When the legendary Virginia-born novelist Tom Wolfe died earlier this year, it was 20 years since the release of “A Man in Full,” which skewered Atlanta and even the entire South. Haisten Willis talks to the folks who introduced Wolfe to Atlanta and learns why — despite the skewering — Atlantans loved the book, anyway.

Uncle Bud was a man in full.

He had a back like a Jersey bull.

He didn't like taters. He didn't like pears.

He's got a gal that's got no hairs.

Thus begin the lyrics to an obscure, old Southern folk song, perhaps originating from South Georgia or North Florida, that served as inspiration for the second most famous novel ever written about Atlanta, Georgia.

Perhaps you don’t know the song. Perhaps you don’t even recognize the “Uncle Bud” character. What is a Jersey bull, anyway? And a gal that’s got no hairs? Can one recite this in polite company?

Tom Wolfe certainly did, though he was never one to hold back to keep the peace. One of the leading literary lights of the late 20th century, the Virginia-born Wolfe was by turns bombastic, colorful, controversial, varied, flamboyant, and patriotic.

Photo: Jack Robinson/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

When a man like that flies in to write your city, you take notice. Former mayors personally issue press materials and welcoming statistics on the chosen town. The city’s best and brightest provide guided tours and invitations to $600-a-plate speaking engagements.

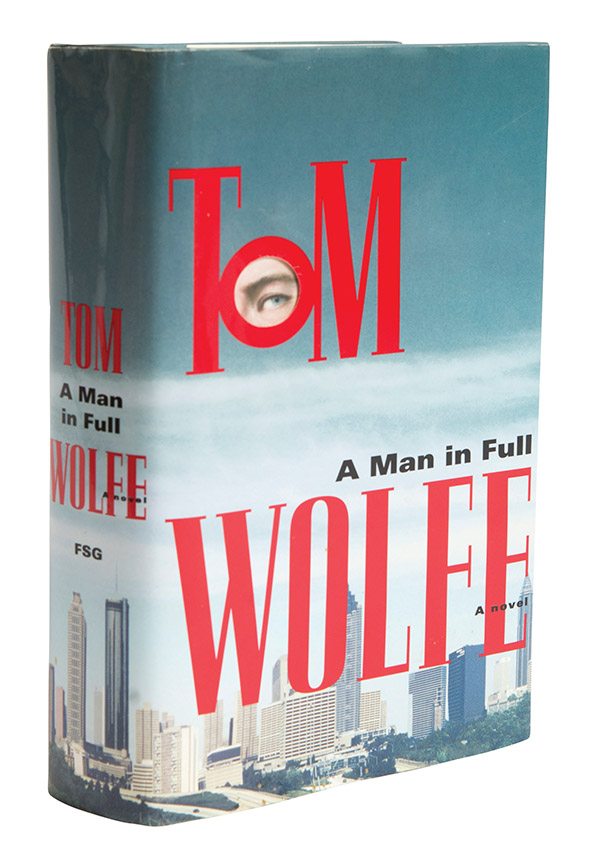

When the man like that, like Tom Wolfe, builds up an 11-year pregnant pause between his first true novel and his second, the one about your city, it becomes a phenomenon worthy of national magazine covers and $7.5 million advances before anyone reads the first word.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Atlanta is the capital of Georgia and the unofficial capital of the entire southeastern United States. It’s a city and region known always for its aggressive boosterism, energy, and economic might, that perhaps can’t flex as much muscle when it comes to cultural impact, history, and tradition. That’s explained in part by its relatively recent 19th century founding. In part, it’s just hard to explain.

Say “Atlanta” to an older person, especially one from outside the state, and if you don’t get an airport story in response, there’s a good chance you’ll receive a comment on “Gone With the Wind,” still the city’s leading literary signifier some 80 years after publication.

Here is Margaret Mitchell describing Atlanta, as told through the infamously acerbic mind of Scarlett O’Hara:

“Scarlett had always liked Atlanta for the very same reasons that made Savannah, Augusta, and Macon condemn it. Like herself, the town was a mixture of the old and new in Georgia, in which the old often came off second best in its conflicts with the self-willed and vigorous new.”

It’s a sentence, written in the Atlanta of the 1930s and describing the Atlanta of the 1860s, that in the 2010s still describes pinpointing the pioneering “Atlanta Way” of boosterism, big business, and economic development, of future first and history fitting in where convenient.

That was Margaret Mitchell’s take on Atlanta. Tom Wolfe wanted his own shot at it.

