Watermelon, that most thirst-quenching of fruits, has long nourished the imaginations of American painters. Shane Mitchell traces the visual evolution of its status as the bravura of still life to its weaponization as a racial trope to the triumph of artists who are reclaiming it from infamy.

by Shane Mitchell

August 23, 2023

“Watch out,” I said. “You’re way too close.”

My youngest sister’s index finger hovered within an inch of the 200-year-old oil painting.

“Hilary! Seriously, don’t point!”

We grew up stretching canvases and cleaning sable brushes in our father’s studio, so we were dangerously comfortable touching important works of art, but the curators at Harvard’s Fogg Museum would have preferred that we keep a respectful distance. At the moment, no security guard lurked in the third-floor atrium, and the two of us shared a pair of cheaters to examine airy brushstrokes limning flesh as ripe and luscious as the red-hot lipstick worn by my first Barbie doll.

The perspective was amateurishly askew, the composition primitive, especially compared to ostentatious banquets once tabled by Dutch Baroque masters. Yet not bad for a 20-something apprentice starting out in Baltimore, Maryland. I opened a website on my phone and zoomed in to compare a starker still life, also painted in 1822 by the same early American artist, that recently sold at Christie’s for $277,200. The auctioned version was boldly centered on a blue-rimmed plate, with a juicy chunk fallen to the side, devoid of the dainty peaches and curling grape leaves obscuring the more conventional rendition facing us in the Fogg. Yet both represented a visionary expression of joy for the fruit that only decades later would become a tool of systemic racism. Until artists across the South eventually created their own celebratory interpretations, seeking to reclaim power and ownership over one of our greatest visual feasts.

“See that?” Hilary said, waving her hand at blobs of paint. “Look how she used those tiny white dots to highlight the seeds.”

A single seed clung to the pale green rind, slipping wetly from the exposed heart of Sarah Miriam Peale’s broken watermelon.

Sarah Miriam Peale, Still Life With Watermelon. Courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum. (Top) Sarah Miriam Peale, Watermelon. Courtesy of Christie's Images Limited.

Much like me and my siblings, Sarah Miriam Peale was born into a multigenerational family of white artists. While most of the Peales churned out portraits of prominent socialites, politicians, and Revolutionary War heroes, Peale’s cousin Raphaelle was the first notable American to focus on still life when it was snobbishly dismissed as a subject for amateurs. In her teens, Peale, affectionately known as Sally, apprenticed with her father, James, in Philadelphia, mixing his paints and adding her own brushstrokes to lace, flowers, and other portraiture details. She then shared studio space on the third floor of another cousin’s museum and gallery in Baltimore. In a letter posted on December 16, 1819, Rembrandt Peale reported her progress: “ … you will be surprised to see how much Sally is improving. Consequently she will become more industrious and I think it is very probable that she will find employment in Baltemore [sic].” In an era when women of a certain social standing were morally suspect if they worked for their livelihood, Peale became the first truly successful female commercial artist in America.

She also never married.

One of her cousins once commented: “Sally is as usual breaking all the beaus hearts & won’t have any of them.” Beyond that suggestion of an independent spirit, few original details exist about her personal life, as none of her own correspondence has survived, although a self-portrait at age 18 highlights violet-blue eyes and dark curls, with rosy cheeks matching her crimson velvet shawl. Three years after her melons, Peale’s father painted a similar study, with grapes scattered like marbles and a peach sliced in half, framing a less appetizing gourd. Not quite a copycat, but perhaps a wink-wink for his protégé.

In 1847, Peale left her family behind and set up a portrait studio in St. Louis, Missouri, a boomtown that solidified its status as a “Gateway to the West” when gold was discovered in California. During the Civil War, when the state seesawed its loyalty between Union and Confederate camps, Peale took up still life painting again. In 1878, however, she returned to Philadelphia to reunite with three other sisters, artists in their own right.

What would she think about her painting selling for a personal record price almost 150 years after her death? Not her dainty baskets of raspberries, bowls of ripe cherries, glossy bunches of grapes, peaches rolling, scattered on a table.

A big-ass chunk of watermelon.

“It really could own a wall,” said Caroline Seabolt, a specialist in American art and head of sale for the Christie’s auction that included Sarah Miriam Peale’s painting. When we spoke about the significance of the painting, she emphasized that while Peale was so young in 1822, her singular aesthetic and voice were already evident, even within a dynasty of talented painters. “It literally has a juicy quality, in the vibrant colors of the melon.”

