Seeing Eudora Welty Seeing

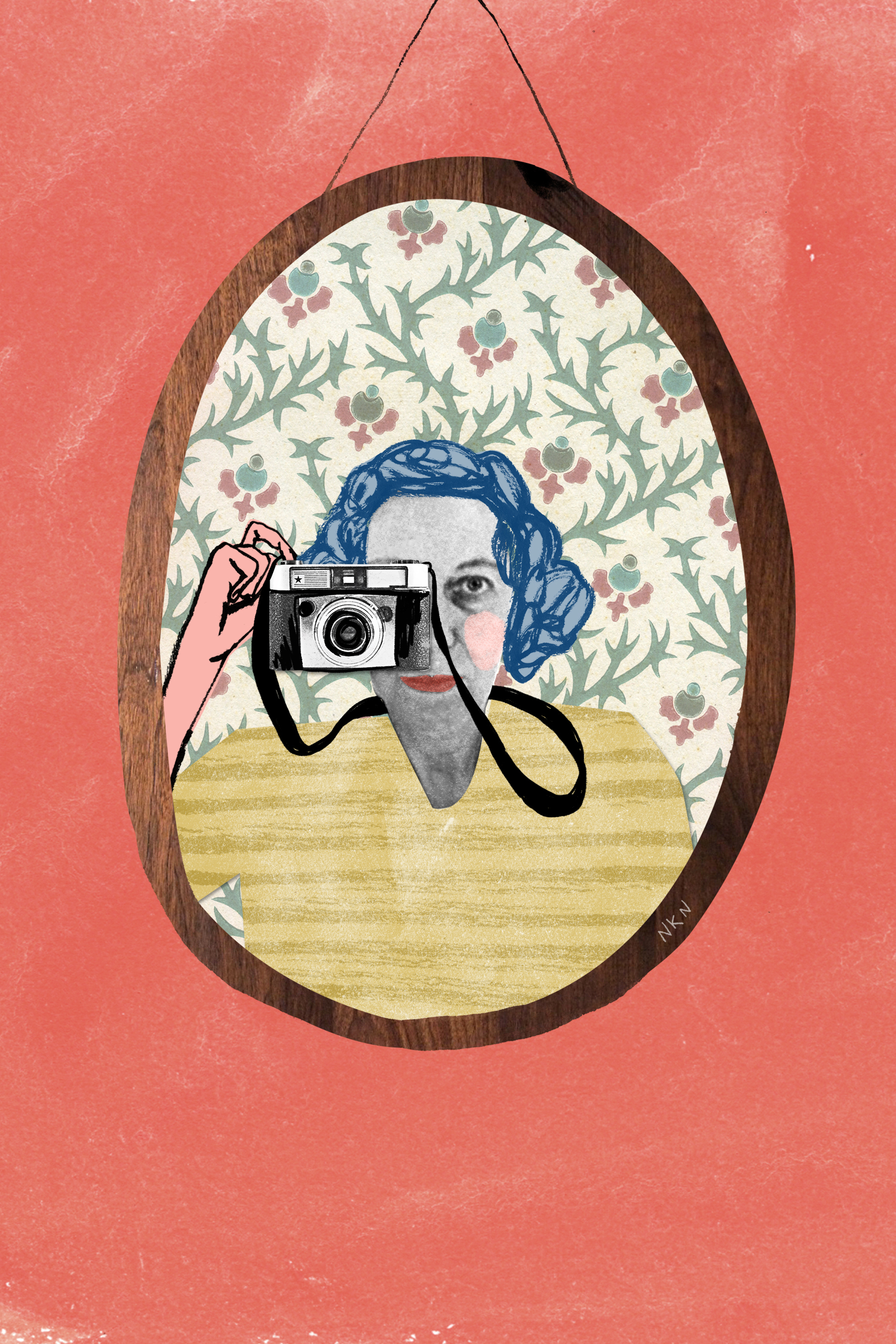

Story by Pearl McHaney | Illustration by Natalie K. Nelson

Eudora Welty has always had an eye for eyes.

Her first novel, "The Robber Bridegroom" (1942), which she alternately called a “Fairy Tale of the Natchez Trace,” is replete with blinking, sleeping, batting, shining, rolling eyes — eyes that are yellow, somnolent, large, worldly, sharp, or tearful. Maybe this is to be expected, so I checked the next novel, "Delta Wedding" (1946). There I found loving, seeking, swimming, opening, shutting, flickering, cutting, forgetful, slumberous, mischievous, soft, weak, wide, long, grey, hazel, dark-blue, red, or lighted eyes. Again, not necessarily surprising. But in "Delta Wedding," I came across this curious line: “The grown people, like the children, looked with kindling eyes at all turmoil, expecting delight for themselves and for you. They were shocked only at disappointment.” Kindling eyes? My own eyes were arrested at this strange and confusing adjective, and so I searched my American Heritage dictionary where my faith and trust in Welty’s deliberate choices were rewarded. The fourth definition is “to be stirred up; rise” out of the Old Norse to Middle English, “to give birth to, to cause.” Of course, I was digressing from my assignment here, but while I was there in the dictionary, I noticed that a kindle is also a litter of kittens and the verb “kindle” in this sense is to give birth, especially to rabbits. Aha! The grown-ups and the brood of children in Delta Wedding “look with kindling eyes at all the turmoil, expecting delight” from the generations of siblings and cousins all falling together for the week of the harvest-time wedding of the prize daughter to the red-haired overseer, just as one might look on a crawling, mewing, jumble of kittens.

