The 2019 book, Walks to the Paradise Garden follows the paths of photographers Roger Manley and Guy Mendes, and poet Jonathan Williams as they crisscrossed the South — forming friendships and becoming transformed by many the of region’s most misunderstood and beloved artists. Their work became an art exhibit at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta last year and is currently on display at the KMAC in Louisville, Kentucky. As Laura Relyea traced their steps, she came to realize that they encountered something we all might need a little more of these days: “Paradise is right in front of you. It’s not some evasive, ethereal thing that you can never grasp. It is whatever you make, wherever you make it, with whatever you have on-hand.”

Story by Laura Relyea

Photography by Roger Manley & Guy Mendes, Courtesy of Institute 193

Many years ago, a rag-tag trio of adventurers — photographers Roger Manley and Guy Mendes, and poet Jonathan Williams — hit the back roads of the southeastern United States in search of artfully human-made paradises. Their search took them to over 74 places and face-to-face with over 100 artists in 20 years. They wrote a book about it, Walks to the Paradise Garden. The manuscript gathered dust in Mendes’ photography darkroom in Kentucky until it went to print and manifested in Way Out There an exhibition last year at the High Museum. (Now, at the KMAC in Louisville, Kentucky, as Where Paradise Lay, through November 8.)

“For me, this individual project represents a collision of Southern avante-garde that’s hard to pinpoint,” said Katherine Jentleson, the Merrie and Dan Boone Curator of Folk and Self-Taught Art at The High.

“They were trying to celebrate these artists in these regions. They were going to go see these artists as a way of honoring, a chance to express their gratitude and admiration. It’s a celebration of the region,” added co-curator of Way Out There, Gregory Harris, the associate curator of photography.

My family and I had recently returned to the South, our home, after leaving for a year to try and make a go of it in Vermont. We struggled to find ourselves, or our place, after being out of context for so long. Inspired by Manley, Mendes, and Williams’ venture, and knowing I’d write about the exhibition, my husband, our 4-month-old, and I took to the backroads ourselves, in search of what remained of these artists and their work.

We found some new works, new artists, on our own. We also witnessed just how much had been lost or erased in the passage of time. Entire environments and homes of the artists they journeyed to were gone, without a trace.

“Many of the people in this book are directly involved with making paradise for themselves in the front yard, the back garden, the parlor, the sun porch, the basement. Making things for them has been a way to salvage a little dignity from often poor and difficult lives. Salvation can come, on one level, from being paid attention to and being recognized,” Williams wrote in the book. Since many of these artists were deemed local eccentrics or not noticed at all, many of them are gone already, along with their work.

Of course, there are exceptions, the Reverend Howard Finster and St. EOM’s Pasaquan among them. Jolly Joshua Samuel’s Can City was lost to us in the 1990s before this manuscript was even finished. But this “wonderbook” gives us a gift: a chance to get to know these artists and their work.

1. Howard Finster’s Paradise Garden (Summerville, Georgia), 1987-88. 2. Jolly Joshua Samuel’s Can City (Walterboro, South Carolina), 1981. 3. James Harold Jennings (Pinnacle, North Carolina), 1984. 4. Vollis Simpson Whirligigs (Lucama, North Carolina), 1988. Photos by Roger Manley.

Over the years the art world has struggled to put its finger on these artists, how to define them and their work. In the largely academic and starched high-art community, the talents and prolific outputs of such phenomenal artists as Ronald Lockett, Thornton Dial, Annie Hooper, Sister Gertrude Morgan, Howard Finster, Mose Tolliver, Eddie Owens Martin, and Minnie Black, amongst others, can be hard to pinpoint. Especially when the spectrum of their art, backgrounds, and mediums is so broad. They’ve been called “visionary folk artists,” “outsider artists,” “folk artists,” and “self-taught artists,” amongst other things, none of the titles quite hitting the mark or applying to everybody.

That’s because none of that mattered much to the artists making the artwork in the first place.

The fruits of their loving labor bring into light some simple facts that seem important for us to remember in these hard times when so many of us are looking for creative outlets to keep us from going insane. And that fact is this:

Paradise is right in front of you. It’s not some evasive, ethereal thing that you can never grasp. It is whatever you make, wherever you make it, with whatever you have on-hand. The importance is your perspective — to greet your creation with joy and to thank God for it.

