A Hole in the Heart of Georgia

/Story by Steve Oney

During the broiling days of late July and early August, heavy equipment operators demolished a decaying but incongruously lovely redbrick building just outside the antebellum town of Milledgeville, Georgia.

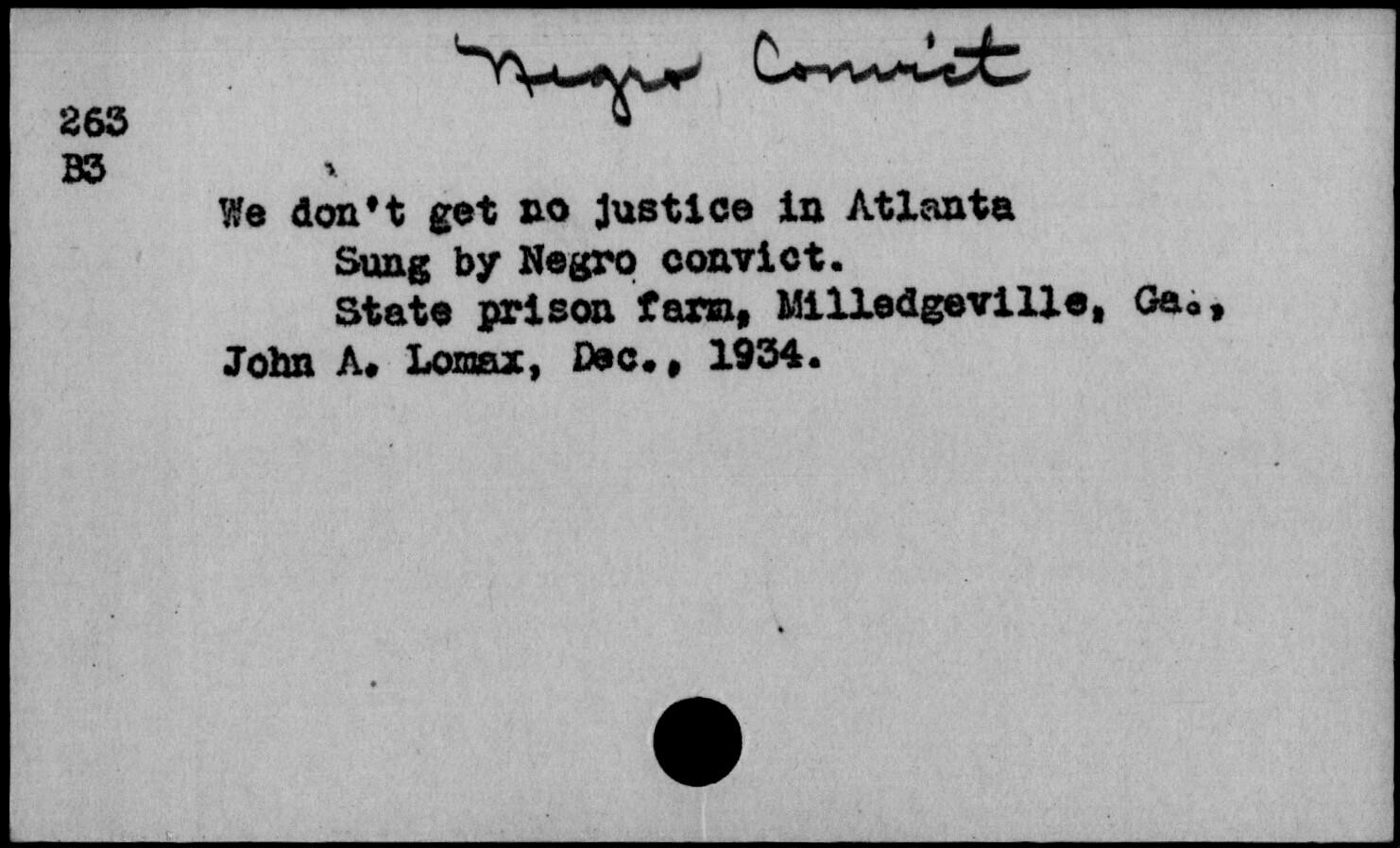

The 107-year-old structure, which was fronted by a columned portico and graced by arched windows, served from 1911 until 1937 as the dormitory and offices of the State Prison Farm, site of Georgia’s first electric chair (“Old Sparky”). Corn and cotton fields worked by inmates in stripes once surrounded it. An early prisoner was train robber Bill Miner, who coined the phrase “hands up.” In 1934, black inmates gave recorded performances on the grounds as part of a pioneering scholarly effort to document the roots of blues and gospel music. The place was sufficiently historic to qualify for the National Register. But what makes its destruction, carried out at the order of the Baldwin County Commission, an outrage is that the facility provided one of the few remaining physical links to a still-relevant anti-Semitic atrocity that changed not just the South but America.

