Brothers, the Blues, and the Decisive Moment

/Story by Scott Sharrard

Photo: Patricia O'Driscoll

On August 23, 2008, I got a call at my Brooklyn apartment in the early afternoon from my friend Jay Collins. The “audition” had finally arrived.

After a couple years of trying to find the right time, Jay could green-light a chance for me to sit in with the Allman Brothers, the band I had admired and loved above all others since I was a little kid. To me, they were the blueprint for what rock and roll could be at its best. And to have the chance to share the stage, let alone have a shot at playing in Gregg Allman’s solo band, was a unique opportunity. I considered Allman to possess the greatest voice in the history of rock and roll.

Rolling into Camden, New Jersey, that afternoon with Jay, I came to meet the band one by one. They were a gracious bunch, and Gregg embraced me immediately. I think he sensed my deep love for the blues. Soon after that night we began our journey in “his band,” the Gregg Allman Band. We traveled all over the world for those first couple of years, and a musical bond was steadily growing between us. In 2015, he made me his band leader and had already begun covering one of my own songs, “Love Like Kerosene,” which appeared on Back to Macon Live and eventually our last album, Southern Blood. That was an honor in itself.

But then one day he asked me to write songs with him, and in that moment, the journey had really just begun.

One night, after an exhausting day of writing and hanging at his house in Savannah, I woke up suddenly from a vivid dream. It was one of those dreams where you bolt out of bed and have several scenes replaying over and over in your head like a movie. I scrambled for my pen and paper and wrote down the first verse and the hook line to what would become our song.

You and I both know this river will flow to an end,

Keep me in your heart and keep your soul on the mend.

You and I both know the road is my only true friend.

In my dream, I had seen a young Duane Allman speaking those words to Gregg.

As I scribbled the words down and saw them land on the page like a transcription from my dream-consciousness, I was almost shaking. The song was here and my dream conversation between Duane and Gregg had delivered the first batch of lyrics. I ran downstairs and grabbed an acoustic guitar. The sun was coming up over the Georgia swamp, and it was laying a dull light across Gregg’s yard and down to his boat slip. By coincidence, they used almost the exact same image for the cover of Southern Blood. To my knowledge, no one knew of my story when that photo was chosen.

I started playing the guitar and the intro spilled out while the words flowed into the melody. This was what we all wait for as writers, what the genius photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson referred to as " the decisive moment,” when that perfect shot lines up, and the impossible image is captured, a universal truth gets caught and preserved for the world. When Gregg woke many hours later, I showed him what I had. He knew immediately this was gonna be the song.

Fast forward to later that spring. Gregg was at the Beacon Theater in New York City for an run of Allman Brothers shows. I had scheduled time with him in his hotel and showed up in the early afternoon. Gregg was always a great host, and he had a laugh that haunts me to this day. It was infectious and beautiful. He had a gentle but commanding presence that also yearned to open up and hang loose.

But this day was different. Something hung in the air as I stepped into his suite. He came out to greet me, the shades pulled and the atmosphere dark. I waited for him to speak. He leaned forward without being able to look me right in the eye and told me he had terminal cancer and might have only eight months to live (he defied the odds and pulled off another couple years). We both teared up, and I tried to gather myself. I was his guitarist, band leader and writing partner. But in this moment, I became a musical shepherd and a friend. The weight of the task at hand was now clear.

Gregg insisted we work. Music was his lifeblood, and it was time to let some drip on the page. As we crafted and turned the lyrical phrases and changes over and over for our pre-chorus, he suddenly stopped. He reached his hand over and scratched out everything we had worked on up to this point for that pre-chorus section. I braced myself. And then he wrote — in that fluid, military school-trained handwriting of his — the words that would pull the song into focus.

I hope you’re haunted by the music of my soul when I’m gone.

There it was again: the decisive moment. Right, I thought to myself, this is the song we are writing. The goodbye letter.

Time wore on, as it does in life and in the fickle, frantic world of the music business. Don Was came on board and the three of us crafted ideas for a record. “The song,” as I had begun to think of it, worked its way into our nine-piece band. After many rehearsals and private trial runs, Gregg was sure it wasn’t ready.

Then, the day finally came when we stepped into the legendary FAME studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, and began cutting. However, that song was not making it into our workload. I confronted Gregg at one point; I knew his interests could shift and that he would sometimes let important moments slide. Over his lifetime, his brother Duane, producer Tom Dowd, and Warren Haynes had all played big parts in helping to circumvent and regulate this side of Gregg — the part of him that would shy away from work or hold back.