For some, like Clyde Jones of Bynum, North Carolina, paradise is a passel of kids having a wild rumpus on a critter carved out of a tree that fell. For Mirell Lainhart, it was a house devoted to Christ and covered in polka dots. For the Reverend Finster, it was a ramshackle kingdom of cement, glass, and clay covered in sermons intended to beckon passersby to stop and talk awhile, maybe share a Twinkie or some beanie weenies.

For Williams, Manley, and Mendes, paradise was a camera bag, the winding backroads of the Southeast, and the good conversations that found them.

The truth of the matter was that this assignment long predated the opening of Way Out There at The High and the release of Walks to the Paradise Garden. It started in Lexington, Kentucky, in January 2016 when I met Louis Zoellar Bickett II, a self-taught artist who had recently been diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease.

It was on that assignment that my path first crossed with Guy Mendes.

Mendes has a beautiful mind that wanders, so his stories take you to all sorts of interesting places. He’ll be giving you a tour of his office and dark room and suddenly feel compelled to read you a poem. Then, a few minutes later you might be enjoying Kentucky afternoon sunlight and light conversation while rubbing the belly of his corgi in the backyard.

Fittingly, his office is a place where the imagination can soar. There are nooks and crannies filled with plants, books, and ephemera from his escapades, including those documented in Walks to the Paradise Garden, which he lobbied to name Way Out People Way Out There.

As I am sentimental about Bickett, who passed away in 2017, I’m sentimental about Mendes, too. Not only was I predisposed to be a fan of Mendes from our mutual affection of our friend, but we both had this funny habit of driving really, really long distances to hear about the lives and works of oddball artists!

Since you won’t find Bickett in Walks to the Paradise Garden, I’ll tell you a bit about him now. Like many of the artists in Walks to the Paradise Garden, Bickett’s life's work was his art. His house that he shared with his husband, Aaron Skolnick, was a living, breathing art project: THE ARCHIVE. For 30 years, Bickett tagged, described, and catalogued the sweepings of his life in a 650-page master index. He had over 500 two-and-a-half-inch binders of bills, receipts, letters, postcards, notes, gallery cards, found objects, portraits of Queen Elizabeth II, comic strips from The Lexington Herald Leader, obituaries, plane tickets, and take-out menus, amongst other things, each tagged and stamped before being described and accounted for in the master index. All this ephemera was transformed from things most of us would leave in our wallets for years into contemporary art.

Bickett said something in our interviews for that story that kind of stuck to my ribs about why he felt compelled to make his art that seems worthwhile to interject here. “It is just saying, like at [the Battle of] Thermopylae, ‘I am here,’” he told me. “You know? I was here. I was a witness.”

Back Gate, ST EOM’s Land of Pasaquan (near Buena Vista, Georgia), 1984. Photo by Guy Mendes.

Looking at Mendes’ photographs, I can hear Bickett loud and clear. That ephemera in Mendes’ office, the wood carving of a fox, the letter at his desk from Sister Gertrude Morgan, the poems and notes jotted down in old notebooks, all of his photographs and negatives – they’re a testament to those people who have affected him.

Mendes’ photographs have appeared in everything from Playboy, to The New York Times, to Garden & Gun, and back again. His photographs are in the holdings and collections of more galleries and arts institutions than you could shake a stick at. Shoot, Willie Nelson owns one of his prints.

But Mendes, of course, doesn’t really talk about any of that. He’d rather talk to you about other artists and poets he’s met who inspired him, or why the gallery down the road from his home is so important. He can recall with vivid detail the names, dates, and places of where he’s been; innumerable forests he’s hiked; interesting people he’s met. The fact of the matter is, he’s had a lifelong fascination with all the way out people way out there that he’s come across in his life.

His first step into self-made paradise led him to the Lower 9th Ward of New Orleans in the '60s and through the tall grasses of the Everlasting Gospel Revelation Room of the Mother of All God’s Children.

God gave Sister Gertrude Morgan plenty of power, and that power was Love. A whole world of Love.

That love had a ready, warm embrace around the entire Southeast during her lifetime, and when her path first crossed with Mendes, it was centered in the Lower 9th Ward.

Water can wash away a lot of things — sometimes something as awful as our sins, sometimes things as beautiful and cherished as our homes. But as Sister Gertrude I’m sure would attest, nothing can wash away God’s love of his children. Sister Gertrude made the move to New Orleans in 1939 after preaching in the streets of Columbus, Georgia, and Montgomery, Alabama. There, she established a mission, an orphanage, a chapel, and a childcare center. It was all swept away to heaven by Hurricane Betsy in 1965, which is how she came to rent a house from her old family friend, gallerist Larry Borenstein.

