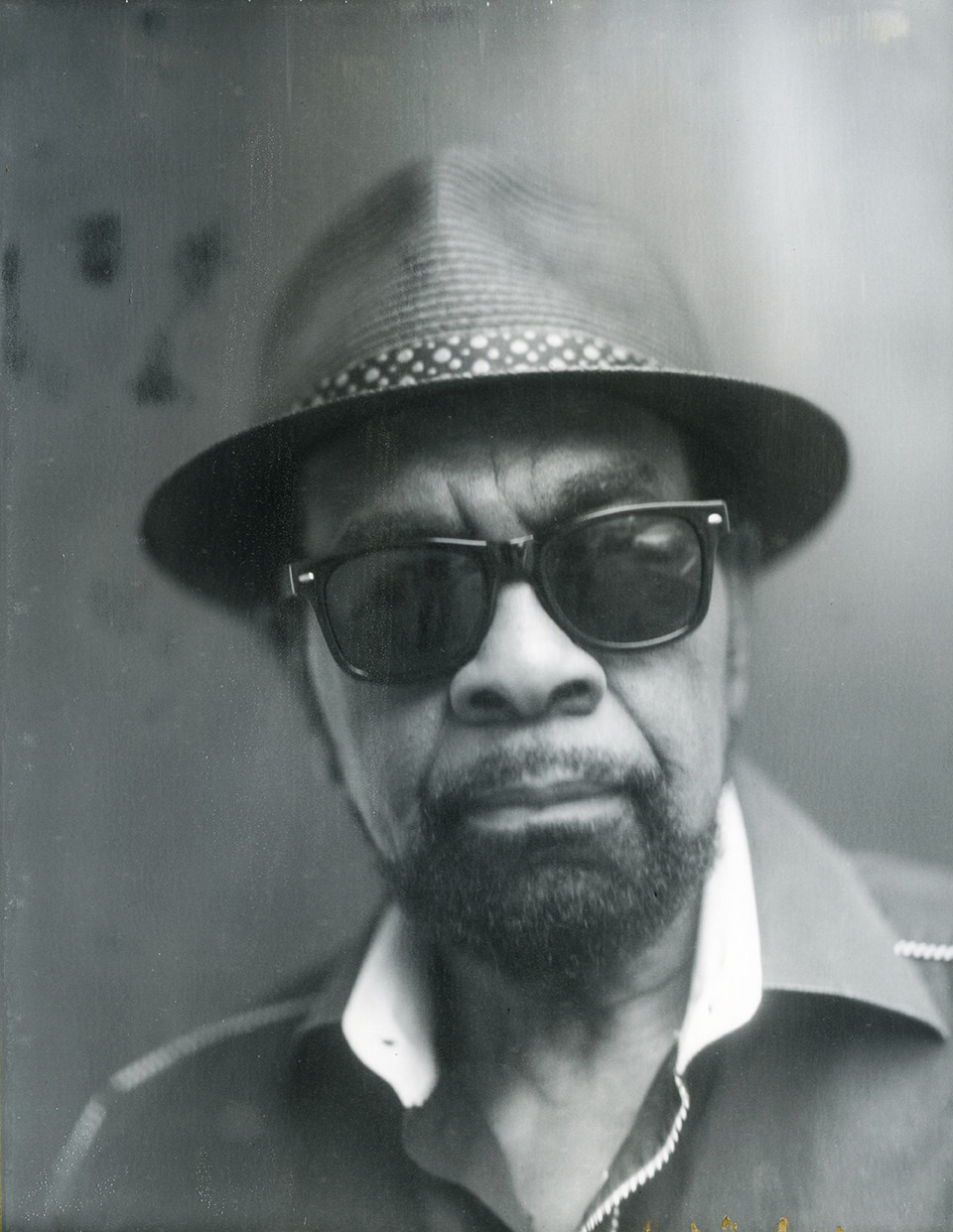

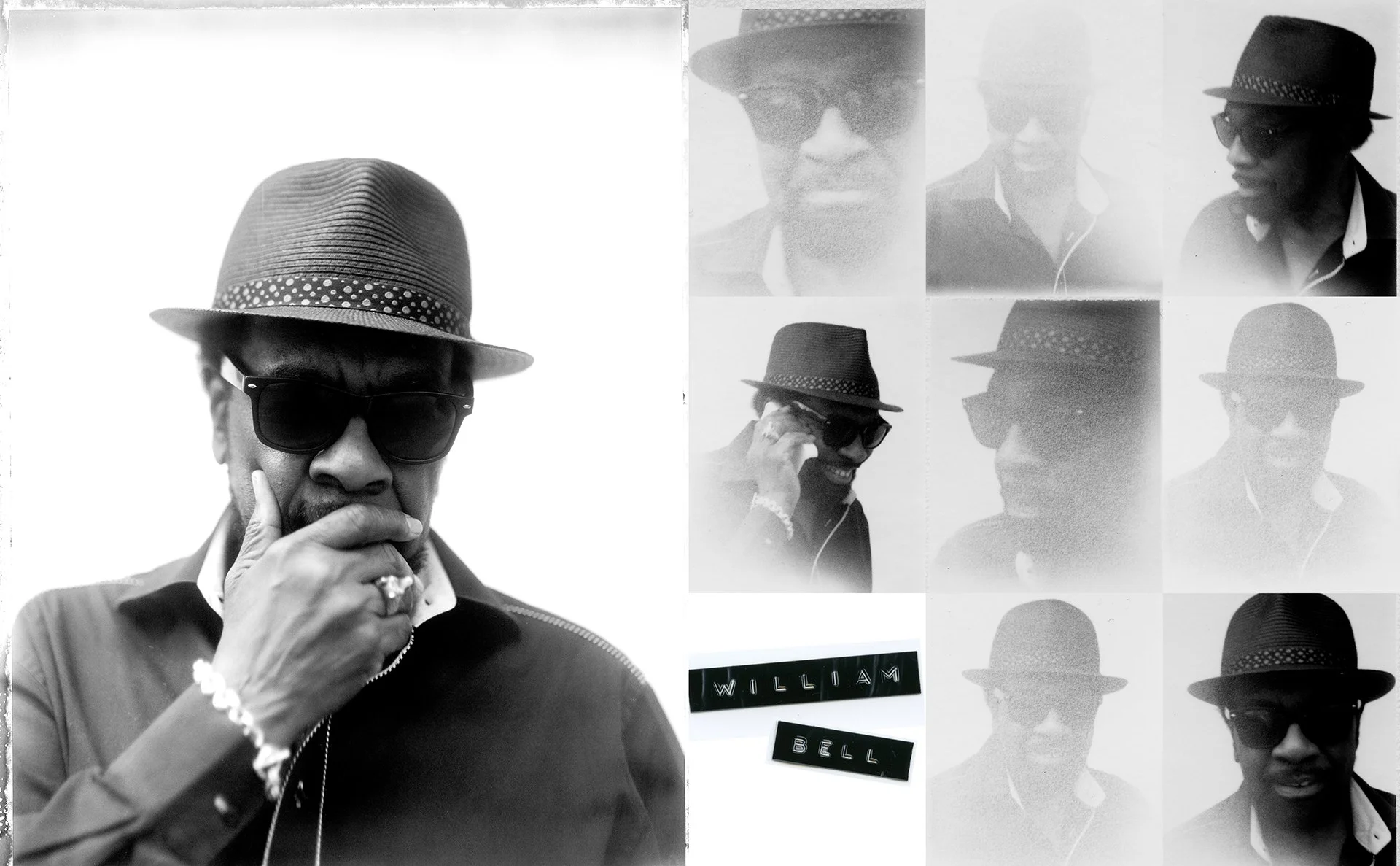

He wrote and sang some of Southern soul music’s most iconic songs. Now, a half century after his career began in Memphis, William Bell, at age 76, is back with what may be the best album of his life.

Story by Wyatt Williams

Photographs by Andrew Thomas Lee

For the third time in his life, William Bell has been talked back into the record industry.

The first time it happened, he was only a kid. As a teenager, he’d written and recorded a single with the Del-Rios, a doo wop group, but it hadn’t made any money. His mother told him, “You’ll be like all of the rest of these blues bums. You’ll die without a penny.” He went to school to be a doctor instead.

The producer Chips Moman talked him back into the recording studio. The first single he wrote and recorded as a solo artist for Stax Records, “You Don’t Miss Your Water,” has since become one of the defining, most durable ballads in soul music, since covered by Otis Redding, the Byrds, Taj Mahal, Peter Tosh, Brian Eno and Sturgill Simpson, among others.