Then she added something that gave me pause for thought about the Peale fascination with fruit, not as a side hustle to their portraiture work but the breakthrough for an emerging American genre. The still life at the Fogg, with its addition of peaches and grape leaves, “is a formal study of the way natural objects interact with one another,” Seabolt said. “But the one we just sold? You’re looking at a singular portrait.”

The watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) is one of the few domesticated fruits whose place of origin remains a mystery. Archeobotanists speculate that a sweet relative grown in the Kordofan and Darfur regions of Sudan may be its progenitor. Other ancient varieties had bitter pulp, closer in taste to their cucumber cousins, and would never be destined for a Buc-ee’s frozen slushie or your Nana’s watermelon rind pickle. A quencher of thirst, the fruit is 92 percent water by weight, and for those toiling in the drought-plagued, semi-arid Sahel, it was often a lifesaver. The oldest remains yet discovered, from a 6,000-year-old wild watermelon, were found at a neolithic settlement known as Uan Muhuggiag in southwestern Libya. The seeds were cracked by human teeth.

But for art’s sake, it’s best to begin with the timeworn relief of a green-striped melon, painted about 2,000 years later by an unknown craftsman on the limestone walls of a pharaoh’s tomb in Saqqara, Egypt. It looks remarkably like the Georgia Rattlesnakes piled in the back of pickups at the State Farmers Market in Cordele, Georgia, self-styled watermelon capital of the world.

The journey, from there to here, across eons and oceans, was fraught.

Melon seeds crossed in the cargo holds of ships navigated by early Spanish and Portuguese explorers. Hidden in the hair of enslaved women, victims of the Columbian Exchange. Disseminated by missionaries and colonizers seeking fabled lost cities, silver mines, or simply conquest. (By 1576, Santa Elena, the first capital of La Florida, was reported as fertile ground for watermelons.) Carried overland on the vast network of Indigenous trade paths stretching west, adopted by tribes in the Mississippi Valley, the La Junta region on the borders of present-day Texas and Mexico, and Pueblo communities of the Four Corners.

Julian Martinez, Clown With Melons. Courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution.

Similar to its role in arid Africa, watermelon became a source of hydration in a harsh desert climate on the high mesas. For thousands of years, the Hopi practiced dry farming there, relying on rainfall and spring water to grow the Three Sisters — corn, beans, and squash — in the ceremonial calendar tied to Katsina, the Hopi religion, and when watermelon joined them, it was mentioned in prayers for rain during the planting season.

Hopi performers, known as paiyakyamu, performed ceremonial, communal dances to invoke favorable weather. They represented guardian spirits, expressly rainmakers. Between solemn ceremonial acts, they provided comic relief, committing acts of gluttony. Modern Indigenous artists depict these sacred clowns gobbling watermelon. A paunchy paiyakyamu in mid-dance and surrounded by Hopi sikyatko melons is featured in a watercolor by Julian Martinez of Po-Woh-Geh-Owingeh (San Ildefonso Pueblo) in the National Museum of the American Indian. Or maybe he’s sleepwalking in a dream state. In more graphic work, Hopi artist Rod Phillips shows Koshare, another name for this jester, clutching a hunting blade and melon under one arm while spitting seeds from a slice. Juice runs down his chin.

On a day when The Metropolitan Museum of Art was closed to the public, Sylvia Yount, Curator in Charge of the American Wing, walked me through to Gallery 762. This small room at the back of the museum — labeled Civil War and Reconstruction Eras and Legacies — is an assemblage of paintings and sculptures that create a visual timeline and emotional sounding board for one of our country’s thorniest turning points. A messianic portrait of abolitionist John Brown occupies an entire wall. A triptych of Black military service painted in 1865 and 1866 by Thomas Waterman Wood. The Augustus Saint-Gaudens bronze of Lincoln, standing with his head bowed. Union army veteran Theodor Kaufmann’s poignant “On to Liberty.”

But I was here to see the Charles Ethan Porter.

He never gave it a title, and yet this canvas, painted around 1890, is known in the art world as “Cracked Watermelon.” Instead of a rigidly formal study like the trompe l’œil favored by earlier still life artists, this melon looks like it bounced off the back of a delivery wagon and smashed on the road.

“It is very visceral,” said Yount, as we peered at the mushy flesh, fading crisp red to slimy white from exposure and rot. “Probably his most ambitious still life by this point.”