It was in that era that Mendes first heard inklings of her. Back then, he was spending a lot of time in Preservation Hall on St. Peter Street, also owned by Borenstein. Jazz filled the air and all kinds of artworks hung on the walls. Mendes had befriended musician Allan Jaffe and Borenstein, who would keep him abreast of interesting happenings in the art world around the city while he was away at college in Lexington. “I grew up in a segregated New Orleans, and I heard Black music at a white teenage club where Black musicians came and played. It was still heavily segregated. I was interested in learning about jazz and art and artists.”

Mendes was rightfully captivated by Sister Gertrude’s colorful artworks, which prophesied about the coming of new Jerusalem. She depicted streets paved with gold and tall modern apartments filled with happy people, including Sister Gertrude herself and Jesus.

Sister Gertrude Morgan in her Everlasting Gospel Revelation Mission (New Orleans, Louisiana), 1974. Photo by Guy Mendes.

Artist Bruce Brice took Mendes to the Lower 9th Ward, where he had a religious experience. One Mendes still seems surprised by, but had every reason to expect.

“When we walked in she hollered something from the back and said to have a seat.” The front room was her Everlasting Gospel Revelation room. “We sat down. In the far back of the shop, we could hear her singing a song that only had one word: Power. And she inflected it this way and that way, sang it loud and hard and then soft and slow while she was getting ready to come up and preach to us. Then she came up the hallway, dressed all in white at her white desk in her white room with some beautiful paintings on the wall, one of her and Jesus on a swing beside a building of New Jerusalem. On the desk was a homemade cardboard megaphone that she’d painted.

I was sitting right across the desk, and she was singing through the megaphone at me 3 feet away. It was powerful. She told me and Bruce that we were some of God’s jewelry. She told me when I was interviewing her that at some point when she was young she learned she was infertile, so instead of being a mother on her own she chose to be a mother to ‘all the children of the world.’”

After that first encounter, Mendes went back and visited with her a few times, making sure to always go visit her booth at Jazz Fest. At Christmas he would send her money for the mission. One year, she sent him a letter in return. “It kind of magically fell out of the mailbox, it made a loop-di-loop before it landed at my feet, and there it was: ‘Jesus is my airplane.’” The drawing has been at his desk every day since. He can still hear her voice chanting.

“Ooh, he’s the head boss. He’s everywhere, he’s everything. He’s the one from wherever he got the sun from he got it! He’s got great power. Waking up power. Shaking up power. Amen! Stirring up power. Oh, he’s such a wonderful counselor and he comes in so many blessed ways. He’s a doctor! He’s a lawyer! Amen. He’s a husband! He’s a wife! Amen! You know Ezekiel saw him as a great big wheel ... Jesus is my airplane and he takes me so high!”

Sister Gertrude joined the angels and her husband, God our God, in 1980. Much of her home and community in the Lower 9th Ward was washed away in 2005 by Hurricane Katrina.

Sister Gertrude Morgan, Jesus is My Airplane, 1974. Tempera and ballpoint pen on paperboard, 3.5 x 9 inches. Private collection.

Though Jonathan Williams passed away in the early 2000s, he is very, very alive and well in the pages of Walks to the Paradise Garden.

As the architect and initiator of the rag-tag crew’s undertaking, Williams had a very clear intention for what Walks to the Paradise Garden was and was not. Let’s start with what it was not: “Walks to the Paradise Garden is not an attempt to survey everything and everybody between Virginia and Louisiana, from the Ohio River to the Everglades.” It is also not “Kunsthistorisch werk or criticism, or sociology, or anthropology, or camp for the coffee table.”

It is, “A true Wonder Book, a guide for a certain kind of imagination that crops up in every generation of unabashed boys and girls.” It is also “a collection of outlandish findings by three Southern persons, all white and all male.”

Remember now folks, this was written in the 1980s and 1990s — so it is notable that, as a man of privilege, he was able to recognize it. Williams considered himself “a survivor from the Days of Highbrow Culture,” a poor man with rich tastes and a love of the lowbrow. He was also an out and about gay man in the height of the AIDS crisis, traveling through states that, at the time, openly considered his lifestyle as not only an abomination, but illegal.

