In a town known for its beer, artisanry, literature, and the Biltmore, there’s a known yet unassuming theme, an undercurrent, uniting them all. Writer Wiley Cash explores how Asheville’s climate also serves as an anchor for national and global weather research.

Words by Wiley Cash | Photographs by Mallory Cash

Although Asheville, North Carolina, is a relatively small city of a little over 90,000 people, it’s easy to spot the many features that make it so attractive to visitors and residents alike. South of downtown, Biltmore Estate has been inviting people to tour America’s largest privately owned home for decades. Beginning with Highland Brewing in 1994, breweries like Sierra Nevada, New Belgium, and Oskar Blues have flocked to Asheville and the surrounding area, making it the official Beer City of the United States. Since 1982, Malaprop’s Bookstore and Café — where you’re as likely to find major bestsellers on the shelves as you are to bump into the authors who wrote them — has kept downtown Asheville weird while also keeping it on the literary map.

Outside the city, it’s easy to spot the geographic features and feel the cool summer temps and relatively mild winters that brought an onslaught of visitors around the turn of the 20th century. George Vanderbilt decided to build his country estate after glimpsing Mount Pisgah from one of the Battery Park Hotel’s grand porches. Edwin W. Grove decided that Asheville’s Sunset Mountain would be the home of the iconic Grove Park Inn because he found the climate good for his health. Legend holds that in decades past and certainly in decades that would follow, moonshiners and brewmasters alike settled on the area because of the quality of its abundant water.

But regardless of whether you’re a visitor or a resident, what is harder to see are the people who track the changes in that temperate climate that drew Grove to the area, who protect the wild spaces like those where Vanderbilt decided to break ground, and who show us the true value of the places that have long made Asheville a destination.

There are two things you need to know before we begin: First, this is a story about looking and seeing and discovering something that might surprise you. Often what surprises us is as obvious as an enormous mountain looming in the distance or as invigorating as a cool snap on a July evening. But just as often, what might surprise us is less visible: the paper relic of a 19th-century weather report buried in a centuries-old archive; the incredibly nutritious dandelion leaf that is usually overlooked as a weed; a world-renowned climate scientist sitting in the brewery at the table next to you, enjoying a pale ale while gazing out at the French Broad River. The second thing you need to know? There are a lot of acronyms in the world of climate science.

Worldwide weather reports and climate data going back centuries are now housed downtown at the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) in the basement of the rather nondescript federal building on Patton Avenue.

For writer and preservationist Jay Leutze, living and working in the Asheville area has long been an education in looking and seeing. In 1994, Leutze, out of law school and fresh from a stint in business in London and Boston, settled in a rambling family-owned cabin in nearby Avery County in the hopes of writing a novel. Instead, he ended up writing a bestselling nonfiction book titled Stand Up That Mountain, about the experience of rallying the local community to stop a gravel operation that was destroying Belview Mountain. More important was the fact that the gravel mine could be heard from the Appalachian Trail, the blasting of rock and incessant roar of hydraulic machinery competing with the sounds of nature. Leutze and his allies stopped the gravel mine, and an Asheville-based preservation organization called the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy (SAHC) would go on to purchase and preserve one half of Belview.

When he wasn’t in court, in the community, or at his desk, Leutze was leading hikes to Big Yellow Mountain for SAHC, an organization he’d been aware of since its inception in 1974, when some of its earliest meetings were held in the living room of the cabin in which he now lives. The conservancy’s first project was to preserve the bald atop Big Yellow. Leutze’s parents were early supporters of SAHC, and Jay, who is now the conservancy’s senior adviser to the board and government relations director, literally followed — well, perhaps hiked is a better word — in his parents’ footsteps.

“When leading hikes, you have to tell a story,” Leutze says. He is standing on that bald atop Big Yellow, the world rolling away from him on all sides in endless swells. He admits that as a kid he did not know the full story of the bald, nor did the conservationists who set out to protect it 50 years ago. While the views are breathtaking, what’s underfoot is even more so, but you have to look closely to see it.

