Through photography and warm meals, Susan Adcock builds relationships with Nashville’s homeless population. She’s trying to work herself out of a job.

Story by Jennifer Justus | Photos by Susan Adcock

August 10, 2021

It’s kind of a long story.

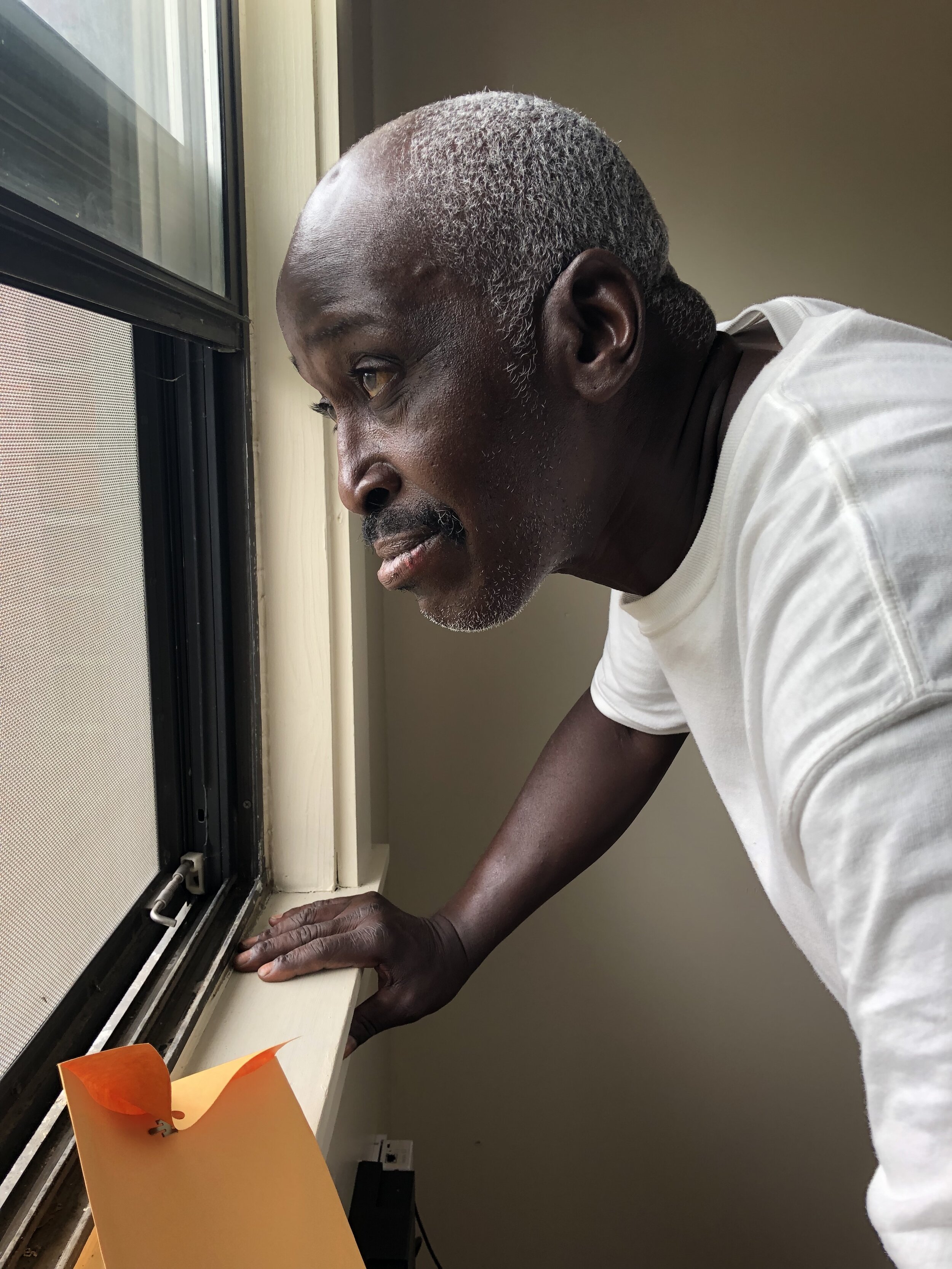

I slept in the parking garage for a couple of months. A guy named Bruce had an office in the building. He kind of befriended me. Brought me some food now and then; gave me a dollar or two. Then he said, “Hey, have you ever heard of a lady named Susan Adcock? She can really help you.” I didn’t have a phone at the time. So I asked if he could get in touch with her for me. He said he’d be glad to.

I think it was the next day. I was asleep. Susan came over and introduced herself. She said, “Are you hungry?”

I said, “Yes, ma’am, I’m very hungry.” She gave me this big platter of food.

I was drinking around the clock. My whole world revolved around vodka. Nothing else mattered. If I had a choice to eat or to drink, I’m gonna drink. I’d go days without food. But Susan would come around and bring me some food. Then I got kicked out of the garage because the owners complained. I had to relocate. Went over to the park and started sleeping under the trees. Ms. Susan has several people she helps in the park. So she naturally progressed to me. “What are you doing over here, Tony?”

I’m like, “Well, I got kicked out.” She still helped me out. She really encouraged me and told me I could turn my life around.

— Tony D., age 58

Nashville, 11:45 a.m.

Susan Adcock pulls her car to the side of a busy street in Nashville where a man works the corner with The Contributor, a street newspaper often sold by those living with homelessness in Nashville. She shouts his name out the window. “You want some food?” He does.

Adcock flips on the hazards and loads up some individually portioned servings of chicken pot pie with roasted green beans. As she hands them over, the conversation quickly turns to the man’s friend, also homeless, who had been hit by a car and would soon need surgery. Could Adcock help?

The meals were like an offering to trust, a portal to a deeper place and a complex web of problems, challenging the systems that made the sharing of the meals necessary in the first place.

Adcock notes the needs, and as she starts to drive away, she asks The Contributor salesman if he’d seen a man named Tony. She shows him a picture on her phone.

Nope.

Adcock works as a street outreach and resource navigator with a nonprofit called Open Table Nashville. When she drives through the city on her 10-hour shifts, her eyes scan a horizon below the neon signs that draw tourists and the towering cranes erecting high-rises. She looks for the many folks who live in the shadows and cracks, in the alleys, bus stops, and underpasses of Music City, USA.

