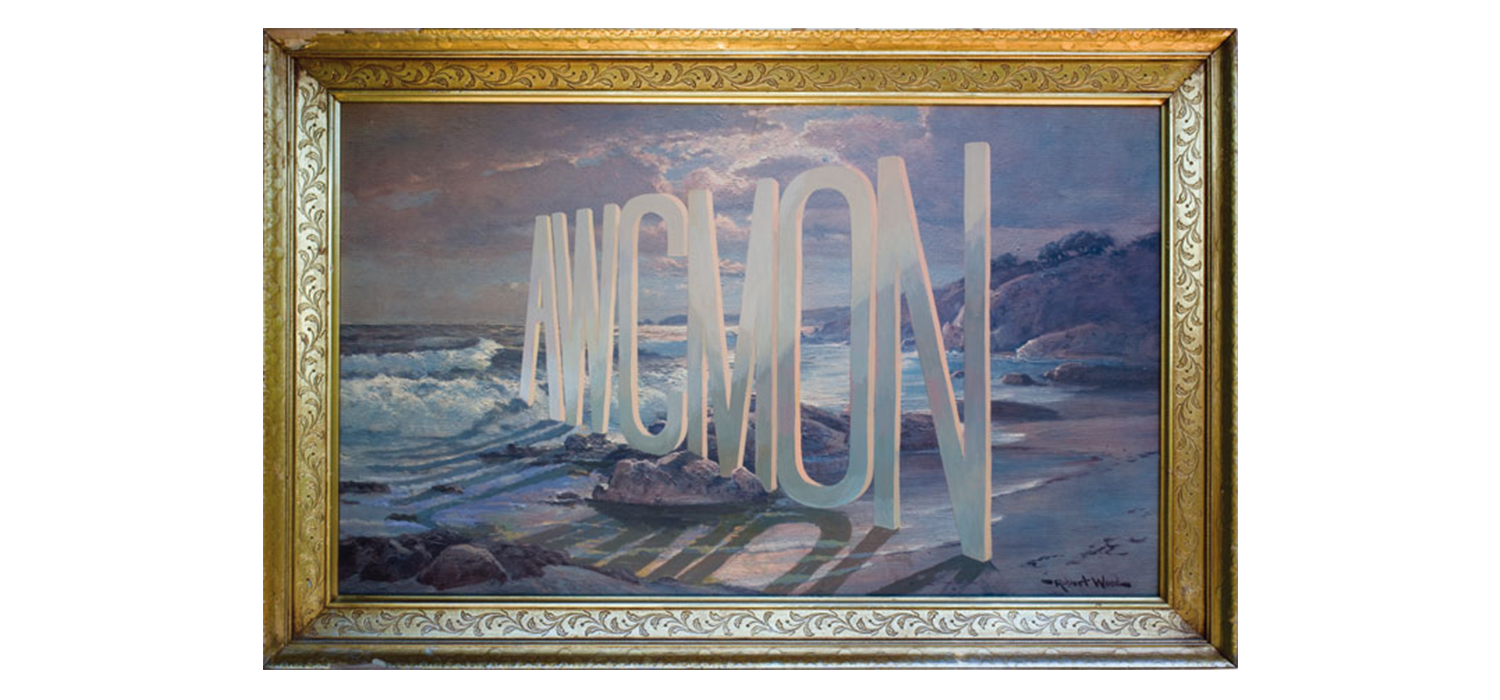

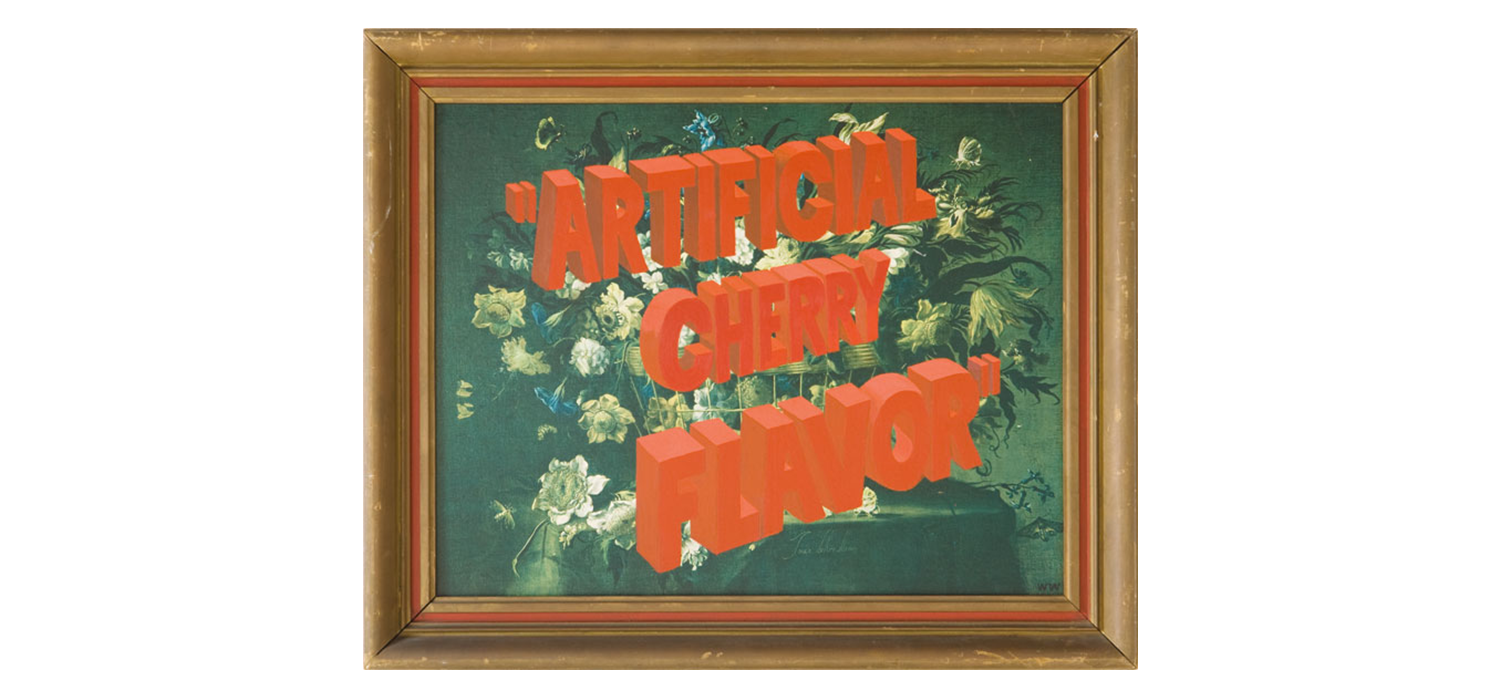

With his current creations in Los Angeles, his “word paintings” in particular, he is doing something no reasonable person would think doable: He is shoving humor — not that sly intellectual stuff, but bawdy Southern laughter — into the art world, a scene which, at least among the highest and mightiest collectors, seems downright allergic to belly laughs. You say this is undoable? Well, do you think you could buy an old framed landscape from a junk shop and paint words that look like monumental sculptures directly onto it, saying things like: “Heinies ’n’ and Shooters w/ Hotties at Hooters”? And then do you think you could sell that to an art collector for thousands?

No, you couldn’t.

But Wayne White can. One of his works on a junk-shop landscape, “Advertisement for Myself,” boasts:

Just a picture

Shunned by scholars

Now it costs

Ten thousand dollars.

That’s about as badass as it gets.

Drawing is Wayne White’s first memory.

I learned this by watching “Beauty Is Embarrassing,” a 2012 documentary about White by L.A. filmmaker Neil Berkeley. If you can get through the first scenes in which Berkeley interviews Wayne’s parents, Willis and Billie June White, without thinking the word “sweet,” you have a cold, cold heart.

“He always wanted to draw,” Willis says to the camera. “That’s about all he ever wanted to do. We’d buy him big old thick tablets and he’d just sit down and just draw until he drew up all the pages, then he’d turn over and draw the other side."

Adds Billie June: “Wayne was drawing before he could sit alone good.”

That talent took him to MTSU and then, thanks to the aforementioned president, he was hired for a project at the Cumberland Museum called the Curiosity Corner for Children.