“As you get up here and walk in these grasses at high elevation, you’re not walking in a cow pasture,” Leutze says. “You’re walking in a relic landscape of the arctic climate regime.”

Jay Leutze stands atop Big Yellow Mountain. The bald is now managed by The Nature Conservancy and the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy (SAHC), where Leutze is the senior adviser to the board and government relations director.

At one time, this bald was browsed — not grazed, as Leutze informs me — by woolly mammoths, bison, and elk. The Cherokee called the area home for centuries, but after the American Revolution, the mountain was lost to them when a man named Waightstill Avery — an enslaver who would go on to have a hand in shaping North Carolina’s state constitution — took the property in a land grant. As state attorney general, Avery would eventually draft the treaty that ceded Cherokee land to white settlers.

Under an agreement Avery made with a local family named Hoilman, cattle were allowed to browse atop Big Yellow Mountain. The bald is now managed by The Nature Conservancy and SAHC, and by continuing the agreement with the Hoilman family, the conservancies ensure that cattle will do the work that for eons was done by fire, weather, and long lost prehistoric mammals. The cattle are not only important in keeping the bald clear, they also keep rare plants like oat grass and three-toothed cinquefoils alive and thriving.

“We have an arctic climate in North Carolina at this high elevation,” Leutze says. “The plant complex here doesn’t exist anywhere else on earth. These species were pushed into the South during the last ice age, stranding them as the ice receded to the north once the ice age ended. These arctic plants are cousins to those that still exist above the Arctic Circle, but they are genetically distinct because they evolved in our time, in our place, with our soil, in our weather.”

Animal species are also protected by the bald, especially the golden-winged warbler, which has faced severe population decline in the last 50 years. Big Yellow Mountain marks one of the southernmost breeding grounds during the bird’s annual migration from the midwestern and eastern half of the United States to Central and South America.

Leutze admits that one of the knocks against preservationists is that they only care about preserving spaces in their own backyards. While Leutze is primarily working on preserving spaces close to home, there is no doubt that these spaces have global implications.

Recently, Leutze hoped to find a way to conserve 900 nearby acres that were being sold by a family that lives in Raleigh. At stake was a particularly fragile landscape that features a cliff complex and a rare species of endangered plant — so rare that it is one of only 12 known populations in the world. But the money wasn’t there. Leutze and his team went to work, partnering with North Carolina State Parks to draft new legislation so that conservation trust funds could be used to purchase the land in the hope that it would one day become a state park. But they were too late. Funding in hand, he contacted the sellers and learned that he had run out of time. When Leutze discovered the identity of the new owner, he was shocked, and then he was worried. The 900-acre tract had been purchased by Tim Sweeney, a video game developer who would go on to become a billionaire after building Fortnite into a social network juggernaut.

Leutze dug around until he found Sweeney’s email address, and he sent him a neighborly hello, just two guys vying for ownership of hundreds of acres of land across the ridge from one another. Sweeney wrote back almost immediately. He was in South Korea on business, and he was actually reading Leutze’s book right at that moment in order to better understand the community where he now owned land. The two men spent the rest of the evening emailing back and forth, and Leutze soon came to understand that he and SAHC had a new ally. Like Leutze and everyone at the conservancy, Sweeney had the same concerns about preserving spaces where rare plants and animals are under threat. The only difference was that Sweeney had much deeper pockets and could move more swiftly to acquire land. So far, Sweeney has donated nearly 8,000 acres in the mountains of North Carolina, including the other half of Belview Mountain, which he learned about in Leutze’s book. The land Sweeney’s purchased fits into a contiguous block of tracts across Avery and Mitchell counties. Last year, on Earth Day, he announced that all of it will be transferred to the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy.

