Sister Uses Her Head

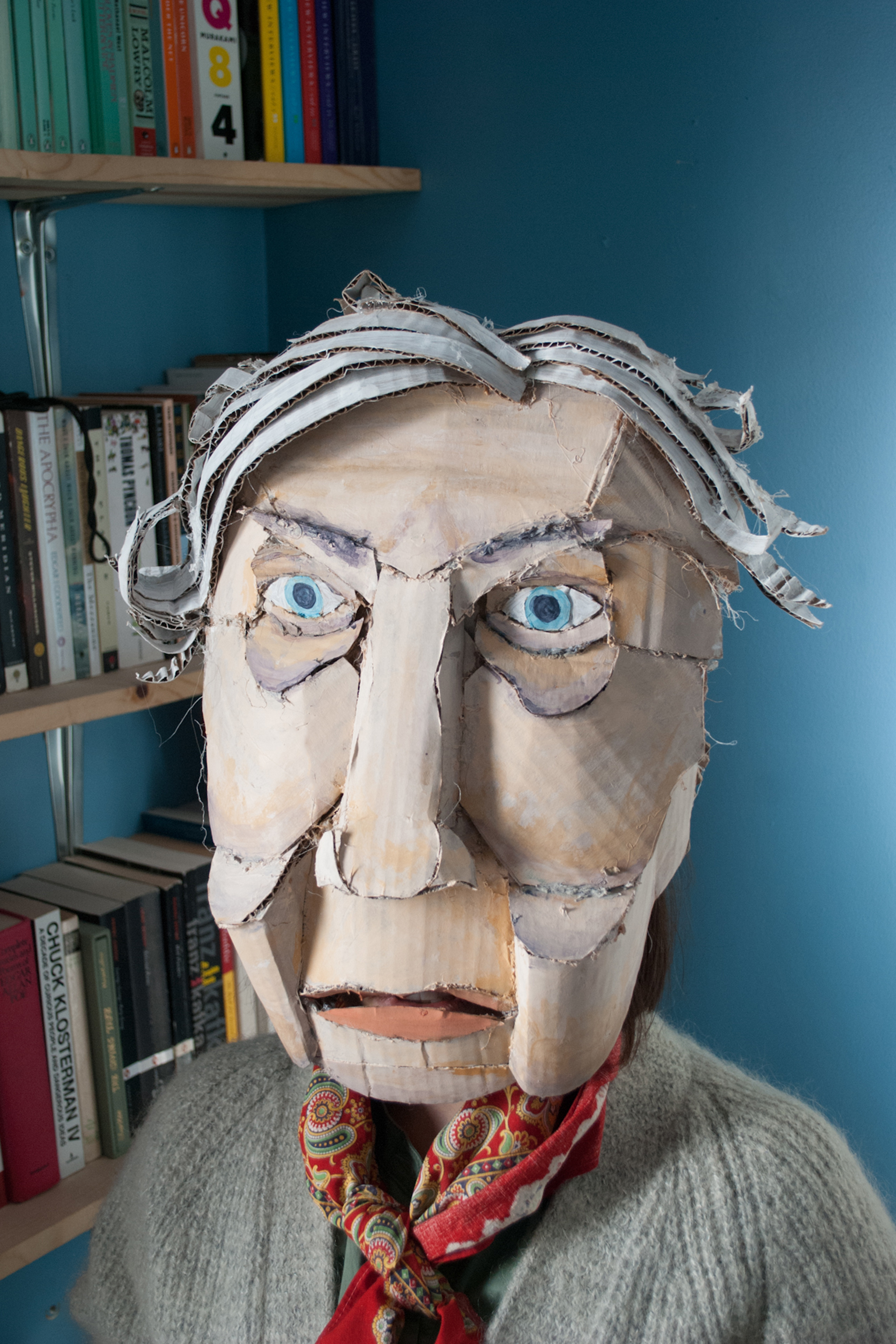

Story by Topher Payne | Portrait by Natalie Minik

Our kitchen is dark all the day long. The house itself is massive and smug — built by people with plenty to prove. When you grow up poor, as Mama and Daddy certainly did, there’s no end to the lengths you’ll go in announcing you’ve arrived. But there’s no reasoning with the newly wealthy, flush with the delight of bills paid and pocket money to spare. Some say poverty breeds character. Not true. Poverty breeds desperation.