Porter was among the 19th-century Black artists — Edmonia Lewis, Henry Ossawa Tanner, May Howard Jackson, Edward Mitchell Bannister — breaking white art establishment boundaries, but unlike the others, he chose to concentrate on still life.

He became one of the first Black artists admitted to the National Academy of Design in 1869, then sailed to Paris and enrolled in L'École des Arts Décoratifs. Author Samuel Clemens (better known as Mark Twain) was a patron, and wrote letters of introduction to assist his study overseas. When Porter returned to America, he developed a following and gained respect from contemporaries like landscape artist Frederic Edwin Church. His most productive period spanned the 1880s and ’90s; he painted a lot of pretty apples and roses. And two radical watermelons.

“This was kind of his golden moment,” said Yount.

Despite this modest success, Porter’s work had fallen out of vogue by the turn of the century. Art historians blame rampant racism. More dramatic genres superseded gauzy Impressionism, and buyers became bored with Americans. At the end of his career, Charles Ethan Porter was compelled to trade paintings for food and board. He died destitute in 1923.

It would be almost another century before his watermelon landed in a canonical institution. The other, an earlier study of destroyed fruit from 1884, remains in a private collection.

“He was overlooked for so long,” said Yount. “There have been surveys of American still life painting over the last decade that didn't include him.”

We stepped closer to the canvas.

“I just love how he's created that sense of touch and texture,” said Yount. Watermelon “was considered the most challenging of all the still lives, you know, of all the kinds of fruits to paint.”

Charles Ethan Porter, Untitled (Cracked Watermelon). Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Almost immediately after the Civil War, watermelon was weaponized. With Emancipation, a more formalized type of agricultural entrepreneurship developed for Black Southerners, meaning they could finally draw income from subsistence or kitchen garden crops. But what symbolized a path to prosperity for the formerly enslaved blew up as a white supremacist trope in deeply offensive and dehumanizing songs, kitchen gadgets, toys, games, ornaments, postcards, and paintings. By the 1900s, this race shaming was inextricably woven into American popular culture.

The intentionally demeaning stereotype extended to narratives about stealing melons and eating them greedily. The first known American image of Black caricatures exhibiting “an excessive fondness” for watermelon appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper on September 11, 1869. The engraving, made by Confederate veteran and artist William Ludwell Sheppard, was captioned “A Watermelon Feast in Richmond” and showed Black children guzzling fruits. Some of the most derogatory anti-Black artifacts, coinciding with the codification of Jim Crow laws in the South, contained mocking images with bulging eyes and blood-red lips, dark skin and tattered clothing. A young boy, mouth grossly distorted by a whole melon; a little girl in pigtails picking seeds out of a melon, with the caption “He lubs me, he lubs me not.” A toothless woman wearing a headscarf, holding an absurdly elongated slice in her hands. The head of a man slowly transmuting into a melon.

The first race-shaming film debuted in 1896, a Vitascope short produced by Edison Studios, titled “Watermelon Eating Contest,” in which two Black men spit fruit at the camera. Nearly a decade later, Edwin S. Porter’s silent film “The Watermelon Patch” centered on hungry thieves being smoked out of a cabin by vigilantes with dogs. More deliberately, D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation,” released in 1915, glorified the Ku Klux Klan and villainized free Black citizens; one scene depicts a cartoonish watermelon feast celebrating Emancipation.

Ugly imagery still haunts. After Barack Obama’s election, the then-mayor of Los Alamitos, California, sent an email showing watermelons on the White House lawn with the caption: “No Easter egg hunt this year.” A syndicated cartoonist for the Boston Herald referenced watermelon-flavored toothpaste in a lampoon about an intruder in the 44th president’s bathroom. After Disney released “The Princess and the Frog” in 2009, its first animated Black princess was licensed on packaging for watermelon-flavored Dig ’n Dips candy.

Standing in the gallery with Yount and absorbed by the Porter, I nearly missed the painting on the adjacent wall. Only when I turned away did it come into focus.

“Oh my god, it's the Homer.”

Winslow Homer painted “The Watermelon Boys” in 1876. Three children — two Black, one white — in a field at the height of summer hold luscious slices. One boy lying on his stomach, bare feet carelessly kicked up, is about to take a bite. A second appears in close contemplation of his piece. And the boy in the middle, whose facial expression has the most detail, stares off into the distance.