On my final of seven or eight interviews with photographer Roger Manley, I was surprised to find that if Williams had still been living, we would have been neighbors. His former home with his partner Thomas Meyer, on the border of North Carolina and Georgia, “amid the rhododendron and heather and sand myrtle” was a mere 14 miles from my own, in the midst of the same such flora. And while 14 miles may seem like a heck of a long way for those living in the polis, for us still singing John Denver tunes out of our windows on switchback roads, that’s pretty damn close.

So who was Jonathan Williams, my neighbor?

Jonathan Williams and Okra the VW (Highlands, North Carolina), 1986. Photo by Guy Mendes.

Manley told me that if anyone were to do a biopic on Williams, we’d have to revive Orson Welles for the role. He described Williams’ voice as a large, baritone sort of “joyful and alive” poetry reading voice. He always smoked cigars after dinner, enjoyed a good drink, listened to jazz and classical music, and had a peculiar habit of conducting while driving. He was incredibly knowledgeable about poetry, sports, and music and dressed like an old Englishman, hand-woven socks and all.

It was following Williams’ studies at Black Mountain College in North Carolina that he founded The Jargon Society, a small-press publishing house, in 1951. As the story goes, Williams had a visit with Henry Miller in Big Sur that June. A day later, he and artist David Ruff created the first publication of the Jargon Society, which went on to publish over 115 titles – 85 books and 30 broadsides and pamphlets.

Williams leveraged the Jargon Society, as well as his connections to affluent arts supporters, to shed light on under-appreciated talent in the fields of photography, writing, and visual art. He encouraged collaboration between artists in those arenas. Walks to the Paradise Garden was one such effort. “Jonathan would go and visit artists on his own. I would, Guy would. After a couple of years Jonathan suggested we do a book. There were no contracts. No written agreements.”

“These artists had never had anyone pay that much attention to them,” Manley told me, speaking directly of the over 100 artists highlighted in the book. “Jonathan treated them like they were the most important people on earth. He was always really there.”

In fact, Williams approached these artists with such unhampered attention that he never recorded his interviews. He never took notes. He simply recalled conversations word-for-word in the days that followed.

Artist Dilmus Hall put it best. Dilmus was an artist they visited with in Athens, Georgia, before he passed away in 1987:

You have eyes

Outside

And eyes

Inside

Your heart

Is full

Of eyes

To communicate

You put the two

together

Amen!

Maybe we can all agree that an openly gay man living in the '80s and '90s would have had good reason to be leary of a backwoods Baptist preacher, especially one living somewhere as remote as Pennville, Georgia.

Reverend Howard Finster had a way of winning people over.

“Primitive Baptist preachers usually scare me to death,” Williams said. “Yet the Reverend Finster tickles me to death.”

Maybe that’s something about Reverend Finster that we could all benefit to glean a little shine from: He loved his neighbors. All of ‘em. Just as they were. “Some of my best friends are infidels!” was a common refrain from Finster. “Whatever you are, that’s what you are. I don’t try to change people around. I don’t try to make my black cat into a white cat. I don’t try to turn my bulldog into a hound,” he’d say. That all-out unexpected acceptance was a big part of his magnetic, enigmatic draw. And why he could be found hobnobbing with everyone from Michael Stipe, David Byrne, and the mayor of Atlanta, to the decadent and depraved hustler turned cult-leader artist, Eddie Owens Martin, St. EOM himself.

“He would always point out that Jesus hung out with the prostitutes and the criminals and that sort of thing,” Manley told me. “In fact, the fact that Eddie’s homemade religion was not card-carrying Christianity didn’t really bother Howard that much.” In fact, Finster and St. EOM of the land of Pasaquan, were pretty good friends and pen pals.

Reverend Howard Finster in his Paradise Garden (Summerville, Georgia), 1987-88. Photo by Guy Mendes.

According to Tom Patterson, who has written extensively about both St. EOM and Rev. Finster, the two met in 1976 at the exhibition opening of Missing Pieces: Georgia Folk Art 1770-1976. Finster and Martin even went on a trip together when the exhibition toured to the Library of Congress. The two continued correspondence up to the time of St. EOM’s suicide in 1986. “Tom and I spent the night at Pasaquan after Eddie died. We found letters from Howard to Eddie on Eddie’s desk. Howard sounded quite friendly. I think he saw him as a fellow traveler in this kind of loner world. They were very different from everybody else. What they were doing was not what other people were doing.”

