For more than a half century, the folklorist Bill Ferris has allowed Southerners to tell their stories in their voices — so those voices can enable us to understand each other better. Editor-in-chief Chuck Reece sought out Ferris, now retiring after a career that fundamentally changed America’s understanding of the South, to allow him to tell his own personal story.

Story by Chuck Reece

Photographs and recordings courtesy of Bill Ferris, Dust-to-Digital, and the University of North Carolina

They don’t teach mule trading at Yale University, but Bill Ferris had a sneaking suspicion the blue-blooded Ivy Leaguers he ran with in the 1970s might benefit from some practical knowledge, the kind you don’t find in books. That’s how Ray Lum, an 84-year-old Vicksburg, Mississippi, mule trader, wound up spending a late September day in 1975 outside Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library, holding forth to any student or professor who would listen.

Ferris had grown up on a Mississippi Delta farm called Broadacres — “16 miles on a gravel road,” he says, from Vicksburg. He had known Lum “from the time my father would take me to the auction barn” where Lum held his weekly livestock sales. At this stage of his career, Ferris was 33 years old and in his third year as an associate professor in Yale’s American and Afro-American Studies programs. He had long since understood the spell a drawling, self-made raconteur from Mississippi could cast upon the unSouthern. He’d learned it well after years of up-North and overseas education at a Massachusetts boarding school, Chicago’s Northwestern University, Trinity College in Ireland, and finally the University of Pennsylvania.

“When I was in college, I’d bring friends home,” Ferris says. “What were the things to show them [in Vicksburg] that were different? Well, there was the Vicksburg National Military Park, the Waterways Experiment Station, and Ray Lum. I’d take them out there on Monday to the sale and just let them sit there and listen to his stories. They'd never seen anything or heard anything like that. He was greater than life. He was like theater.”

On that day in 1975, Ferris remembers, Lum “sat out on the green all day, never stopped talking, and there was a crowd of faculty and students around him all the time.” Lum even staged a mock auction of one faculty member’s pet — a bulldog just like Yale’s mascot, Handsome Dan. While Lum told stories to the crowd, Ferris got a visit from his friend and fellow faculty member Bart Giamatti, who would later become Yale’s president and then the commissioner of Major League Baseball.

“Bart came out and sat by me and listened to Ray for about an hour,” Ferris says. “He said, ‘I’ve heard Cleanth Brooks lecture on Faulkner numerous times, but I never understood Faulkner until I heard Mr. Lum.”

Such is the magic of Dr. William Reynolds Ferris.

Ray Lum, mule trader: "You live and learn and then you die and forget it all."

Ferris will retire July 1 from the University of North Carolina after a 50-year-plus career of recording Southern voices and sharing them with people who would otherwise not have heard the magic in them. But perhaps the most critical part of his life’s work is how he helped Southerners understand each other better. Long ago, he dedicated his life to letting the South hear itself, thus teaching us what we have in common and showing the connections that happen despite barriers of race and class.

Two characteristics mark all Ferris’ work. The first is his lifelong conviction that Southern culture’s oral traditions — the words, stories, and songs of regular folks — are just as important as its written literature. Second, his approach to what he studies is purely catholic, in the sense of the word that means “comprehensive or very broad in sympathies, understanding, appreciation, or interest: not narrow, isolative, provincial, or partisan.” With his thousands of photographs, field recordings, and films, he has put unheard church choirs, blues singers, and even a Yazoo City, Mississippi, quilter named Pecolia Warner onto the same pedestal as great artists like Alice Walker and Robert Penn Warren.

Why? Because Bill Ferris has always believed our oral traditions — our stories, our songs, our folklore — are the best tools to show Southerners that what they have in common is powerful enough to break the walls of race and class. He has shown us how all Southerners are inextricably connected.

“Studying the South, you have to say we're all part of it and we all are connected,” Ferris says. “It's what Balzac called ‘La Comédie Humaine,’ the human comedy. Faulkner created this Yoknapatawpha County world in which black and white, and old and young, and men and women, they are all in there. And that's how I saw the folklore vision and what I tried to do. You interview everybody, and they're all connected.”

Not only has he unearthed thousands of figurative connections but also hundreds of literal ones that stitch the quilt of Southern culture together.

“You know, Ray Lum the mule trader was connected to Willie Dixon, the blues composer — taught him to ride horses. They knew each other.”

