Chasing the Goose

/By Susan Rebecca White

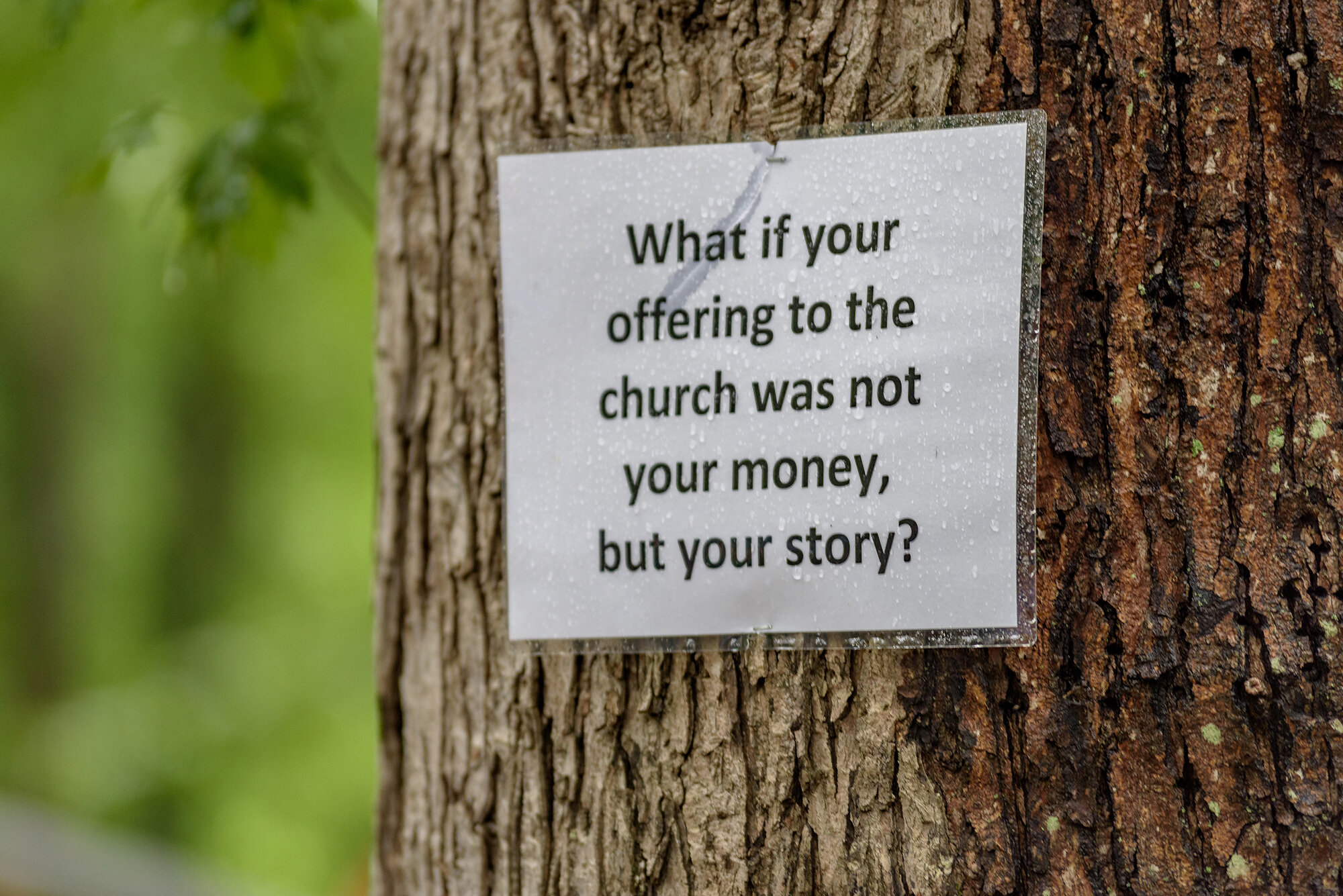

Expansive tents dot the campground at the Hot Springs Resort and Spa in Hot Springs, NC, sheltering conversations, workshops and performances for the many sessions offered during the Wild Goose Festival held every July in Hot Springs, NC. Photo by E. lane Gresham

“When the forces of extremism become so overwhelming that they depress the hope of the people, the prophetic voice and mission is to connect words and actions in ways that build restorative hope, so a Movement for restorative justice can arise.”