In November 1998, following a decade of alternating research and recess, he took that shot. “A Man in Full,” Wolfe’s 13th book and just his second novel, debuted that month to overwhelming fanfare. A deafening, blinding roar of hype entered Atlanta and lingered much longer than the research-obsessed Wolfe could ever hope to, with seemingly everyone from local yokels all the way to the national media clamoring to get their hands on his skewering of the South.

And why wouldn’t they?

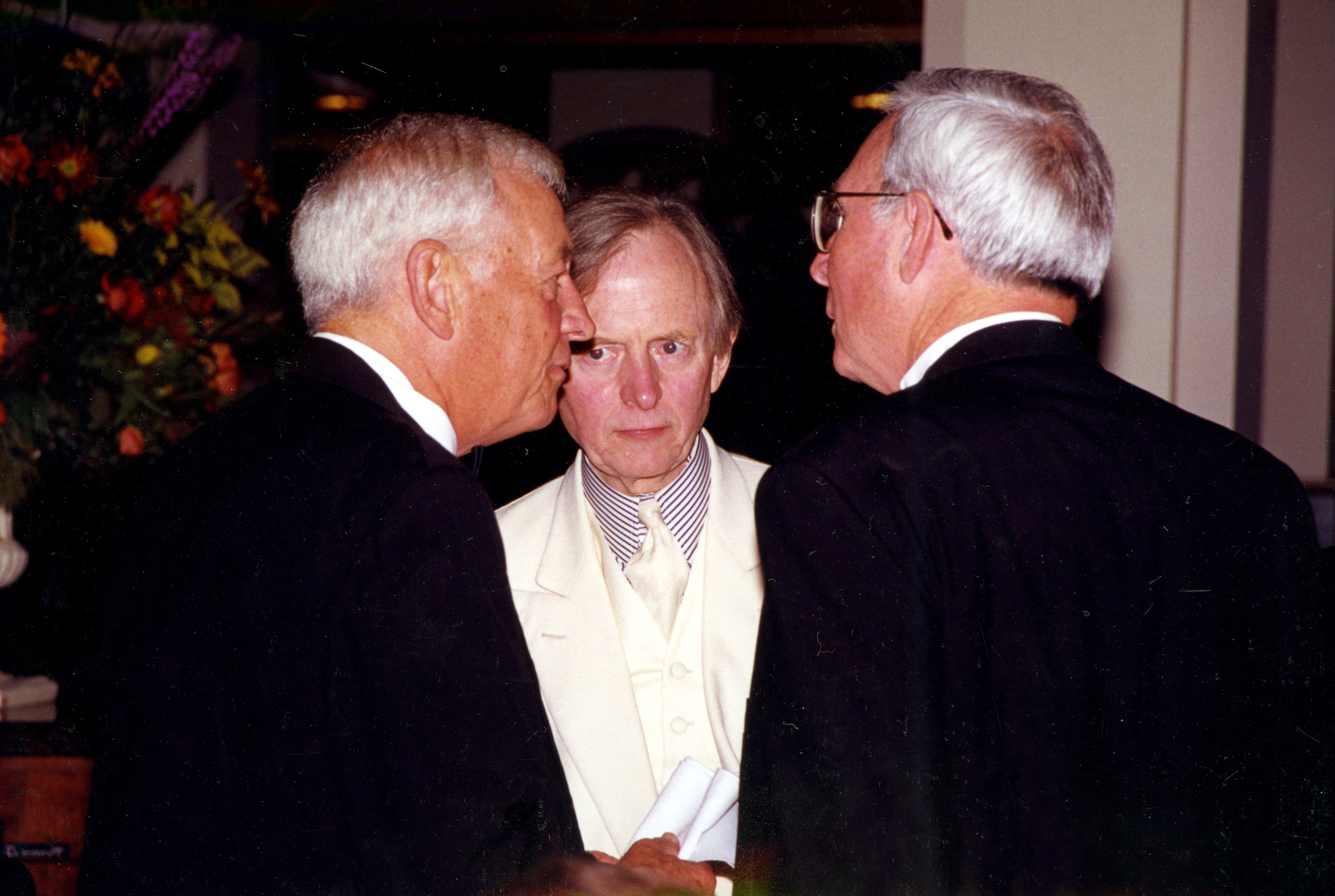

Wolfe, who passed away in May at the age of 88, could be described as many things, perhaps the most apropos a rather tame and boring descriptor: “interesting.”