The second time happened in the mid-’70s. By then, Stax Records had gone into bankruptcy. Bell had moved to Atlanta to get in the movie business.

He enrolled in acting classes and scored an appearance in “Together For Days,” an independent film that happened to include the debut of a young Morehouse student, Samuel L. Jackson. The movie wasn’t a hit, even after being re-released under the title “Black Cream.” Today, no one seems to be able to locate a copy. It is considered lost.

Bell became disillusioned with acting sometime after that. Directors wanted him to play hustlers and pimps. He wanted to be Sidney Poitier. So, when Mercury Records asked if he might be interested in cutting a new record, it wasn’t that hard to convince him. Allen Toussaint helped him put together a band. The lead single, “Trying to Love Two,” sold more than a million copies.

The third time happened a few years ago. The reformed Stax Records, now owned by the Concord Music Group, approached him about making another record for the label.

Since the mid-’80s, Bell had been recording and releasing music on Wilbe, his own small label, but his profile had been decidedly low. His studio and offices are unmarked on the back-side of a strip mall near Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport. Many people don’t even know he lives in Atlanta. When the revived Stax came calling, he said he would have to think about it.

“I’m not an impulsive person,” Bell said. “I've seen some horror stories about people who will sign a contract or do something and then they’re sorry afterwards. If they put a rush on me, then I won't do it.”a

Bell thought about it for several years.

Come Friday, “This Is Where I Live,” Bell’s first album for Stax in 40 years, will be released.

This past April, William Bell took a road trip to Macon. His manager, Charles Driebe, picked him up at the Wilbe office and drove the car. Bell sat in the back seat in a pair of Ray-Bans, a wool jacket, a hat. He reflected.

“I was a weird kid. I remember my first record was ‘Unforgettable’ by Nat Cole. Do you remember that one?” Bell asked. The record came out when he was 13. “I would go upstairs and go to bed and put the the covers over me. Had a little old turntable back then that I would sit there and listen to. Didn’t have headphones. My mother would always yell upstairs, ‘Cut that off and go to sleep!’ It was something about the arrangements and strings. It let me daydream.”

Bell wrote and recorded his first song with the Del Rios the following year. They were a quartet of singers like him, kids from Memphis who grew up singing in the church but were lately hearing other sounds. In Memphis, Bell said, “It was music all over the place. Blues, jazz, rock and roll, hillbilly, everything else that you want to name.”

Phineas Newborn Sr., a bandleader whose 14-piece orchestra had been playing Beale Street clubs for decades, was one of the first to notice Bell’s talents. His mother probably would never have let him sing the “devil’s music” if Newborn hadn’t convinced her. The Del Rios didn’t have much luck selling records, though they did get plenty of gigs. Newborn asked Bell to join his band, which was starting to travel the country. Bell came along. He sang for large crowds. They played hundreds of dates.

But Bell was still the kid who liked to get under the covers and daydream about the arrangements and the strings, the world of songs and music. If you ask him about the early days of touring with the Newborn band, he doesn’t talk of parties or money. He is modest when asked about the attention of women. Instead, he might just tell you about one night in New York, lonely and homesick, sitting in a hotel room, when he wrote the lyrics to a song. It took him a few hours.

One of the odd things about the song he wrote that night is that it sounds just as much like the homesick poetry of a teenage boy as it does an ancient spiritual sung by generations of old men. The words are a scarce few rhyming lines:

In the beginning, you really loved me

But I was too blind and I couldn't see

But now you've left me, oh, how I cry

You don't miss your water, till your well runs dry

The following verse is a variation on the first, followed by a bridge and a refrain of the hook. The form resembles a sonnet. In the version that Bell recorded, his first single for Stax, you never question who this boy is. The phrases are confident and uncluttered, his voice honest. You scarcely can hear the teenager anymore. He’s already a wise man. You know exactly what he means about dry wells, even if you’ve never seen one in your life.

Bell left college to tour behind “You Don’t Miss Your Water.” The song was one of the first national hits for Stax. Bell was poised to be the label’s leading man. He lined up a one-week stand at the Apollo followed by a six-month itinerary of gigs. Success looked imminent.