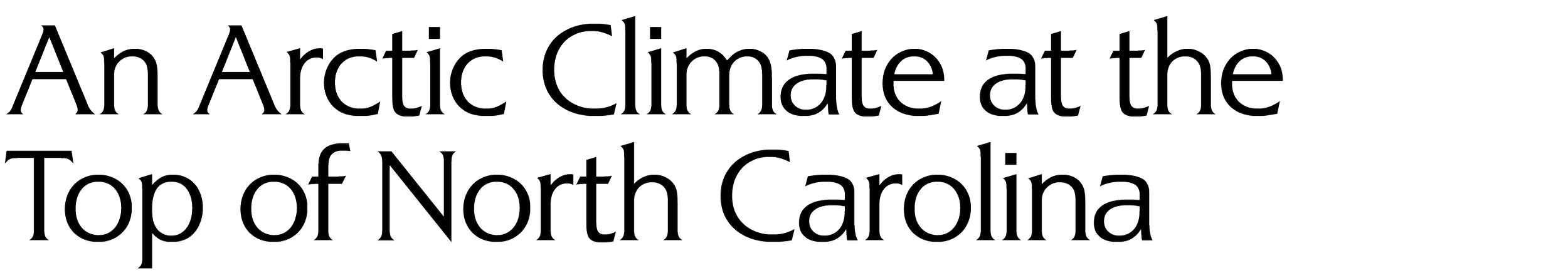

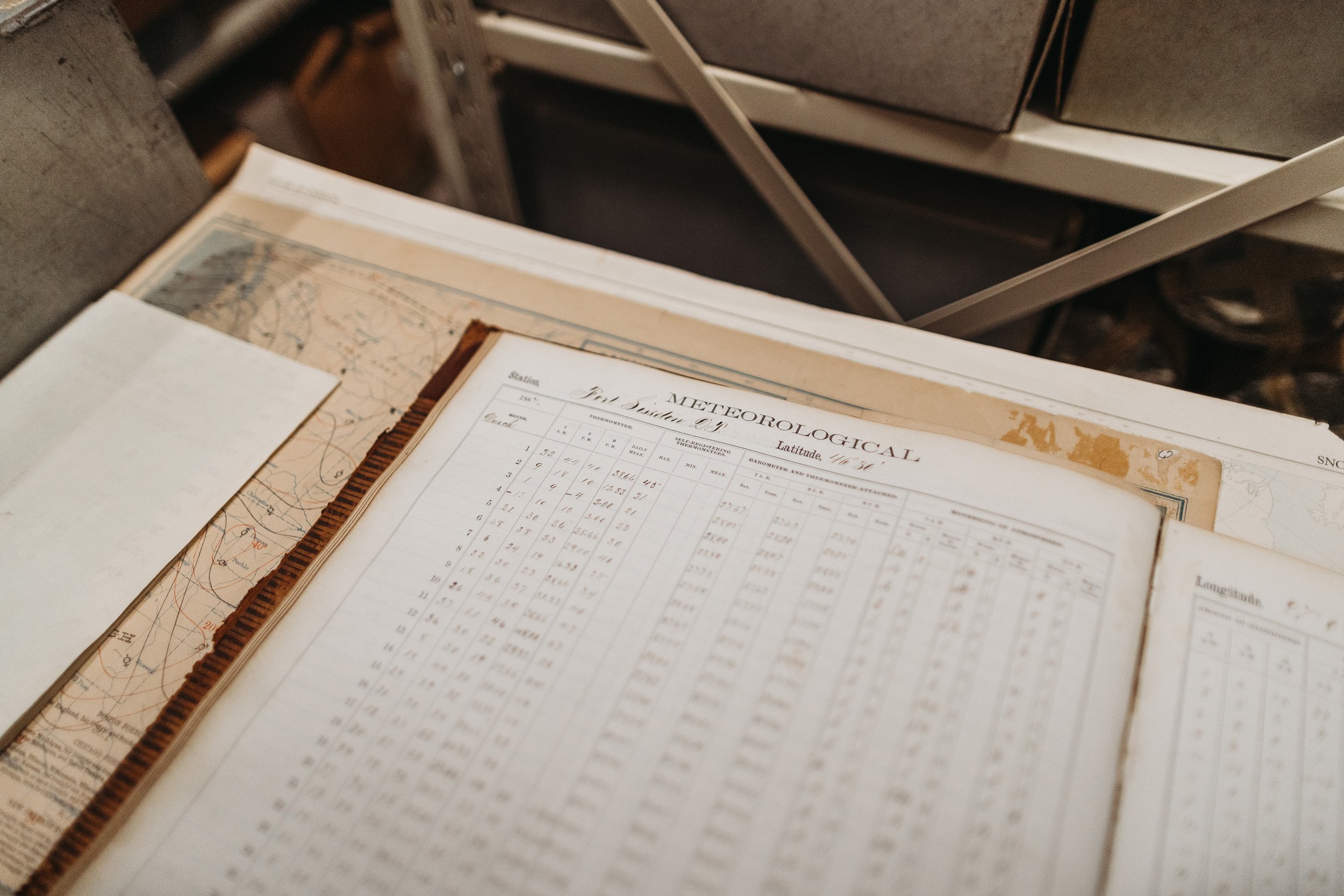

Another kind of preservation is underway in downtown Asheville, and has been since the mid-20th century, but you really have to look to see it. In 1951, the national weather records were consolidated in Asheville under the auspices of the United States Weather Bureau, making Asheville the national weather records center. Worldwide weather reports and climate data going back centuries are now housed downtown at the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) in the basement of the rather nondescript federal building on Patton Avenue. These records are the driving force behind what has made Asheville one of only a handful of major international centers for climate study. But housing and preserving information is only half the challenge; someone has to make sense of it and discern the stories the data’s telling.

matthew menne, a physical scientist with the national oceanic and atmospheric administration (noaa) and ncei.

“Our niche is understanding observational data,” says Matthew Menne, a physical scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and NCEI. He’s one of those world-renowned climate scientists you might find sitting beside you at the brewery, perhaps over a Green Man Ale at Jack of the Wood, just a few doors down from his office. Menne arrived in Asheville in 1998, and since then he’s been gathering and reading global data sets in order to build a global land database, which requires everything from international partnerships with organizations like the European Union to more intimate relationships with family-owned farms.