Photo via Getty Images

The author became nearly as famous for his vanilla white suits as for his Technicolor pen and love for the exclamation point. Though Wolfe resided in New York City from 1962 until his death, it could and should also be said that Tom Wolfe was a Southerner.

Born and raised in Richmond, Virginia, Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr. was the son of agronomist, trade magazine editor, and Virginia Tech professor Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Sr., and garden designer Helen Perkins Hughes Wolfe. He grew up well off, attended private schools, and knew how to throw a baseball, while his mother encouraged artistic pursuits and taught him to love the written word.

Following high school, Wolfe spurned Princeton to continue along the path of Virginia private-school education, choosing Washington and Lee University some 150 west in the town of Lexington. Thus, Wolfe’s life story remained entrenched below the Mason-Dixon Line into his early 20s.

It was in graduate school when Wolfe finally made his move north. A college baseball player, he threw well enough to land a tryout with the New York Giants, and when that didn’t work out, Wolfe trekked another 100 miles up the East Coast to seek a doctorate in American studies at Yale University. Wolfe’s dissertation, though not famous in its own right, lays out a preview of what was to come.

Entitled “The League of American Writers: Communist Organizational Activity Among American Writers, 1929-1942,” Wolfe’s thesis initially shocked the Yale professors who reviewed it, as he chose to ridicule rather than revere the involved writers.

As it would in almost all his later work, status seeking played a significant role in the work, as Wolfe considered status a driver of nearly all human behavior. He earned his Ph.D. in 1957 after rewriting the dissertation from an objective rather than subjective standpoint, but not surprisingly it marked the end of his pursuits in academia.

Instead, Wolfe began his march toward national celebrity status in decidedly modest circumstances: Mailing applications to more than 100 newspapers netted him exactly one job offer, which he accepted at the now-defunct Springfield Union in Springfield, Massachusetts.

That wouldn’t last long, however. Wolfe quickly wrote his way into the Washington Post and then the struggling New York Herald Tribune, of which many contributors became bigger names than the newspaper itself. Joining Wolfe as Tribune alums are John Steinbeck, Gloria Steinem, Jimmy Breslin, and sportswriter Red Smith, among others.

When legendary editor Clay Felker took the Herald Tribune’s Sunday magazine and transformed it into an independent publication titled simply New York, it showcased a certain Southerner who, when asked about story length, was told to continue “until it gets boring.”

With his work for New York and later Esquire, Wolfe became a pioneer of what was called New Journalism, a style bearing little resemblance to anything “new” in journalism in 2018. He’d spend long stretches on a single assignment, penning exceptionally long stories for well-heeled national magazines with the readership and budgets to support it.

New Journalism wasn’t just long, it was loud. Wolfe landed a breakthrough after struggling to complete an assignment for Esquire on California hot rod culture. He finally addressed a letter to his editor on the subject, who ran it word for word after adding a headline: “There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy-Kolored (Thphhhhhh!) Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (Rahghhh!) Around the Bend (Brummmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm). . . . . .”

Tom Wolfe’s legend was born. His first book, with the somewhat abbreviated title “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby,” debuted soon after.

Wolfe wrote nonfiction in the style of a confident novelist, paying careful attention to detail but ignoring conventional journalism techniques. The style landed him millions of fans and, eventually, millions of dollars. Equally flashy was his electric style of dress as Wolfe paraded publicly in peacock-worthy shirts and ties, always beneath that white suit, from the 1960s onward.

It was an exaggerated take on pastel-hued Southern summer fashions, and Wolfe flouted tradition by sporting the white suit far into Yankee territory, ignoring the don’t-wear-white-after-Labor-Day rule. To his critics, the white suit could be described as almost insultingly Southern, a Colonel Sanders caricature designed to elicit a reaction — any reaction — so long as it brought Wolfe attention.

Tom wolfe in New York city | photo by sam falk

In any case, it worked. Even if you haven’t heard of Wolfe, you know his work. The phrases “radical chic,” “the right stuff,” “the ‘me’ decade,” “good ol’ boy” and “catching flak” all were created or made nationally popular by Wolfe. He appeared on national magazine covers, on CNN, on “The Simpsons,” becoming an A-list celebrity in every sense of the word.

Early on, Wolfe was prolific as well. Following the publication of his first book in 1965, he released 10 more by the end of 1982, all of them showcasing his stylized New Journalism, and all of them non-fiction.

But after 1982, that pace slackened considerably. Wolfe completed just six books during the last 35 years of his life, four of them novels.