The Met stewards some of the most important Homer works, including “The Veteran in a New Field” from his Civil War period, which also hangs in Gallery 762. Embedded with the Union army, Homer reported from the front lines for Harper’s, sketching battle and camp life scenes. His postwar studies focused on more bucolic subjects and explorations of evolving social norms. Like eating watermelon in “mixed company.”

Yount explained that the juxtaposition of Homer’s work with Porter’s invites conversation about the Black artist’s messaging during an era when he might not have been able to speak his truth freely.

“At the time the watermelon subject had become a racist trope, Porter was very intentionally bringing it back to its art historical roots as a symbol of American abundance,” she said. “It feels like a more pointed political statement in that cultural context. Reconstruction officially ended in 1877, but as we've all been reminded over the last few years, we're still living it. Legacy, legacy, legacy. Never resolved.”

I took a last good look at the Porter.

He also left one seed clinging to the rind.

Winslow Homer, The Watermelon Boys, 1876, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo: Matt Flynn © Smithsonian Institution.

“How many watermelons did Mose T paint in his lifetime?” I asked.

“Oh my goodness,” said Marcia Weber. “Probably more than a thousand? He painted them in all sorts of sizes, but he called the biggest ones Texas watermelons.”

A summer street fair had drawn crowds to the riverfront town of Wetumpka, Alabama. Curious visitors distracted Weber with questions about the work on display in her gallery, which specializes in objects by Outsider and self-taught artists such as Howard Finster, Lonnie Holley, and Jimmie Lee Sudduth. The 71-year-old gallerist had originally intended to complete her master’s in painting, but in 1981 she accepted a temporary job at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts. And then she met Moses Ernest Tolliver, who lived two blocks away, when curators asked her to help with an upcoming exhibition.

“He changed the course of my life,” she said.

Born to a family of Alabama sharecroppers around 1920, Tolliver worked as a gardener and handyman to support his family until the late ’60s, when a load of marble slipped off a forklift while he was sweeping the floor at a Montgomery furniture factory. His legs were crushed, and he spent the next couple of years battling depression and drinking heavily. Then Tolliver picked up a brush. From his bed, he covered bits of salvaged furniture, plywood scraps, or Masonite with fanciful flowers, snakes, turtles, dancing ladies, sex workers, and portraits of himself getting around on crutches. He signed his work “Mose T” with a backwards S.

“He told me a red bird was the first thing he painted,” said Weber. “And that was on cardboard.”

Tolliver would hang paintings in trees and offer them for a few dollars or in trade for snuff to anyone walking past his front porch. More people turned up after a solo show at the Montgomery museum in 1981. Around the same time, he caught the attention of guest curators at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. The 1982 exhibition, titled “Black Folk Art in America, 1930-1980,” was a watershed for such self-taught artists as Bill Traylor and Sister Gertrude Morgan. It put Mose T in the same rarified orbit.

In a review of the show, The New York Times critic John Russell called their work “uncorrupted art.” He wrote: “It was the role of Black folk art to make the unbearable bearable. When all else failed, and society had given the thumbs-down signal once and for all, art was the restorative that made it possible to go on living.”

Tolliver and his wife traveled by train to the capital and attended a reception for the show. He met Nancy Reagan. Weber said Tolliver told her that the first lady acquired two of his paintings for the private White House residence. One of them was a watermelon.

The requests started to pour in.

“Oh, you could not imagine how many letters and notes on fancy, embossed stationery arrived,” said Weber. “Most people didn't know where he lived, so they would write care of the museum, and I would go see him every afternoon on my way home.”

“So what are the characteristics of a Tolliver watermelon?” I asked.

“Well, normally red was involved, although there would be an occasional yellow watermelon, but those are pretty rare, really. It might have a black rind. I mean, didn't have to have a green rind to be OK for Mose. Often the rind and the seeds might be the same paint. He would use whatever color he had.”

Before it came down off the wall and out the front door with new owners, Weber’s last Tolliver watermelon was sandwiched between a white-haired self-portrait and a “dyna bird.” A fire-hydrant-red melon studded with black seeds, some with specks of white roughly brushed on with quick dabs. A world apart from a Peale, and yet here was the same highlighting technique.

On her desk, Weber keeps a framed snapshot of Tolliver sitting side by side with her in the bedroom that doubled as a studio, his denim jeans splattered with the house paint he favored. She admitted that it took time for her to develop an appreciation for Visionary art, but when Weber opened her own gallery in 1991, serious collectors were paying attention to this grassroots genre.