The late mule trader once told Ferris, “You live and learn and then you die and forget it all.” It’s a funny bit of folk wisdom, but Ferris clearly has not lived by it. In his view, what Southerners live and learn should be recorded.

Lest we forget our connections.

This Friday, after 10 years of archiving and digitization, the Georgia-based historical record label Dust to Digital will issue “Voices of Mississippi,” a four-disk set that includes Ferris’ field recordings and films of blues singers, gospel singers, and storytellers. If you want to hear Alice Walker explain that while her stories are set in the South, she is more concerned with “the regions of the mind and heart,” you can hear it here. If you want to hear Ray Lum explain how an honorable trader lives life, it’s here. And if you want to hear Mississippi Fred McDowell sing the blues about a “big fat woman, meat shakes on her bones,” that’s here, too.

The set consists of one disk each of blues, gospel, and storytelling, along with a DVD that includes seven of Ferris’ films from the 1970s. The background material that brings those recordings together comes in a 120-page, hardbound book. The book combines essays from Scott Barretta, who wrote and researched the Mississippi Blues Trail; folklorist and ethnomusicologist David Evans; and Tom Rankin of Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies, with painstaking transcriptions of every song and story the set includes.

“Voices of Mississippi” is the product of a career during which Ferris almost singlehandedly turned “Southern Studies” into a legitimate field of academic inquiry. In 1978, he became the founding director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi. In 1997, he answered the call from President Bill Clinton to head the National Endowment for the Humanities. In 2001, after Clinton left office, Ferris settled in at the University of North Carolina’s Center for the Study of the American South.

Bill Ferris interviews Louisiana novelist and MacArthur Foundation fellow Ernest Gaines in 1980.

Arguably, no person in history was ever better suited than Ferris — by circumstances of birth and geography — to pioneer the field of Southern Studies. He grew up on Broadacres farm, which his grandfather bought in the 1920s. On that farm, five African-American families — all descended from slaves who had worked Broadacres before emancipation — lived and were employed by the Ferris family. But the Ferris family had two things most similarly situated white families lacked: 1) education, and 2) a belief that the black families who were part of their world were equals.

Eugene Ferris, the grandfather who purchased the farm for his family, was the state of Mississippi’s first agronomist. Ferris says his grandfather “milked his way through school” at what was then called the Agricultural and Mechanical College of the State of Mississippi, now Mississippi State University.

“He had no money, and he would milk cows and earn the little money he could get in order to stay in school,” Ferris says. “He was a scholar and a writer.” A persistent back ailment kept Bill Ferris’s father, William Reynolds Ferris Sr., from going to college. Thus, William Sr. became the Ferris who farmed Broadacres. Bill was the first of five children born to him and Shelby Flowers Ferris. Both insisted on the same high educational standards upheld by their generation — not an easy feat on a farm so remote from Vicksburg, the nearest city with schools.

Bill Ferris's younger brother, the late Grey Ferris, with his father, William Reynolds Ferris Sr., in the fields on Broadacres farm.

"There were no schools, so she had to figure out how to educate her five children,” Ferris says. “She had read about Montessori, and she wrote and got the books and read them. And then she taught her children using the Montessori method. And they obviously succeeded educationally, because two sons became doctors. They all graduated from college, and one of her daughters, Frances Ferris, went to Mississippi University for Women and then to Smith College [in Northampton, Massachusetts]. My uncle Eugene was a professor at the University of Cincinnati when we were growing up, and they would come to the farm with their children and often with their colleagues … highly educated people and we were going to a little country school near the farm where each teacher taught two grades and no one else had family who had ever been to college. Most of them never graduated from high school. So we were kind of between those worlds.”

Joe Cooper and James "Son Ford" Thomas at the Main Street Cafe in Leland, Mississippi, in 1976. Thomas, a bluesman, storyteller, and sculptor, is documented extensively on "Voices of Mississippi."

Growing up the eldest of five siblings on Broadacres farm, Ferris lived a childhood “sort of like Huck Finn,” he tells me one bright spring morning as we sit over coffee in the home he shares with his wife, the Southern foodways scholar Marcie Cohen Ferris.

"I mean, we could come and go as we pleased,” he says. “When I was 5 or 6, I had a horse named Dave, and I could talk to him.” Ferris demonstrates, shaking his head and whinnying. "I felt like I could speak to him, and I would catch him out in the field and get on his back, bareback, and ride into the barn and put a bridle on him. I didn't use a saddle. I'd ride around the farm. I had the freedom to go and do whatever I wanted as a child.”

