The Music Lover’s Town Square

/By Derek Sweatman

Atlanta, Georgia

It’s like a needle in the cartridge

When the record spins

I like diggin’ down deep

In the record bins

— Beastie Boys, "Super Disco Breakin’"

In the bottom of an apartment building near our home in Atlanta, there’s a record store. It’s been around since the 1970s, run by two audiophiles who have amassed quite a collection of vinyl. They know me and my son. We’re regular diggers.

Atlanta has had its share of these old shops, several of which are still around.

- Wax-N-Facts

- Criminal Records

- Fantasyland Records

- Wuxtry (based in Athens, but with an Atlanta location)

- Decatur CD & Vinyl

Locally owned, small, and novel, these are the only vinyl shops left. They survive on things like nostalgia, their unique collections, and how well-versed they are in what they sell, a type of internal Genius Bar factor. Times have changed. The music they have may be vintage, but these holdouts now come stocked with email lists, Facebook pages, websites, and debit machines. They’ve upgraded. Same old dog, new tricks.

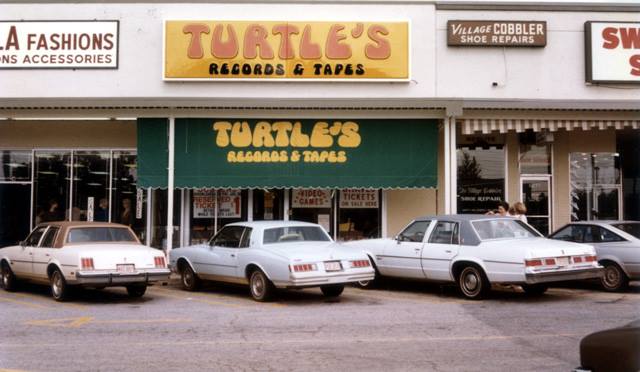

When Prince died, I pulled “Purple Rain” off the shelf to play for the evening. And right there on the plastic wrap was the Turtle’s Records & Tapes price tag, still intact, like new. I touched it, stared at it, and showed it my son, an unexpected scene of reminiscence. During my high school days of the late 1980s, Turtle’s Records & Tapes was the local chain. There was one near our home in Decatur, near Northlake Mall, on Henderson Mill Road. It’s gone now. Every Turtle’s is gone. But I still think about that place, and about the afternoons I spent there with my friends, rummaging through pine boxes filled with music.

My memories of that store are mainly shadows and moods, these old still-frames of the years I spent in those aisles between tables of pine and wax. The whole historical experience is not retrievable. I never went to Turtle’s to construct a story to tell. I went for the music and the concert tickets and to be with my friends. I went because I had cash in my pocket and records I wanted to buy.

But there are things I still see.

I still see the colors, the yellow and green and orange that covered the walls, the bags, and the sign out front. I see many people, though hardly anyone in particular. By its nature, the record store, any record store, was a town square for people who loved music. It was a shared space for many genres, like stalls at an indoor market. There were sections for certain styles and new releases, but generally, it was mapped out by the alphabet. If you wanted the Beach Boys, you went to the “B” box. If you wanted the Beastie Boys, same box.

Weird, isn’t it? A buying experience not based in algorithmic data. It forced interaction with music you didn’t like, and it made you lean over the shoulders of people you would otherwise never speak to, and ask if they’d grab that copy of the J. Geils Band for you. And it was the 1980s. Could you name another decade when every genre had a shot? From Run-DMC to Rush, every type of music had its stadium-filling stars, and Turtle’s sold them all. It’s an image I still carry.

I can still see the day when I got up before dawn to stand in line with my friends to buy U2 tickets for the Joshua Tree Tour of ’87. It was a school day, and I was elated my parents let me miss first period to spend money on a show. In those days, each record store got its own allotment of tickets for upcoming shows. They could run out of tickets before you made it to the counter. Standing in line wasn’t a guarantee, it was a risk, an act of faith.

Everyone was anxious over the prospect of a morning ill-spent, and the fear of having to chase down a ticket elsewhere. It was slow, too. Once you were inside, you would look over a seating chart (of Atlanta’s now replaced arena, The Omni) and choose your tickets based on location and price. The tired employee who drew the short straw for that day would take your cash and give you your tickets. I still see that, that scene of walking out of the store, relieved that I had a seat, holding it in front of me and staring at it, unable to post a picture of it online because ... well … there was no such thing as “online.”

I can still see the little yellow booklets where we collected Turtle’s stamps. Fill the book with stamps, get a deal on your next purchase. An Atlanta-area stocking stuffer.

I can still see the art. Part of the rummaging was art appreciation, picking up those 12-by-12 sleeves covered in images or drawings or photos from live shows. Just to stand there and hold the record — turning it over many times, reading the track list, and asking a stranger, “Have you heard this one before?” — was all part of the tactile experience. This was not unique to Turtle’s, but Turtle’s was what I knew.

I drove by there the other day. The only thing I recognized was the Blue-Ribbon Grill across the street. Most everything else is gone or has changed hands. That’s how it goes. Decrease and increase. But every time my son and I go to the record store around the corner, I look for that round yellow sticker on the sleeve. Who knows? Maybe I’ve held it before.

Keep digging.