“There’s been a slow evolution to start to collate information into a more systematic program for monitoring the global climate,” Menne says, citing the ways in which El Niño brought the importance of global study to the fore in 1997 and 1998. But climate data was being gathered and preserved for centuries before that, with institutions and individuals responsible for curating the records.

Menne with Justin Cooper (right), an archivist specializing in the acquisition, preservation, and management of data at NCEI, in the basement of a federal building on Patton Avenue, where centuries’ of worldwide weather reports and climate data are stored.

According to Menne, institution-based weather observation in America was undertaken by the Army Signal Corps as early as 1814. “These were at U.S. forts,” he says. “They wanted someone who was educated to take the observation, and that was usually the surgeon on site.” Not long after, the Smithsonian Institution developed a network of citizen scientists that continues today as the National Weather Service Cooperative Observer Program. “These citizens are all over the country,” Menne says. “Sometimes it’s multigenerational; we have a bunch who have been taking observations for over 100 years.”

So what does Menne do with centuries’ worth of data? In the big picture, he works to combine his land observations with marine surface observations to arrive at an assessment of the global surface temperature, the hallmark metric used to quantify how much observed climate change has occurred over time. The primary goal of the 2015 Paris Accords is to limit global warming relative to preindustrial levels to 1.5 degrees Celsius. The work Menne and his team do is part of the calculations tracking the fluctuation in global temperature over time to achieve that goal. “This is how we know where we are on that target,” he says.

