After Howard Finster died, the earth was about ready to swallow up the quirky preacher’s ephemeral garden in Summerville, Georgia. A group of preservationists got grants and funding to breathe new life into his little patch of paradise.

Story by by Anna Lockhart

Photographs by Dave Whitling

Summerville, Georgia –

Everyone around here knew Howard Finster, the local preacher-turned-artist inspired by heavenly visions that gained international fame in the folk art world. On a muggy morning at the Trade Day Flea Market off U.S. Route 27, a man selling car parts and perfume bottles says Finster used to fix his bike. John Dennis, a local attorney, remembers the Finsters had a three-legged chicken that lived in their yard. The Reverend Finster also performed the wedding rites for Dennis and his first wife in his yard. Dennis laughed, “I told him if he was such a visionary, he should have told me we were going to get a divorce.”

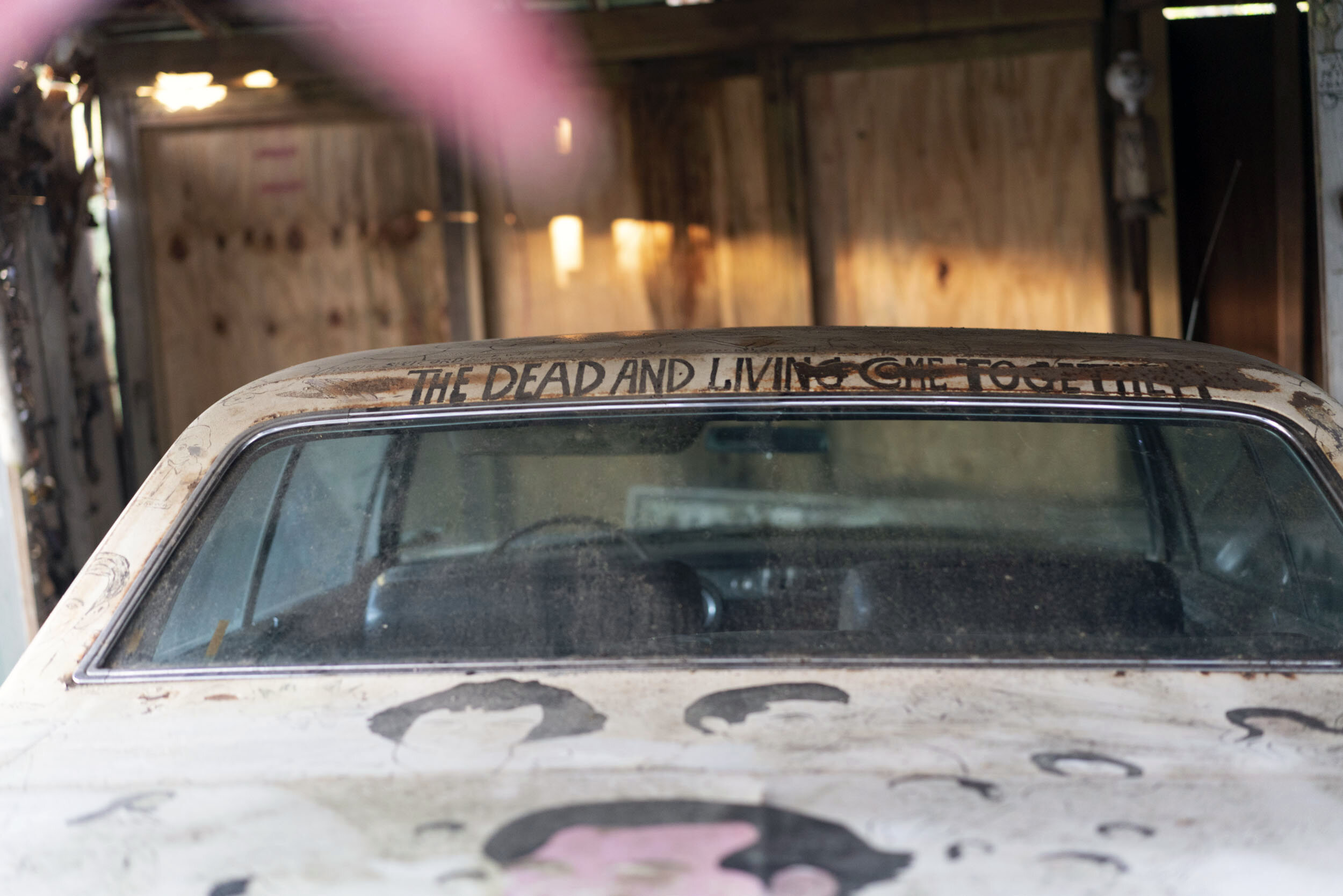

Down the street is Paradise Garden, a ramshackle compound of curated chaos filled with murals, bike parts, concrete sculptures bedazzled with found objects, and a painted Cadillac. The Mirror House shines on stilts in one corner; The World’s Folk Art Church, a tiered wooden chapel, stands above it all. Paradise Garden was once the physical manifestation of Finster’s vision. But it almost didn’t survive.

Today, Paradise Garden is poised to restore major structures on the property with a National Endowment for the Arts grant, and it boasts a trio of successful Airbnb properties. But the road to now has been rocky, a resurrection story with elements of the Southern gothic – decaying buildings, colorful characters, gossip, and ghosts from the past. At times the saga is as tangled as the brambles that choked Finster’s sculptures in the simmering Southern heat, as thick as the mud that once swallowed the mosaic sidewalks.