— the Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II

I have been certain of the existence of God exactly three times in my life, hearing the whisper of a voice not my own that I knew was folly to ignore. This “still, small voice” urged me to leave my dysfunctional marriage, promised a true partner to come (soon after, I met my now husband, Sam), and insisted that I visit with detained immigrants warehoused at Stewart Detention Center in the remote town of Lumpkin, Georgia.

That’s three moments of certainty in 44 years — three moments of what I perceived to be direct messaging. Whereas the bulk of my life of faith can be best described as just that: faith, which, as Anne Lamott likes to say, is the opposite of certainty. It is my faith that compels me to live as if the promise of the gospel is true: that love is ultimately a stronger force than death, that the last shall be first, that reconciliation will one day come, with God and humanity working in concert to bring about the beloved community.

I am thinking of all of this during the last leg of my drive to Hot Springs, North Carolina, where the Wild Goose Festival is being held. (I am also listening to Lizzo’s new album, “Cuz I Love You,” and dancing in my seat in such a manner that would most definitely embarrass my child, and, well, pretty much anyone else who saw me.) How fitting that this final stretch of mountain road so accurately seems to represent my spiritual journey: winding and marked with only occasional signage. Cell service, including navigational help from Google, cuts off about 30 minutes before I’m supposed to arrive, so that I’m operating on faith that I’m even headed in the right direction.

When I spoke with the Episcopal priest and memoirist, Barbara Brown Taylor, she compared the Wild Goose Festival to the pilgrimages of yore: It’s not a replacement for one’s home church, but rather a holy site one travels to for inspiration and rejuvenation, especially if one’s faith has grown distant or rote. The Hot Springs location is certainly inspiring, a hamlet tucked within the mountains of western North Carolina where, for three nights, progressive Christians commune with each other, setting up campsites along the French Broad River so that any time they get too hot or too muddy they can dip their feet — or their whole body if so inclined — in the cold, refreshing water. (A friend did warn me, as we began our wade, that the French Broad has tested particularly high for E. coli, thus muddling the pure baptismal waters of my imagination.)

Highlights of this year’s program included talks and panels featuring Rev. William Barber II, Dr. Jacqui Lewis, Barbara Brown Taylor, Nadia Bolz Weber, John Pavlovitz, and, yes, the sometimes wise, sometimes maddening Marianne Williamson. Musicians played throughout, including a raucous and engaging performance by the Collection, a frenetic seven-member band out of Greensboro, North Carolina. In an interview on the blog “Spirit You All,” lead singer David Wimbish spoke of losing his faith, or maybe just his conservatism, after he grew to love several friends who were gay and found himself questioning how a God of love could not fully love them, too.

Many of the people I spoke with at the festival told me that they once professed fixed, dogmatic beliefs. And then some sort of a “good crisis” intervened, making the box in which their faith resided too small, so that, as Barbara Brown Taylor puts it, they had to add some windows and a door. Like the mother I met who was active in her Southern Baptist church before her son came out, and she had to choose between him and a conservative theological doctrine. Or like the woman who left her hip, evangelical church after Donald Trump’s 2016 election, when the pastor offered nothing more than tepid “prayers for all people” in response.

Or like that same friend who waded into the French Broad River with me, who left her more orthodox church around the time of her fortieth birthday, when she began to recognize that as an unmarried woman, she was being pushed to the margins of church life, the center reserved for straight married couples with children. She told me the “good crisis” that led her to a more open faith also led her to ask how much of her Christian beliefs had been shaped by her whiteness, by deeply ingrained notions of racial superiority that so many white people are subtly (or not so subtly) taught to believe.

Questioning one’s cultural biases is humbling. It also tends to lead to faith-based activism, which is at the heart of the festival, at least during this peculiar historical moment, in which conservative, white evangelicals provide a bedrock of support for the flagrantly immoral Donald Trump, making those of us who also claim Christ desperate to live in such a way that refutes a theology of cheap grace, brutal patriarchy, and white supremacy.