The world of Broadacres was one in which the Ferris children were surrounded by family and constant activity.

“It was in many ways a complete world if you were a child,” he says. “My grandparents — my father's parents — lived in a log cabin that daddy had built for them, and so there was all kinds of activity around our family and the other families on the farm. There was always adventure. An abandoned fawn my father brought up, we adopted that fawn and called it Bambi. I mean, that deer was like a dog. It would come in our house and walk around. My mother would have her bridge club, and Bambi would walk through. Then, eventually she grew up, and she would bring her fawn back to the house. We'd feed her a banana. An owl got injured — Hoot, Daddy called it, and he kept it on a perch out front until it recovered.”

When Ferris refers to the “other families on the farm,” he means the five African-American families who lived and worked there. He remembers summers on Broadacres when he and his late brother Grey joined this integrated team of families who worked the farm.

“It was a team, and in the summers my brother and I were part of it,” Ferris says. “We were there every day, especially during the hay season. We would often bring friends to add to the crew for baling hay and for loading it onto trucks and carrying it to the barn. We worked with the five men and their families who lived on the farm.”

The hay-baling team on Broadacres.

In his essay included with “Voices of Mississippi,” Scott Barretta quotes Ferris: “My father always said, ‘You can learn a lesson from every person you meet in life,’ The black families on the farm were a really important part of our family because they took care of us if my parents were away, and we spent a lot of time with them growing up. … There was a freedom associated with their world, and music was part of it. A lady, Virgil Simpson, would take care of us when my parents went away. She would turn up the music on the radio and let us stay up past midnight, dancing. My parents would come home and say, ‘You children, get in bed!’”

The young Ferris was entranced by the stories he heard from the black families and by their unaccompanied voices rising in gospel song from Rose Hill Church, where they worshiped. Before long, he began to document their lives with a Brownie camera. In fact, the oldest of Ferris’ photographs included in “Voices of Mississippi” was shot when he was only 12 years old, in 1954, from where he sat on a hilltop overlooking Hamer Bayou, where the congregation of Rose Hill was holding a baptismal service.

Soon after, he acquired a tape recorder and began recording their songs and stories.

“I never appreciated fully at the time what an amazing life my parents made possible for us,” he says.

The congregation of Rose Hill Church in 1967.

Consider, for a moment, just how uncommon the young Bill Ferris’ life was, particularly in the Mississippi of the late 1940s and early ’50s. He was raised by highly educated people in a house filled with smart conversation. He worked and lived with black families without prejudice. And until he finished the sixth grade and began attending high school in Vicksburg, the limits of Broadacres farm were, essentially, the borders of his whole world. Jim Crow laws didn’t apply on Broadacres; thus they were not part of the young Ferris’s experience.

“I mean, you just grow up in a community and you believe that's the way the world is, right?” Ferris says. “You assume everyone is that way, but they weren’t.”

Carr Central Junior High School in Vicksburg opened his eyes to the evil prejudices that permeated the South of the 1950s. But the same year Ferris entered high school, his aunt, Frances Ferris Hall, who lived in Chicago at the time, enrolled her son and Bill’s cousin, Bronson Hall, at the Brooks School, a preparatory academy in North Andover, Massachusetts. In 1956, William and Shelby Ferris decided young Bill should finish his high-school education at Brooks.

Bill wasn’t keen on the idea.

“I never wanted to leave the farm,” he says. “Whatever it took to stay there was what I wanted. And the idea of separating from your family and places you had grown up in was threatening. But my parents wanted that, and I, you know, did whatever they said.”

At Brooks, Ferris first experienced a different prejudice — the sort that emerges anytime a Southern accent is dropped into foreign territory.

“It was like another country,” he says. “They couldn't understand my English because I had a strong Southern accent. There was a lot of hazing, and being from the South, I got my share of that. But it was a great school, with great teachers and a headmaster whom I loved named Frank Ashburn. It really changed my life in very important ways and kind of opened me up to a world that I didn't know existed. Robert Penn Warren once told me that a fish never thinks about water until he's out of it. And I never thought about being Southern until I went to Brooks. I just figured everything was like the world I grew up in, but then you realize it's not. And so I began to write about the people on the farm. I wrote a short story called ‘Shorty Boy’ about Robert Appleton, and I wrote other stories about hunting and life in that world, which people at Brooks thought were amazing. They had never heard of anything like that.”

Robert "Shorty Boy" Appleton in 1963.