The World’s Folk Art Church, built to replicate the tiered mansions Finster saw in his visions, became the icon of the garden. With no blueprint or even a tape measure, Finster built it on an abandoned chapel and filled the walls of the climbing structure with art from visitors. (left) The entrance to Paradise Garden. (right)

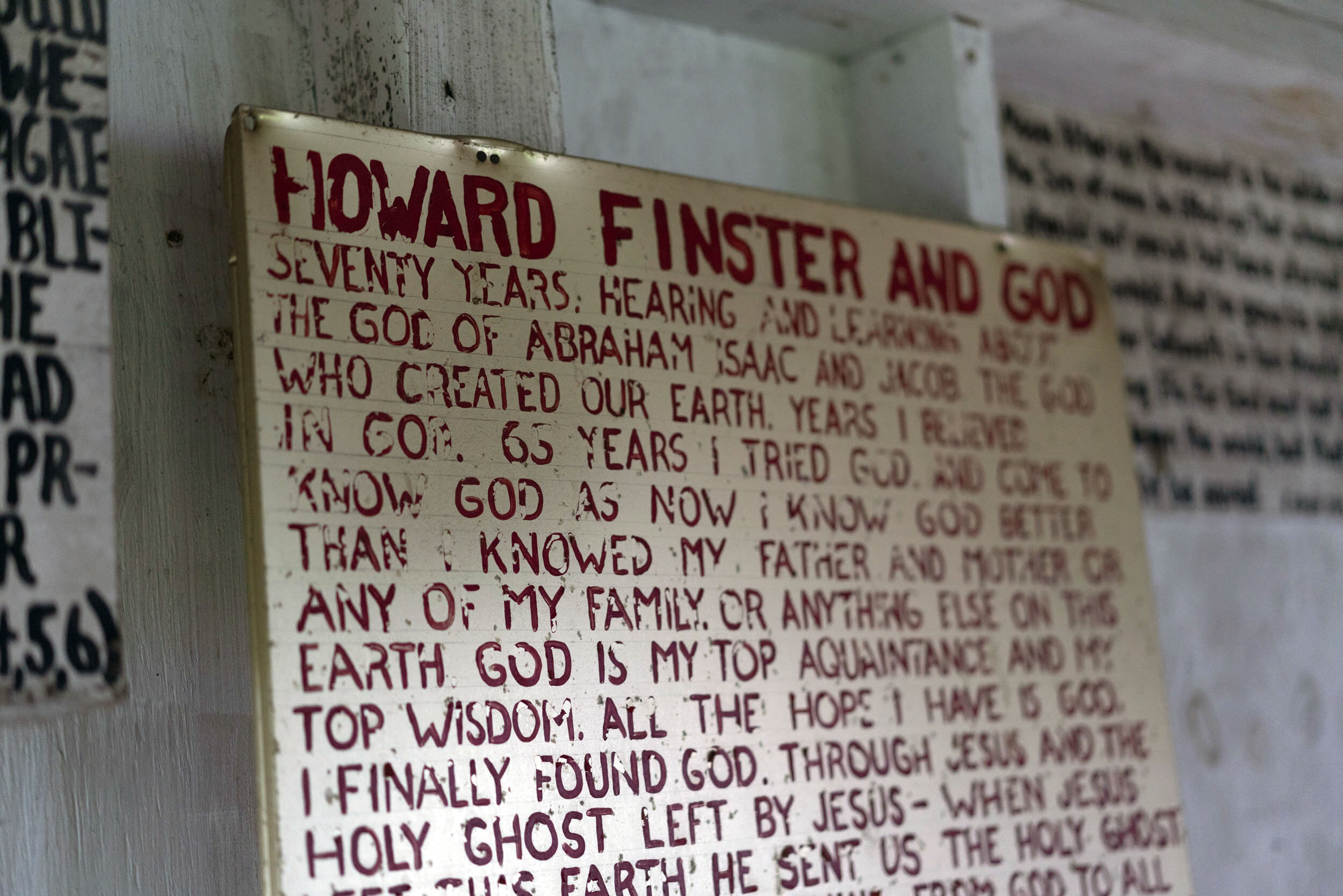

As the story goes, Finster was repairing a bike in 1976 when a dab of tractor paint formed a face on his thumb and relayed to him a message from God: “Make sacred art.” But long before the calling that jump-started his art career, Finster was creating for most of his life: performing in the pulpit and traveling throughout the South as an evangelical preacher; making pews, and clocks, and doll furniture; fixing bikes. Before he rose to fame in the 1980s — his art appearing on album covers for the Talking Heads, featured in music videos on MTV, and invited to the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian — he had a garden.

