Words by Eric NeSmith

Featuring the Photos of George Masa, Courtesy of Highlands Historical Society

October 26, 2021

It had been a bit since I’d seen any kind of marker or sign. I’d veered off the beaten path long ago, and the trail was now narrow, the rhododendron closing in. Hot with each step, the skin at the back of my heel began to burn. I hiked on, meandering through a maze of rock, leaf, and wood. Some questions took root: Where on Earth am I? How much farther? Why did I decide to leave the main trail? Why did I decide to do this alone? Foot in front of foot, my head drooped, I began familiarizing myself with the tops of my boots, each nick and chink where rock and wear had gnawed the rubber rand around their soles. Boot in front of boot. Endlessly upward. I raised my head. The sea of rhododendron and laurel parted, and I could see an opening. I pushed hard through the thicket, only to jerk to a stop using my tiptoes to stay on the narrow ledge of a rocky outcrop. For the first time in a while, squatting there, I took a long look up.

The view before me perfectly explained how the Blue Ridge Mountains got their name — their rich hue running a little deeper than the adjoining sky. Carefully, I crept to the edge and looked at the valley floor far below. I knew the tiny treetops I saw belonged to hemlocks, pines and oaks at least 60 feet tall, but my brain couldn’t quite process that. The wind blew, and I thought it best to sit. From my perch on that crag of Whiteside Mountain, I drank it all in, forgetting about my earlier questions.

Wildcat Ridge of Whiteside Mountain taken from Bear Pen Mountain in Highlands, North Carolina, 1929. Opening spread: Sea of Views, Satulah Mountain, Highlands, North Carolina, 1929.

That summer, I was an intern for the local weekly paper, The Highlander, in Highlands, North Carolina, a town nestled on the southwestern edge of western North Carolina. My job, as best I could tell, was to complete any and all assignments given to me by deadline. After that, my editor explained, I was free to roam and photograph as many trails as my body and time would allow. I wanted to walk them all. I photographed vistas and wildflowers, rivers and creeks, crevices and creatures. I interviewed rangers and fellow hikers and followed maps — often veering from the path to explore the wilderness on my own. That was the summer I fell in love with those mountains, their clear and cool waters, their flame azaleas, their wildness. I fell in love with their damp scent — a scent known only in a forest tested by time. For the first time, I felt their raw, restorative power. I felt their freedom. It was at that moment I realized the true importance of nature, of silence, of sitting, breathing, and taking a full moment to look up — and to really see the world around me.

Fast-forward several years. I had finished college and worked my way back to Highlands, becoming the publisher and editor of that same weekly paper. I had recently seen Paul Bonesteel’s documentary “The Mystery of George Masa.” The documentary told the largely unknown story of Masa, a Japanese immigrant photographer whose work in the late 1920s and early ’30s was influential in the creation of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Since returning to Highlands, I had also heard that the local historical society had some of Masa’s photos on display. So I soon found myself in the basement of a small and nondescript but neatly kept building a few blocks off Main Street, looking at the largest known body of work by one of the most important and influential conservation photographers of our time. I loved my job.

The energetic and engaging Highlands Historical Society archivist took me through the collection of Masa photographs he had so diligently worked to digitize and preserve. In the world of publishing a weekly newspaper, you can only hope to be so fortunate as to have a person like Ran Shaffner in your community. The former professor, bookstore owner, and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill graduate was like an encyclopedia of the town’s history. When it came to Highlands, Google was not needed, you only needed to call Shaffner. His book, Heart of the Blue Ridge: Highlands, North Carolina, was the culmination of decades-long, meticulous research on the community and its people. It became my desk reference, and I felt fortunate to call Shaffner my friend.

Although very little is known about the life of George Masa, the impact of his work proved to be monumental in the creation of Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Over the last decade, Shaffner has continued his research, hoping to find out more about Masa and his work, to help shed more light on the photographer, providing the recognition he so rightly deserves. In a recent presentation, Shaffner unfolded the story of Iizuka Masaharu, his transformation to the photographer now known as George Masa, and how the historical society came to this collection.