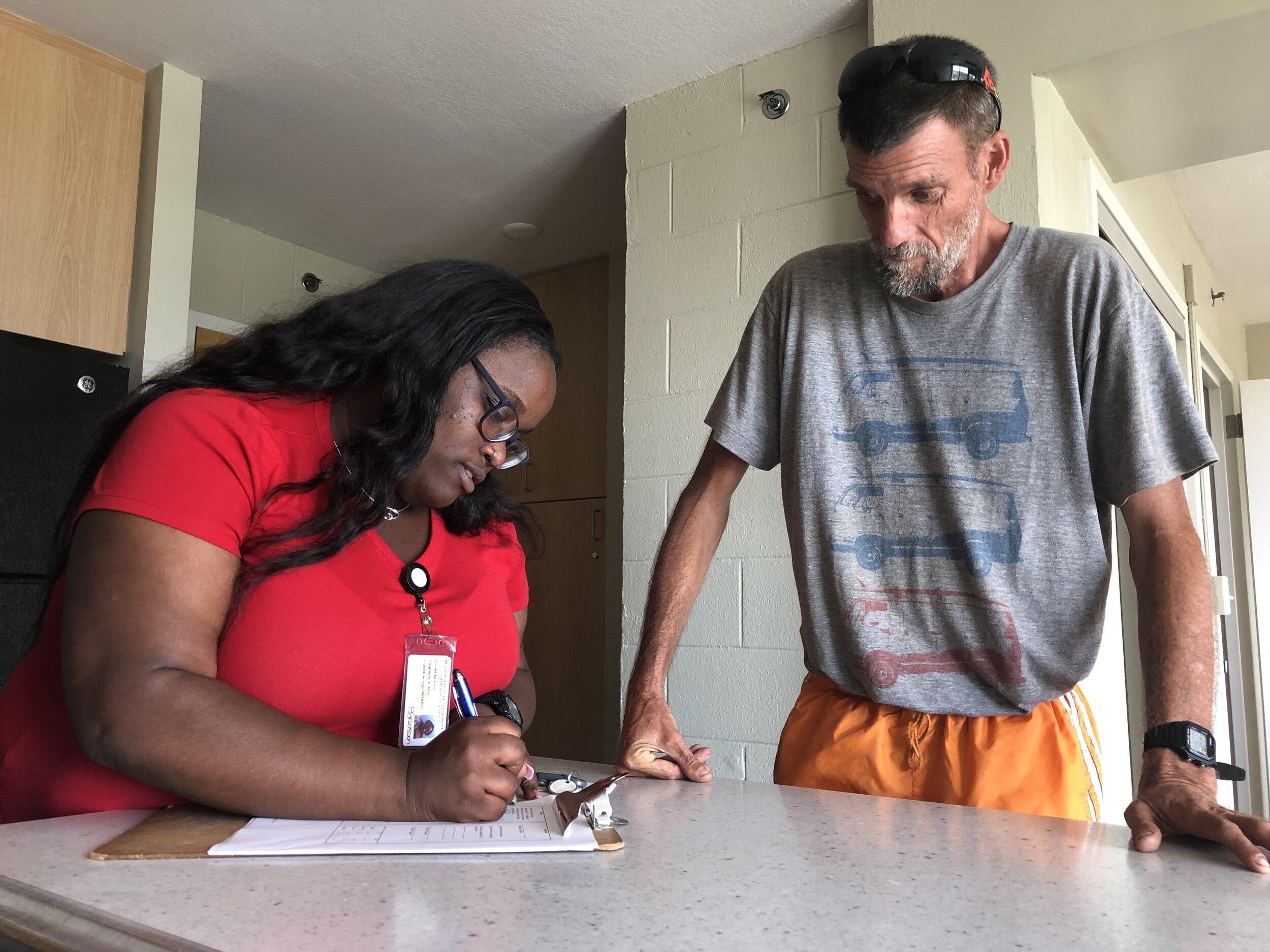

“I help people with anything they need if they’re living outdoors,” she says. That might mean helping procure food stamps, camp supplies, body lice medication, or documents for housing, a process that can take six months to two years. In the five years she has been doing this work in an official capacity, she says she’s helped 70 people into stable housing. “I can’t not count,” she says, “because it’s really the only thing I’ve got.”

She got into this work in the 1990s in part due to photography, a job she worked professionally for many years and continues to do on the side. “I just took pictures of people and listened to them. A big thing that’s missing for people out here is that nobody really listens to them.”

Through her street photography, she began advocating for folks. Then, later, with Open Table, she took on the work in a more official capacity. Good photography, after all, is about connection. To make a photograph can be a way of saying to a person: I bear witness, and your image and story is important and worthy of being seen, recorded, and remembered.

Adcock uses her iPhone more often than a camera because it's a device that's more familiar. “This particular group carries a fair amount of discomfort starting out, and I’d rather not add to that if I don’t have to.” She only photographs folks who give her permission, and she respects people’s wishes if they decline.

Adcock traverses a Nashville that many people don’t see or that they ignore — out by the dumpster behind a McDonald’s or behind wrapped chain-link construction fences. As real estate prices soar and new residents flock to this city, Adcock says the construction barriers offer some privacy for many of the people she sees who need to doze during the day. She explains how they need to stay awake all night to keep folks from stealing the shoes off their feet, to protect their own body and their few belongings.