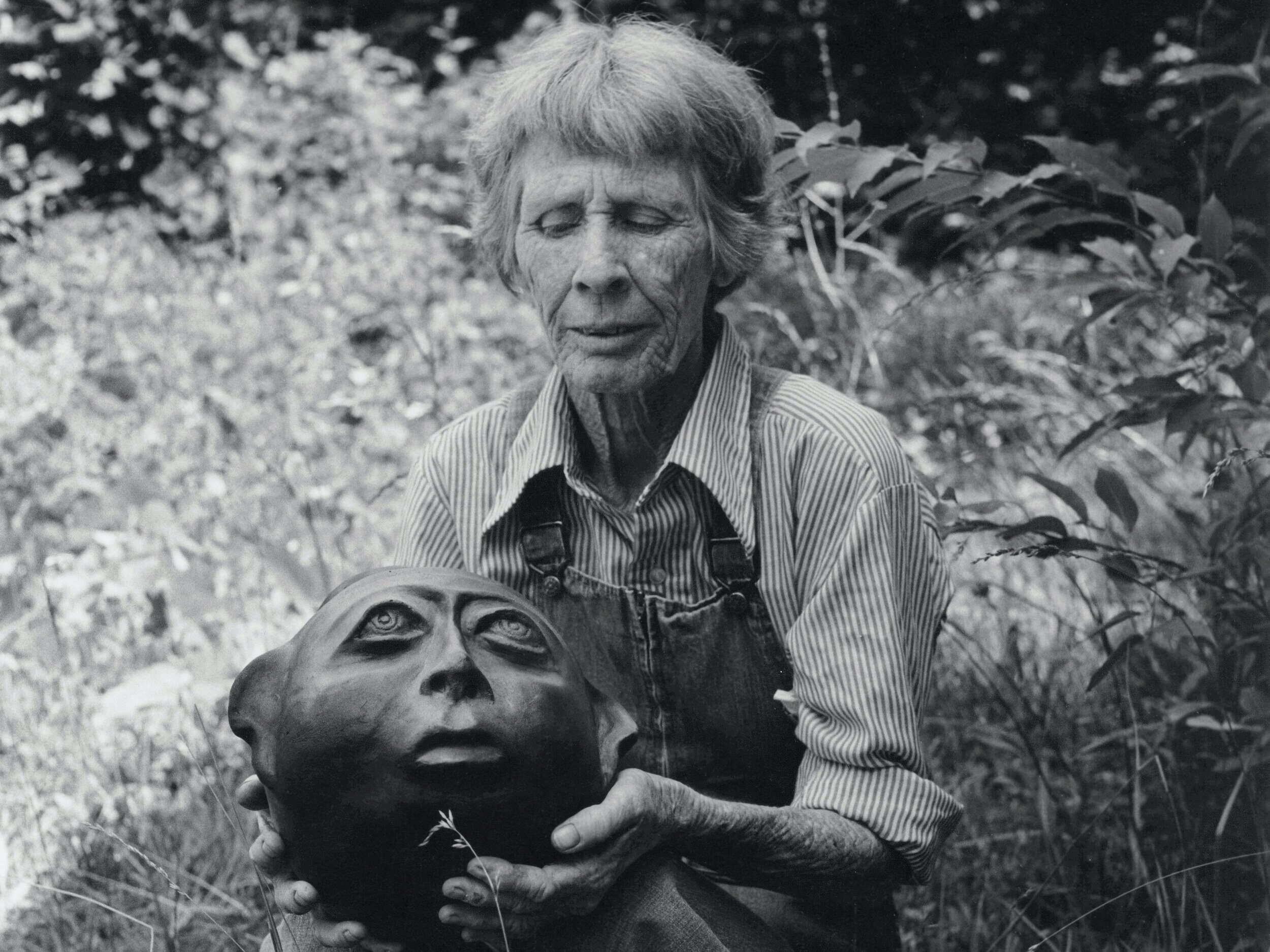

The ReverEnd Howard finstEr. Photo courtesy of Paradise Garden

In 1945, he began filling his yard in Trion, Georgia, with miniature buildings: a replica of the Baptist church, a playhouse, and a full-size dry goods store. Obsessed with the divinity of human creativity, he began collecting pieces for a makeshift exhibit on the Inventions of Mankind, everything from can openers to rubber bands. In 1960, he moved his family to a swampy property in Pennville, Georgia, just blocks from the new highway.

Finster dug dirt from the house’s basement to fill in the swamp, creating concrete canals named after books of the Bible to divert water runoff. He planted flowers and vegetables that, as the story goes, grew to twice their usual size because of the groundwater. He collected a menagerie of creatures — peacocks, chickens, goats, cats, and dogs — and added more and more pieces to the Inventions of Mankind.

He dubbed the property the Plant Farm Museum, combining his idea for a replica of Eden (“The world started with a beautiful garden, so why not let it end with a beautiful garden?”) with a roadside spectacle. Finster loved Rock City, the kitschy garden tourist attraction in nearby Chattanooga, Tennessee, and the roadside museums he’d visited with his family on vacation in Florida. He envisioned his yard to be a spectacle in miniature. Ever the showman, Finster’s performative sermonizing drew crowds, too.

People came, and word spread, first to an Atlanta news station that did a segment on him in 1975 (Finster first told them the place wasn’t finished so they couldn’t come.) Esquire published a piece that same year on the “Garden O’Paradise.” Thus, Paradise Garden was christened. In 1976, Finster was featured in his first major art show, a Georgia Council of the Arts traveling exhibit of regional folk artists. In 1982, Finster became the first self-taught artist to receive a National Endowment of the Arts grant, which he used to create the World’s Folk Art Church and to add new embellished sidewalks. The World’s Folk Art Church, built to replicate the tiered mansions he saw in his visions, became the icon of the garden. With no blueprint or even a tape measure, Finster built it on an abandoned chapel and filled the walls of the climbing structure with art from visitors. Over time, he purchased the entire block surrounding the land, including multiple buildings on four acres.

Paradise Garden, a ramshackle compound of curated chaos filled with murals, bike parts, concrete sculptures bedazzled with found objects, and a painted car.

Paradise Garden was an open air studio for Finster, where he created, displayed his work, and welcomed thousands of visitors. The “bunk house” let him take naps in the middle of the day (he wrote of keeping his shoes on for days at a time while working) and even housed the occasional young artist.

Without knowing it, Finster had created a folk art environment, a vernacular art environment, an outsider art enclave. Some call them “yard shows.” Often spiritual in nature, these do-it-yourself museums express loneliness and flamboyance; they are outside the confines of the formal art establishment of galleries and museums, but a world of their own in the creator’s own realm. Created with the author’s own materials, vulnerable to their environment, they are ephemeral by nature.

The South is populated with such places: L.V. Hull’s art yard in Kosciusko, Mississippi; Nellie Mae Rowe’s “Playhouse” in Vinings, Georgia, is now closed; Joe Minter’s African Village in Birmingham, Alabama, still stands; W.C. Rice’s Cross Garden in Prattville, Alabama, is in severe disrepair.

Most of these kinds of installations are not built to last, and many don’t. The Grassroots Art Center in Lucas, Kansas, estimates that 90% of all environments are destroyed after their owner dies. Unlike Finster, most don’t achieve fame or notoriety until after their death, if ever. In Walks to the Paradise Garden, Roger Manley, Guy Mendes, and Jonathan Williams tracked down dozens of Southeastern eccentrics who created their own homespun art shows. For them, Williams writes, “Making things … has been a way to salvage a little dignity from often poor and difficult lives. Salvation can come, on one level, from being paid attention to and recognized.”