Among novelists, there is an old maxim that instructs writers to make the local feel universal, and while I’m hesitant to bring fiction writing into a discussion of climate science, it cannot be denied that the work happening in Asheville at NOAA and NCEI has global implications. But on a smaller scale, the amassed data has very local implications. It’s not uncommon for lawyers, insurance companies, and law enforcement agencies to contact NCEI to get historical weather information that might explain contributing factors in accidents or illuminate the decomposition timelines of human remains in investigations. “In a legal context, you get an official stamp on the record that makes the report admissible in court,” Menne says.

I tell Menne that, as someone who has lived and worked in Asheville off and on since the mid-1990s, I am shocked and a little embarrassed to only now be learning that such important universal (and local) climate work has occurred here for so long. A wry smile passes over Menne’s face. “Well, it’s my impression that our presence is still underreported and underappreciated.”

In 1951, the national weather records were consolidated in Asheville under the auspices of the United States Weather Bureau. Institution-based weather observation in America dates back to records from the Army Signal Corps as early as 1814, according to Menne.

Karin Rogers is certainly someone who appreciates the presence of NCEI and the many other public and private bodies that collect and study climate data in Asheville. A scientist whose background is in fluvial geomorphology, the study of rivers and landscapes, Rogers is the interim director of the National Environmental Modeling Analysis Center (NEMAC) at the University of North Carolina-Asheville. NEMAC is an applied research center that uses data to help people understand how to make better, more sustainable decisions. When hired by a private or public entity, NEMAC reads climate data related to a particular challenge, communicates the findings to the client, and then works to create a resilience plan to confront the issues they’ve discovered. NEMAC has another office in downtown Asheville at The Collider, a co-working space where public science collides with private capital to forge new partnerships that address climate change.

Karin rogers, the interim director for the national environmental modeling analysis center (nemac).

I meet Rogers on campus at UNC-Asheville, where I happen to serve as Alumni Writer-in-Residence, on a warm afternoon in late April. It poured buckets of rain earlier in the morning, but spring is very much alive in the blooms on the maples and dogwoods. We sit down for coffee in the student center, and I ask Rogers how she found herself as the interim head of an organization like NEMAC. She laughs. “I went to college thinking I wasn’t into science at all,” she says, and then she took a geology class to fulfill the science requirement, and she loved it. “Geology is about piecing together the Earth’s puzzles.”

Puzzling out problems is much of the work that NEMAC does. Rogers cites the “Steps to Resilience,” a five-step climate-risk planning process that helps communities understand their vulnerability to climate change. NEMAC co-developed this process with NOAA, and it is now a feature of the U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit.

The center’s first client was the city of Asheville; the comprehensive plan that resulted addressed everything from hazards like wildfires, floods, rock slides, and droughts to the Climate Justice Initiative, which collaborates with leaders in the BIPOC community to address the disparate ways climate change affects various populations. NEMAC later worked on a similar project called the Triangle Regional Resilience Partnership, which studied climate resiliency in Cary, Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill, as well as in West Palm Beach, Florida, where NEMAC discovered that the most immediate threat faced by oceanside communities was not sea level rise but inland flooding due to inadequate stormwater systems.

From left: Lindsey Nystrom, former NEMAC intern, current Resilience Associate at Fernleaf; Dave Michaelson, NEMAC software designer; Karin Rogers, NEMAC interim director; Greg Dobson, Director of Geospatial Technologies; Jeff Bliss, NEMAC principal software developer

Another recent project that Rogers mentions is the center’s Landslide Hazard Tools, which was developed in partnership with the North Carolina Geologic Survey. The tools let users learn about landslides through visuals; employ an online map to track landslides in western North Carolina; and explore the history of landslides, earthquakes, and floods in the region. According to Rogers, the tools are useful to the public, especially when individuals and organizations are deciding “where to buy, where to build, and what to insure.”