After his graduation from Brooks, Ferris came back to the South and enrolled in North Carolina’s Davidson College. The year was 1960, and in the three years Ferris had been away, the Civil Rights Movement had reached a fevered pitch. College campuses were becoming cauldrons of social action, and Ferris quickly became one of about 25 Davidson students who was actively involved.

The students organized a meeting with COFO, the Council of Federated Organizations, an umbrella group that organized the activities of civil-rights group working in Mississippi.

“It was during Freedom Summer, and my father said, 'I want to go with you,’” Ferris remembers. “He was genuinely interested. We met at the black Catholic church with Bob Moses [a key figure in the movement] and sat around a table speaking. At the end of the evening, Moses looked across the table at my father, and he said, ‘This is the first time I've ever had a civil conversation with a white Mississippian.’

“My father was a farmer, you know, but he was more than a farmer.”

For Ferris, getting involved in the movement buttressed his belief that if the stories of regular Southerners, of all colors and cultures, were better known, attitudes would change. He regularly came back to Mississippi to record and photograph.

“I just followed my heart basically,” he says. “I grew up on this farm. I loved my family and the people there, and I kept looking for a way to keep that anchor in my life as an academic. The study of the South ... I mean, I was doing it, but in my head, I was just listening to music and recording and filming.” And his parents were skeptical. “They thought, ‘How would you get a job on the basis of interviewing blues singers and quilt makers?’”

Ferris didn’t figure out how to get that job until 1965. He had finished his master’s degree at Northwestern and had landed a Rotary International Fellowship to study at Ireland’s Trinity College for a year. In Dublin, over breakfast with an English professor from Ohio State, Francis Utley, who was studying in Ireland, Ferris complained about the constraints of academia.

“I told him they were so narrow, they wouldn't allow you to study the blues and folk tales as literature,” Ferris says. “And he said, ‘Well, you should be in folklore.’ I said, ‘What's that?’ And that opened my eyes. Thanks to him, I ended up at University of Pennsylvania, and that gave me the freedom to do what I really wanted to do.” The next year, when he arrived at Penn to begin his doctoral studies, he discovered his advisor would be Dr. Kenneth Goldstein, who was among the pioneers of the study of folklore.

“When I first went into the folklore program at Penn, I went in to see my advisor, Kenneth Goldstein,” Ferris says. “I had a box of tapes and photographs, and I put those on his desk, and I said, ‘Dr. Goldstein, this is what I've been doing. Can I do that here?’

“And he said, ‘That, my boy, will be your dissertation. Keep doing it.’”

Quilter and storyteller Pecolia Warner, Yazoo City, Mississippi.

Ferris earned his Ivy League Ph.D. in Folklore in 1969. For most of the next decade, he continued collecting Southern stories, and he taught — first at Mississippi’s historically black Jackson State University, where he first met writer Alice Walker, and then at Yale. In Jackson, Ferris lived on Guynes Street, two doors down from where Medgar Evers was assassinated.

In 1972, he and film producer Judy Peisner founded the independent Center for Southern Folklore in Memphis, which gave Ferris an outlet for his continuing work in the field. The CSF remains active under Peisner's leadership today, focusing its work primarily on the history of Memphis, but Ferris was involved only until 1978, when he got the chance to realize his dreams on a bigger scale. He was invited to become the founding director of the University of Mississippi’s Center for the Study of Southern Culture.

“When I was in college and later, I was studying the South, but there was no field called Southern Studies,” he says. “There was no discipline that you could take courses in. And when I was asked to come back and start that center at the University of Mississippi, I based a lot of what we did there on my experience in Afro-American Studies and American Studies at Yale, where I'd been asked to join three other faculty in 1972 and to create an introductory course to Afro-American Studies. So in Mississippi, seven or eight years later, we did a version of that for Southern Studies. And it worked.”

James "Son Ford" Thomas's chance encounter with poet Allen Ginsberg in Houston, Texas, in 1980; Alice Walker in 1976.

Boy, did it. It wasn’t long until word began spreading about the symposiums the Center was staging. The black poet and jazz critic Amiri Baraka came to Oxford to talk about jazz’s roots and fell into a discussion with Dena Epstein, one of the earliest researchers of American slave music and arguably the first to drop the news on America that the banjo was not a white man's instrument — it was African. The Center even invited the late folk artist, Rev. Howard Finster, to deliver a sermon on the subject of Elvis Presley at a symposium dedicated to the rock and roll icon.