Not all of them were altruistic or fair dealing — questionable contractual arrangements between Black artists and white dealers was the subject of a segment titled “Tin Man” that originally aired on “60 Minutes” in 1993. Trusted sources are crucial for the process, especially with artists whose work is easy to counterfeit or who lack the ability to read a contract.

Self-taught artists rarely get due respect, and their work may be too quickly judged as childish, one dimensional, or deranged.

“It's been disregarded, because it has often been mistaken as an imitation of academically trained fine art,” Weber said. “Prior to 1982, it's not been recorded as historically important. So much of it has not survived.” Unfortunately, she noted, many of the artists are gone, too.

Tolliver died in 2006 after a bout with pneumonia. His “uncorrupted” paintings are in permanent collections at the Smithsonian, the High Museum in Atlanta, and the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore.

Was he intentional about reclaiming watermelon? Collector Scott Blackwell, who produced the documentary “All Rendered Truth: Folk Art in the American South,” also knew Tolliver and would visit him regularly on road trips. “We talked about how much he loved his garden and flowers,” he said. “At the end of the day, I’m sure he was well aware of the stigma and prejudice associated with watermelons, but he did sell a ton of melon paintings. and he was never one to shy away from painting what folks wanted to buy.”

Around lunchtime, I left Weber to her customers and walked across the street to a hot dog stand. The couple who’d bought the gallery’s watermelon painting sat down at the same table. They were up from Montgomery for the day. I asked if they collected folk art, and was told no, but they knew about Tolliver and wanted one of his pieces. Where would they display it?

“Our laundry room,” said the wife. “We’re going to hang it there.”

• • •

On a wide detour back to Atlanta, I followed a truck on Seedling Drive to the State Farmers Market in Cordele, Georgia. Even if the pickup wasn’t piled high with produce, the trail of fruit that smashed on the road was a clear sign that I was entering “The Watermelon Capital of the World” at the height of harvest. (Producers plant between 6,000 and 9,000 acres a year, according to the University of Georgia Extension agent for Crisp County.) Buyers pulled their cars up to the open sheds, where farmers and resellers were loading orders, passing the ripest fruit — both picnic and icebox varieties — hand-to-hand in a high arc.

Picnics are big oblong watermelons, like the one in that Egyptian tomb. Smaller and rounder, iceboxes were engineered to fit in, you guessed it, a fridge. The first seedless specimen was developed in 1939 by Hitoshi Kihara, a geneticist at Kyoto University’s Laboratory of Crop Evolution, but they really didn’t take off commercially in the States until the 1990s. Now they dominate supermarket sales, although niche varieties like the Bradford, Jubilee, Small Shining Light, and Moon and Stars appear at roadside stands and wherever melon trucks park.

“I come at 7 o’clock and leave at 6,” said Roderius “Slim” Jones, who has worked summers at the market since he was 13. He lives in Florida now but returns to Cordele and stays with his parents for the season. “I go around and toss watermelons all day.”

I chanced a burning question.

“Salt or no salt?”

“It all depends if watermelon is cold or hot,” he said. “Watermelon fresh out of the field? No salt. Watermelon cold? Salt.”

Salt draws out the sweet and cuts through the bitter. Some of my earliest memories involve a simple summer breakfast of cold watermelon sprinkled with flaky Kosher salt, which my crunchy granola mother introduced during her health food conversion in the ’70s.

“But now I like that Tajín lime salt,” Jones said. “I been eating melons all my life but only found out about that stuff this year.”

Cordele put me in mind of paintings by Black artist Winfred Rembert, who grew up not far away. One of his most compelling works about farm labor is called “Loading Watermelons” and depicts fieldhands gathering and throwing what look like Georgia Rattlesnakes into the bed of a truck parked between rows of vines.

Raised by a great-aunt in rural Cuthbert, Georgia, through the early years of the Civil Rights era, his scenes of life in the segregated Jim Crow South were autobiographical — picking cotton and harvesting melon were common themes — but so were his images of chain gangs.