Around 11 p.m. on the night of August 16, 1915, a handful of armed vigilantes from Marietta, Georgia, burst into a tiny room at the front of the Prison Farm dormitory. Leo M. Frank, a Cornell-educated Jewish industrialist whose 1913 conviction for the murder of Atlanta factory girl Mary Phagan had become a nationwide cause célèbre, was recuperating there from a knife wound inflicted by a fellow inmate. The invaders grabbed their man – clad only in a white, monogrammed nightshirt – by the arms and legs and dragged him onto the porch and down a set of stairs to a caravan of waiting cars, one of which contained a hemp rope, the business end already tied into a hangman’s noose.

Traveling by a circuitous route that ran well to the east of Atlanta and possibly as far afield as Barrow County on the edge of the Piedmont, the party drove some 150 miles north, reaching Marietta at dawn. There, at Frey’s Cotton Gin, the group looped the rope over the limb of an oak tree, slipped the noose around their captive’s neck, placed him atop a waiting table, and kicked it out from under him. Twenty-two lynchings occurred in Georgia in 1915, but none had the impact of the lynching of Leo Frank. The crime helped resuscitate the Ku Klux Klan (the hooded fraternity, disbanded after Reconstruction, came back to life at a cross burning on Stone Mountain that autumn) while simultaneously jump-starting the just-founded Anti-Defamation League.

The first time I visited the State Prison Farm in Milledgeville was in the fall of 1997. My guides were Jake and Sonny Goldstein, local businessmen (both, sadly, now dead) with deep connections to the Middle Georgia Jewish community. By this point, it had been 60 years since prisoners were confined to the place, and the corn and cotton fields had been transformed into a giant auto salvage yard. Yet despite the constant rumble of machinery ripping apart and crushing metal, I was immediately transported to 1915. I was a decade into the research for a nonfiction book about the Frank case. I’d burrowed into every archive and spoken to all the kinfolk, but not until this instant had I walked the same ground trod by many of the principals.

In what had been the office of Warden J.E. Smith, I stood where Frank had during an interview with documentary filmmaker Hal Reid, who came to Milledgeville shortly after Georgia Governor John Slaton commuted the convicted man’s death sentence to life behind bars. Reid’s picture — prosaically titled Leo M. Frank and Governor Slaton — played to packed houses in New York. (“First you were talking with Mr. Reid,” Frank’s mother wrote her son. “Then ... you were standing talking to Warden Smith; he turned and looked out the window and pointed.”) In a room that had served as the prison library, I could almost hear the voice of Metropolitan Opera star Geraldine Farrar on the records Frank played on the prison phonograph. In the open space where most inmates bedded down, I knelt at the spot where Frank was sleeping when a convict named William Creen raked the knife across his throat. Frank survived because Dr. J.W. McNaughton, a Swainsboro physician doing time for the murder of his mistress’s husband, stitched up his jugular vein.

These locations brought Frank’s final months into focus for me in a way that no amount of reading could have. But another, less obviously dramatic section of the prison dormitory spoke even more powerfully to me, clarifying how a mob could have broken into a state institution and abducted the most famous inmate in America without firing a shot, which is what happened.

When Frank was incarcerated in Milledgeville, the place consisted of only one massive wing. In late 1915, a second wing, mainly for black inmates, was constructed. The so-called new wing, which I walked from end to end, was financed by the Georgia legislature as a payoff to prison officials for looking the other way the night Frank was seized. John Tucker Dorsey, a Marietta lawyer, was chairman of the House Penitentiary Committee. He was also one of the masterminds of the lynching. He used his political position not only to threaten the men in charge at Milledgeville (a typhus outbreak had taken three lives in early 1915, and blame could have ended careers), but also to reward them. Just weeks after Frank’s death, the legislature appropriated $30,000 for construction.