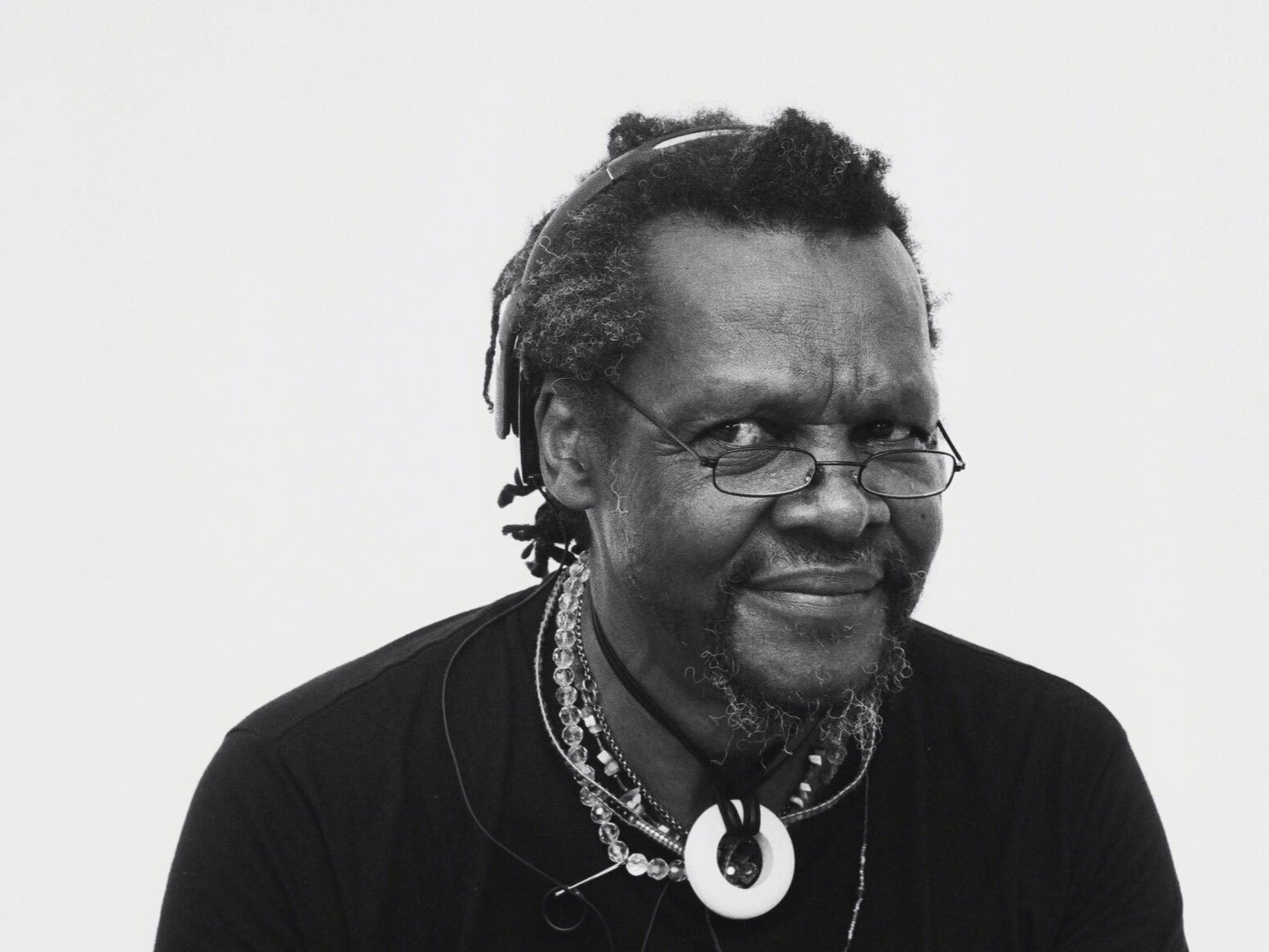

Many yard show creators are marginalized, and their home-grown art shows are a way to attract an audience without inviting too much attention, like Alabama artist Lonnie Holley, who creates meaningful assemblages of discarded objects. He might use a railroad tie and a tire to represent the weight of oppression, the toils of labor, or the cyclical nature of the universe. But the objects could also be explained away, or misinterpreted as a bunch of junk.

Along with acclaim and fame in the art world and beyond, Finster’s showmanship and his savvy marketing skills were one way he attracted visitors and eventually gained support to keep his garden. But he was also a straight, white man, points out Katie Jentleston, the Folk Art Curator for the High Museum of Art. “People who are disrespected and undervalued in their lifetime make art environments to attract people to their yards and interface with strangers, but also have a tension to push people away,” Jentleson says, pointing to Royal Robertson, a Black artist from Louisiana whose yard art is welcoming, but also includes “No trespassing” signs and spiritual admonishments.

Though Finster wasn’t always welcomed by Summerville — some recall people shooting bullets at the house — he was a prominent member of his community. He built his space to be seen. Yet even with his acclaim and fame, the property’s fate was tenuous.

Inside the Meditation Chapel at Paradise Garden

According to Lisa Stone, whose work at the University of Chicago and the Kohler Foundation focused on the preservation of art environments, the most common reasons for such places falling into disrepair are lack of funds, real estate issues, zoning issues, and lack of knowledge regarding preservation. Almost every box is checked in the saga of Paradise Garden. Chattooga County is poor – rated in Tier 4 by the Georgia Department of Community Affairs – so community monetary support was minimal.

Finster had worked for decades on his garden of Eden, in his words killing “over one hundred snakes, thousands of trees, bushes, vines and thorns,” all with hand tools. But taking care of it after he was gone proved difficult.

I visited Paradise Garden when I was a kid in the 1990s. Aside from the heat, the baubles, and the plywood angels, what I remember most is the crowd surrounding Finster sitting in his house, so thick my parents and I couldn’t make it into the building. We’d come from Chattanooga, an hour north of Summerville. A collector of castoffs herself, my mother was intrigued. Generous and charismatic, Finster had thousands of friends from all walks of life. Even chance encounters transformed people and changed the trajectory of their lives. For me, seeing the way Finster arranged garbage as if it was precious gave me a kind of hungry hope. It changed the way I saw things, and it’s why the place stuck in my mind forever after. Finster made people who felt like castoffs feel like they were precious, too. It’s a big part of why so many rallied around the property to save it. But it's also a reason for some of the conflict surrounding its preservation.

Finster died in 2001 at 84. He had slowed down his public appearances in his older years, returning to the garden only on Sundays for the visitor meet-and-greets he cherished.

“The garden kind of fell into my lap,” says Beverly Finster-Guinn, Finster’s youngest daughter. She describes how her father loved to greet people, but she could see how it wore on him. She remembers taking him to New York City to the Museum of Modern Art shortly before he died, and wonders if that trip did him in.

Finster-Guinn grew up watching her father develop as an artist, and the garden was her playground. She was much younger than her siblings — Roy, Eugene, Gladys, and Earlene — who had grown up seeing their father as a minister.

Pauline Finster, Howard Finster’s endlessly supportive wife, once said of her husband, “He was the busiest man I ever met!” (He anointed a building in the garden as Pauline’s House. She reportedly never used it.)

By the '90s, Finster was declining in health, and the garden was too. Even in 1987, Finster lamented in Howard Finster, Stranger From Another World, a book of transcribed narrative interviews, that he had been so busy with making art that he had neglected his garden. Brush had grown to the point of obscuring art pieces; the canal system clogged and killed the fish that once lived in it. “What I’m hopin’ to do is go back to work on my garden and finish it up,” he says. “I never have been able to finish it ‘cause o’ all these other things I was impressed to do.”