In 1987, at the age of 57, Wolfe released his first work of fiction, a blockbuster titled “The Bonfire of the Vanities.” Set mostly in upper-crust New York City, it became an international bestseller often described as the quintessential novel of the ’80s, and a poorly received movie starring Tom Hanks and Bruce Willis.

Arriving at the stratospheric peak of his career, Wolfe embarked on what would become an 11-year break before issuing his next opus. That’s not to say he stopped writing. In 1989, Wolfe penned a Harper’s Magazine feature titled “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast,” in which he criticized other novelists of the day for ignoring the crucial research he felt was necessary to create a truly genuine work of fiction.

In true Wolfe style, he offered up himself and “Bonfire” as the model to follow. Feuds with contemporaries including John Updike, John Irving, and Norman Mailer raged on for years.

No doubt research is essential, but 11 years would seem excessive even by Wolfe’s own standards. He claims to have written an entire version of “A Man in Full” set in New York, then scrapped 800 pages only to begin anew with the book in Atlanta.

The change in setting, indeed the inspiration for the entire novel itself, stemmed from visiting a location quite the opposite of his adopted New York City home. Wolfe toured a 2,900-acre South Georgia quail plantation owned by Atlanta mega-developer Mack Taylor and was blown away by what he’d seen.

How had no one written about this?

First, Wolfe was struck by mere existence of a plantation so deep into the 20th century. Second, one of such enormous size and scale, which was maintained year-round at a tremendous expense for use during each year’s 13-week quail hunting season. It was the most conspicuous consumption for consumption’s sake imaginable, a showy, Southern “cuz-I-can” of unfathomable proportions.

No less important, however, was the presence of Taylor’s wife, Mary Rose Taylor. Formerly the wife of television journalist Charlie Rose, Mary ingrained herself in Atlanta’s big business scene after marrying Taylor and, among other things, played a crucial role in the 1990s rescue of the Margaret Mitchell House, the Peachtree Street home where Mitchell wrote “GWTW.”

Anyone with a personal connection to “A Man in Full” notes the role of the former TV news anchor and Buckhead socialite in its creation.

PIctured above: mack & mary rose taylor

“The real reason Wolfe was here was Mary Rose Taylor,” says Sheffield Hale, then partner in an Atlanta law firm and now president and CEO of the Atlanta History Center. “She cannot be given too much credit that this book is about Atlanta. She gave him all the ideas, she supplied him with the research. He was able to interview all of the big developers because of her and her husband.”

Taylor hooked Wolfe up with the Atlanta figures who inspired his next set of characters. She introduced him to the Piedmont Driving Club, whose members look out over Freaknik traffic in an unforgettable early scene. Through Mary Rose Taylor, Wolfe met city planner Leon Eplan, who took the author on a tour of Atlanta recreated by the city’s fictional mayor and a prominent black lawyer in the novel.

When the renovated Margaret Mitchell House reopened in 1997, a project spearheaded by Rose Taylor, Wolfe was on hand in his white suit to address attendees. The Mitchell project and the book that inspired it must have influenced Wolfe as well.

“Gone With the Wind,” which celebrated its 60th birthday in the 1990s, still stood as the best, by some measures the only significant novel set in and about Atlanta. To this day, no less than three metro Atlanta museums serve as monuments to its living history.

This was simply unfathomable to Wolfe.

As he had in “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast,” Wolfe confidently called out his fellow writers for spurning Atlanta.

“There should be 25 or 50 novels about Atlanta by now. What are these novelists doing?” he told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

As before, Wolfe was all too happy to step up to the plate, and after considering the names “Chocolate City” and “Stoic’s Game,” he finally settled on a book title inspired by the obscure Southern folk song.

It’s hard to say exactly how much time Wolfe spent in Atlanta while researching “A Man in Full.” It’s known he took more than a dozen trips to the city, though he never lived there for significant periods of time. This is perhaps apparent in the pages of “A Man in Full.” Atlanta’s landscape and the rolling, green-breasted lawns of the upper-crusty Buckhead neighborhood feature prominently. The stuff of day-to-day life does not. Smoldering summer heat bears little mention, and the only traffic jam in sight plays as a Freaknik side effect.

“There are minor details here and there, not very prominent, but they still reveal that Wolfe was writing the novel from another location,” says Dr. Hugh Ruppersburg, a University of Georgia professor emeritus who has written extensively on Southern literature. “I don’t fault the novel for that. It was very entertaining, very funny, and I thought it captured important things about the city at that time and place.”