Still no Tony. She has not seen him in weeks but memorized what he wore, a trick she uses to spot folks from a distance.

Adcock will never forget Ralph, or “Maz” as people called him, one of the first people she got to know through this work. Maz had come to the United States from England for school at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he graduated with a degree in architecture. But he also endured severe mental illness and threw away his IDs and passport to “live like Jesus.” He died in a van fire while parked inside a warehouse. Afterward, Adcock found the book he had published years earlier on passive solar heating. “He was a really smart guy,” she says. “Everybody is so different out here.”

It’s one of many misconceptions about homelessness Adcock pushes against. “People sort of group everybody in the same category,” she says. “But everybody has their own issues.”

A partnership between Open Table Nashville and The Nashville Food Project grew out of the coronavirus pandemic when many of the communal-style dinners had to close. Now, outreach workers like Susan Adcock deliver scratch-made, individually packaged meals into homeless camps and onto the streets.

Adcock will offer about 20 meals during her shift, while bearing witness to an array of troubles. An amputee in need of medication, wincing in pain. Another person seeking access to a cellphone because he misses his dad. A man with a “One Love” sign painted on cardboard waiting on $20 from The Contributor, which had published one of his poems. He says he learned to write during his second stint in prison.

“Probably the biggest misconception is that people want to be homeless,” Adcock tells me. “That’s never, never the case. I think there have probably been people who said, ‘I choose to be out here.’ But ultimately I think it’s easier to say that than say, ‘Here are the 10 horrible things that happened to me in my life.’”

Also, getting into housing is just about impossible, she adds. “Say they work a job and manage to live in their car. They can’t very easily get their own place. It takes too much time and energy and resources and phone calls — especially since COVID.”

The partnership between Open Table and The Nashville Food Project, the nonprofit that provides the meals, grew out of COVID when many of the communal-style dinners from churches and other groups across the city had to close for safety reasons. Outreach workers shifted to a model of delivering scratch-made, individually packaged meals into camps and onto the streets.

In addition to the pandemic, Nashville had a tornado and bombing in 2020, which were particularly hard on the homeless population. The Tennessean reported that more than 130 people from the homeless community in Nashville died last year, the highest annual death toll in the city’s recorded history. Then, with flooding this past March, two folks living in a camp died, including a veteran who had been in a wheelchair. It’s a reminder of the days when the historic 2010 flood in Nashville swept through Tent City, a place where about 140 people stayed. City leaders declared the space “condemned,” which excluded it from public assistance and prevented folks from returning.

The clearing of camps continues, including a controversial camp closing downtown in June, where Adcock says about 20 to 100 people might have lived at one time. While the city said the closure is due to crime and public health concerns, Adcock believes the pressure may have come from developers. Earlier in May, police shot and killed 23-year-old Jacob Griffin, a severely mentally ill man, during a standoff at an encampment in South Nashville. At a public vigil for Griffin, Open Table co-founder Lindsey Krinks says they gathered to mourn his life and “speak into a system that is not just,” and to speak for alternative forms of care, such as affordable housing, an investment in mental and physical health care for all, a living wage, and protections for tenants and workers.