The fate of the artwork he’d churned out was in question too. In the early days, Finster declined to sell his art, once telling someone, “I’m not doin’ paintings to sell. I’m doin’ ‘em to go in my garden.” Later, he worked with art dealers, mass produced pieces, and sold them for a small price. Finster’s adult children were involved to varying degrees, especially Roy Finster, who even posted signs around town claiming Finster-Guinn was getting an unfair chunk of profit; Finster-Guinn maintains she made very little money. As word of Finster’s value spread, people had started helping themselves to pieces.

And then there was the High Museum deal. In 1996, art pickers took away two truckloads of art from the garden for $30,000 and sold them to the High for a higher price. Among them, important pieces like The Lion and the Lamb, and even the Bicycle Tool sidewalk he created when he put away his tools to create art. Larry Schlachter, a local gallery owner and long-time friend of Finster’s, said it felt like a death in the family when the Coin Man was sold to a private collector. Rumors had it that even the Serpent’s Mound, a concrete hill of biblical snakes that was famously featured in the R.E.M. music video for “Radio Free Europe,” was sold at one point to a private collector - though the sculpture stands in the garden today.

The transaction has become lore in the Finster universe. Roy Finster authorized it. Some say Finster signed off, others don’t. David Leonardis, a friend and devotee who owns a Howard Finster gallery neighboring the garden, says, “They took everything they could dig up with a backhoe.” Tina Cox, the current executive director of the Paradise Garden Foundation, says debunking the idea that the High took everything is a large chunk of her job. As for Finster-Guinn, she was driving to an art history class at Kennesaw State University when she saw a truck flying down the highway with her dad’s sculptures in it. She came home and put up a chain link fence around the property.

As Howard Finster’s health declined, collectors began helping themselves to his work, which was not for sale. One day his daughter, Beverly Finster-Guinn, saw a truck flying down the highway with her dad’s sculptures in it. She came home and put up a chain link fence around the property.

Talkative and as generous as her father had been, Finster-Guinn quit her job as a teacher at Summerville High School to manage her father’s art business for a time. By selling her father’s art in a more controlled system and acquiring real estate, she made money to pour into the garden, and eventually bought it and formed a nonprofit, the Paradise Gardens Park and Museum shortly after Finster’s death. The fence was meant to create a boundary for the Garden; charging admission provided revenue to keep up with landscaping and maintenance.

By the time her father died, the Gardens were in disrepair. Overwhelmed, Finster-Guinn enlisted the help of volunteers, including Tommy Littleton, a reverend from Alabama who had befriended Finster in the '90s.

“It took two weeks with a weed wacker just to get the grass under control,” Littleton recalls. “Once I was done, I had to start over again.” The structures were caving in, especially the World’s Folk Art Chapel. Weather had taken away from much of their original splendor. Water was everywhere. Over time, the intricate canals had become ineffective with age. The heat made everything grow faster and decay further, moss growing, mud swallowing. Though Finster had built it painstakingly, it was becoming clear that it would take more than a weed wacker to preserve it.

Finster-Guinn had leased the property to Leonardis, who had discovered and begun collecting Finster’s work as a teenager. Hustling art and sometimes cars, he traveled between Chicago and Summerville, eventually purchasing Finster’s first home in Pennville on a far corner of the Garden on a tax sale for $1,400. He named it the Howard Finster Vision House. For a fee, visitors can have their name written on the wall of the house. The place is in poor shape, with water damage and repairs ongoing, and open only for appointments.

“Howard Finster art will protect your house from tornadoes, fire, and theft,” he is fond of saying. “I’ve saved two souls with Finster art.”

Leonardis hoped to buy the property, but Finster-Guinn sold to Littleton instead. In an interview with the Chattanooga Times Free Press, Finster-Guinn said she would not feel at peace selling to Leonardis because he wasn’t a Christian. Leonardis fought back, convincing the paper to issue a correction to the statement: “Finster’s job is to save your soul, and my job is to sell you valuable contemporary folk art, but I am indeed a Christian.”

Through this period, Paradise Garden was mostly shuttered, open only on summer weekends, by appointment, and for the annual FinsterFest fundraiser.

“There was a time,” recalls Norman Girardot, a religious studies Professor Emeritus at Lehigh University who studied the mythology of Finster’s work, “When I thought, maybe it was meant to fall back into the swamp.”

Others from the art world suggested the same, that an outdoor art space might be meant to fade away at the will of its natural habitat.

Littleton scrambled to find funds, hosting fundraisers to fix the garden in pieces: one gala for the roof and balcony of the chapel, another to buy the original Finster house to turn into a gallery space. He even said he took $100,000 from his retirement to help with funding. But the estimates to repair the damage were upwards of $5 million. He had lobbied to find a university to take it over and had approached philanthropists and art collectors for interest, 35 in total. “But the Garden was already orphaned in people’s minds,” he said.

In 2004, Finster-Guinn lost the insurance on the property. In 2008, the New York Times visited the gardens and declared them to be in shambles. Leonardis was quoted, implying that he wanted to wrest the gardens from Littleton, who he deemed incompetent.