“A Man in Full” studied the big picture of Atlanta and the larger-than-life citizens who run the place. There are the wealthy, white Buckhead businessmen who dominate the Piedmont Driving Club and the Metro Atlanta Chamber of Commerce, forever wielding uneasy truces with the black politicians roaming city hall.

Wesley Dobbs Jordan, the novel’s black Atlanta mayor, pontificates at length to Roger “Too” White, a black lawyer self-conscious about his own perceived lacking of black bonafides, on The Atlanta Way.

In a surreptitious nod to Wolfe’s past, he describes the city as an unraveling baseball.

“After you take the white horsehide cover off, you come across a ball of white string, or it’s like string. There’s about a mile of the stuff, once you start unraveling it, all this white string. Finally you get down to the core, which is black, a small hard black rubber ball. Well, that’s Atlanta. The hardcore, if we’re talking politics, are the 280,000 black folks in South Atlanta. They, or their votes, control the city itself. Wrapped all around them, like all that white string, are three million white people in North Atlanta and all those counties, Cobb, DeKalb, Gwinnett, Forsyth, Cherokee, Paulding. ... So how do those white millions deal with that small black core? That’s what leads to the Atlanta Way.”

Jordan and White are educated, enlightened leaders, embodying the hard black center of Atlanta politics. But another character, Georgia Tech football star Fareek “the Cannon” Fanon, similarly embodies its worst qualities. A product of the English Avenue neighborhood, Fannon appears to have no redeeming qualities and nearly no discernible personality. He stands accused of date rape against the daughter of a Buckhead businessman and is despised by all who know him, black and white alike.

The novel embodies the baseball’s white string through Charlie Croker, who appears on the book’s cover and at first blush seems to be the Man in Full himself. Croker, 60, is a Tech football star from another era, a bigoted Southerner with the political tastes of Archie Bunker and a mega-developer who has helped shape the Atlanta skyline.

Croker stages a Ku Klux Klan rally to lower prices on a desired stretch of property. He owns a 29,000-acre quail hunting farm, too — Turpmtine Plantation — staffed almost exclusively by black South Georgians, and treats a group of business visitors to the entertaining spectacle of live-action horse breeding.

Attending a gay artist’s showcase at the High Museum of Art, Croker expounds on the painted image of two muscular men working on a farm. The caption reads “Arrangement in Red Clay. 1923,” but Croker takes the liberty of renaming the piece.

“Two cocksuckers down in a ditch. 1923,” he says in full voice, to the horror of his 28-year-old trophy wife.

But the chief source of conflict in “A Man in Full,” aside from evergreen racial and political tensions, is Croker’s crumbling business empire, which includes holdings stretching across the country anchored by a local real estate enterprise.

Croker has overshot Atlanta’s infamous sprawl, building an edge city way out in Cherokee County, complete with a gleaming office tower named Croker Concourse. A soaring tribute to his ego, Croker Concourse threatens instead to be its namesake’s downfall.

The mega-developer sits in mega-debt, owing to the Concourse. Croker suffers through a “workout” session early in the book that’s classic Tom Wolfe. Readers learn he’s become a “shithead,” banking-industry lingo for clients in arrears on loan repayments, and sweats “saddlebags” through the armpits of his dress shirt.

Simultaneously, Croker’s linebacker build faces the ravages of aging and he begins to feel less and less “full” as the pages wear on. Finally, he’s presented with an escape plan: Utilize his football background and white-businessman bonafides to help smooth the Fannon date rape controversy in exchange for some relief from his business woes.

Said plot surely interested Atlanta’s upper crust upon the November 1998 release of “A Man in Full,” but it wasn’t what drove conversation at the actual Piedmont Driving Club. What they wanted to know was, Who is Charlie Croker?

Several developers shared a claim to Croker’s name. Mack Taylor’s plantation triggered the book itself, and his Perimeter Center edge city possibly fueled Croker Concourse. Tom Cousins certainly helped shape Atlanta’s skyline, as did Ted Turner and John Portman. Kim King starred on Georgia Tech’s football team, and Atlanta Olympics mastermind Billy Payne lined up between the hedges at Georgia. Business giants Charles Loudermilk and Charles Ackerman even shared a given name with the novel’s protagonist.

“People who knew Wolfe was writing the book wanted to make sure their names were spelled right,” said Hale on the book’s buzz. “Atlanta loved the publicity, loved getting the attention of an A-list writer.”

sheffield Hale pictured above. Photo by Shannon Byrne, courtesy of www.iamthemountain.org

The truth, of course, is that all these men likely played roles in Croker’s past and personality. A Man in Full was, in fact, A Man in Composite.