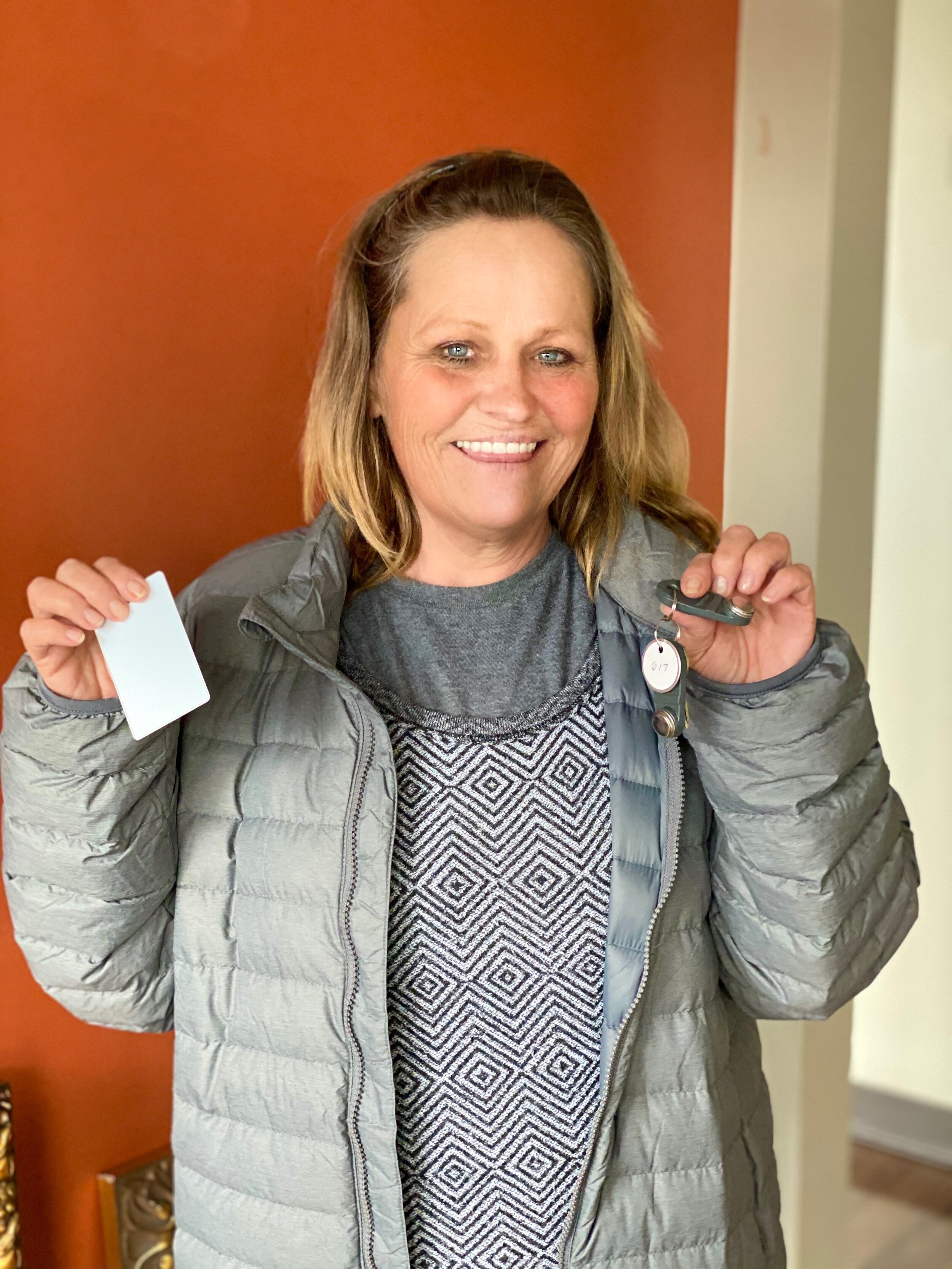

“It comes back to not enough housing,” Adcock says. Even as Nashville expects an influx of low-income housing vouchers due to the American Rescue Plan, there are still too few units available that will accept them, due in part to hypergentrification. “[Housing is] the answer to nearly every problem for folks even though it’s not perfect or easy.”

Krinks also says one of the most effective ways of ending homelessness happens through the Housing First model. It provides housing and support services to people before requiring them to have stable employment, sobriety, or their mental and physical health issues managed. “This model understands that housing is a human right,” she says. “Housing is health care. Housing is the foundation of healthy individuals and communities. And providing housing is both more humane and cost-effective than keeping people on the streets.”