But Bell hadn’t even finished his first week at the Apollo when his mother called. She had a letter from the government, a draft notice for Vietnam. Between gigs, Bell drove over to the enlistment office with the intention of discussing a deferment, of showing off his list of engagements, of trying to work something out. When he arrived and asked to discuss a deferment, the sergeant asked him to raise his right hand. “I didn’t know anything about the military, so my right hand goes up and I repeated after him,” Bell said.

When he asked again to discuss the deferment, the sergeant just replied, “No, you’re in the Army now.” Bell’s uncle had to be called to pick up the car. The next morning, Bell woke up in Fort Polk, Louisiana.

When Bell told this story in the backseat of the sedan, he laughed. He delivered that line about being in the army now as if it were the punchline to a joke. He paused, quiet for a moment. “I’m laughing now. It was not funny then. It was like being put on the chain gang. The Army was like being put in prison.”

Before Bell went in the Army, he was a rising star for Stax, climbing the charts, spreading the Memphis sound. When he came out, things had changed. Otis Redding had a pain in his heart. Sam and Dave were comin’. Rufus Thomas was walking the dog. Stax had evolved into a hit-making machine, stocked with songs being written by in-house writers, and Bell was low on the priority list. The best songs, he said, were passed out like this: “We’re gonna give this to Sam and Dave, this to Rufus, we’ll give this to Otis, and here are a couple of things left over for William.”

It was around this same time that Bell noticed something odd about his contract with Stax. When he recorded a song and sold copies, he was paid artist royalties. But when someone else recorded his song, a clause in the contract diverted most of the publishing royalties to his record label.

If you had listened to a certain kind of conventional wisdom about popular music at the time, then publishing royalties shouldn’t matter that much. Pop songs are supposed to be here today and gone tomorrow. The idea that a hit song in 1961 would be remembered even next year, much less performed or recorded fifty years later, was absurd.

Bell saw something different. He renegotiated his contracts to change the publishing clauses. Instead of waiting for the Stax hit making machine to work for him, he decided to become part of it. With Booker T. Jones, a multi-instrumentalist that played most of the Stax sessions at the time, he began the most productive songwriting period of his life.

Bell says he can’t remember how many songs he wrote with Booker T. Dozens, at least, probably more. Everyone seems to know the one they wrote for Albert King, “Born Under a Bad Sign.” Cream covered that one, as well as just about every blues-rock band since 1968. But the list goes on much longer: “Everybody Loves a Winner,” “I Forgot to Be Your Lover,” “Private Number,” “Everyday Will Be Like a Holiday,” and on and on.

“We’d get into each other’s head,” Bell said. Bell would bring in a couple of verses and a chord structure and Booker T. would play an inversion, maybe pull out a phrase for the title. They’d talk it out. Bell would work overnight. Sometimes they’d finish something in a day. Sometimes they’d knock it around for months. “It’s like prizefighters sparring,” Bell said.

The unusual accomplishment of Bell’s songs from that period is their durability. They possess the strange quality that some people call timelessness. They seem to be as true for Albert King as they do for Gram Parsons, for Billy Idol or Eric Clapton or Linda Ronstadt or Sturgill Simpson, for homesick teenage boys or tired old men, for 1961 or 2016.

When Booker T. moved to Los Angeles, they stopped writing together. Stax eventually went into bankruptcy. Bell left Memphis and tried acting in Atlanta. He had his biggest hit ever for Mercury. Not long after, he started his own record label, Wilbe. After decades, though, Bell says he never worked with another musician like Booker T.

That is, he said, until he was introduced to John Leventhal a couple of years ago. The two are perhaps an odd pair. Leventhal’s a noted multi-instrumentalist and producer of what you might call Slick Americana – Marc Cohn, Shawn Colvin, his wife Rosanne Cash. Before meeting Bell, he’d never produced a soul album before.

But when they started working together, Bell said, it was like meeting another Booker T., somebody who could toss around chord inversions and tweak lines and bring melodies up or down and simply get inside of his head, all of that prizefighter stuff.

When Driebe pulled the sedan into Macon, there was Leventhal’s name on the marquee of The Grand.

PERFORMING TONIGHT: ROSANNE CASH WITH JOHN LEVENTHAL.