• • •

Rembert was first incarcerated at 19 after attending an Americus Movement voting rights protest, which took place on the heels of the Selma marches in neighboring Alabama. When he escaped prison in 1967, sheriffs caught and lynched him. Rembert survived, but was forever haunted by the trauma of being hung upside down by his ankles as one of them threatened to emasculate him with a knife. He spent seven more years doing hard labor in the Georgia prison system, and before he was released, Rembert learned how to tool leather from another inmate. Years later, when he was 51, he started carving these narratives into large sheets of leather, using shoe polish as paint, exploring both jubilant and terrible memories. Rembert’s genre paintings of pool halls, soda shops, and juke joints in his hometown, and chain gang bosses and inmates in black-and-white prison stripes assigned to roadwork, had the complex energy and bright palette that call to mind similar scenes by social realist Jacob Lawrence.

“Stylistically, his work was about storytelling, not just a moment,” said Adam Adelson, when he invited me to view Rembert’s “Chopping Watermelon” at his family’s gallery in Manhattan. “He had a natural sense of creating compositions, but he figured out perspective on his own. And it wasn't until [later] that his wife said, ‘Winfred, you have this amazing life and no one's gonna remember it when you die. You have to tell your story on leather.’”

In “Chopping Watermelon,” workers tend to the vines in diagonal rows. Women in long dresses, men wearing black hats, all carry large hoes. The background is rust orange, like Georgia clay. Rembert wrote that he was fond of Black Diamonds, and several other of his paintings centered on eating them with family. When the Adelsons first gave him a solo exhibition in 2010, they wanted him to document his process. “We had all these pictures and we just sat him down with a notepad and he started writing descriptions of each, and some of them he put on the back of the pictures.”

Adelson shared one of these typed statements by Rembert, dated February 1998, about two scenes he painted of people eating slices on a front porch, one simply titled “Watermelon, Saturday Evening”:

“I guess I have to talk about this picture like when I was little before I knew about the stereotype. I don’t think I even knew about the stereotype until I was an adult and saw a cartoon showing a Black man caught in a big mousetrap with a watermelon used as bait. Then I understood why white folks used to drive by and stop to take pictures of us eating watermelon. Watermelon was an important part of our socializing, especially on Saturdays and Sundays during watermelon season. The melons would be so thick in the fields, they almost lay on top of each other. We’d get a bunch of them and tie them up in croaker sacks and put the sacks down in the well to cool. Then we’d sit around visiting, jumping rope, playing horseshoes and checkers, and eating watermelon. We always had a real good time.”

“Get the watermelon margarita,” said Rafael Gonzales Jr. His wife, Rozette, ordered oysters and their daughter Presley munched on tortilla chips.

On a Sunday morning in late June, El Bucanero was packed with families sharing gigantic seafood platters. Sharks, squid, and turtles floated on the wall murals; papel picado banners hung from the ceiling. Mariachis roamed from table to table.

San Antonio knows how to brunch.

We first met on social media at the beginning of “La Rona.” I followed Gonzales’ satirical pandemic series when death and disease monopolized the news because, now and then, the only healthy response is laughter. A Tejano graphic artist and self-proclaimed “piñata rope puller,” Gonzales put an image of the virus on a Lotería playing card, the Mexican version of bingo. Corona became La cabRona, a play on the word “bitch.” The traditional deck has 54 pictograms. Rafael and Rozette spent lockdown at their kitchen table putting together an updated edition that captured our collective experience — rolls of toilet paper, hand sanitizer, drive-by birthday parties, relief checks, homeschooling. La Sirena (the mermaid) became a can of tuna fish. El Sol developed a red-hot fever. An ice-cold margarita in a copper Eucharist chalice was La Coping Mechanism. The images went viral.

La Sandía has always been an essential Lotería image. It represents abundance, fertility, life and love in Hispanic culture. (One of the earliest mentions of watermelon in a Mexican cookbook dates to 1882.) Gonzales added a picnic melon sliced open on his Lotería’s El Food Bank grocery staples card. Another one of his designs featured a large glass jug of watermelon agua fresca.

“Sandía doesn't have the derogatory framings for Hispanics,” said Gonzales. “We enjoy it without the stereotypes. In modern culture, watermelon is part of our favorite Mexican snacks. Fruit cups, candies, cocktails.”

San Antonio-based graphic artist Rafael Gonzalez’s take on watermelon, including his updated Lotería, the Mexican version of bingo.

The global South has introduced marvelous ways to eat watermelon, and each culture that arrives expands the discourse: nước ép dưa hấu (Vietnamese), guazi (Chinese), subak hwachae (Korean), bateekh wi jibneh (Palestinian), tarbooz ke chilke ki sabzi (Indian), butong pakwan (Filipino), conserva di sandía (Mexican) — all here to stay.