This digression emanates from my seeing artist Natalie Nelson seeing Welty peering into her living room mirror, using her camera as a mechanical eye to take a selfie so that observers might see, oddly enough, exactly what Welty sees. But we should be aware that in looking at Nelson’s painting, we are being seen by Welty as well. This is Welty’s genius. With her generous, observant, discerning eye, Welty sees the complexity of human relationships and shows this turmoil to readers of her writing and viewers of her photographs. She does so, she explains, by rooting her characters in place, and ...

“It may be that place can focus the gigantic, voracious eye of genius and bring its gaze to point. Focus then means awareness, discernment, order, clarity, insight—they are the attributes of love. The act of focusing itself has beauty and meaning; it is the act that, continued in, turns into meditation, into poetry. Indeed, as soon as the least of us stands still, that is the moment something extraordinary is seen to be going on in the world”

— “Place in Fiction,” 1955

Indeed, indeed. Something extraordinary like a bridegroom who is also a robber, or a wedding of the daughter of the plantation patriarch to his hired man, or Natalie Nelson drilling in on Welty taking a self-portrait, or us gathering to read, laugh, see anew one of the 20th century’s finest writers.

Welty recognized the powerful metaphor of the eye when she titled her 1965 essay about Katherine Anne Porter, “The Eye of the Story.” The appropriateness of the metaphor might have rested had Welty not titled her collection of selected reviews and essays in 1971, "The Eye of the Story." Now we also have "Welty: The Eye of the Storyteller" (a collection of essays edited by Dawn Trouard, 1989), "A Writer’s Eye: Collected Book Reviews" by Welty (1993), and my own 2014 book "A Tyrannous Eye: Eudora Welty’s Nonfiction and Photographs."

Importantly, Nelson portrays Welty as a photographer, alerting viewers of this significant talent of the award-wining writer. Welty, we now understand, pursued photography as a legitimate career in equal earnest with the writing of fiction in the early 1930s. She was not deterred by not getting a job photographing scenes of government projects along with the now-famous WPA photographers Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, and Marion Post Wolcott. She was not deterred when New York publishers rejected her photographs of Southern African-Americans and her collections of photographs and stories. What she did do was continue writing and taking photographs without an agenda and without an audience. When her first story, “Death of a Traveling Salesman,” was published in 1936 and then more and more stories found print and awards, Welty realized that writing was her vocation and photography an avocation. Nonetheless, she exhibited her photographs in 1934 in Jackson, Mississippi; in 1935 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina; and in 1936 and 1937 in New York galleries. Her photographs were published in "Eyes on the World" (Simon and Schuster, 1935), Life magazine (1937 and 1938), "Mississippi: A Guide to the Magnolia State" (WPA, 1938), and Vogue (1944). Finally in 1971, Welty published 100 of her 1930s photographs in a collection she titled "One Time, One Place: Mississippi in the Depression: A Snap-shot Album" (reprinted in 1996 by University Press of Mississippi). She showed slides of 32 of the photographs in 1973 for a program at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Since then there have been many exhibitions, and photographs have been printed in limited quantities for collecting, and published in academic studies and coffee-table-sized collections. Welty’s photographs show people at work, at rest, in conversation, and in laughter; they show landscapes, parades, and the built environments of homes and communities; some are anecdotal and others are formal — studies of shadow, line, and perspective. Often, as illustrated in Nelson’s painting, Welty’s photographs are humorous. Imagine Welty in front of her mirror, framing herself against the flowered wallpaper, her hair and lipstick just right, balancing her clear, wide, blue, naked eye with the big, black aperture of the camera controlled by her long-fingered hand, ready to click before she has time to say “smile.” Such a photograph does not exist, so we are grateful for the imagined image caught by Natalie Nelson in her painting.

The oval wood frame of Welty’s selfie is as important as the camera eye. In her essay “Place in Fiction,” which is about far, far more than place or the South (as is most often assumed), Welty writes, “We have seen that the writer [read 'artist' of any medium] must accurately choose, combine, superimpose upon, blot out, shake up, alter the outside world for one absolute purpose, the good of his story [i.e. art]. To do this, he is always seeing double, two pictures at once in his frame, his and the world’s, a fact that he constantly comprehends, and he works best in a state of constant and subtle and unfooled reference between the two.” Nelson captures a moment and frames it to hold it steady. She gives us Eudora Welty “two pictures at once,” bringing the writer and the photographer into the 21st century for us to comprehend anew as we read her work or see her photographs and find meaning in what her genius eye is able to show us.

Welty, Eudora. Delta Wedding. Complete Novels. New York: Library of America, 1998. 89–336. “Place in Fiction.” Stories, Essays & Memoir. New York: Library of American, 1998. 781–96.

Sister Uses Her Head

Story by Topher Payne

Portrait by Natalie Minik

Ghazal for Welty

Ghazal by Caroline Keys

Illustration by Molly Rose Freeman