In other words, the Prison Farm was both a crime scene and a piece of physical evidence. The brick and mortar in the new wing testified to Georgia’s role in Frank’s demise. Seeing it confirmed everything I’d discovered in documents. This was an inside job that went to the top in Atlanta, and that’s what I wrote.

The last time I visited the State Prison Farm was in 2003. And the Dead Shall Rise (the title of my book) was due out in a couple months. I’d driven to Milledgeville with John Pruitt, a veteran Atlanta news anchor, producer C.B. Hackworth, and camerawoman Leona Nascimento. To coincide with my work’s publication, WSB was preparing a special. As John and I traipsed around the facility talking, C.B. and Leona got it all down on film — no small task, as the salvage yard was still in noisy operation.

During the six years that had passed since I’d last been there, the building had suffered a lot of damage. We had to watch our steps to avoid holes in the floor through which we would have plunged into the basement. Shafts of light poured down from openings in the roof. The place did not seem long for the world. In the room where Frank stayed the night before his death, an industrial glass door shot through with chicken wire had fallen off its hinges, spraying shards everywhere. I picked up a small piece and put it in my pocket. The next day, I telephoned Sandy Berman, then the archivist at the Breman Jewish Heritage Museum in Atlanta. She acquired the door for an exhibit on the Frank case. Along with my little shard — and Old Sparky, which was long ago moved to Georgia’s current prison in Reidsville — that’s all that made it out.

Baldwin County took control of the Prison Farm property when the salvage yard closed. Its argument for razing the facility emphasized that it was a liability and would have cost $5 million just to stabilize. (The bill for actually restoring the place would have run higher.) There is undoubtedly merit to the commission’s position that demolition was a sensible option, although the body failed to hold hearings or notify the public of the impending action. Simply put, less drastic alternatives were never fully discussed.

To members of a Prison Farm Facebook page founded by Edwin Atkins, grandson of the facility’s former chaplain, the decision to take the building down was hasty and short-sighted. At a moment when the South’s contested history has become a source of growing interest — not to mention revenue — the Milledgeville prison could almost certainly have qualified for grant money and attracted donations from benefactors, especially those interested in the Frank case, which has inspired a Broadway musical and a television miniseries. It remains one of the most intriguing criminal mysteries of the 20th century and a touchstone for students of Jewish history.

Increasing the likelihood that funds could have been secured to save the Prison Farm was its significance to African-Americans. As most who’ve studied it agree, the Frank case turned on a dual form of intolerance — religious prejudice against Frank and racism against Jim Conley, the state’s key witness, who was black. A majority of historians believe Conley murdered Mary Phagan. Desperate and cunning, he pinned the crime on the Jewish Ivy Leaguer. The saga unfolded against a backdrop of ugly taunts and slurs all around. Milledgeville, however, offered a potential setting for reconciliation.

When John Avery Lomax, the great musicologist whose son Alan famously followed in his footsteps, set up his tape machine at the State Prison Farm in the early 1930s, many black inmates there could still remember Leo Frank. His fate was no different than that inflicted by Judge Lynch on a procession of their brothers. The songs Lomax recorded speak to a common humanity. Performed by inmates identified merely as “negro convict on guitar with sound of dancing” or “negro convicts,” the numbers include such prison blues as “We Don’t Get No Justice in Atlanta” and “Stock Time.” Others, among them “One Mo’ Train,” express a universal longing for freedom. Most, though, are religious and beseech a God who does not see race or heritage: “Sin No More,” “Po’ Laz’us,” and “Oh Lawdy Me, Oh Lawdy My.”

Lomax’s tapes are in the permanent collection of the Library of Congress in Washington, where anyone can listen to them. As I ponder the destruction of the place where those recordings were made, I’m saddened there will never be the chance to play them in Milledgeville and bring people of all colors together there to discuss not just what they share but the importance of the past. By confronting the legacy of injustice — and there was no greater injustice than lynching — Southerners can move beyond it. The lesson — and the hope — of the South is that from darkness comes light. The Prison Farm was a spot that could have encouraged that belief.

The Baldwin County Commission says it plans to erect a historical marker on the site, but the gesture seems woefully inadequate. The building where Leo Frank was given over to a mob and black inmates raised their voices in songs of lament and praise was itself the monument, and now it’s gone.

Steve Oney is the author of “And the Dead Shall Rise” and “A Man’s World: Portraits.”