But perhaps what Rogers is most proud of is the fact that NEMAC has employed 170 paid interns since its founding in 2003, all undergraduate students from across 17 different science and humanities majors at UNC-Asheville. Rogers argues that the internship offers a truly interdisciplinary experience for students in that it requires them to read data, cull information, create models, assess challenges, and construct narratives in order to communicate their findings.

While local forager Justin Holt was a student at UNC-Asheville, he didn’t work as an intern at NEMAC. But after graduating in 2008, his humanities-based education, much of which had focused on climate change, left him with the certainty that he wanted to do something about the climate scenario that “felt relevant and was also in grasp.”

“I’d engaged in clicktivism,” Holt says, referring to the cycle of reading headlines and social media posts about climate change — an activity that can seem more effective at finding solutions than it actually is. Holt did not find online engagement “powerful [enough] when you think about the pathways for responding to these climate situations that we’re facing together.” After steeping himself in the local permaculture community, Holt began gardening but says he “spent a lot of time weeding my garden instead of harvesting vegetables.”

Justin Holt, a 2008 graduate of UNC-Asheville, knew he wanted to do something about the climate scenario that “felt relevant and was also in grasp.” He began gardening and learning about permaculture before becoming a guide for Asheville-based foraging company No Taste Like Home.

The more Holt learned about the integrative and holistic ethos of permaculture, the more he discovered that the plants he was spending all his time weeding out of his garden were not only edible but were often more nutritious than the plants he was trying to grow in the first place.

“Take the lowly violet plant, for instance,” he says. The flowers of violets, which can be used to garnish salads and thicken soups, are high in vitamin A and have properties that fight pain associated with cancer. “It’s also loaded with vitamin C,” Holt adds, “and we don’t need to do anything to grow it.”

Holt eventually began leading tours for No Taste Like Home, a 27-year-old foraging education company based in Asheville. On a warm Monday morning in early May, a tour group of locals and visitors gathers in a gravel parking area on the grounds of Christmount, a conference center in Black Mountain, about 20 minutes east of downtown Asheville. A colleague of Holt’s named June Mader pours freshly brewed tea made from locally foraged birch bark, and members of the tour group sip the hot, minty-flavored tea and get to know one another. Once everyone arrives, Holt tells the group that the bounty found on each tour is dependent on several factors, one being the location of the day’s tour; the company makes use of several local sites with a diversity of habitats where they have permission to lead tours. “It’s also different from week to week and vastly different from season to season,” he says. He then sets out leading the group toward the woods, encouraging them to engage with plants they had perhaps long overlooked.

Holt leads a foraging tour where participants can look for, locate, and pluck things to eat.

Holt pauses at the edge of the forest, where, for the next couple of hours and with his guidance, tour members look for, locate, and pluck things to eat, any early hesitancy giving way to pure delight. There’s the heart-shaped basswood leaf, which is heartier and tastier than lettuce. There’s the Japanese knotweed shoot, which tastes like rhubarb. There’s even the much-maligned pine pollen, which, to the surprise of allergy sufferers, is a multivitamin high in B, E, protein, and all kinds of minerals.

It’s all here in the Asheville area, whether you see it or not: arctic plants that have thrived since the last ice age; scientists who are tracking the changes in our global climate; solutions to the environmental challenges that face our communities. All we have to do is look. What we find will surprise us — one basswood leaf, one imaging map, one acronym at a time.

Header image: From a perch in the Appalachian Ranger District in Pisgah National Forest, writer and preservationist Jay Leutze surveys a patchwork of public and private lands.

Wiley Cash is a New York Times bestselling novelist and founder of This Is Working, an online creative community. He serves as the Alumni Author-in-Residence at the University of North Carolina-Asheville and lives in North Carolina with his wife, photographer Mallory Cash, and their two daughters.

Mallory Cash is an editorial and portrait photographer based in North Carolina. Her work has appeared in the Knoxville Museum of Art and numerous publications, including The New York Times, The Bitter Southerner, and Oxford American.