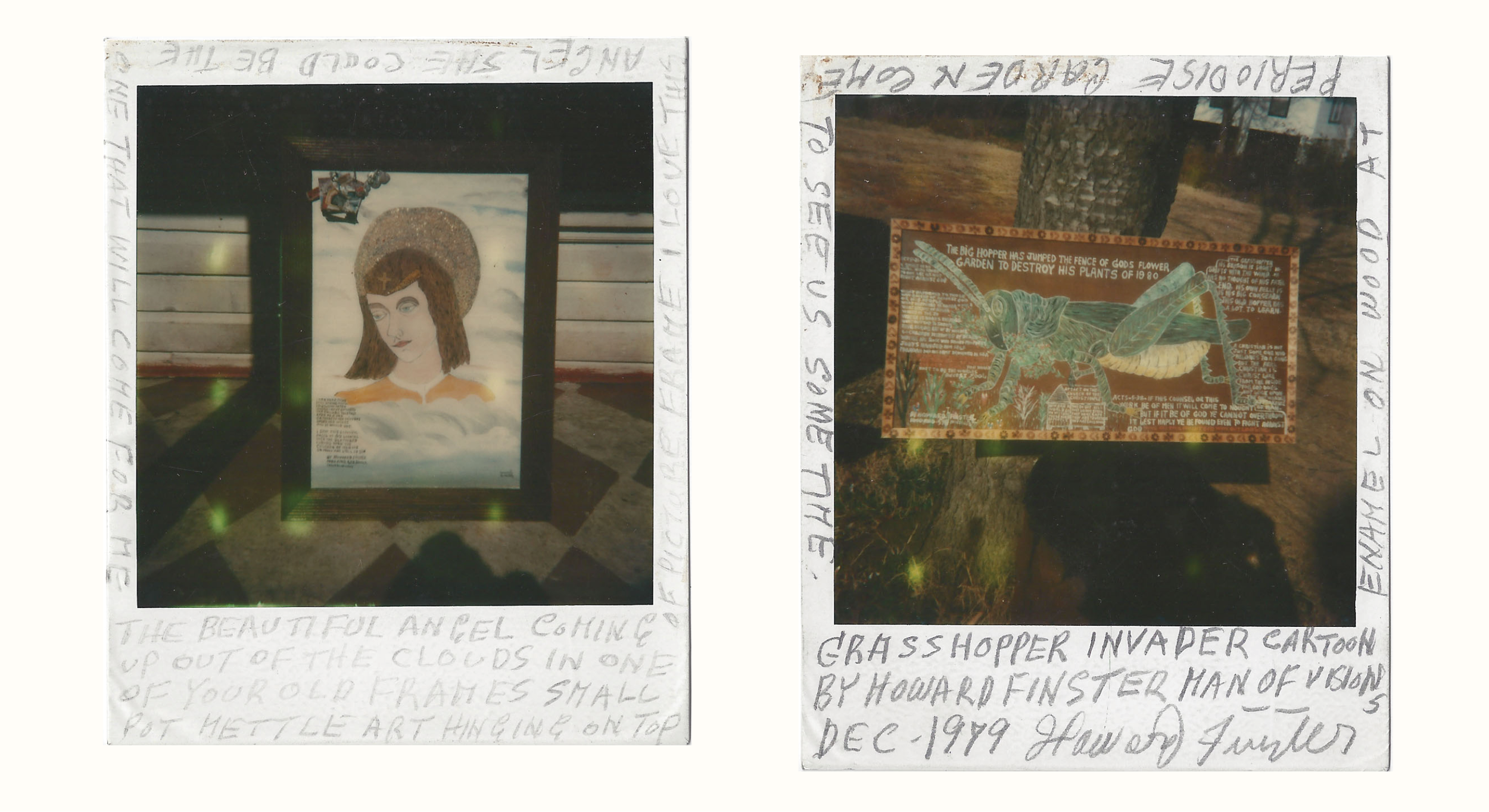

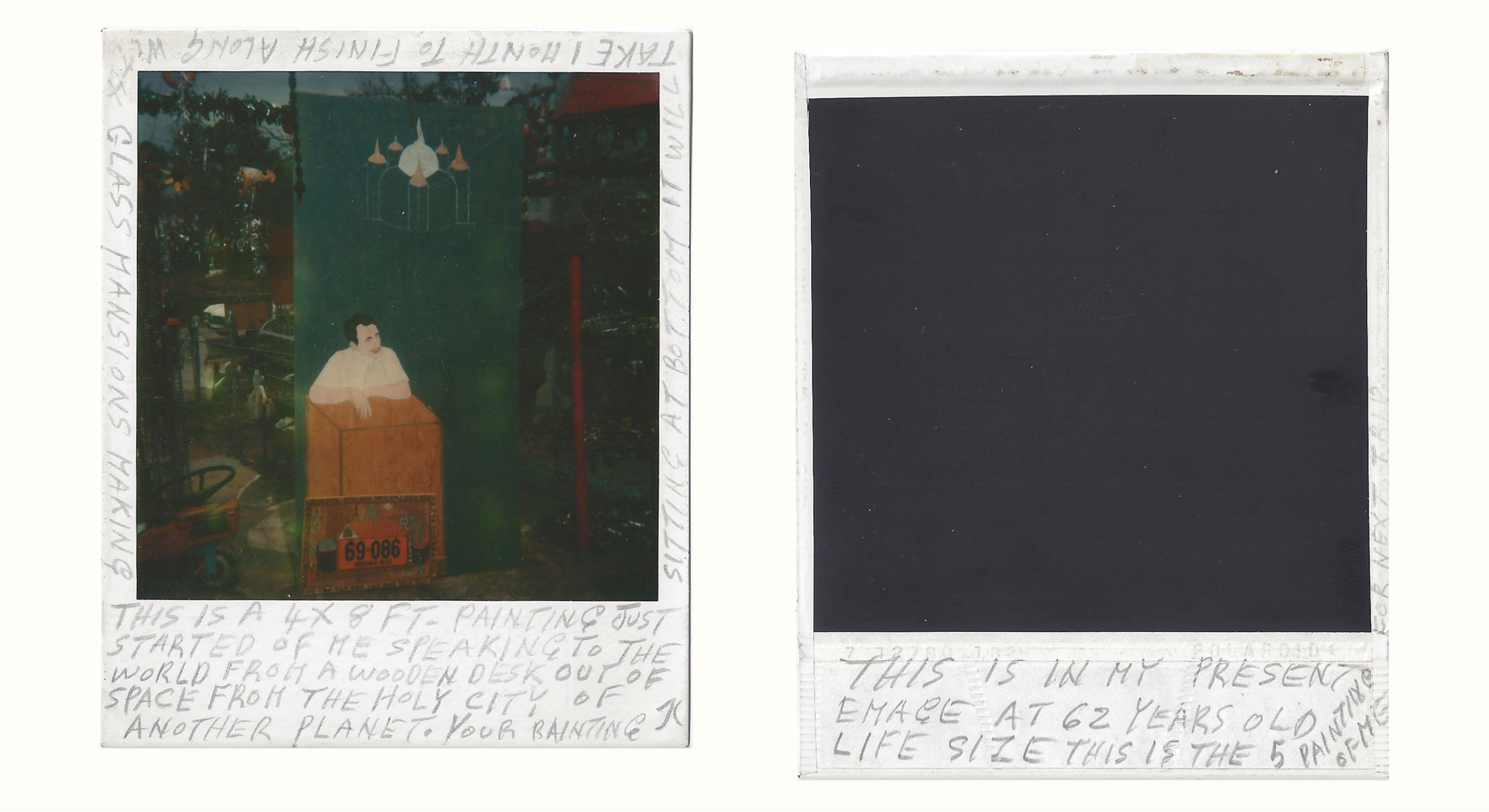

Polaroids by Howard Finster, courtesy of Institute 193

“When the recession hit, you could have rolled up the sidewalks in Summerville and called it a day,” says Jordan Poole, a Summerville native. With a freshly minted master’s in historic preservation from the Savannah College of Art and Design, he had worked at Mount Vernon and Elizabeth Furnace in Virginia. Poole is a fast-talker full of quips and one-liners. His grandparents owned a store a few blocks from the Finster homestead, and he grew up knowing the Finster family; he’d even shown art at a FinsterFest years before. But Poole had gotten out of smalltown Summerville as soon as he could. Atlanta had suited him: it was cosmopolitan, urban, diverse, and full of the art world connections he needed to build a career.

But, he was called home. Friends at the Georgia Trust (Janet Byington, congressman Phil Gingree, and newly elected County Commissioner Jason Winters) tapped him to come work on Paradise Garden.

He had a long talk with Jesus. Coming back to his hometown - “A single guy with a dog,” as he put it - wasn’t his plan. “I thought, ‘If I don’t save what’s important in my own hometown, what am I gonna do?’” he says.

Littleton had been lobbying the trust to get Paradise Garden listed on the National Historic Register, looking to join the recently added Pasaquan, the far out enclave of Eddie Own Martin, in Buena Vista, Georgia. With Poole’s experience in grant writing, the team landed Paradise Gardens on the Places in Peril list in 2010, a designation of the National Register of Historic Places to help highlight sites in need of saving. The Appalachian Regional Commission granted them $125,000, which allowed Chattooga County to purchase the property without using taxpayer dollars. Winters did not respond to requests to discuss the purchase, but in a 2012 article in the Chattanooga Times Free Press, he said he hoped to see the garden as more of a tourist attraction. Maybe it could generate revenue for Chattooga County and create jobs.

In 2012, the Howard Finster Paradise Garden Foundation was established, and the county leased the garden to the Foundation to run independently. Poole was hired as the executive director — a move that surprised and angered Littleton, who had thought the purchase would leave him in charge.

But with Poole at the helm, more grants came — a $445,000 grant from ArtPlace America (the first rural site in the grant cycle to receive it) and $225,000 from the Education Foundation of America.

“It was like winning the lottery,” says Poole. The Foundation established a phased capital campaign, and started some restorations, enlisting the help of volunteers and even inmates from a nearby state prison through a partnership with Chattooga County. The bike sheds were stabilized, a subtle reframing that left the rusty tools just as Finster had left them. The studio was rehabbed, and an extension to a house on the property was built to make a visitor’s center. Poole and his crew constructed a timber frame truss system to provide support for the upper roofline and decking of the upper cupola of the World’s Folk Art Church, and put in interior structural support. Battling mud and mosquitoes, they also restored the grounds, lowering the water table by implementing drains and gutters — an addition and improvement to Finster’s original system.

Poole used an archeological approach, uncovering mosaics from beneath a foot of mud, and documenting the state of the original art pieces around the property, all with the artist’s hand in mind.

