James Brown Live!

/Berkeley, California

By Gary Bland

I was 15 in the summer of 1963, between my sophomore and junior years in high school, when I got my first adult job: part-time work at a discount shoe store on Hull Street, a low-rent district on the Southside of Richmond, Virginia.

On those few blocks, businesses were segregated, with black shops on one side, white on the other. With the summer heat, the glass double doors of the shoe store were propped open, and I could listen to music from the black-owned record store across the street. They played the latest rhythm and blues releases through a set of speakers on the sidewalk.

I loved hearing that music, and many times I would run across the street to ask who the artist was. By that time, Chuck Berry had created rock and roll, and Ray Charles and Jackie Wilson had several crossover hits played on white radio stations. But this was a whole new world of black artists for me. The Miracles, Mary Wells, and Johnnie Taylor. “Any Day Now” by Chuck Jackson was a hit played frequently. I loved that song and remembered, as the song faded away, how his plaintive plea would soar above the busy city street, “Don’t fly away, my beautiful bird.”

In my junior year of high school, the British Invasion was still a year in the future, and the music on the pop radio station seemed limp and tepid in comparison. Several years earlier, we had moved to a new home on the outskirts of town, one of many developments going up with two- or three-bedroom brick homes on designated lots, meant to allow working people to buy their own homes. And with a short walk to the highway, I could catch a bus into Richmond to exercise my growing independence.

At that point in our lives, my older brother and I were becoming like the two characters in the old movie, “Angels With Dirty Faces,” where one grows up to be a gangster and the other a priest. My brother was the bad boy — trouble in school, minor brushes with the law, and the harsh discipline of my father’s belt. He still carried marks on his bare buttocks from some transgression a year previous. I, in contrast, was the good boy. I wanted to be a minister and was president of my church’s youth group.

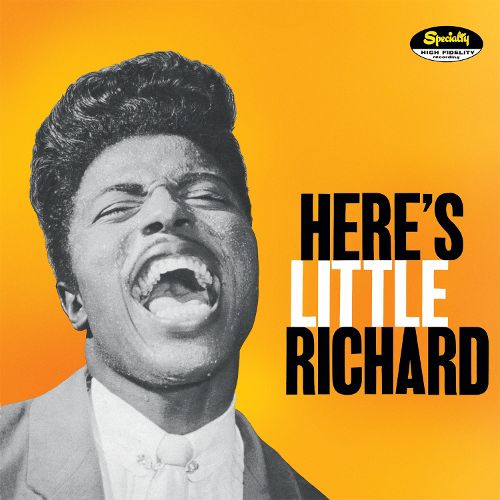

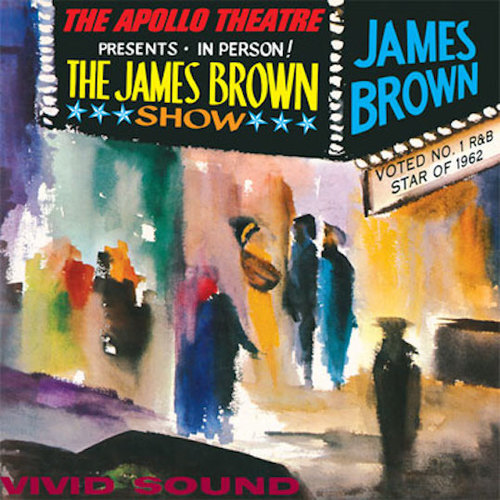

One day, my brother came home and shut the door to our bedroom, where I was playing records, and gave me three albums. They were brand new and still sealed: “Here’s Little Richard” (1957), “Go Bo Diddley” (1959), and “Live at the Apollo” (1963) by James Brown. I knew he didn’t have money to buy three new albums, and asked incredulously, “Did you steal these?” He abruptly looked at the closed bedroom door, ensured no ears were listening on the other side, then gave me a sly smile before leaving.

I played those albums incessantly. Listening to Little Richard was like jumping onto the back of a tiger. His vocals were so impassioned you could hear him gasp for breath between lyrics. Bo Diddley introduced me to Caribbean rhythms, and his resonant baritone voice yearned for love or moaned like a restless spirit in some dark, swampy graveyard.