“This was back when museums all were on the interactive kick,” White says. “The Exploratorium in San Francisco had started this whole new trend in education in museums — making playground-type things. We were doing our own little kiddie land, which was very Playhouse-like actually. It had an old-timey general store. A Japanese tea house. A tree house and a spaceship. All these different environments. It was a really fun job actually. I set about designing that whole area. Structures. Murals. Everything. I had a real productive year there in Nashville. That's where it really dawned on me that I could make a living in commercial art and specifically as a cartoonist.”

At the same time, he discovered Raw magazine. “That brought it all together,” he says. “It was like an abstract expressionist comic book.”

Raw was one of the most iconic alternative magazines of the time — an annual comics anthology edited by François Mouly and Art Spiegelman. Spiegelman went on to publish a remarkable graphic novel, “Maus,” which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992. “Maus” is Spiegelman’s account of his relationship with his Holocaust-survivor father, and it chillingly portrays Nazis as cats, Jews as mice and ethnic Poles as pigs.

But back in the early 1980s, Spiegelman was editing Raw and teaching at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan. When White moved to New York City, permanently, in 1982, he managed to meet Spiegelman. For a young cartoonist who wasn’t even attending SVA, this was no small feat. I ask White how he pulled it off.

“I just stalked him,” White says, then laughs. “I had read in this thing called the Comics Journal that he taught at SVA. So I went to SVA and hung around in the hallways until I saw him. I introduced myself, showed him my crappy portfolio and he let me sit in on his class, just free. Illegally. He was probably doing it just to get me off his back, but I thought, that's a real confirmation, you know?”

White parlayed his short-order experience at a Chattanooga IHOP into a job cooking at the Empire Diner in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood. He worked the graveyard shift, turning out omelettes and burgers, and spent the days soaking up Spiegelman’s class.

“I sort of flunked out of his class,” White says. “I didn't do the final project because I was so overworked and crazy. It wasn't a good schedule. I kind of wound up pissing him off actually because I didn't do the work. It was kind of a failure for me there at SVA.

“But I was learning. I was hanging around Art and I got to go to his studio. This is when he was drawing ‘Maus.’ I got to watch him make it. I got to see it in progress. It was all an education. I always say, go somewhere where everybody's better than you. That's a real learning experience. That'll put a fire under your ass. I thought I was hot shit in Tennessee but now I was low man on the pole in the big city.”

It took him three more years before the East Village Eye, an alternative paper, published one of his comic strips.

“I was just on the verge of moving back to Nashville,” he says. “I thought, well, I'm just going to live in Nashville. I just can't take it anymore. I was really feeling sorry for myself. Then lo and behold, I had been printing these little Xerox comic books and one of my characters got the attention of the editor of the East Village Eye.”

But it wasn’t the comics that took him to the big time.

It was the puppets.

Downtown Manhattan in the mid-1980s was full of tiny art galleries and performance spaces that offered every kind of show imaginable — from punk rock to performance art. Wayne White dove into that world, presenting what he calls “guerilla puppet shows” at art galleries and in people’s apartments. His shows were of the moment, very much in the punk aesthetic, with puppets copulating and vomiting and shouting streams of obscenities.

Those weird little puppet shows changed White’s life forever, in two ways. The first was romantic in nature. At one of the shows, he met his future wife, Mimi Pond, a far more prominent cartoonist than White, whose work was appearing in the Village Voice and all sorts of magazines at the time. (She also wrote the very first episode of “The Simpsons,” but that’s another story entirely.) They’ve been together now for more than 30 years, and they’ve raised two children, Woodrow and Lulu, who are both, of course, artists.

The second way punk-rock puppeteering changed White’s life happened thanks to a friend in Nashville. We’ll just let Wayne tell the story in his own words. He is, after all, pretty good at storytelling.

By the summer of ’85, I was living with Mimi, and I was getting work, and I was supporting myself. My friend Alison Mork down in Nashville, who I met at the museum, had gotten a new job at the local PBS station, WDCN, Channel 8. They wanted to do a 15-minute kids’ show, no commercials of course, that they would show the first graders to teach them music. Little simple songs. It was funded by the Nashville Public School System.