“Everybody is so different out here,” Adcock, a street outreach and resource navigator for Open Table Nashville, says. It’s one of many misconceptions about homelessness she pushes against. “People sort of group everybody in the same category.”

Around 1 p.m.

Adcock pulls into a local park, beeps her horn at some folks she knows. “Talking to the dope man,” she whispers to me as an aside. She opens her hatchback to reveal a free mobile thrift store of coats, jeans, shoes, meals, Narcan kits, condoms, and first aid.

“Fuck, yeah,” says one man as she hands him a pot pie. Adcock listens to his concerns as he eats.

She says folks respond and share more freely about their struggles when she carries hot meals rather than cans of Vienna sausages or granola bars. “On the street, people are forced to rely on cheap, accessible food to survive. The long-term effects are visible in emergency rooms all over town,” she says, citing the increased rates of Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease related to a lack of stable or adequate housing.

More nourishing food, she says, improves quality of life but also gives folks something to look forward to. “It lifts their spirits and indirectly got some of them into housing,” she says. “Passing out food caused me to meet people I might have otherwise missed.”

* * *

Before you’re old enough to go to school, you’ve got to stay somewhere. Well, my mom and my dad both worked, so I stayed with my Granny Smith. She was my great-grandma. She lived in Fairview, Tennessee. I remember this like it was yesterday ’cause I love my Granny and she’s been gone for 30 years or so. … She said, “You’re ready to go squirrel hunting.” I was 4 years old. “Go down in them woods and knock us out a couple squirrels, and we’re gonna have squirrels and dumplings for lunch.” So here I took my rifle. I missed a few. I finally hit one. Missed another. She told me to get two. I went screaming back to her, “Granny, Granny, Granny, I got ’em.” You talk about a proud little boy. Then we had the most wonderful meal of squirrels and dumplings that you could ever imagine.

— Tony D.

Adcock began working with the homeless community in the 1990s, in part due to photography. “I just took pictures of people and listened to them,” she says. “A big thing that’s missing for people out here is that nobody really listens to them.”

If people on the street call comfort food like chicken pot pie a favorite, it also has been a favorite at The Nashville Food Project kitchens for its adaptability. The Food Project took in or saved about 220,000 pounds of food from the landfill last year from sources like groceries, farms, or conferences. If an extra pallet of asparagus comes through the doors, it will be chopped and folded into the chicken pot pie in place of carrots or peas. A recent meal for Open Table included peppers that needed to be moved from the shelves at Costco; kale, broccoli, and bok choy from local farms; and mushrooms and beef from the local food bank, Second Harvest. The result, a vibrant stir-fry, showed how a meal of perfectly good but cobbled-together ingredients — that others might throw out or see as worthless — could be transformed into a scratch-made meal served with dignity.

Meanwhile, though, it’s no secret that all the good food in the world won’t solve hunger or homelessness. If food transcends more than sustenance or a temporary patch until the next meal, it works best when served in tandem with other individuals and organizations working in various ways to disrupt poverty. Rather than being served “to,” they are served “alongside” — blurring the lines between guest and host.

“At one point in my life, there was this idea that if I used my photography to illuminate or expose or educate enough people about a social injustice, that someone would step up and do something about it, and of course that didn’t happen. Instead, they would look at the photo and they’d say, ‘Wow, this is a great photo.’ And that’s as far as it went,” Adcock tells me when I ask how she went from documenting people’s lives to direct advocacy. “One day I said to myself, Why don’t you do something about it? Why don’t you step up?

“Now, I know that I haven’t effected any widespread change with regard to homelessness, but I do know that for Roger or Brad or a number of others, things did change, because I learned to be tenacious.”

Adcock recently started a TikTok account to document stories from the street. Sometimes they’re funny (like when she rattles off the many street nicknames, like “Cheeseburger” and “Hamburger”). Other times they reflect sadness or anger. “Everyone gets tired of it,” she says in one video. “Tired of it? Call your legislators.”