Rafael Gonzalez, Watermelon Chile high

I asked Gonzales to point me to San Antonio’s best fruiterias, the snack stands that specialize in elaborate fruit cups drizzled with chamoy, tamarind, Tajín, pickle juice, crushed Takis. Fresh squeezed juices, horchatas, mangonadas. Paletas, in rainbow flavors. Gritty raspados Mexicanos, the acid rock cousin of shaved ice. Nieves, finer ground sno-cones. Anything cold to counter the inexorable heat crushing Texans and their power grid.

After brunch, I drove to El Farolito Refresqueria and Snacks, a lime-green building in a lot near Interstate 35, the main route heading north from the border on the Rio Grande, and one frequently traveled by migrants seeking a new life.

I ordered my new favorite, the Day-Glo watermelon raspado, a sweet-tart ice. I overheat easily and forget to hydrate on long road trips because I don’t want to constantly stop for pee breaks. But summer along the Texas-Mexico border can be deadly without water and shade, and the refreshing qualities of watermelon are nowhere more apparent than in a region suffering extended heat dome stress.

Licking fast-melting ice took down the swelter.

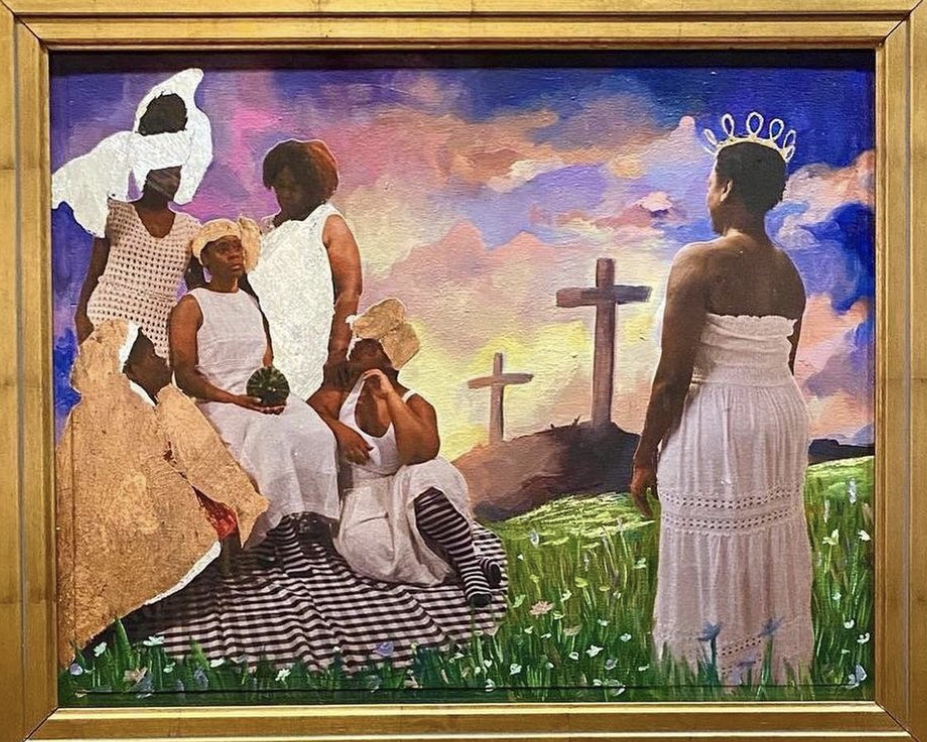

“Watermelon pops up constantly in my work,” said Atlanta-based artist Shanequa Gay. “I see watermelon as sacred, nourishing. It was carried on trips before there were water canisters. It has also long been a negative trope in the Black community alongside fried chicken. Reclamation is key to resistance of oppressed humans.”

Shanequa Gay, models for sweet sacrament divine, 2020

Gay belongs to a cadre of contemporary artists — Hank Willis Thomas, Kara Walker, Betye Saar, among others — intent on reframing identity and culture. Watermelon is a common symbol for them all.

Slices of picnic melon rest in the arms of the animist spirits Gay calls Devouts in her 2020 mural “Sweet Sacrament Divine,” and striped iceboxes appear among other symbols — cowrie shells, braided hair, black-eyed Susans — representing social protest in the 2021 installation “Her Spirit Will be Our Guide on the Way.” All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Atlanta commissioned Gay to interpret the first Station of the Cross, and she chose to render women of color as Christ and Pontius Pilate, who sits in judgment while holding a round watermelon in her lap.