This was, of course, a key part of Gregg’s brilliance. His reductive qualities made him a laser-focused performer and creator in the moment. But Gregg’s occasional downfall was that his deadlines and details would often not line up. This slowed down progress time and again, and when you add in a life-or-death health struggle and a grueling tour schedule, it was often hard to keep the focus where it ought to be for recording an album.

No matter: We had percussionist Marc Quinones in the Gregg Allman Band. We called him “the general.” Marc was instrumental in so many aspects of our band. Gregg loved this man so much, and I do, too. He’s a great mentor and friend and a brilliant musician. When Marc speaks, I listen.

I went to Marc and I said, “Look, man, I don’t think Gregg wants to cut this song. He says it’s not finished. Here we are doing the album and this important song that he had a hand in writing may not make it. What the hell should I do?” Marc thought about it and then came to me with the idea of a third verse. To this stage, there had been only two.

Beside myself with frustration, I went back to my room at the Marriott Hotel that night and started scribbling. Could there be, I asked myself, one more decisive moment? I was frustrated and tired. And out of that feeling came the third and final verse.

Still, on and on I roam,

It feels like home is just around the bend.

I've got so much left to give,

But I’m running out of time, my friend.

The lyric could just have easily been me talking about getting the song finished and recorded for the album as it could have been about Gregg’s life running out of time. But Bresson had struck again. In a flash, I knew the song was done. The final decisive moment.

The next day I came to Gregg with the new verse hand-scribbled on his lyric sheet. We always had a sympathetic working dynamic, but it could be shot through with tension. I was apt to shoot from the hip and relentlessly chase the muse. In contrast, Gregg was a patient and thorough creative soul, content to tease out the magic and pick his spots.

I never worked up the nerve, even in my last visit with him weeks before he died, to share the Duane dream story. In a way, that was obvious: We talked about Duane every day. I did ponder sharing the intensity of that initial inspiration and using it as motivation for this important moment, but something told me to hold back and let the new, third verse speak for itself.