The majority of Wild Goose attendees are white — a fact that escapes neither notice nor comment. This is a group that does not shy away from talk of systemic racism and white privilege. Indeed, dismantling structural racism was at the root of many of the festival’s calls to action — whether it was combatting climate change, or putting an end to the death penalty, the industrial prison complex, and the child separation policy at the border, all of which disproportionately (and, I would argue, purposefully) affect people of color.

There was one lonely woman in a “pro-life” booth. I never observed anyone approach her. More common were shirts reading “Trust Women.” One woman wore a pale pink T-shirt that read, “God Came Into the World Through a Vulva.” A writer, she told me that the previous week she had been excommunicated from her church, the Anglican Church of America, for blogging her support of things they did not condone, including full inclusion for gay Christians and the ordination of women.

The issues grappled with at the festival are heavy, but there’s a concurrent goofiness to the whole thing. Such as the nightly “silent disco,” during which participants all dance to the same music, only piped in through earbuds, so a casual passerby might wonder if this group of quiet, undulating souls has been possessed by some groovy, supernatural power that really digs gender non-conformity. The queerness of the festival cannot be understated: boys in dresses, boys in rompers, boys in midriff-bearing shirts, queer girls, bi girls, non-binary folks who identified neither as “he” nor “she,” but “they.” Rainbow flags everywhere, Midwestern-looking mamas wearing shirts that read, “Free Hugs,” along with buttons identifying them as “Mama Bears.” Even before I sat down to talk with these fierce, loving women, I knew that they had chosen their kids over doctrine.

Ostensibly, I went to the Wild Goose Festival so I could write about it for The Bitter Southerner, but I had other reasons for journeying there. It wasn’t that I needed to escape any sort of damaging theological indoctrination from my youth. I had been raised in a progressive, mainline Protestant church and had joined a similar congregation as an adult. It was that I was in the middle of a sort of general malaise, a nagging feeling that, though I was surely on the right path — after all, I loved my husband, my son, my church, my writing career — middle age was not presenting as I had once hoped it would. Over the past few years, two of my close friends have died, one from suicide. Two other friends have received sobering medical diagnoses of Parkinson’s Disease and breast cancer, respectively. And then there was the more quotidian midlife phenomenon of watching friends’ marriages end, with spouses looking at each other after years in the trenches of childrearing and career building and not knowing who the hell the other one was.

My own marriage was strong, but financial security continued to elude us, each of us having chosen a career that is fulfilling but doesn’t necessarily fill our wallets. I write this cognizant of how buffered by privilege we are — I am — and how the slightest shift in my own perspective can always help me realize just how stable the ground beneath me really is. It was only a few months ago when a woman from Madagascar came to my small home for tea. As I showed her around, I pointed to the single bathroom that my husband, son, and I all share, casually announcing, “We make do.” Later, she mentioned that one of the things she was enjoying most about her time in the United States was consistently having running water.

Here’s the thing: Even after this humbling exchange, I quickly returned to my default position of wanting more. More space, more luxury, more money.

But I also wanted to figure out how to be more explicitly Christian in the world, how to start defining my faith by what it is rather than what it isn’t. I joke that I should begin every essay I write on faith with the following disclaimer: “I’m a Christian, but I am not anti-gay, anti-Muslim, anti-Semitic, anti-gun control, anti-choice, or politically conservative.” But something is lost in the preamble — notably, what it is that I do believe in.

And then, there was this: I was exhausted. Back in 2017, I resisted the policies of the Trump administration with energy and zeal. I joined an Indivisible Group. I called my senators several times a week and schlepped to their Atlanta offices to urge them, first, to vote against Betsy DeVos’s confirmation, and later Brett Kavanaugh’s. I went to the state capitol to speak out against the “campus carry” act that would allow students at public colleges and universities in Georgia to bring their guns to class. I spent four Sunday afternoons canvassing for Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams and spent several weeknights cold-calling strangers to see if they knew where their polling place was and if they might need a ride on election day.

Time passed, and the grinding cruelty of the administration continued. At some point during all of this, it was revealed that babies and toddlers were being taken from their parents at the border and locked up in separate facilities, one of which infamously deprived their tiny prisoners of soap and toothpaste. For nights after I was first made aware of this policy, I lay awake in bed thinking of children younger than my own beloved 5-year-old son warehoused in detention centers, under the guard of Border Patrol agents who knew nothing about caring for traumatized children, let alone their language, their culture, or even the foods they normally ate. I thought about how often children sleep with their parents and how grief-stricken these children must be, sleeping on cots or the floor, with no warm parental body nearby, no reassuring heartbeat, no guarantee of when or if they might see their parents again.