Members of the Piedmont Driving Club likewise enjoyed their turn in the book overlooking Freaknik traffic, no matter how far removed from polite society.

“As soon as both feet touched the pavement of Piedmont Avenue, she started dancing, thrusting her elbows out in front of her and thrashing them about, shaking those lovely little hips, those tube-topped breasts, those shoulders, that heavenly hair.

RAM YO’ BOOTY! RAM YO’ BOOTY!

A rap song was pounding out of the Camaro with such astounding volume, Roger Too White could hear every single vulgar intonation of it even with the Lexus’ windows rolled up.

HOW’M I SPOSE A LOVE HER, CATCH HER MACKIN’ WITH THE BROTHERS?

— sang, or chanted, or recited, or whatever you were supposed to call it, the guttural voice of a rap artist named Doctor Rammer Doc Doc, if it wasn’t utterly ridiculous to call him an artist.

RAM YO’ BOOTY! RAM YO’ BOOTY!”

Hale says he was there when this fictional scene, or something like it, took place, recalling how word got around to Wolfe, who so memorably slotted it into “A Man in Full.”

Appearing, even in fictional form, as a Tom Wolfe character was thrilling. But some men with the biggest and best claims of Wolfe inspiration would rather leave the distinction off their resume.

Chief among them, perhaps, is then-Atlanta Mayor Bill Campbell, a notable absence from the Wolfe fanfare of 1998. Much is made in “A Man in Full” of Mayor Wesley Dobbs Jordan’s light skin, an issue his much darker mayoral challenger spins into campaign fodder by referring to Jordan and his ilk as “beige half brothers.” The fictional mayor goes so far as to hit the tanning bed before winning another term in office.

In reality, the light-skinned Campbell won re-election in 1997 over a darker challenger named Marvin Arrington Sr., with skin tone a rumored political subplot. Campbell released a statement when the novel hit bookshelves touting the “history of racial harmony” in Atlanta.

Twenty years later, and with political career wrecked by a tax-evasion scandal, Campbell stands firmly behind the statement.

“(The skin tone issue) wasn’t accurate then, and it’s not accurate now,” says Campbell, still a Southwest Atlanta resident. “Quite honestly, I thought that was one of the most disturbing, inaccurate and disappointing aspects of the book.”

Campbell says the novel as a whole wasn’t accurate when it comes to Atlanta politics and that he should know.

“I was actually a mayor of Atlanta, so I know the narrative is inaccurate,” he says. “But it’s a fictionalized version and not presented as a nonfiction work. It’s a stylized, fictionalized presentation, and in that regard it’s interesting, but certainly not accurate.”

Wolfe also caught flak from the last white mayor Atlantans elected, Sam Massell, who held the office from 1970 to 1974. When Wolfe came to Atlanta, Massell served (and still does) as president of the influential Buckhead Coalition. Massell sent Wolfe public relations materials on Buckhead upon learning about the novel and initially invited Wolfe to deliver the keynote speech at his group’s exclusive annual luncheon.

When he got a closer look, Massell made a public show of disinviting Wolfe to speak, sparking a feud between the two men.

Now 90, Massell still proudly turns in six-day work weeks, and still says he made the right decision in disinviting Wolfe.

“I saw an advance review, which made me realize that he was butchering Buckhead, not boosting Buckhead,” says Massell. “Up until the time I saw the advance review, I was being fooled.”

Massell, Atlanta’s first Jewish mayor, disagreed not only with Wolfe’s depiction of Atlanta’s leaders, but with their own reception of the work.

“The book fed so many people’s egos. People were insisting that they were Charlie Croker, and they could point to this sentence or that indicator as the reason why,” Massell says. “‘A Man in Full’ told about people doing things that I wouldn’t be proud of. If it’s fiction, fine, but if it’s me, it’s not fine at all. It’s ugly. It’s mean. But they didn’t see it that way.”

In the end, however, Massell figures his conflict with Wolfe played as a minor subplot at best, perhaps driving a few more sales of the book but not figuring much in the wider picture. He still hasn’t read it from cover to cover.

For the larger public and the press, the release of “A Man in Full” was a full-blown phenomenon.

The runaway success of “Bonfire,” combined with the exceptionally long 11-year wait for Wolfe’s next work, created a level of hype equal in proportion to the mythical Croker Concourse depicted in the novel. Indeed, Wolfe created a sensation simply by choosing the unofficial capital of the New South for the setting of his novel.