“I was interested in re-contextualizing its meaning as something holy,” Gay said. “In Christianity, the Holy Spirit is characterized by water, and so for me, in my work, watermelon symbolizes holiness, histories, the feminine. When the Goddess ran things, Earth was well.”

Shanequa Gay, Carry the Wait, 2021

Shanequa gay, recovering maynard, 2021

Gay does the same for problematic portrayals of mythic figures, expressly Disney’s offensive animation of “centaurette” Sunflower, a subservient stereotype of a young Black girl that originally appeared in “Fantasia” in 1940. In 1969, the scene was edited for sensitivity, but vintage cutout books containing images of Sunflower chomping watermelon are still out there.

“I look for ways to alter this narrative,” Gay said.

The two of us stood in the Skylight Gallery at Oglethorpe University’s Museum of Art as her show “thought and memory” floated in a dreamy cosmos. This most recent work — a cobalt blue-and-black mural and paintings of shapeshifters with raven and vulture headdresses — was an exploration of sisterhood. In Gay’s personal pantheon, mythic beings — half human, half zebra — represent the power of Black community. (Those centaurettes, ennobled.) Her young girls, thought and memory, wear black-and-white striped stockings and nurture each other with Kool-Aid, piggybacks, hugs, and naps.

“I did not get to engage with my sister in that way,” she admitted.

At heart, she was celebrating rest and play.

“I look at rest as an important aspect in creativity, and we have not had any rest,” she said, alluding to the cataclysmic period of pandemic, social upheaval, racial injustice, and an assault on personal freedoms. “When is all of this gonna slow down? You know, can we come to a point of resolution or are we all gonna die while this is going on? What is the legacy of how you contribute to the chaos or fight against the chaos?”

“Nothing is tying your girls down,” I said, envious of the otherworldly frolic surrounding us.

I told her about a world championship seed-spitting contest in Texas.

Gay grinned at me.

“Now I'm trying to figure out how I can make my girls spit watermelon. That seems like a superpower to me.”

“Spitting seeds is one of my happiest childhood memories,” I said.

Shanequa Gay, Sweet Sacrament Divine, Her Spirit Will Be Our Guide, and First Station of the Cross.

In my brother Jamie’s kitchen hangs a black-and-white photograph taken at our childhood home by my father sometime in the ’60s. Jamie is seated next to our sister Kaki on a rock in the backyard. Both are naked, biting into chunks of watermelon. They were little kids at the time, messy eaters, and my mother would hose them down afterwards. It remains a treasured family moment.

“My brother told me recently about a game where his friends tried to spit seeds in each other’s open mouths,” I told Gay. “He said no one cared if they missed and caught one in the eye.”

What would summer be without juice on your chin, rinds tossed at your siblings, or seeds launched in the air?

“It is by far the best part of eating a watermelon,” said Gay. “I remember sitting on the porch of my great-grandmother and battling my cousins in spitting our seeds. The most barefoot country thing you could do. It felt like freedom.”

“Let’s go upstairs,” said Hilary. “You’ve got to see this.”

After we finished viewing Sarah Miriam Peale’s watermelon in the Fogg, I followed my sister up another flight of stairs to the Forbes Pigment Collection. It’s off-limits except to art historians and conservators, but a rotating display in cases allows everyone else to view some of the rarest colors in the archive.

Egyptian blue, once used to decorate the walls of tombs and temples. The chrome yellow of van Gogh’s sunflowers. Vantablack, a carbon nanotube-based paint as dark as a black hole. The geekiest place for two daughters of oil and turps. While neither of us really paint anymore, we remain visual thinkers, and the smell of our father’s studio lingers in our dreams.

I bent over the glass to look at a tiny jar of Mexican cochineal bugs, whose crushed bodies produce the bright carmine red color known as Crimson Lake.

The juiciest shade for watermelon.

On a blazing hot summer day in Central Texas, a town comes together to celebrate the biggest, the juicest, and the ripest watermelons around. Seeds included.

Shane Mitchell has received five James Beard Foundation awards for her stories about food and culture. “The Wounded Fruit” is the ninth installment in her Crop Cycle series for The Bitter Southerner. She can’t paint a lick, but words will do just as well.

More from the Crop Cycle Series