What mattered to the motor-mouthed Finster, who was always first and foremost an evangelist, was maximizing his output of the word of God. He completed nearly 60,000 works in his lifetime and considered his artwork sermons in paint. “The painting was to illustrate or accompany the writing to sort of make the stories more vivid,” Manley told me. “He was proud of the fact that people would actually pay money to buy one of his sermons and put it up on their wall where they would see it every day. He reasoned that over time, whatever the message was, it would begin to sink in just from seeing it all the time.”

ST. EOM aka Eddie Owens Martin, in the Land of Pasaquan (near Buena Vista, Georgia), 1984. Photos by Guy Mendes.

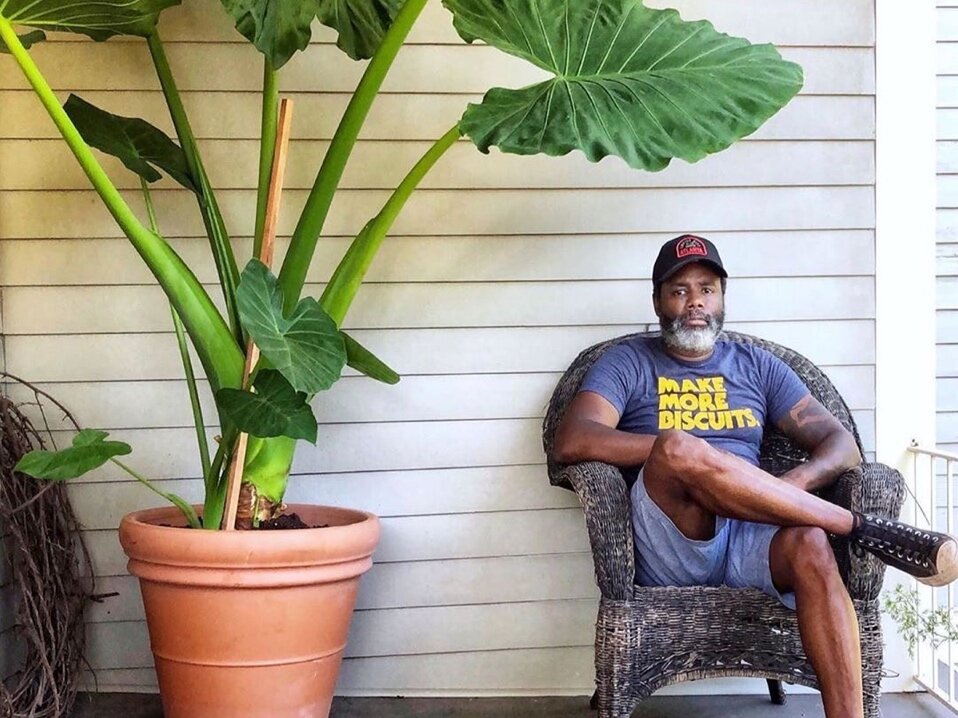

I’ve got hours and hours and hours of transcripts of my conversations with Roger Manley yet I’ve barely scratched the surface of his life experiences.

He’s a porch talk kind of guy, you know the ones where you find a good enough porch with good enough ventilation and maybe a rocking chair and some iced tea and right there, you’re well-equipped for a storied evening. I am not speaking from experience — at this point we’ve exclusively talked on the phone, but I’ve been on my porch during those conversations.

Now, when I say that I’ve barely scratched the surface of his life experiences, I am not kidding. Here’s a list of things Manley has done: he founded the triennial META Conferences at Black Mountain College in 1992 and has curated shows at over 40 institutions, including North Carolina State University’s Gregg Museum of Art & Design, where he is currently director. His documentary "MANA — Beyond Belief," premiered at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam and at the Lincoln Center in New York. Oh, and he’s received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Before all of this, he spent two years living in the Tanami Desert of the Australian Outback with the Warlpiri, Pintubi, and Gurindji people as a municipal labor supervisor.

There’s an abundant beauty to Manley’s mind. For one thing, there wasn’t a single artist we discussed in our interviews where he didn’t express something he admired. I got the feeling that he considered them all one big family. “I followed my interest. At some point I started to think about why. I realized they represented two parts of my own psychology. Outsider artists were apart from their communities, outcasts, people on the fringes. At the same time, tribal people looked completely rooted. They looked like they’d come out of the ground of where they were, they were so ingrained in their environments. The artists were people I identified with. The other had what I wanted.”