When the release date finally rolled around, Wolfe appeared on the cover of “Time,” in “Harper’s Weekly,” and about a dozen other national magazines. The New Georgia Encyclopedia says publication of “A Man in Full” became the biggest single event in Atlanta’s cultural life since the world premiere in 1939 of the “Gone With the Wind” movie. The New York Times described Wolfe as a “Literary Sherman in Pastels,” both for his New York (by way of Virginia) origins and his off-white sartorial elegance.

Fully 1.2 million copies rolled off the press in the novel’s first run, and Wolfe earned a nomination for the National Book Award before any of them exited the shelves.

In Atlanta, release hype hit a fever pitch. Wolfe embarked on a three-day publicity tour of the city, including a stop at the Buckhead Borders, where fans waited up to nine hours to secure an acid-penned autograph.

Perhaps the best encapsulation of Wolfe fever was the Journal-Constitution’s “Wolfe Watch” column, which detailed key aspects of Wolfe’s travels, like what he ate for dinner or what type of hat his wife wore on a given date. It was a decidedly tongue-in-cheek gesture and offered a window into Wolfe’s personality.

Far from bothered by all the attention, or what some might call “hounding” from the media, the “Wolfe Watch” column’s most prominent fan may have been Wolfe himself.

Photos courtesy of The Atlanta History Center

Rich Eldredge penned the column and recounted the experience recently on his website, EldredgeATL.com. After reluctantly penning the column for a few weeks, Eldredge finally met Wolfe at a press conference and flung a question his way.

Hearing the name and the newspaper, Wolfe lit up, telling Eldredge the column made him feel like the Beatles landing in America in 1964. Later on, Wolfe mailed Eldredge a copy of the novel, with an inscription reading “your Wolfe Watch made my decade!”

“Tom Wolfe loved, loved, loved the ‘Wolfe Watch,’” says Hale. “Talk about somebody who loved attention. Having his own ‘Wolfe Watch’ was just perfect for him.”

Critics showered “A Man in Full” with attention as well, most of it hailing the book as a comedic and solidly Wolfe-ian take not only on Atlanta but the entire South.

The political “baseball” analogy held sway across the region, as both Birmingham and Charlotte elected their first black mayors within a decade of Atlanta electing Maynard Jackson in November of 1973. The novel's plantation scenes similarly drew connections far outside of Atlanta, providing direct ties both to the South's agricultural and literary history. The obvious example is, again, “Gone With the Wind,” but plantations also feature in the works of Southern authors Erskine Caldwell, Flannery O'Connor, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and William Faulkner, to name only a few.

That’s not to say all the writing establishment was on board. “A Man in Full” found its share of harsh reviews, and found them in high places. The novel served as a flash point for old battles dating at least as far back as 1989’s “Billion-Footed Beast” essay. The trio of Updike, Irving, and Mailer all shot barbs Wolfe’s way, a highbrow feud waged across the pages of The New Yorker and the New York Review of Books.

Mailer titled his review “A Man Half Full.” Updike wrote that Wolfe’s novel "amounts to entertainment, not literature, even literature in a modest aspirant form."

It’s a feud that perhaps hasn’t aged well. Ruppersberg, the University of Georgia English professor, feels the quartet of educated older white men had much, much more in common than its members would like to believe.

“Those were four writers who weren’t fundamentally different,” he said. “There was jealousy going back and forth. Wolfe certainly knew how to provoke those writers, particularly Mailer, but it was a literary disagreement that in hindsight doesn’t look as significant as it might have at the time.”

If Wolfe’s white male contemporaries could be described as harsh, the reception from African American novelist Ishmael Reed was biting. Reed saw the Colonel Sanders archetype not only in Wolfe’s style of dress, but laced throughout “A Man in Full” as well.

“In Wolfe’s novel, which received lavish coverage from The New York Times, one finds the lazy standbys of the Confederate novel, including the black rapist and the incompetent black government, in the city of Atlanta’s black administration,” he wrote.

If the “Wolfe Watch” story is any indication, Wolfe likely didn’t mind the barbs too much. Referring to Updike, Irving, and Mailer as the “three stooges,” he batted down their complaints simply.

“All three have seen the writing on the wall," he said, "and it reads: ‘A Man in Full.’"

With two decades gone since the release of “A Man in Full,” and with Wolfe’s death earlier this year, the only questions left concern the novel’s legacy and how its poster and punchline city fares in 2018 compared to 1998.