But it was James Brown’s “Live at the Apollo” that started the fire. I had never heard anything like it, from the opening emcee’s exhortation to the audience, “Lets everybody shout and shimmy!” to the extraordinary mesh of Brown’s voice with his audience. When he broke into the opening lines of “Please, Please, Please,” the audience sounded like they were on the first big dip of a roller coaster. It made my hackles stand up in a strange way.

The album cover itself was a wonder to me. Unlike most album covers, with slick, colorful portraits of the artist, this looked like the cover of a jazz album. It captured the outside of the Apollo Theater at night, 125th Street lit by the brilliant marquee advertising James Brown’s appearance. Wraith-like figures, drawn to the light, gathered under the bright colors. Sometimes, while playing the album, I would imagine myself standing under that marquee with my ear pressed to the crack in the entry door, listening.

The following summer, I got a job at the state warehouse in Richmond, grunt work loading and unloading pallets. Since this was a full-time summer job, I was awash in money. I was grudgingly trying to save for my as-yet unplanned college endeavor, but I loved the freedom of buying a record or going to a movie without having to ask my parents for money. I was reading the paper one morning when I saw an ad for a James Brown concert coming to the Mosque Theater in downtown Richmond the next month.

This was my chance; I had to go. I knew I could afford a ticket, but I didn’t want to risk asking my parents for permission. Coincidentally, the Richmond Braves, Richmond’s minor league baseball team, were playing the same night of the concert. I had already taken the bus in for night games, so I knew I could go into town without raising suspicion.

As the days passed, however, I began having second thoughts. I had already seen the consequences my brother had suffered for lying. And this was still the old, Jim Crow South, though there we were starting to see some signs of change. At that point in my life, I was fortunate to have a minister at our Methodist church who was outspoken and supportive of the civil-rights demonstrations throughout the South. I sang in the choir and got a secret pleasure watching the congregation squirm uncomfortably, as he implored his flock to love blindly and support our brothers and sisters, no matter their color.

Personally, he talked to me as an adult, and we had conversations about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., racism, segregation, and what a Christian’s response should be. It felt strange, living in this segregated world — where I could see, but never speak to, black people. I suggested to the minister that we plan an event, where our Methodist Youth Foundation group could have fellowship with an MYF from a black church. He said he knew some black Methodist preachers from his district meeting and would speak with them to set something up.

When the night arrived, only six of the 12 members of my youth group loaded into cars to take us to a black Methodist church near downtown Richmond for our fellowship. Here, we met their MYF, teenagers like us. We were all dressed in our Sunday best and were greeted with small sandwiches and snacks. Punch was served from a glass bowl. I talked with William, the president of their group, and we tentatively explored objects of conversation we might have in common. It was rather awkward and polite, and I may even have bent my pinkie while sipping from my cut-glass cup. Things seemed to loosen up as we played some parlor games, and we had fun.

Before we left, I invited William and his group to our church for fellowship the following month. The next day, I called my pastor and excitedly told him of the event, how it started out awkward, but became more warm and friendly, and that I had invited them to our church the following month. He was pleased and, over the phone, we said a prayer of gratitude.

The following Wednesday night, the reverend came to visit me. It was after 9 p.m., an unusual time for a visit. I could hear my parents in the next room watching TV as we sat down in the living room. He told me he had just come from a church board meeting. He avoided my eyes as he explained the church board had voted not to allow the black MYF in our church for fellowship. He was sad and disheartened, but had to abide by the board’s decision.

“But what about William? What do I tell him?” I asked.

He said he would talk to their pastor and explain the situation. I knew I was too ashamed and embarrassed to make that call. Before he left, he offered up a word to God, probably asking for wisdom and understanding when others fell short of His expectations, but I couldn’t hear the words of his prayer.

I just heard the roaring in my ears. This was the first domino to fall in a series of lessons and disenchantments with the church, and only fueled the desire to seek my own knowledge.

At that time, the Richmond Braves had recently hired their first black player, and I went one night to see him play. I was seated in the stands waiting for the game to begin when a group of black people, five children and three adults, entered and began their way down the row to be seated. Every public event I had ever experienced had been with an audience of white people — something I had taken for granted but never deeply considered. So, I got this rush of goodwill and thought maybe things were changing.

After the small group was seated, one of the men stood and began making his way back down the row, probably making a concession run. A loud voice from several rows behind me rang out over the crowd: “Keep walking, n*****!”