As Shaffner explained, documentarian Bonesteel was regarded as the authority on Masa. Ken Burns had also included Masa’s work in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park portion of his PBS series on America’s national parks system. But, as Shaffner pointed out, if you asked either Bonesteel or Burns about Masa’s life before 1915, they would tell you it’s a mystery. There’s no record of Iizuka Masaharu living in or working in the United States before 1915.

“But we know that a man’s life doesn’t have to be documented for his own claims about it to be accepted as true,” Shaffner said. “So until it’s proven otherwise, I’ll rely on Masa’s journals, his letters, the census, his death certificate, and what he has himself told us about his past.”

Cliffs of Whiteside Mountain, straddling Jackson and Macon counties, North Carolina, 1929. Nature journalist Horace Kephart said Masa liked to photograph “terra incognita” (unknown or unexplored territory). Masa often risked his life to capture a scene completely, as displayed in this photograph of the sheer cliffs of Whiteside Mountain, a summit that forms part of the Eastern Continental Divide in western North Carolina.

Shaffner said Masa once told a newspaper reporter that he was born in Osaka, Japan, and his death certificate said he was born on January 20, 1881. Masa said he moved to Tokyo to go to college and study at Meiji University. While there, Masa met a Methodist missionary. Shaffner said this meeting greatly altered Masa’s course. He converted to Christianity and changed his given name from Iizuka to George. Shaffner said that since family names in Asia are often placed before given names, his name would have then been Iizuka George.

Shaffner said the missionary spoke with Masa about the United States, and at age 25 Masa stole passage on a ship to San Francisco. There’s not a record of Masa’s passage on a ship, Shaffner said, but, “If he stole passage, would there be a record?”

According to the 1930 census, Masa immigrated to the United States in 1906. He then entered the University of California to study mining engineering. Masa’s journal tells us he left San Francisco on January 18, 1915, traveling by train to New Orleans and St. Louis. Later that year, on July 10, Masa arrived in Asheville, North Carolina, with some Austrian friends and began working at the massive and newly minted Grove Park Inn, Shaffner said. Masa first started in the laundry, then moved to bellhop, and then to valet. It was at the Grove Park Inn, Shaffner said, that Masa shortened his name from Masaharu to Masa, saying it was for convenience.

Masa is said to have taken lots of hikes in the area with his Austrian friends, also taking guests of the inn on hikes and picnics. One day, the manager of the inn loaned Masa his camera to capture photos of the area that could be used to help promote the inn. At this critical moment, Masa’s life altered course once again.

Bridal Veil Falls, Highlands, North Carolina, 1929.

While working at the inn, Masa connected with and made photographs for many of the wealthy and influential families in Asheville at the time — the Vanderbilts, Groves, and Seelys. But in 1917, Masa grew tired of working at the inn and headed for Colorado Springs to prospect for gold, Shaffner said. While Masa did not find his fortune, the grandeur of the Rockies made an impression. Masa returned to Asheville and the inn, but asked for any job except valet. A few stories published earlier this year allege that Masa experienced anti-Asian discrimination while working at the inn. However, Shaffner says Masa’s usually open and candid journals make no mention of any such incidents.

Masa left the inn for the final time in 1919 and began working at a local photo shop. In 1920, he opened his own photo shop called Plateau Studios. Masa then sold this business in 1924 and opened Asheville Photo Company in 1925. Shaffner noted that one of the ways to identify a Masa photograph is by the stamp on the photo. It will say Plateau Studios or Asheville Photo Company. In 1924, Masa also began making movies for the Asheville-Biltmore Film Company and worked for Paramount and Pathé as a newsreel photographer for all of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Tennessee. But Shaffner said none of this work has been found.