Some points are obvious. Plenty of traffic still clogs Piedmont Road, but none of it is related to Freaknik. The giant gathering of students from historically black colleges and universities has passed into history. Other facts remain: Atlanta still boasts a black mayor, Buckhead remains the city’s business capital, and big-shot developers still own overwrought quail plantations in South Georgia.

Other Atlanta assertions hold only in part. The political baseball appears primed to dissolve thanks to the Beltline and a wave of young professionals eager to inhabit “hip” intown neighborhoods. Further afield, creeping suburban poverty threatens to upset post-World War II visions of curving, car-centric neighborhoods filled with nuclear families far removed from urban issues.

“Karma is interesting, the way those suburban communities ended up choking on that growth, sitting in traffic for hours, and how the children of those communities decided they’d much rather be in an urban space,” says Campbell, the 1990s Atlanta mayor. “The millennials are back, and where they have come, the developers are now following.”

Photo: Tina Barney, 2012

Croker’s Cherokee County edge city didn’t pan out in Wolfe’s novel, and would likely fail in the real world, too, thanks to the sudden vibrancy of intown real estate.

Still, other Wolfe observations remain stubbornly resistant to change. English Avenue still counts more blighted buildings than anyone would prefer, in spite of continued efforts of city boosters and even Atlanta Falcons owner Arthur Blank. A 2018 sequel undoubtedly would feature something on the city’s stadium-development obsession.

As Atlanta becomes increasingly international in character and composure, most interviewees agree the Charlie Crokers of the world carry less sway than they once did.

To that end, Atlanta’s Southern bonafides may be even more threatened, for better or worse, in 2018 than 1998. In “A Man in Full,” Croker laments Atlanta’s absence of Southern accents outside his beloved Piedmont Driving Club. No doubt he’d have even more trouble finding a friendly drawl today as the metro population swells past six million, many from points north and west.

When Tom Wolfe passed away on May 14, 2018, the obituaries made much of his white suits, his New Journalism, his work covering the 1960s counterculture movement in “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test,” astronauts in “The Right Stuff,” and bourgeois 1980s New York City in “The Bonfire of the Vanities.”

Much less was made of “A Man in Full,” which debuted when the writer was 68 years old and appears to mark a late-career fade. “A Man in Full” was the second of four novels Wolfe released during his lifetime, and while all were bestsellers, each sold less than the one previous.

No museums serve the legacy of Tom Wolfe’s Atlanta the way they do Margaret Mitchell’s, and it’s doubtful the average Atlantan has read it.

It’s difficult to ascertain why one major novel lives on through time while another, even one with the tremendous momentum befitting a Tom Wolfe work, appears to fade quickly from memory. One can only guess and wonder.

Hale also points out that while “Gone With the Wind,” the supposed cultural predecessor to “A Man in Full,” became a major motion picture equaling or surpassing the fame of its literary inspiration, Wolfe’s novel never got the film treatment in any form.

Ruppersburg offers another theory.

“It’s not a novel that Atlantans want to worship,” he said. “It’s critical of the city in certain ways, and it makes fun of the city and its people. It’s not a celebration of Atlanta, but rather a satirical comedy.”

But despite its detractors, its Pulitzer Prize-winning critics, and its uneasy take on Atlanta, race, and politics, “A Man in Full” stands as a testament to a heady time in the city’s history, with the glow of the Olympics fresh in mind and big-shot boosters pushing the city doggedly into the future.

Photo by Henry Leutwyler/Getty Images

As city leaders pointed out in 1998, Wolfe wasn’t out scouting Birmingham or Orlando for material, and that alone stood testament to the relevance, both economic and cultural, of Atlanta as the capital of the South.

From an anthropological standpoint, “A Man in Full” stands as a 742-page snapshot of a place and a time. Readers many decades on may read of the Atlanta of 1998 as told through Wolfe’s pen and learn for the first time of Freaknik, of the Atlanta Way, of the stubborn plantation motif still not erased from memory in the late 20th century.

Leon Eplan, the city planner who brought to Wolfe’s attention the divided worlds of Buckhead and Bankhead, says Atlanta is only set to push forward more rapidly as time marches on. Now in his early 90s, Eplan still loves speaking of his city’s future.

“By 2040, the projection is for metro Atlanta to have something like 2.5 million more residents,” he said. “We’re talking about 20-, 30- and 40-story buildings going up in midtown in the next few years.”