Roger Manley and Annie Hooper, circa 1983.

Manley grew up an Air Force kid — constantly moving and being stationed in new places. By the time he got to college, he had moved 29 times. This struck a chord with me personally, having been born on a military base myself and having moved quite a number of times, too. There’s something to this — being uprooted constantly at a young age, that makes a child feel both adept in the world and constantly afloat. As it turns out, the way Manley and I both adapted to our unconventional upbringings was a love of the open road that drew us to unorthodox lifestyles and by filling the roles that would usually be occupied by family or lifelong friendships with people who were willing to take us under their wing along the way, no matter how out of the way they were.

Roger Manley didn’t just meet Annie Hooper, or Clyde Jones, or Howard Finster, or Georgia Blizzard, or any of the artists that we discussed just once or twice or even a few times. They became his surrogate family. He visited with Annie Hooper at her home in Buxton, in the remote reaches of the Outer Banks of North Carolina, two to three times a year. He visited with Georgia Blizzard over 20 times from the time they met to the time she died. He discovered the work of Clyde Jones when he was getting his undergrad degree and still visits with him often, giving him a ring on the phone of the local hardware store which Jones frequents to let him know when he’ll be dropping by (Jones doesn’t have a phone, himself, you see.)

“This gave me a way of seeing art separate from the institutions and the galleries,” he told me. “It’s an approach to being alive that’s about appreciation and paying attention to the world as you pass through it. Sometimes you spend a few hours in an art museum and afterward, for a few hours, everything looks like art. You’ll see orange plastic pylons or a hole in the ground or peeling paint — it’s made more vivid. It’s made into art. We spend so much time tuning out the world. Your brain only processes a tiny percent of what you see — only one or two titles on an entire shelf of books. Visiting these artists, or any art — real art — there’s no boundary between seeing and being creative in the moment life finds you in.”

“Georgia Blizzard has lived 71 years in the mountains of Southwest Virginia on next to nothing. Raptors everywhere, and the Devil takes the hindmost.” – Jonathan Williams

The grief that strikes you from simply looking at one of Georgia Blizzard’s sculptures is crippling. Her sorrow ran deeper than a Patsy Cline song on repeat. And that’s because, according to Manley, her life was the saddest country song you’ve never heard.

Blizzard grew up an outcast in the early 1900s. She was the daughter of an Irish-American mother and an Apache father on the fringes of their Virginia community. The quiet little girl found solace making figures and pots from clay by the time she was 8 years old. She learned from watching the crawdads. Her mother taught her how to burn her creations to make them hard. She left school to serve in the National Youth Administration during the Depression, then worked in a munitions factory during World War II. She married a coal miner, but a cave-in crippled him, so she went back to work at a local textile mill. Eventually, she got brown lung and had to have a lung removed. By the time Manley and Williams came to meet her, by way of introduction from Jargon Society member Ray Cass, Blizzard was widowed and living in a tiny two-room cabin with her daughter and granddaughter.

Georgia Blizzard (Glade Spring, Virginia), 1985. Photo by Roger Manley.

“When I think of my childhood, I can get back to myself. It seems like you can create anything if you still have that childhood magic with you. You carry it down the milestones. And you think of all that’s separated you from the joy of childhood, and it seems like something evil that’s separated you from it. And yet it’s not. You had to leave it,” she told Williams.

“Georgia kept her equilibrium by making this art,” Manley told me. In the 1960s Blizzard discovered a claybank near a culvert by the cattle pond. Her own fears and worries took shape out of the clay she would carry back from the bank in plastic bags. Her first kiln was the middle of a truck tire. She set all of her fears and worries – these figurines – on fire. They would create huge clouds of thick black smoke. The whole world would smell like burning rubber for a while.

To some extent it worked — casting out her demons in the fire as she did. Manley compared his conversations with her to an encounter with the Sibyl of Cumae. Manley visited with her over 25 times before she passed away. “She really was a deep, deep person. The way she would talk about things was tremendous,” he paused a long while then, contemplating his own grief for his friend, “I loved her.”

A truck driver changed Roger Manley’s life when he was 17-years-old. He failed his first semester at Davidson College and couldn’t muster up the courage to go home over Christmas break to face his parents.