So a Big House was erected out on a county road, more house than a family of four would ever need. Daddy, guilty for his extended absences on an oil rig, indulged Mama as she lolled about in magazines designed to make you feel about your home the way brassiere ads are designed to make you feel about your body. I wish you could have heard her wail with pleasure at the dark walnut cabinetry, the black granite floors and counters. The single skylight to, in her words, “make it cheerful.”

The resultant room has the feel of a dark clearing in a forest, where trolls and bandits lie in wait. But on clear days, a ray of sunshine stumbles upon the skylight for about 40 minutes, casting a lonely beam onto the Maytag dishwashing machine. One could fair expect the gleaming black Maytag to launch into a softshoe routine or sing a few verses of "John Henry," anything to justify its daily spotlight.

My two points here being: Our kitchen is quite dark, and Mama is a silly person.

My sister Anna Grace is silly by equal measure, pretty and curvy because she took after Mama. I’m resourceful and whip-smart, because I took after nobody. My presence in the family befuddles all four of us. Or three, now with Daddy in the ground. Presumably, Daddy is now befuddled by much larger notions.

The three of us, the females he left behind, are gathered in the tomb of a kitchen to discuss the serious matter Anna Grace laid at my feet last night, interrupting the brushing of my teeth. I am particular about my teeth. My extended relations serve as cautionary reminders of the importance of such things.

“Sister, I am in a state,” she’d said, breathlessly. Anna Grace is perpetually gasping for air, a catfish flopping in a bucket. I truly worry one day she’ll distract herself and forget to breathe, and that’s how she’ll meet Jesus.

“I believe Boarder Benton tried to come after me,” said Anna Grace.

“When?” I asked.

“Last night, on the davenport,” she fluttered. “I fell asleep watching my program, and I awoke to find his hands on my legs. Up high. And creeping higher.”

“Did you ask him what he was up to?”

“Yes, he said his hands were cold. But you know something, Sister? I have my doubts about that.”

Anna Grace is 16, two years older than me. And buck stupid. But even she wasn’t fooled by the shenanigans of Boarder Benton.

The first thing you should know is that Mama had no actual need for taking in boarders after Daddy got killed. Men who work on oil rigs always have real good policies, because it’s fairly expected some travesty will befall you out there. There are more ways to get killed on an oil rig than there are fish in the sea. Daddy used to make sure his good suit was pressed before he left to do a stint, just so nobody’d have to go to much trouble if he got sent back a corpse. Folks generally don’t have concerns like that if they work, as an example, at the supermarket.

But Mama was poor once, she would not be poor again, and she had no intention of finding a job. The dirt hadn’t settled on Daddy’s casket before she’d placed an item in the Hinds County Gazette advertising rooms for let with supper included. A person can take on up to three boarders at a time before someone from the courthouse comes along to cause trouble, and that is a blessing, because I swear Mama would have us overrun as an anthill if she could get away with it.

“Mama, do you suppose it’s wise, all these strange men comin’ and goin’?” I’d asked when the first boarders came shambling into the Big House.

“I do, Sister, I find it quite wise. There are things we women cannot do for ourselves, and it will be good to have gentlemen about.”

Mama was raised with an ever-expanding list of that which women cannot do, and she was more than happy to believe it because doing so kept her hands free. I read that in Spain all objects are either male or female. Mama would likely be quite happy there, having everything spelled out like that. (I am a voracious reader, and far too wise for my age. Everyone says so, and if they don’t, I do.) According to Mama, gentleman tasks include: the killing of bugs and flipping of pancakes, concerns regarding plumbing or automobiles, and fiddling with anything which plugs into the wall. Lady tasks, as far as Mama is concerned, have yet to be determined.