It was like a sucker punch to my gut and my naive reverie of progress. I jerked my head around and saw three young men, two rows up. The two on the outside were giggling, the middle one was smiling, rolling his tongue around in his mouth like a piece of hard candy.

Even now, I am left with the same thought: I hope those children didn’t hear that. If the situation were reversed, if I were the only white face in a sea of dark faces, couldn’t I, at the least, expect the same treatment?

But neither the threat of my father’s belt nor public humiliation could cool the hot desire that had grown in me. On a weekday afternoon, I got home from work, showered all the warehouse dirt and grit off me, ate a quick snack, and, wearing a fresh flattop haircut and my best checkered shirt, caught the bus into Richmond.

I was excited about the Mosque, as well. It was the grandest theater I had ever seen. I had been there only twice before, once to a Peter, Paul, and Mary concert, and once to a “Teens for Christ” rally, where only the first three rows of the enormous space were filled. I got off the bus and walked up the block, where throngs of people swarmed into the building. Tickets were almost sold out by the time I got to the box office, and I got a seat in the next-to-last row of the balcony, which was perfect, since I was trying to be invisible. I had a plan when I entered the lobby: Stick to the perimeter, walk along the wall, slowly but purposefully, and keep my eyes straight ahead. It was my attempt to keep my solitary white presence as unobtrusive as possible. But I found myself tripping over my feet as I craned my head around at the festive crowd. With the hot weather, there were bare arms and shoulders, and bright colors. There was an excited, anticipatory mood. The collective greetings and conversation made a din in the vaulted lobby.

As I approached the stairs to the mezzanine, I noticed four young men, talking in a circle. To my surprise, one of them was white, the only other Caucasian I saw that night. All had haircuts like my brother, combed back slick on the sides, with the top rolling forward and cresting down over the middle of their foreheads. Their clothes were almost identical — long-waisted sport coats of a shiny material, black, peg-legged pants, and pointy black shoes. The white one noticed me, too, and, for a brief, odd second, our blue eyes met across the lobby before I turned to ascend the stairs. On the mezzanine level lobby, there was a counter filled with cups of Coke, filled to the brim, no ice. I laid my coin on the counter, grabbed my Coke, and took the stairs further to the balcony. There were several empty seats in these last few rows, and I settled into mine. I breathed a small sigh of relief as I looked around. I had made it without incident or being noticed.

And then, the couple directly in front of me looked back over their shoulders and grinned. I had been spotted.

“Looks like we got a James Brown fan here tonight,” the man said.

I told them this was my first time seeing him and that I had become a big fan after listening to “Live at the Apollo.” They had each seen James Brown several times before, and as we talked, I got the impression this was their first date. She looked up at me from beneath heavy-lidded, Cleopatra eyes. Her lips were the colors of frost and peach, and she wore large, gold-hooped earrings that brushed her bare shoulders. He was Chuck Berry’s “Brown-Eyed Handsome Man.” His hair swooped and crested in a shiny wave. A thin, carefully trimmed mustache ran along the edge of his lip.

His date looked directly at me and said, “Of course, this is the first time I’ve seen James Brown from up here in these cheap seats,” and gave her partner a pouty smile. He threw back his head and laughed and then wrapped his long arm around her, squeezing her to him like she was something precious. Just before the lights dimmed for star time, he turned around to me and brought something out of his jacket. My Coke was about two thirds full by then, and he topped it off with amber liquor from his silver flask. He said, “Enjoy James Brown, brother.”

I couldn’t believe it was the same emcee who had introduced James Brown on the record, repeating the exact litany, which I had memorized by that time. The mysteries of “shout and shimmy” were about to be revealed. When James Brown entered the stage in a bright red suit, the audience rose to its feet and remained throughout. I don’t remember an exact song list from that night. But I know he did all the hits: “Try Me,” “Please, Please, Please,” and “Prisoner of Love.” I had always liked “Night Train,” where he called out cities on the train’s route. I had heard different places like New York City, Chicago, and California mentioned in songs, but that night, he yelled out destinations I was familiar with, like Atlanta, Georgia, and Raleigh, North Carolina. Of course, we all screamed out when he shouted, “Richmond, Virginia.” He was the consummate performer, more preacher than showman as he progressed, exhorting the audience like a congregation of believers, his urgent, tumultuous testament reaching even the back rows of the balcony.