So he did what any self-respecting failing college freshman would do: He went hitchhiking as far away as he could get – to the remote stretches of North Carolina’s Outer Banks. “There was maybe one car every hour. Only one ferry a day. Terrible weather. It was raining.”

He ended up in Buxton, North Carolina, population 500. Locals at truck stops and gas stations suggested he go sea shelling. “I didn’t want to load up with shells.” Maybe he could climb Cape Hatteras? “I was afraid of heights.” Then a curious proposition came about:

“You could go see my grandmother, she makes religious sculptures.”

Annie Hooper’s grandson dropped a young Manley off outside of her very ordinary two-story home, not even bothering to go in and issue an introduction. “I knocked on the door and out came this tiny little white-haired lady with a pageboy haircut who told me to come on in.” It took Manley’s eyes a moment to adjust to the gloom of the indoors, but then he saw them — tiny faces looking at him from all over the blue shag carpet, 3 to 4 feet tall. Hooper led him down 8-inch wide pathways on a tour of the house, using a stick to flick on the light switches because she couldn’t reach over the figurines. Rotating Christmas lights illuminated some of the scenes. “Here we are with Daniel in the Lion’s Den,” she said. “He’s scared with faith in God.” Her sunroom was crowded with the children of Israel surrounding a pillar of fire.

In all, there were about 5,000 sculptures all petrified in faith, constructed of painted driftwood, putty, seashells, and cement, rooted in an uncomplicated ken of God’s love. She grew up in a big family — 14 foster children and 13 biological siblings — crabbing on the Pamlico Sound, riding horses and adventuring through the woods or down the road to the Methodist church where they gathered every Sunday. As an adult, she married a fisherman, had her son Edgar, played the organ at church, and wrote poems, which she’d have waiting for her husband every day he came home from the sea:

If I could write in the language of angels

On sheets of shining gold

And forever write my love for you

The half could not be told

Annie Hooper’s paradise was a full room — her family, her congregation, the boarders they took in during the war effort. But as life went along and those people got busy with their own lives, Hooper grew crippled by loneliness and depression that racked her from the inside out. It eventually brought on a series of blackouts and breakdowns, which led her to seek treatment seven hours away in Raleigh. There, she stayed with her twin sister Mamie, who comforted her with the same Bible tracts that she distributed to prisoners at the jail where she worked. “Annie began to sense a connection between her own pain and the biblical teachings in a direct way that she was unable to articulate verbally,” Manley says in Walks to the Paradise Garden. When she returned home to Buxton, she felt compelled to construct Moses out of a piece of driftwood and English putty. Once she started, she spent almost every spare moment making her "symbols."

“I can only live in hope, fully believing that God will bless me by making me a blessing to others, and I think I have been,” she said. “When people come, they come seeking something of the supernatural, and they get it when they get God’s word.”

Annie Hooper (Buxton, North Carolina), 1982. Photo by Roger Manley.

Hooper worked her magic in filling the room with her belief, and through that something miraculous happened: Strangers started coming by to see. Her faith acted like a homing beacon. It beckoned a curious, shy, 17-year-old Manley to her door. Manley would go on to not only visit her two to three times a year, but to tell friends, organize exhibitions, and share her work. The room started to fill not just with her statues but with kindred spirits who cared.

It’s still at work, even though Hooper is long gone. Before even speaking to Manley or Mendes about this story, I passed what seemed like an eternity staring into the hope-filled faces of her statues, a small portion of the Israelites traveling to the Promised Land. Her work speaks still. As does Sister Gertrude’s. As does the work of St. EOM, Ronald Lockett, Reverend Finster, Clyde Jones, and so many of the over hundred people that Mendes, Manley, and Williams sought over those 20 years.

It’s impossible to sum up all of the heartfelt passions of the artists in the pages or a gallery exhibit of Walks to the Paradise Garden. But when you behold their work -it will stir-up something in you and a boundary will break. It’ll beckon you into paradise — either theirs or one of your own making.

It’s up to you what you do next to go find it.

Laura Relyea is a writer living in North Carolina whose journalistic work has appeared in Oxford American, Hyperallergic, The Bitter Southerner and elsewhere. She is a former regular correspondent on WABE 90.1’s City Lights, and has been a featured guest on NPR’s On Second Thought and The Bitter Southerner Podcast.

Header photo by Roger Manley; Clyde Jones, Haw River Crossing (Bynum, North Carolina), 1988-89. Courtesy of the artist and Institute 193.