Mama’s own Mama—whom we called Mrs. Calloway, per her insistence—was not handsome in the slightest, but very well-maintained. It is a tragedy Mama didn’t take after her, even in some small way. Mrs. Calloway was a wise old crone, the lead teller at Merchants and Farmers Bank. If you came to make a withdrawal from your savings, she’d expect you to explain yourself. Then she’d decide whether you got to have your money or not. Occasionally folks would raise protest, but she had a way of explaining things so that you saw that her point of view was the only one worth considering. Anna Grace and I both feared and revered her ’til the day she died, and to this day speak of Mrs. Calloway in hushed tones.

So, here we are, listening to the hum of the ENERGY STAR Frigidaire, as Anna Grace haltingly relates the story of Boarder Benton’s wandering hands. I am present because I am nothing if not a supportive sister, and I also wish to see the look of unmitigated horror on Mama’s face as she realizes she has unleashed a passel of predators into the home she shares with her teenage daughters, one of whom is fetching and slow-witted. (The things that could have happened! And have! And could still!)

Mama’s lovely face becomes sour and crestfallen in a way I thought I would enjoy very much more than it turns out I do.

“Anna Grace,” she says at last. “I am dead curious to know how you came to be in a position for Boarder Benton to interfere with you in the first place.”

Interfere, like he’d prevented her from passing him on the sidewalk or opened a certified letter.

“Honey, your face and your shape will take you plenty far if you use it proper. But you really can’t allow yourself to be put in that sort of situation. You’re lucky he didn’t try to take full advantage.”

There is so much to explore and peruse in Mama’s words. Apparently Boarder Benton warming his hands on the inside of Anna Grace’s thighs is considered advantageous for him, but only partially so.

“Mama!” I wail, in shock. I am stunned. “You’ve got to do something about this! There is a wolf in this house!”

“Anna Grace,” Mama continues, swatting me away like a mosquito. “Boarder Benton will be dealt with. But it’s important you understand: You’re near grown, and the world is not safe for pretty women. Friendly, certainly, but not safe.”

Anna Grace just sits there, brow furrowed, lips pressed tight as a clamshell, trying so very hard to understand what Mama’s getting at. She knows all the facts of life—cousin Caro explained the ins of the birds and the outs of the bees to us when we were ittie bitties in such shocking detail that I swore off any interest in the enterprise. Anna Grace knows where babies come from and what feels nice and why. But no one has explained to her that some man might wish to feel nice with her, whether she wants to or not.

“Anna Grace!” I blurt. “Breathe!”

So she does. You see how I have to remind her?

“Mama,” Anna Grace finally whispers. “What do you mean?”

“We won’t say another word about it,” says Mama, wiping her hands on a dishtowel like Pontius Pilate himself. “It isn’t ladylike to discuss prurient subjects.”

I make a mental note of that, adding it to Mama’s list of things ladies cannot do. You’d think the list were made of kudzu, how it forever grows.

“Now. I suggest we treat this as an unpleasant memory, which we will fold up inside ourselves and forget about completely, as we do with all unpleasant memories.”

Did I tell you Mama hasn’t allowed us to mention Daddy since the day we buried him? She says we shouldn’t dwell on sad things. I feel like you should know that about her.

Day turns to night in the Big House, and when we’re called for supper, who should come waltzing to the table like the star attraction but Boarder Benton himself! Anna Grace is, as one would expect, breathless. He reaches for the basket of Brown ’n’ Serve rolls, but I snatch them away.

“Boarder Benton,” I say. “You ask permission before you put your icy mitts on someone’s bread basket!” (You see how that statement works on two levels? And I just thought that up right there on the spot.)

Well, before I can even take pleasure in his shocked-stupid face, Mama has led me by the hair into the kitchen, where she proceeds to lay out an elaborate tale of financial hardship that is true only in her vainglorious mind. She tells me Boarder Benton has been thoroughly chastised for his unseemly behavior, and is quite certain there will be no further incidents under our roof.