Such moments set off sparks in curious students like John T. Edge, who would go on to found the Southern Foodways Alliance as part of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture.

“I was inspired by the public programming of the center,” Edge says. He remembers the Elvis conference vividly.

“It was greeted with derision by some,” he says. “‘What? You’re gonna study Elvis?’ But to me, that was really emboldening. We were going to think about music as a cultural output. We were going to think about this iconic figure. But to many, that was anathema to the academy.”

But if the academy’s job is to spark a thirst for knowledge among its students, you can’t argue with the Elvis conference’s results.

“I was like, I’m in, man,” Edge remembers. “This is powerful stuff.”

Ferris was already at work training others to capture the oral histories, songs, and stories of the South, and the Center’s conferences allowed those stories to mix in ways never before seen.

Scott Dunbar, whose "Jaybird" is one of the most compelling recordings on "Voices of Mississippi"; Shelby "Poppa Jazz" Brown hosts a house party, 1968.

“For me, the recording of these voices was a political act because so many of them were black and others were white, but they were all left out of the record, whether it was a blues singer who was black or a mule trader who was white. Both of them were voices that, without the act of recording and filming, would be forgotten. By recording them and doing what I did, then you elevated them to kind of timeless presence in the memory of the South and of the healing experience.

“We wanted to build a research center that would focus on culture and civil rights within a world [the Ole Miss campus] that had denied blacks the right to study until James Meredith.” Meredith was the first African-American student admitted to Ole Miss, in 1962, and his admission happened only under threat of federal intervention by the Kennedy Administration.

The ultimate purpose, Ferris says, was to openly acknowledge the South’s “violent, tragic history” and “mold out of that a kind of forgiveness and a better future.”

Otha Turner, the late king of the Mississippi Hill Country blues fife, with his signature instrument, handmade from bamboo (with some help from a pocket knife).

The two words one hears most often in a conversation with Bill Ferris are “worlds” and “voices.” In his mind, we all come from our own worlds and thus have our own voices, and he believes all of those voices are worth hearing.

“Everybody has stories, and those stories break down, make everything human, reduce everything to a common level,” Ferris says. “We're all born and grow up and have our lives and then we die and that's it. As Ray Lum said, you live and learn and then you die and forget it all. That's a kind of wisdom that we all need to think about. What you learned and you know, what have you left, is any of it worth remembering? Or does any of it make you feel good about yourself? Each person has a kind of higher standard they look to. Martin Luther King was the master of raising the bar and challenging people to be better than they were — to try to address moral issues, not just make a lot of money or get a bigger house, but also help people who need help in ways that you can.

“That's why I went into education,” he continues. “I had one great teacher who changed my life. And I thought, well, if, you know if I could do that for some of my students, that would be a life well lived. You know, you help people go on and have a better life. And in so doing, you make this world a better place. It's not something you can measure the way you measure your birthdays.”