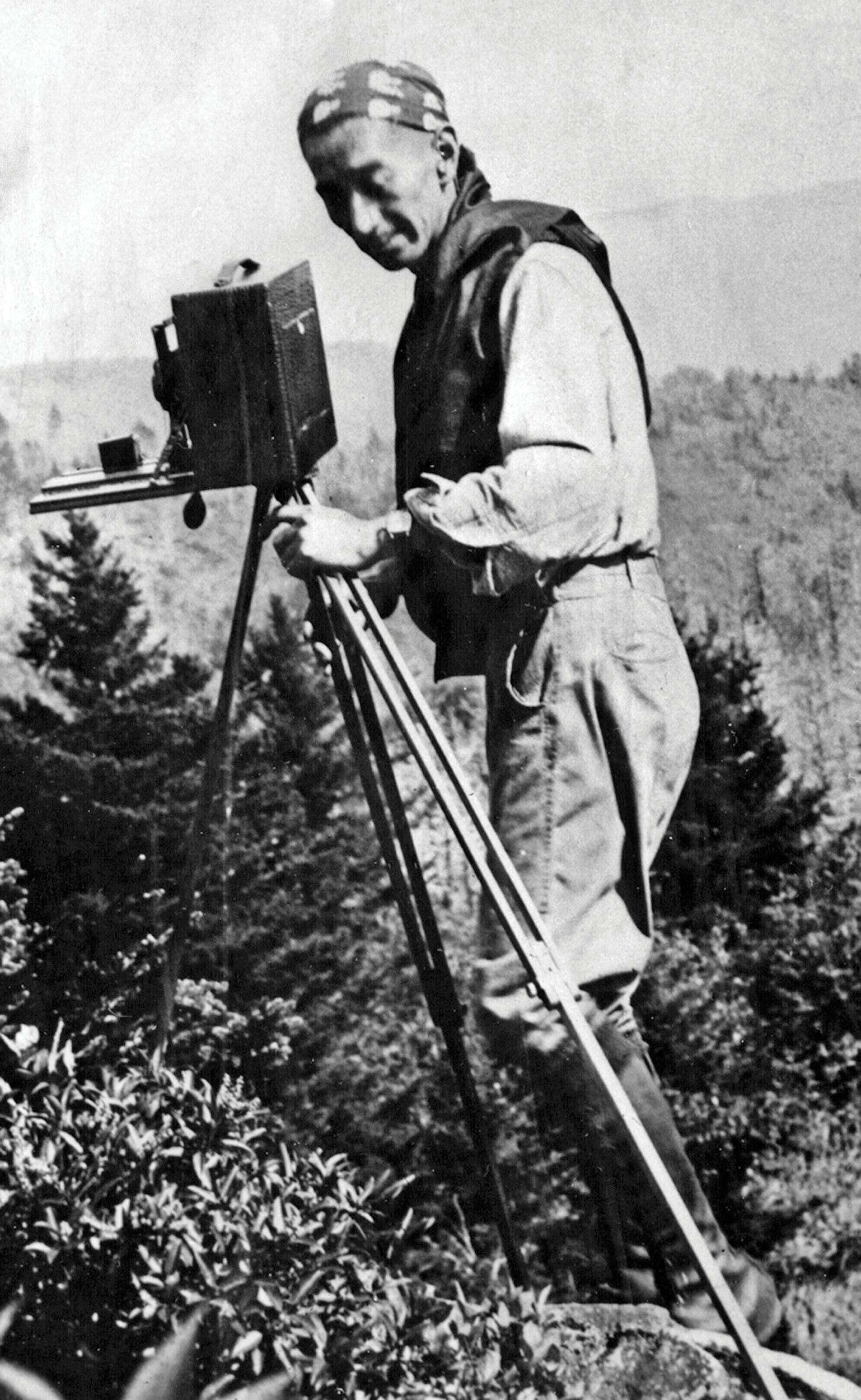

Masa has been described as a friendly and gentle soul, but the environment he photographed was not. Masa was an inch or two over 5 feet tall and weighed a little more than 100 pounds, Shaffner said. Lugging a heavy, 8-by-10-inch view camera with a wooden tripod on his back, Masa hiked the many miles it might have taken to find the right spot for the perfect shot, traversing the Smokies eight to 10 years before there was a map of the Appalachian Trail. Shaffner said Masa was devoted to accuracy and mapped hundreds of uncleared trails in the southern Appalachian Mountains. He eventually mapped the part of the Appalachian Trail from North Carolina’s border with Virginia all the way to Georgia.