Well, now she has gone and done it. These hoboes are all in cahoots, you know. At the first chance, if he hasn’t already, Boarder Benton will take the little prepaid telephone with the cracked screen from his pocket and commence to tapping. He’ll tap to all the vagrants in Mississippi, likely Louisiana trash across the river too, that here in Bolton they’ll find a bounty of temptation, and not a single consequence for sampling however they wish. Mama’s benign neglect will smut Anna Grace out by summer.

I am without words, seething as I am with fury for the conceited fool charged with raising me. I excuse myself from the supper, having lost my appetite for food, for Mama, and for the whole misbegotten world.

Shortly, Anna Grace joins me in my bedroom, on a fact-finding mission.

“Is it true what Mama says? That the world isn’t safe for a pretty girl?”

I give this due consideration. As much as I am loathe to agree with Mama, I will concede she has a point. Folks talk of pretty girls as they would a horse — length of leg, quality of mane, suitability for breeding. A pretty girl in a Mississippi town is an object to covet, something for a family to barter in their ceaseless quest for better and more. That’s all Anna Grace is, really. A playpretty we endeavor to keep unspoiled, until it is decided to whom she will be bequeathed. Only ugly women get respect around these parts because it’s assumed that if God was cruel to you with one hand, he must have blessed you with the other.

These are the things I think. What I say is, “Supposing it is true, what do you intend to do about it?”

I have asked Anna Grace to think for herself about what she wants and what she deserves, so the protracted silence that follows is not at all surprising.

“I would be so happy . . . ” she begins, then has no idea how to finish. “I wish I were an old crone. With droopy eyes and sagging cheeks. Sister, I wish I were so ugly that people cared what I had to say.”

For the umpteenth time today, I am lightly stunned.

“Well, Anna Gee,” I reply, using the name I haven’t called her since we were babies. “What would you like to say?”

“I don’t know, Sister. I’d just like the option.”

In this moment, there is nothing in this world I am more certain of than my determination to give Anna Grace exactly what she wants. (I am, as I told you already, a most devoted sister.)

We pull a heap of discarded boxes from the blue rolling bin out in the carport. Anna Grace dusts off the conjoined pots from a long-forgotten paint-by-numbers set. We set about our task, of one mind, cutting and coloring and gluing, until it begins to emerge: a face, looming and large, like the grandmother of one of those Easter Island statues.

We have constructed for Anna Grace a mask of authority—something to protect her from her prettiness in a house filled with danger. Were I to be objective on its aesthetics, I would call it interesting and crude and wise, everything a woman aspires to be but cannot begin to imagine how. The head slips right over Anna Grace’s own, like a space man’s helmet. She looks in the mirror, doesn’t make a sound.

“Anna Grace, can you breathe in there?”

“Yes, Sister. I can,” and to prove it true, she fills her lungs with the deepest breath I’ve ever heard from her, then expels a long, contented “hoooooooooo.”

“Boarder Benton won’t be touching me again, Sister. I’m a wise old crone and I won’t stand for it.”

Anna Grace’s words are prophetic. She’ll take to wearing that head around the house for the remainder of springtime, delighting both in the wide berth she’s afforded by boarders and especially in the horrified reaction from Mama, who will plead with her to remove it. Anna Grace will reply that she’s only trying to keep herself safe, a pretty girl in a dangerous house, as Mama had advised. After months of this, Mama will steal into her room late one evening, take the head, and burn it on the refuse pile. But Anna Grace won’t give her the satisfaction of a fit about it. That head will have already served its purpose: It will have given her time to think, time to discover she has a right to.

Within a year, she’ll leave the Big House and never return. I’ll follow in her wake a little bit after, and Mama will become an unpleasant memory we fold up inside ourselves and forget about completely. Anna Grace and me, we will go out into the world and become wise old crones.

I can see all of this, as I stand beside my sister at the mirror, watching her find her breath for the very first time.

The Wolf Groom

Story by Laura Relyea

Photo by Mandy O’Shea

Seeing Eudora Welty Seeing

Story by Pearl McHaney

Illustration by Natalie K. Nelson

Ghazal for Welty

Ghazal by Caroline Keys

Illustration by Molly Rose Freeman