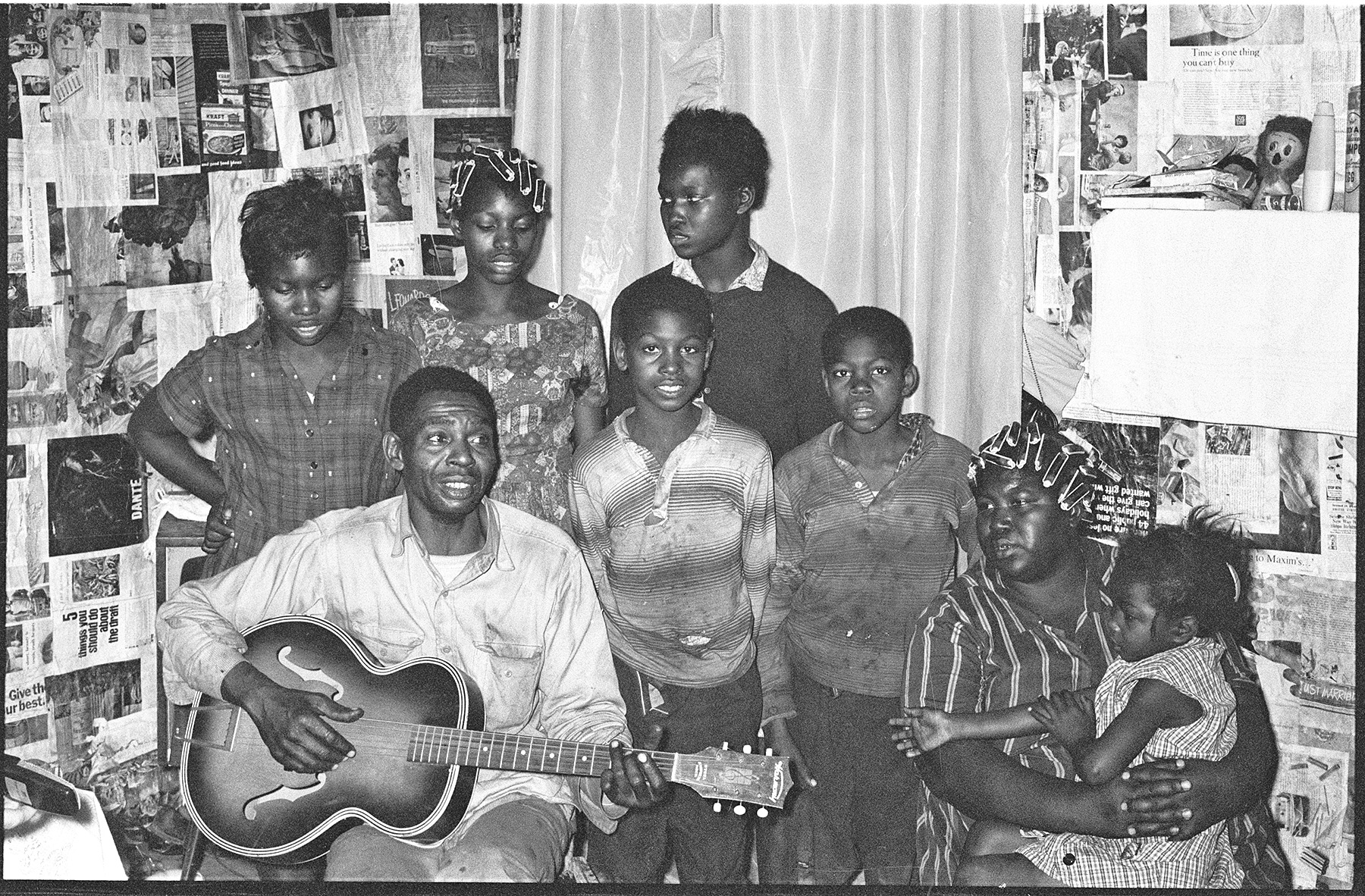

Tom Johnson, who tells the story of his "praying pigs" on "Voices of Mississippi"; Lovey Williams and family, 1965

You can take a stab, however, at measuring Ferris’s influence by looking at the roles his former students play today in efforts to make this world a better place. There is Edge, of course, who two decades of work at the SFA have changed fundamental assumptions about the South and its food. There is Jon Peede, now the chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities. There is Ron Nurnberg, the executive director of Teach for America. There are musicians who entertain and challenge us, like Jo Jo Herrmann of Widespread Panic and M.C. Taylor of Hiss Golden Messenger. And four years ago, another of Ferris’s former students, Katie Blount, took over the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, which oversaw the completion and recent opening of the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum.

“I couldn't have imagined that when I was growing up,” Ferris says. “And then you walk through it, it's packed with black families who finally have a place they can come and see their stories on the walls and hear the music and the voices. For so long, you would go in those museums, and it would be an all-white thing. There was nobody there that looked like you if you were black. But now, here are all those people, many of whom gave their lives to create this monumental museum. It’s radical.”

I expect what Ferris sees when he visits that museum is a reflection of what he has hoped for since his days riding bareback on Broadacres farm — a monument where every Southern voice stands in a place of equal honor. A place where we remain open, always, to the voices of people who are not like us.

“The academic process is not that complicated if you really look at what matters,” Ferris says. “It's about trying to humanize life and making you see other people. My father always said, ‘You can always learn a lesson from each person you meet in life,’ and I think of this African proverb that I love to tell my students when I start a class: ‘When an old woman or man dies, a library burns to the ground.’ You begin to see humanity rather than faceless worlds. And for me as a folklorist, it’s the human voice that allows you to enter that intimacy and break down the barriers, the silos, or, as Rev. C.L. Franklin would say, to let your hair down. I tell my students in my Southern music class, you won't remember my lectures. What you'll remember are these sounds, like the ballads and Sacred Harp of white people or the work chants of black people. The music you hear, some of it's going to really get inside you, and you will carry that with you.

“And it's going to open you up.”