“In restoration there are different schools of thought — one is that there is beauty in decay, the other is the idea that, ‘If they would have had it, they would have used it,’” says Poole. The latter justifies things like adding sidewalks to enhance a visitor's experience. The mosaic garden, the original entrance, was restored, and new mosaic sidewalks were discovered. A team of engineers and preservationists came to study the World’s Folk Art Church to envision its use as a multi-functional performance and event space.

Slowly, they began inviting visitors back to Paradise Garden. Kathy Berry, a local librarian, was hired as a part-time assistant, in part to sit on the porch and wave visitors in. Poole likens her to Aunt Bea, the motherly housekeeper in the Andy Griffith Show.

In 2012, the Folk Art Society met in Atlanta and honored Paradise Garden, designating it, “a folk art environmental site that should be protected and preserved.”

Littleton says the county and Poole did great things for Paradise Garden, but maintains he was deceived. Part of his anger lies in the way the garden is presented.

“You have to protect the legacy and the person, not just the buildings and the work,” he says. “They removed his identity as a pastor, they removed any language of him as a person or a preacher, and that’s not true for him as an artist.” Talk of staging “Hidden Man” by Pamela Turner, a play based on the unlikely friendship between Finster and Robert Scherer, a gay young punk in the ‘80s, horrified Littleton. He says Finster would never have approved; Finster-Guinn thought so too.

Girardot disagrees. Finster’s welcoming nature meant everyone projected upon him the message they wanted to receive.

“Everyone involved would say, “Our vision is the correct one,’” he says. “But Finster wanted a lot of things; it depended on the time you spoke with him.

Despite all the trouble, “I think my father would be happy with the way his place is being handled now,” says Finster-Guinn when I talked with her at Finster Framing, the framing and art shop she owns in downtown Summerville. In the shop, she sells prints of her father’s work, art books featuring Finster (including his illustrated version of “A Night Before Christmas”), and her granddaughter’s art work, which features similar motifs to Finster’s, including parts of the garden. Finster-Guinn paints too: lush neon pieces featuring angels, animals, and tiered churches. (Finster’s son Roy and his grandson Michael are also artists.) Finster-Guinn is in touch with the Paradise Garden Foundation, and comes to the garden for events, fundraisers, and volunteer days.

The county purchase is largely seen as its salvation, agrees Cox, who was named executive director in 2017. Cox started volunteering at the garden in the '90s, after making a New Year’s Resolution when she was 30 to learn more about art. She was a part of a group that worked with conservator Tony Rajure to restore pieces gifted to the High, and traveled from Atlanta regularly to work on the grounds. She served on the board and retired from corporate America to take the job of director. Under Cox, the foundation put together a plan to develop funds and build capital. In 2017, the foundation received its third NEA grant. With that money, Cox says the foundation hopes to hire a historic architectural firm to finally do comprehensive restorations on the Folk Art Church, as well as other work on the rest of the property. She also helped build on the Airbnb properties that help with revenue and house artists in residence. Monthly tours, classes, art camps, workshops, and concerts filled the garden, and FinsterFest saw record breaking numbers. One task on Cox’s list is to get interstate signage for Paradise Garden. Today, she is confident that Finster’s vision will continue to live on.