Masa’s meticulous nature in photography carried over to his cartography. Since he was a trained engineer, Masa created a contraption to ensure his hiking distances were measured accurately, Shaffner said. He removed the seat, frame, and back wheel from a broken bicycle and attached an odometer to the handlebars. Masa then pushed the handlebars and wheel in front of him as he walked. This “cyclometer” helped him record the proper distances as he mapped each of his routes.

In the mid-1920s, Masa first met librarian turned author and nature journalist Horace Kephart, whose book Our Southern Highlanders offered an intimate portrayal of the unique people living in the Smokies. At the time, Kephart was horrified by the immense scale of the commercial logging that was taking place in the grand forests of the region, Shaffner said. Kephart began writing a series of articles for publications across the nation, detailing what was happening in the world around him. While working on a story for National Geographic, Kephart needed photos and hired Masa to help. The kinship between the two as they worked to preserve the Smokies was instant. Kephart’s writing paired with Masa’s photos proved to be an influential tool in the creation of the park. Working together, the two mapped and named many of the peaks for the future park as well.

Shaffner said Masa was promoting the Smokies as a national park as early as 1925, a good nine years before the park existed. In 1933, Masa published a guide for the Smokies, and the guide proved to be so accurate that it corrected the U.S. Geological Survey maps at the time, Shaffner said.

Rhodes Big View, taken from Cowee Ridge in Macon County, North Carolina, 1929. “Masa would find a view that he wanted and set up his camera until the light was exactly right,” says Ran Shaffner, archivist emeritus for the Highlands Historical Society. “Even if that meant sitting for an hour, or two hours, or three hours, or a day, or a few days, or coming back another day for another shot.” Shaffner pieced together three of Masa’s photos to create the panoramic view above.

For nearly two decades, Masa honed his craft. His patience and passion are preserved in his photographs. In 2009, Kent Priestley wrote about Masa for Mountain Xpress, a publication in Asheville, describing Masa’s best photos as being full of “deep shadows and penetrating light.”

About one photo of the Black Mountains, Priestley writes, “A bank of clouds hovers slightly over the distant peaks, admitting enough light to touch off the horizon in a bright glow. Sunlight rolls down the valley floor, arrow-like, ending at the dark cleft that shadows the foreground completely.”

While taking pictures for Kephart in 1929, Masa was also hired by Frank Cook, who owned and operated Highlands Inn. Cook wasn’t turning much of a profit at the time, but, like the manager of the Grove Park Inn, thought Masa’s photos could help him promote the area. Cook offered Masa free room and board and cash for expenses, thinking Masa would come and stay for a few days, take some photos, and leave.

“But Cook didn’t know Masa as the consummate professional that he was,” Shaffner said. “Masa would find a view that he wanted and set up his camera until the light was exactly right — even if that meant sitting for an hour, or two hours, or three hours, or a day, or a few days, or coming back another day for another shot.”

A week passed, and Cook was in a quandary. Masa’s stay was taking much longer than anticipated. But after two weeks, Masa presented Cook with nearly 100 photos of the area’s mountains, vistas, roads, homes, forests, and waterfalls.

“You can’t always tell from a photograph what the artist has had to endure to get his perfect shot,” Shaffner said. “Sometimes Masa would leave Highlands Inn at 3 a.m. and sit in the cold and rain, waiting for ‘the precise atmospheric moment,’ when the sun would rise or set. There’s a tremendous sacrifice in making a photograph a work of art.”

Beverly Cook Quin, daughter of Frank Cook, carefully kept the Masa photos in their original album. She shared the album with Shaffner and later donated all 96 photos to the historical society.