“This Is Where I Live” took about a year to record. Leventhal’s studio is in his home in New York. Bell would fly in from Atlanta and stay at the Manhattan Hotel, the same Times Square location he wrote “You Don’t Miss Your Water” 50 years ago, and they’d work long hours, figuring out song after song, polishing every note and phrase.

At the center of it is Bell’s voice, aged and wise but somehow still intact and strong, as expressive as he’s ever been. The result is one of the best records of either of their careers, something that shows two artists doing something each has never quite done before. That doesn’t happen often for a 63-year-old producer and a 76-year-old singer.

Backstage at The Grand in Macon, Leventhal gushed about working with Bell, “When you hear William’s voice and the timbre of his voice and his inflection and the way he sings it, for me it just goes to the heart of what I love about music. He lives in that perfect world of soul, R&B, but you hear the echoes of church, of country music in his writing. It’s that nexus where all these great idioms of music live.”

Bell had come to the show to just watch Leventhal and Cash play, but Leventhal wouldn’t let him get away with just watching. A little before the show started, Leventhal asked, “Hey Big Fish, you want to play a song?”

Bell shrugged his shoulders, sure. They decided to run through it. The auditorium was empty. When Leventhal’s hands touched the piano, the room echoed, reverberated, the way churches and theaters, places of the past, tend to echo. Bell began to sing, his voice quiet, hardly above a hum:

Once I had fame

Oh I was full of pride

There were lots of friends

Always by my side

Well my fame oh it died

Now my friends began to hide

As the chorus came in, Bell’s voice began to warm, to get a little louder. Roseanne Cash walked over from her dressing room to watch.

Everybody loves a winner

But when you lose, you lose alone

They were a bit rocky, off beat, like friends having a first conversation after a long time. But in the next verse, Leventhal’s hands found Bell’s rhythm and Bell’s voice found the room:

Everywhere I turned

There was a hello and smile

I never thought

They'd be gone after a while

Well my bankroll went down

And the smiles turned to frowns

Everybody loves a winner

“Twice this time,” Bell reminded Leventhal.

Everybody loves a winner

But when you lose, you lose alone

In the original recording, this is the moment when a glow of brassy horns comes in, a bridge of jazzy melody.

There were no horns on stage that night. If you love music, you may hope for your entire life to stand so close to the notes that Bell and Leventhal improvised instead. Leventhal’s hands danced around the keys, a little jazz and a little church, while Bell’s voice, already warm, moaned a little melody, their two parts effortlessly in sync. Moments of music like these, when you feel the tune so far inside your gut, explain why they call it soul.

Before the next beat, Bell reminded Leventhal, “There’s a modulation next, half-step.”

“Really, a half-step?” he asked, his hands testing out the keys.

Once I had love

Ah but I couldn't be true

To get back that love

There ain't nothing I wouldn't do

Well I've loved

And I've lost

And now I pay the cost

Everybody loves a winner

“Twice again,” Bell reminded.

“Is it always two? Each time?” Leventhal asked.

But Bell wasn’t listening anymore. He was just singing.

Everybody loves a winner

But when you lose, you lose alone

For a few seconds, no one spoke.

As if to speak for all of us, Cash said, “That was beautiful.”

That night, after the three of them played the song together in front of the crowd, the auditorium erupted into a standing ovation.

The process of making “This Is Where I Live” wasn’t so different than albums that Bell made 50 years ago. Leventhal and him put in long hours, got inside each other’s head, wrote the songs they wanted, made an album they’re proud of. But over those decades, the music business has changed. It used to be, Bell said, “The right two jocks could make a hit.”

A couple guys in New Orleans and Baton Rouge could start playing your song on the radio and the stations in other cities would notice the title on the regional charts. Before long you’d have national momentum. That’s how it worked for “You Don’t Miss Your Water.” But the regionalism of radio no longer exists. The business of making a hit is now more unclear than just slipping a 45 to the right DJ.

The same goes for touring, which once meant getting six or seven soul acts all backed by the same big band into a bus and spending nine months on the road. The chitlin’ circuit is gone, of course; the legendary theaters and halls where that music once thrived are mostly closed.

In recent years, the revived interest in soul has created a different-looking circuit. Bell has lately played one-off events: a showcase of legendary soul men at South by Southwest, a tribute to Memphis soul at the White House, a television appearance on “Later … With Jools Holland,” a recent sold-out show at a little dive in Atlanta to shake the dust off.