On a hot day in June, Cox greets visitors from the porch where Finster used to sit. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the garden is newly reopened after a six week closure — a productive time for renovations and behind-the-scenes work, Cox tells me. Guests are sparse, signs guide them to socially distance, and many wear masks. It’s a stark contrast to the crowd I remember from my last visit. Cox recalls sitting in the sweltering heat in the Bible House listening to Finster expound for hours. At the rusted story-high bike mound, she points to a wily ficus tree snarled between the bike parts. “Usually we would get rid of this, but it’s holding up this entire structure,” she says.

The Outsider Art Trail Tour is in its third year, a self-guided weekend that sends visitors to Trade Day and a hand-made rock garden in Calhoun, Georgia. The Airbnb bungalows, outfitted with Finster replicas and Pinterest-worthy furnishings, are occupied and Paradise Garden is a “Super Host.” One guest says the cement canals would make a great mini-golf course. Teen girls take selfies in the Mirror House.

Leonardis sits on the back porch of his studio house outside the fence, looking on. “I’ve never met him,” Cox remarks.

When the pandemic began shutting things down, Cox was overwhelmed. “I sat down in the garden and talked with Howard,” she says. “I asked him how we were going to get through this.”

But the garden’s closure proved productive for deep cleaning and repairs, and with folks looking for safe places to get out of their homes, the garden saw the same foot traffic as a normal year once they reopened, despite having to reschedule — then cancel — the annual fundraiser, FinsterFest.

But the real boon appeared in July, when prominent architecture firm Lord Aeck Sargent did an appraisal of the World’s Folk Art Church. With a bounty of grants and donations — including the NEA grant, but also a handful of newly announced gifts — the Foundation will give the Church a new roof, and will put into action a four-year strategic plan to totally restore the building should be put into place by May 2021.

The busy garden once thrummed with a cacophony of painted wood signs in Finster’s hand: scripture, stories, and directives, like “Get Right With God”. Many of these have lived in storage for years, but a new initiative will restore and recreate many of them to be reinstalled throughout the garden.

“We can never take it back to where it was in the '80s in its heyday,” says Cox. “But this will let people really see the thickness of the art environment — so that you’ll have to come back again and again to see it all.”

The signs will be restored as porcelain-plated enamel, the kind of bright, weather-resistant signs you might see on old gas station signage.

It was providential, Littleton says, that he ran into an old friend who told him of the developments happening at Paradise Garden. Over the past eight years, he and the members of his nonprofit had been watching the Foundation under Cox’s leadership, warily. The new developments pleased him. The World’s Folk Art Church restoration and the signage reinstallment are symbolic for Littleton, that the Reverend Finster’s spiritual mission is being honored.

“The Garden had gotten extremely sanitized under the previous leadership, and folk art isn’t like that, Howard wasn’t like that,” says Littleton. “It’s time to lay down the sword, turn the page, and continue to hope for more good things for the garden.”

So he approached the Paradise Garden Foundation to discuss selling them the house he still owns, on the corner of Knox and Rena streets, Finster’s final home before he moved across town to Summerville. It’s been mostly empty since 2012, remnants of its days as a gallery and frame shop (Finster-Guinn’s original location) remaining, the original Paradise Garden sign painted over. The Foundation wholeheartedly agreed, and they struck a deal to acquire the property. The fence between the properties will be removed, the building’s HVAC system and plumbing repaired. Finster’s well-kept ‘76 Lincoln and two hand-painted school desks unearthed from the carport will be displayed. Murals of angels painted in the style of Finster on the side of the garage will stay. Cox and Littleton both imagine the house will be used as a multi-purpose community space for educational programs. A newly-opened green space between the properties could host concerts, festivals, and events.

“This could be a vibrant art campus,” says Cox, a place to host visiting artists, international students, and scholars from all over the world. “It will be exactly what Howard envisioned.”

Leonardis was unaware of the purchase, and wishes he had been invited to make an offer himself. Still, he is glad Littleton is giving up the underused space. “I look forward to an improved Howard Finster experience,” he says.

Back in June, before the big news rolled in, the garden feels pregnant with hope. Compared to earlier photos and my own memory, the garden is more barebones. The plywood heads and angels and some sculptures are gone. The World’s Folk Art Church is closed, with a hand-written note on wood still tacked to the door:

Help save the garden chapel — thousands enjoy. It is a place of free weddings and many school groups over 40 years.

But, the original structures are still there. Artwork by visiting artists still hangs on the walls of the Rolling Chair Ramp, Finster’s scrawl beneath with names and dates. The mosaic wall, my favorite place, is as dizzying and packed as ever; Barbie dolls, tea cups, and electrical wires still hang from the entrance where kids once wheeled their broken bicycles.

A teenage girl carries away a tin lunchbox her parents bought her from the gift shop with a black and white drawing of one of Finster’s tiered church mansions, like the World’s Folk Art Church standing nearby.

“You can really feel his presence here,” she says.

Corrections, September 17, 2020, 3:45 p.m. :

Royal Robertson's name was previously mentioned as Royal Roberts.

An earlier version incorrectly attributed this quote by Jonathan Williams, “Making things … has been a way to salvage a little dignity from often poor and difficult lives. Salvation can come, on one level, from being paid attention to and recognized.”

Pauline Finster was previously mentioned as Paula.

The "Coin Man" sculpture is not in the High Museum's collection, as an earlier version of this article stated, but was bought by a private collector who still has it.

In a previous version, it was stated that the Serpent's Mound had been sold, but this has not been confirmed by the foundation.

The newly purchased former home and gallery of Howard Finster is located at the corners of Knox and Rena Streets (not Penn)

Anna Lockhart is a writer from Chattanooga, Tennessee, who now lives in New Jersey (by way of the midwest and Philadelphia). She works as an editor and freelance features writer, dabbles in scholarship focusing on children's literature, and sells vintage clothes. Her work has appeared in the Chattanooga Times Free Press, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Atlantic, and more. Follow her on Twitter @AnnaLocky.

Dave Whitling is co-founder & creative director for The Bitter Southerner.