* * *

My mom and dad were both very loving and supportive. But they didn’t like each other. They got divorced when I was 16. Most teenagers, when their parents get divorced, they’re just crushed. But it was one of the happiest days of my life. ’Cause I didn’t have to listen to all that arguing.

I went to college for two years. Dropped out. Thought I was so smart and didn’t need college. I finally got a really good job. We made really good friends in college. Hunting and fishing buddies. He started his own construction company, which was highly successful. We only worked in Belle Meade.

When my boss retired, I lost my $30-an-hour job. I went around to all the competitors [but couldn’t find work]. ... That’s when I started drinking. Probably 10 years ago. I had to give up my fishing. When I was fishing, I had my TV show (“Fishing Country”). I had sponsors — boat, baits, rod, reels. Went to Texas and filmed a show, went to Florida and filmed a show.

My dad passed about four years ago. We were very close. As I entered adulthood, we became like brothers. My mom, I either text her or talk to her every day. ’Cause I went all that time when I was drunk without a phone. I’d get on the bus and just beg somebody to let me use their phone so I could just say, “Hey, Mom, I’m alive.”

“You’re drinking, ain’t you?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

There’s a big misconception that all homeless people are out to rob you, and that’s true of some homeless people, but that’s true of some people in any walk of life.

The vast majority of homeless people are just good people that have a problem.

— Tony D.

Open Table Nashville co-founder Lindsey Krinks says one of the most effective ways of ending homelessness happens through the Housing First model, which provides housing and support services to people before requiring them to have stable employment, sobriety, or their mental and physical health issues managed. “This model understands that housing is a human right,” she says.

Close to 3 p.m.

As morning stretches into afternoon, Adcock only has a couple of meals left to give as she drives toward the wealthy neighborhood of Belle Meade. Then, as she nears Ascension Saint Thomas Hospital, she spots a black lightweight windbreaker at a public transit stop. She honks and leans over to shout out the passenger window: “Don't get on that bus!”

Tony's eyes light up as he recognizes her. She whips into a Taco Bell parking lot the wrong direction and then rushes toward Tony with his meal. “I can’t miss this bus,” he says. He has an appointment with a new therapist and can’t afford extra bus fare or the time in rescheduling. Adcock delivers Tony his meal along with the news that she’s found a room for him. His mouth drops open. They make arrangements for Adcock to meet him in a few days at the Nashville Rescue Mission with a new case manager who will help with the move. “It’s Tuesday, right?” Tony asks. And then the bus comes, carrying him off in a whoosh.

“I wish the job didn’t exist,” she says, “but I will consider this a great day, because I didn’t expect to see him.”

It was, I believe, on a Friday. They said meet me over here at the mission. … It’s all because of Ms. Susan. I owe her my life.

I hope that I can get a decent job. I’m not looking to get rich. Eat. Have a place to live. That’s about it. Every human being has to eat. That’s a basic necessity. You can survive in a garage or under a tree. It’s a hard life. But you gotta eat.

It’s things that people never consider about homeless people. Like not having a pillow. I cannot describe to you how it feels to lay down in my own bed with a pillow. I’m just so grateful for a pillow, because I went so long without one.

— Tony D.

Jennifer Justus works as a storyteller for The Nashville Food Project and is the author of Nashville Eats: Hot Chicken, Buttermilk Biscuits, and 100 More Southern Recipes From Music City. Her work has been published in two editions of Cornbread Nation: The Best of Southern Food Writing, and she has received national awards from the Society of Features Journalism, Society of Professional Journalists, and the Association of Food Journalists. She worked for six years as food culture reporter and features writer at The Tennessean newspaper and has written for outlets including Time, Rolling Stone Country, Southern Living, and Garden & Gun. For The Bitter Southerner, she’s written stories about groaning cake, Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, and country music cookbooks. Justus is co-founder of the recipe storytelling project Dirty Pages. She can be reached on Instagram (@jenniferjustus8) and Twitter (@jenniferjustus).