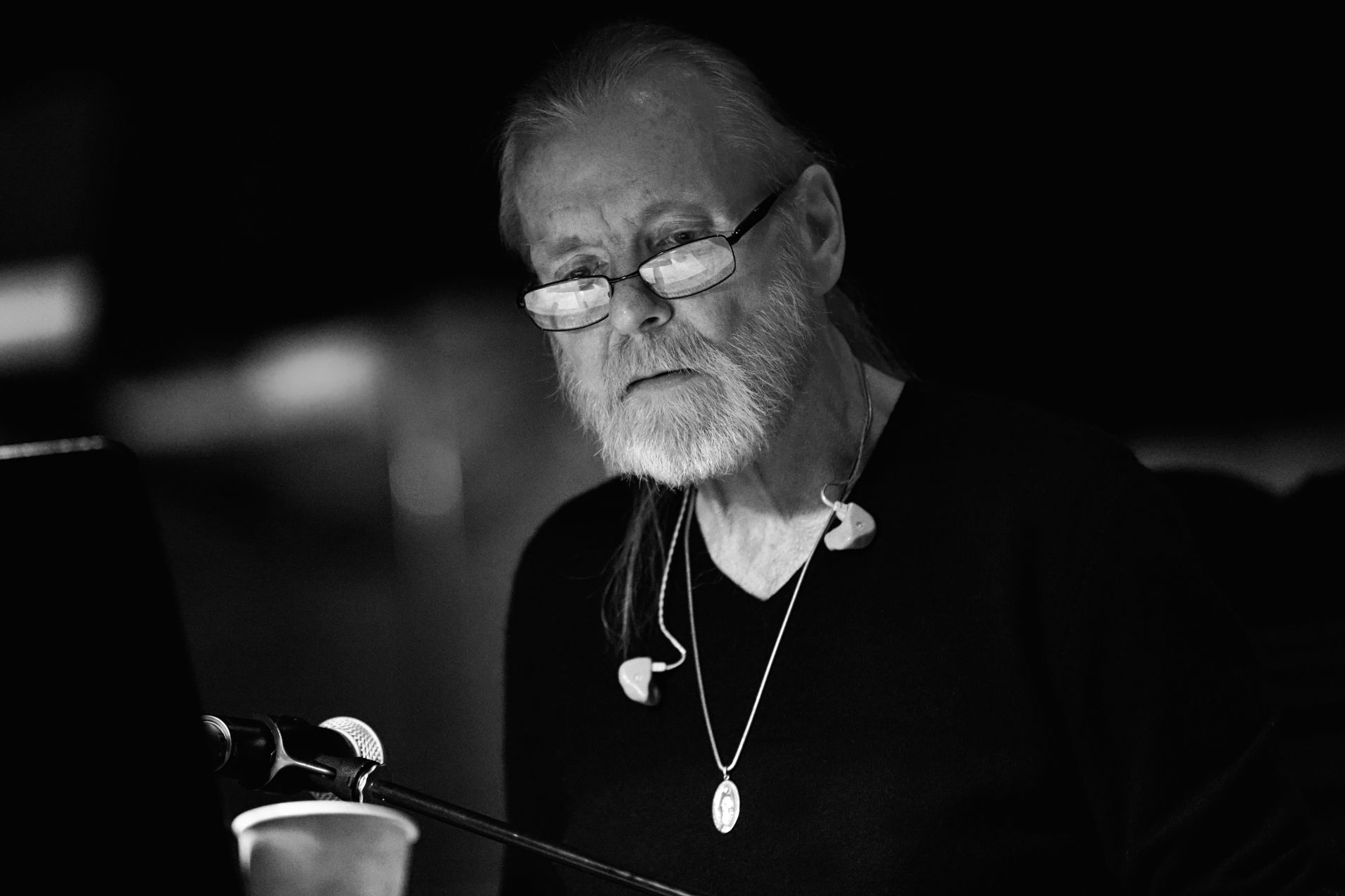

For those who really knew Gregg, he had a way of pressing his fingers to his lip in concentration and gazing downward at the paper clutched in his hand. Swaying back and forth, his jewelry jingling a little from his neck and tattooed arms, the quiet storm of creation and interpretation brewing.

Finally, he looked up, peered over his reading glasses, and said, “Okay, let’s cut it.”

Gregg passed away in May of last year. In the fall, we were nominated for two Grammy Awards — one for Americana album and the other for Americana song of the year. Our years-long work in progress that almost didn’t make the record was in the final five to be that song. I agreed to do press for the album and told my story, specifically that journey to make Gregg’s last will and testament in “My Only True Friend.” But most the press never really grabbed the narrative, and we quietly ushered our way into February of 2018.

The afternoon ceremony at the Grammys is where they give all the awards to the tributaries of rock and roll — the blues, jazz, country, folk, and classical music the telecast was built on. There are no explosions or costumes. Just musicians putting blood on the floor, protecting and pushing the boundaries of tradition. The afternoon ceremony, with the cameras off, is where the real stuff happens.

As we waited for the category of Americana to come up, I heard my friend and mentor’s voice in my head.

“Americana, huh? So, that’s what they call rock and roll these days!”

I wished he was there in the worst way.

Gregg always wanted to move out of his brother Duane’s shadow. This seemed like his graduation day, the acknowledgement and affirmation he would finally get from his peers for his vision and his final love letter to the world, which we had carved out together. But now, it was just me here to accept my part of the honor and Gregg had become a creative phantom limb. It was hard to not focus on this feeling of abandonment as the ceremony carried on.

Right before they announced our awards, the room darkened to a red glow. Taj Mahal and Keb Mo took the stage with their Dobro guitars. Taj was a close friend and mentor to Gregg, and he had given Gregg a Dobro I got the chance to play on the “Southern Blood” album. Both Taj Mahal’s and Keb Mo’s records played constantly on the Gregg Allman tour bus. I remember many times when I would catch Gregg staring long and hard out on that endless road, in the middle of the night, as the wheels rolled beneath us to the rhythm of the blues. This was the pulsing soundtrack to our late-night drives past the corn fields and through the mountains, heading toward our next show, rolling on that long and lonesome road.

Blazing out west to the poetry of Taj’s gravel-soaked moan and the sweet pluck of that Dobro, I started to tear up. The timing of this performance was poetry to me. The room seemed to go from red to purple as the blues set in. Keb was working some slide guitar, and all the tributaries came together. I took this as a sign there was something deeper to tune into.

I turned to my wife and whispered, “Gregg is here.” As they finished the song and the pregnant pause hung in the air between the last notes of this haunting music and the awards announcement hung, Gregg’s voice echoed through my head:

“It’s all right, Scotty. Nothing matters but the blues.”