Masa’s work should have made him a fortune, but his photography business struggled. Shaffner said Masa lost what little he had in the bank in the crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression. Then, in 1931, Masa lost his best friend, fellow advocate, and collaborator when Kephart died in a car crash.

“Kep is gone forever! His death shocked me to pieces,” Masa wrote in his journal. “I never experienced such feeling in my life. But we must keep going on what we have in our hands, and I like to carry out what Kep wanted.”

Two years later, on June 21, 1933, at the age of 52, Masa died of tuberculosis and other complications. Shaffner said he should have died wealthy, but instead died penniless and in debt. Masa’s friends helped pay for his funeral. Masa wanted to be buried near Kephart and the future park in Bryson City, but was buried instead in Riverside Cemetery in Asheville. Shaffner said friends tried to move Masa in the early 1940s, but World War II was raging, and Masa was never moved.

Asheville photographer Elliot Lyman Fisher bought 6,000 of Masa’s negatives soon after his death, and Shaffner said Fisher first sold photographs under Masa’s name, but later did so under his own name. He said Fisher moved to Florida in the 1950s and died in 1968. Those negatives have never been found, Shaffner said, meaning nearly all of Masa’s original work has disappeared. Without Quin and the historical society, a significant part of Masa’s work would be lost.

“Masa has been called the Ansel Adams of the southern Appalachians,” Shaffner said, “and it’s probably because of the photographs he took of the Smokies, which produced a social change. Masa’s most powerful weapon was his camera. He used photographs instead of words to help people understand and change.”

Kephart said Masa liked to photograph “terra incognita” (unknown or unexplored territory). “There were scenes in the Smokies which probably no man had ever witnessed because of their inaccessibility,” Shaffner said. “But Masa would find those scenes and risk his life photographing them.”

Top of Glen Falls, East Fork Overflow Creek, Highlands, North Carolina, 1929. Lugging a heavy camera with a wooden tripod on his back, Masa hiked the many miles it might have taken to find the right spot for the perfect shot, traversing the Smokies eight to 10 years before there was even a map of the Appalachian Trail.

A year after his death, Masa’s dream of a park materialized. John D. Rockefeller Jr., who knew Masa and had seen his photographs, gave $5 million to purchase the land for the park. But it took another $1.5 million of federal funds before the park was finalized. President Franklin D. Roosevelt later dedicated the park in 1940, and in 1961 the park dedicated Masa Knob, a 5,685-foot peak adjacent to Mount Kephart.

When Masa felt lost and disheartened, he once wrote in his journal, “I go into woods, get fresh balsam air, then come back and start strong, good fight.”

In a year wrought with sadness and hardship, many of us looked to the great outdoors for grounding and peace. We lost loved ones. We ached as we felt the fabric of our country rip. We sought solace in whatever way we knew. For many, the pandemic turned our focus inward to ourselves and our immediate families. In return, we flooded the natural open spaces of our parks. I found myself once again walking those familiar mountain trails. But this time, I was not alone. My wife and I laughed as we watched our children shiver in those cold waters, content as they explored, flipping over rocks, delighted at the creatures and natural world before them. We climbed Whiteside and held their shirttails tightly, allowing them to carefully peer over that outcrop’s edge. We sat and drank it all in.

Today when I look at a Masa photo, I see his demand for perfection in its detail, his desire to capture the scene — its complexity and beauty — completely. But as I think more deeply, I see Masa’s desire to save that scene, to preserve it indefinitely, leading me to think that it may have meant more to him than just saving the forests. I’d like to think he knew that saving some natural space, some wilderness, would also help us heal, ultimately offering us a way to save ourselves.

Eric NeSmith comes from a long line of storytellers, but community journalism has been his passion since childhood, seeping into his veins through his fingertips as he inserted the sections of his hometown paper together at 8 years old. His career in journalism has spanned reporting, photography, marketing, editing, and publishing. He is the publisher and CEO of The Bitter Southerner.