Alison said, “Why don't you show them your puppet show?” I thought, no way I'm going to get a job in the Bible Belt showing them my punk-rock puppet shows. Luckily for me there was a really cool young guy there in his early 30s, a Vietnam vet, Steve Kopels. He was up for anything, was hip to everything. He had somehow wound up in Nashville as a TV director. He loved my stuff so he championed me and hired me. I went down in September of ’85 to Nashville and started work on this music kiddie show called “Mrs. Cabobble's Caboose.”

All fall I built this whole set, built all the puppets. I knew it was my chance to up my game with this puppet thing and make it professional. I loved doing it. I loved it because it brought everything together. Building puppets and sets was like sculpture, painting, storytelling. Even cartooning was in there.

I loved situations where you could mix it all together like that. You could take one genre into another genre. I just loved that. I knew that was what I needed to do instead of just specializing in drawings. I knew I wanted to expand like that. I instinctively knew this was my shot to become a professional set designer, a puppeteer.

Sure enough I finished it up. I even puppeteered on a few of the original shows, but I didn't have time to stay for the rest of the series. I needed to get back to New York. In January of ’86 I went back to New York with my “Mrs. Cabobble's Caboose” portfolio and I heard that they were going to be doing a Pee Wee Herman show on TV. He already was a huge star by then. “Pee Wee's Big Adventure” was a giant hit. Everybody loved it. I loved it.

I heard through the grapevine that a place called Broadcast Arts over on lower Broadway was going to produce the show in New York City. They were the hottest production company going at the time. They did all the original MTV logos — anything hip on TV, they were doing it. They got the Pee Wee contract, and I took my “Mrs. Cabobble's Caboose” portfolio over there to show them and it was perfect. They hired me.

That changed my life completely. No more cartooning and illustrating. Suddenly I was a professional set designer, puppet maker and to my complete surprise a performer on the show as a puppeteer. I didn't expect that. I got a Screen Actors Guild card. Started making some serious dough. The rest is history, as they say. I was suddenly in show biz.

“Pee Wee’s Playhouse” ran for four seasons, and won 12 of the 15 Emmy Awards for which it was nominated. White got one for art direction, set decoration and scenic design.

“It was fantastic,” White says of his years working in the Playhouse. “It was a dream. Just to be in the center of the world's attention like that working as an artist. I always say it was just like a downtown New York art project that happened to get on TV. It was that. That's its power. That's why it was so distinctive. It really was something new under the sun as far as kids’ TV — or even TV in general.

“There's never been another situation like that for me,” he continues. “Not even close. Close, but not like that, not that perfect storm. To be sentimental and clichéd, it was a dream job. It really was.”

The first season of “Pee Wee’s Playhouse” was created in a Manhattan loft dubbed a “sweatshop” by everyone who worked on the show. After the first season became a hit, production moved to more professional quarters in Los Angeles.

That’s what took Wayne and Mimi to California, where they’ve been permanently planted, raising a family, since 1990.

After creator Paul Reubens pulled the plug on “Pee Wee’s Playhouse” in 1990, White’s work remained much in demand in Los Angeles. He was creating backdrops, puppets and animations for television commercials and music videos, including his fanciful, steampunks-on-Mars production for the Smashing Pumpkins’ “Tonight, Tonight” in 1995. This creation won the MTV Music Video Award for best music video.

But five years earlier, White had quietly returned to painting, in a studio at his house in L.A.

“I worked almost 10 years in the studio, just in secret practically,” he says. “I had a studio all through the ’90s. I knew it was going to take me a while to get something going. Ten long years, I painted on the side in secret while I was doing kid shows and commercials and stuff in L.A.

“I was intimidated by the art world,” he continues. “I was afraid to show anybody my stuff because I felt like I wouldn't be taken seriously because I was from the world of kiddie television. I just bided my time, and then in ’99 I showed my word paintings to Cliff Benjamin here in L.A. He had a gallery and he gave me my first show around that time, ’99 or 2000, somewhere in there. That's how I got into the art world.”