He was singing a song I was familiar with, that I had heard on the radio, but something was happening. It had extended beyond the two-and-a-half minutes I had expected and kept expanding, and with his two drummers flailing in unison. The swaying shadows of the crowd seemed to grow longer. Something was happening.

His brass section — the saxophones and trumpets — began rocking their horns back and forth in military precision, the reflective spotlights sending laser spots of silver and gold racing around the great walls and swaying throng. Cigarette smoke from the audience had risen and dissipated, catching smudges of light in midair. Slick with sweat, Brown seemed to struggle against great odds to reach the microphone to shout out to the believers, only to be pulled back, as if some great, invisible hand had grabbed the back of his jacket, yanked him backwards, almost off his feet, and sent him spinning.

From my seat at the back of the balcony, the radio format in my head was blown. I was staring down into a whirling miasma of rhythm and light, someplace unexpected, someplace strange, sensual, and wild, and I was holding onto my seat like an anchor. And the voice of James Brown spoke to me.

“LET GO! LET GO! HERE, TAKE MY HAND! I GOT THIS.”

I felt the unfamiliar sensation of my nipples growing hard beneath my shirt. The top of my head, the bone itself, was missing, replaced by a rush of cool, electrical air. Although my feet were firmly planted on the floor, I had the sensation the entire building, the great Mosque, had broken apart from its foundation and was floating above the ground. The interior walls and angles seemed to lose their certainty, and moved and pulsed along with the elongated figures of the audience. Flitting, staccato bursts of silver and gold tricked my vision, and I was part of this, of a wave of bending circles and rhythms, where, at its center, in a spotlight, James Brown danced in a red suit.

After the concert, when we came out of the doors and into the night, we were all floating just above the ground. There was this feeling of shared wonderment and gratitude in the crowd. Any notions I had had about being white in this crowd of black folks were blissfully erased.

It was my first of those rare experiences when music becomes magical and somehow changes you.

I moved along with the crowd toward Franklyn Street, where I would catch my bus, but when I got there, a logical but odd thing happened. While the large crowd gathered at Franklyn to catch their bus back to Church Hill, Richmond’s main black district, I crossed to the opposite side of the street to catch my bus back to Richmond’s south side, the white part of town. As I stood alone at the darkened bus stop, I watched as a line of city buses pulled up and loaded passengers on the other side. The interior lights of the bus were bright, and happy concert goers filled all the seats, and then jostled in place to fill the aisle, grabbing on to something or someone as the packed bus lurched forward and another bus pulled up to load.

I envied them, all those passengers, because tomorrow they would be greeting their neighbors and friends on the street, at the post office and market, with: “Did you see James Brown last night?”

After the fourth bus loaded up, mine finally arrived. The driver gave me a smile as I entered. The bus was empty, so I had it all to myself. All the windows were down, and I made my way toward the back and took a seat on the right side to view the passing night scenery. I went over who I knew, trying to think of someone I could share the night’s experience with. A few friends from school? Maybe my best friend down the street? But when I pictured their faces looking back at me, quizzical, uncomprehending, I felt protective of my experience. Perhaps I could tell my brother of my transformative transgression, if I could get his attention long enough.

Driving out of Richmond, we passed through an old, upscale neighborhood, some houses with the traditional colonnades of the Old South, their long lawns lit for display. Then the beautifully manicured Country Club golf course, where the wealthy played. The rain birds had left a reflective glow over the lush, rolling course. When the bus crossed the Huguenot Bridge, I felt the temperature drop a degree, and I could smell the muddy water of the James River, and then we were heading toward the planned neighborhoods and developments.

It was getting late for a weeknight, and most of the houses were dark. As we passed a house that backed up to the road, I could see a flickering blue light from a bedroom window, someone watching Johnny Carson. We came to a stretch of woods, the last remaining undeveloped section of the road before my stop. There was a thick, simmering humidity, and the old forest was a pallet of darkness. I reminded myself to check the baseball score the first thing in the morning, so I could cover my story.

Soon, I would be back home, safe and sound, but I was left with a strange feeling as the evening’s music still played in my head. I had been a guest at tonight’s concert, but I felt a similar detachment as I watched the familiar nighttime scenery pass. I was an interloper here, too, and was struck by some aphasic sense that I would go on to view much of this world from the outside, looking in.

The moving bus blurred the sound of crickets, and there was a bite of exhaust in the draft through my window, mixed with the smell of ripe, roadside honeysuckle.