The business of appearances like this can be complicated. Bell’s been playing with a tight soul revival ensemble called the Total Package Band for years. When they hit the notes of Bell’s classic tunes, you may think you’ve stepped back into the Stax Studios in Memphis. Unfortunately, flying an 11-piece band across the country for one or two dates does not make much business sense.

So, the innovation in this era of soul music is a surprisingly regional one: Have a band ready wherever you might play. The dates that Bell will play to coincide with the release of “This Is Where I Live” will begin in the Northeast, where Leventhal has handpicked a group of players for the band. Over in Europe, where Bell will play a few dates after that, Bell’s manager Driebe has arranged for a group of musicians based there. A West Coast band is in the works. With the Total Package Band in the Southeast, Bell has it just about covered.

Owing to this unusual arrangement, Bell recently found himself on the ninth floor of a tower in Manhattan, back again not so far from the hotel room where he wrote “You Don’t Miss Your Water” 50-something years ago.

But this was not a hotel room. It was cramped and full with amplifiers and mixing boards and every manner of musical equipment. The room was soundproofed, the door so thick it resembled a bank vault’s. And this was not Phineas Newborn’s band. It was John Leventhal’s, who sat in one corner with his guitar. Aside him were two backup singers, a three-piece horn section, a drummer, a bass player, an organ player. Bell sat facing the band, a stand of sheet music and lyrics between them.

And so, for one more time in his life, Bell rehearsed new songs with a new band. Leventhal led them through the album, beginning with “The Three of Me.” Bell sang the lines:

Last night I had a dream, there were three of me:

The man I was, the man I am, and the man that I want to be.

The curious thing about rehearsing songs after a record has been recorded but before it has been released is that the rehearsal becomes a kind of final revision, one last chance to make changes before people hear it on stage. As they worked through “I Will Take Care of You,” a particularly tricky vocal melody in the chorus was smoothed out. (“It was a studio gimmick that worked, and now it doesn’t work,” Leventhal said.) The horn parts on “The House Always Wins” were fine-tuned to be neither too tight nor too loose, a fine distinction.

No distinction was too subtle for Leventhal’s ear. After each song, he delivered notes to the players: “In the second verse, can you add more Wurly chords, particularly on the four-minor to the five-minor? That moment particularly needs a thing.” “It feels that we are playing the ba-ba-ba ever too staccato. It should be uh-uh-uhh, like a breath.” “We may need horns there.” And so on.

And William kept his eyes on the lyric sheets. The old songs were easy for him, he could sing them with his eyes closed, as he sometimes does, but these new ones weren’t there, yet. A phrase could still elude him, a beat there could still skip by him. He looked down at one point and said, “When you have to remember new lyrics …” He didn’t even have to finish the sentence.

One of the songs they rehearsed that night was written by Jesse Winchester, a tune called “All Your Stories.” It’s a song that has a lot in common with the way Bell writes songs, about an old soldier, somebody who has seen it all before, reflecting on how he got to his present moment. On the album, it comes about midway, a quiet moment with Leventhal finger-picking the notes and Bell carrying the tune. Leventhal explained that he intended to expand it for the stage, to fill it in.

On the first take, the horns played a few tentative notes in the key of D, the backup singers tried filling out a few words. The drummer tapped a simple beat. Leventhal added the occasional flourish of guitar. For the next take, the drummer was directed to let it breathe more, the key-player was asked for “More organ, less Wurly, very light church.”

And on the third take, a new rendition emerged. The band built slowly, each player adding a light touch, building upon one another until those horns hit a full, glowing bed behind the song’s penultimate verse:

Oh now, goodness knows you might have done better

But then, Heaven knows you might have done worse

If you lit up the occasional candle

You're allowed the occasional curse

After that, the band let up and let Bell’s voice breathe out the final few lines:

So relax now and recall

All your old stories forever and ever

All your old stories forever and ever

Later, after the rehearsal, I asked Bell how he was feeling, about the album, about the rehearsal, about the upcoming tour, about all of it.

“It’ll get there,” he said.

That was it. He looked at me and let out a little laugh. He smiled, confident he didn’t need to say anything else. It would get there. He’d seen enough by now to know.