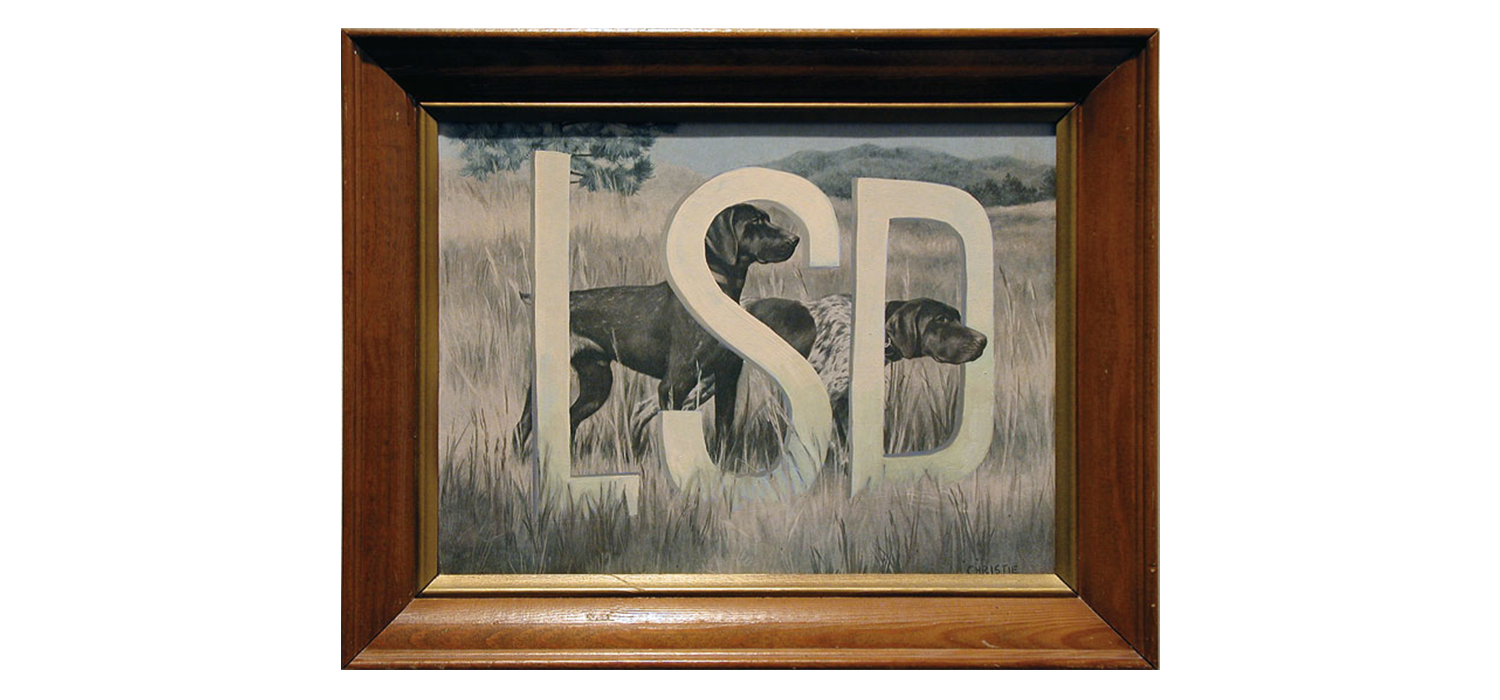

The first painting he sold bore these words: "HUMAN FUCKIN KNOWLEDGE."

It did not take long for his work to be taken seriously, and today, White’s paintings are included in the collections of some of the most prominent art buyers in both L.A. and New York.

“The whole trip of the art world is to get collectors interested in you,” he says. “They run the art world, collectors. That's who galleries all kowtow to. That's the whole shooting match. Serious collectors, not just one-time art buyers. I got a few famous collectors interested in my work, and that's what really sealed the deal for me. Like a lot of things, art is monkey see, monkey do. Once you're sanctified by these collectors, everybody else wants in on it, too.”

Which means that for the last 14 years or so, White has had the luxury of picking which projects to do. He does not, he says, have “fuck-you money,” but he loves the luxury of not having to take commercial projects just to keep the family afloat.

“I get to turn them down now, which is a really incredible, delicious feeling,” White says, and laughs heartily. “Yes, I love that.”

His life today is shaping up like the career of one of his art-world heroes, Red Grooms, a Nashville native who made it big in the art world with his gigantic, whimsical multimedia constructions. Thirty-five years ago, during his very first summer in New York, White stalked Grooms in much the same way he stalked Spiegelman. He learned Grooms had been hired to create a giant sculpture called “The Shootout” for the Denver Art Museum, so White bought the cheapest available Amtrak ticket to Denver — three days, no sleeper car — and wound up among the young artists who helped Grooms put the assembly together.

“I've always looked for a good boss,” White says. “Red, Art Spiegelman, Pee Wee Herman. People that will let you do your thing, you know. I think that one of my talents is instinctively seeking these people out and just going for it. Having the nerve to ask and knowing what I wanted to do and who were the masters of it and just going to the source. I always emphasize that to young people. Find a good boss.

“I'm doing what Red does now,” he continues. “I travel to towns and build environmental art pieces and hire local artists just like he did with me. I'm carrying on in his tradition now.”

And before too long, if all the planning comes together as it should, White will mount a big exhibition in his hometown of Chattanooga that he plans to call “Wayne-o-rama.”

“This will be like a history of Chattanooga as seen through my eyes and my sensibility,” he says. “I love history. I grew up with Chattanooga's history. I love the romance of it. I love the characters. Of course, this is also my bid to be a part of the great Chattanooga tourist-trap tradition. In fact, the subtitle is ‘An Homage to Confederama.’”

In all my own family trips up into the mountains of East Tennessee back in the 1960s and ’70s, we visited a goodly number of tourist traps, but I don’t remember Confederama. I ask Wayne to explain.

“Confederama ...,” he says, then pauses, “was really disappointing. It was some tabletop models with little toy soldiers. It was red and blue light bulbs. They would flash on and off where the positions of the troops were in the Battle of Chattanooga and on Lookout Mountain. It was bad.”

That White can look back on such kitsch with love and disdain alike is part of what makes him special. He is a man of extraordinary talent, but great humility; someone who is making it in the art world, which chews up and spits out small-town rubes every day, but without changing who he is.

“I never stopped being a Southerner,” White says. “I couldn't. That's who I was. I wanted that voice in my work somehow. It's something that had to happen. It's all natural getting my Southerness out there, bith the tempered knowledge of not being so proud about it — not being an apologist or even defensive about it, but just being natural about it."

Neil Berkeley, the L.A. filmmaker who directed “Beauty Is Embarrassing,” related to White on that level. He’s not a Southerner exactly, but he’s an Okie. Okies and Southerners get treated pretty much the same in Hollywood.

“You're the hick and all that,” Berkeley says. “I felt that same anxiety, that same aggression. He told me a story one time when I first met him. He probably doesn't remember this, but we were sitting around one time and he was talking about me being from Oklahoma. He said, ‘Don't forget that. Don't forget where you're from.’ He said, ‘When I first came up to New York, this woman said ‘What's your name?’ He said, ‘Wayne White.’”

Berkeley mimics Wayne’s pronunciation of his last name. In southern Appalachia, the word comes out sharply. There is no whooshing, W-H sound in the beginning. The H is dropped, and the “I” is a little flatter than the classical long “I.”

“WITE.” Short and sharp. I had the same problem getting people to understand me when I lived in New York and had occasion to say the word “white” in conversation.

“She kept spelling it wrong and she was laughing at him,” Berkeley says, continuing his story about White, “and he decided right then and there, he said, ‘You know what? I'm not going to change the way I say my name. Not for this woman, not for these people. This is who I am.’

“And that story really stuck with me. Being from Oklahoma, out here ... I think Wayne had a lot to do with me being very proud of that, me being not ashamed and very happy to say where I'm from.”

Wayne says that in his early days in New York, the Southern Thing popped up in his artwork only occasionally. “Every now and then when I would put Southern characters in my comic strips,” be says. But today, through his large environmental-art projects and his word paintings, he gets to be fully and unapologetically who he is. The humor of his word paintings feels like the teenage goofiness of any boy who grew up in the South in the 1970s. Sometimes the paintings bear made-up, hilarious coinages like “Pillbilly.” Sometimes, he goes long, calling on teenage memories to gin up a phrase like this one: “Feathered Roach Clip Hangs From the Ignition Key of a ’73 Chevelle SS and Bounces to the Beat of ‘Immigrant Song’ on the 8-Track Tape Player.”

My personal favorite, though, sums up the way I hope Wayne White feels about his life at this stage, as he mentors young artists and revels in being the designated hillbilly of the art world.

The painting just says, “Fanfuckintastic.”