Had my activism made any difference? Possibly not. But what was the alternative? I had just finished writing a novel that was, in part, about radicals in the 1960s and ’70s intent on bringing down the United States government to rebuild a more just and equitable community. Spoiler alert: Their plan didn’t work. Innocent people were killed, and minimum-wage workers cleaned up the rubble from their bombs.

When Trump was first elected and I was overcome with grief and fear, I texted a friend who was similarly distressed. One of the things we discussed was that joy was prophetic. To look with open eyes at the broken world around us and still find beauty and joy was to live in the promise of God’s beloved community to come, was to see the kingdom of God breaking through. We told ourselves we would look for joy, even in such a time as this. But it had been nearly three years since I had made that commitment, and malaise had taken root.

Where to find joy in this dismal landscape?

I got a taste of it at the festival’s “Beer and Hymns.” This event recurs at various times throughout Wild Goose, but the most raucous gatherings came each night at 11 p.m. under a big, white tent with chandeliers hung from the ceiling. A group of musicians gathered in the tent’s center, brandishing guitars, drums, tambourines, and a flute, while others passed out stapled-together hymnals. Flipping through her hymnal, I heard one young woman, her dark hair shaved in the back and long in the front, remark, “I recognize most of these Baptist bangers.” Later, when I played a few clips for BS editor, Chuck Reece, he could identify all of the songs because of his parents’ involvement in gospel quartets: “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms,” “I Saw the Light,” “Soon and Very Soon,” and many more.

Which is all to say, the hymns were unabashedly Jesus-y, and people were into them: hands thrown in the air, beer mugs swaying, musicians beating hard on their guitars as we belted out, “Praise the Lord, I saw the light!” Gay boys, lesbians, trans kids, and their super-supportive parents were singing — we were all singing — and we were harmonizing, and it was fun and campy, and we all knew it was campy, but it was also moving, all of our voices lifted together, taking back the hymns that had been denied to so many of us because of sexual orientation, or critical thinking, or promiscuity, or any number of things used by those in power to try and keep people from God.

Singing my heart out, I felt that we might drive back the nihilistic forces that are currently in charge of so much of our country. Singing, I felt that the spirit of God was real, present, and with us. I understood, for the first time ever, the lure of modern, conservative evangelical culture, with its stage lights, rock bands, unfettered enthusiasm, and cute, Christ-loving boys. We had the lights, the music, the enthusiasm, and the cute (gay) boys, but not the brutal theology that divides the world into “us” and “them” and then declares the “them” destined for everlasting hell.

Which brings me back to the question of my theology, of exactly what it is I believe in. My understanding of Christianity is that it is not a matter of individual salvation in the sense of divvying up of the “saved” and the “damned,” but rather a call to love our neighbor — our Jewish neighbor, our Muslim neighbor, our atheist neighbor, our immigrant neighbor, our gay neighbor — understanding that God’s will is the reconciliation of all of humanity, someday, somehow. It seems to me the point of Christianity is wholeness, being fully human and integrated. Not repressing the parts of yourself you or others are uncomfortable with, but bringing those parts into the light. It seems to me that the point of Christianity is discernment — becoming aware of our deep capacity for sin, by which I do not necessarily mean, say, premarital sex, but rather the blindness of one’s own advantages as a result of systems of supremacy, the worship of guns, the worship of domination and power and money and acquisition. It seems to me the point of Christianity is understanding we are made in God’s image, and while my human mind can only comprehend the shimmering edges of God, I know that God is love, and I know that God is creative.

I sang as loud as I could. I couldn’t stop smiling. And I understood that when I left this holy site, I would be refreshed, ready to continue the long, slow slog of fighting for justice, all the while remaining alert for moments of joy to break through, proof enough of God’s presence.

Susan Rebecca White is the author of four novels: Bound South, A Soft Place to Land, A Place at the Table, and We Are All Good People Here. A graduate of Brown University and the Master’s in Fine Arts program at Hollins University, Susan has taught creative writing at Hollins, Emory University, the Savannah College of Art & Design, and Mercer University, where she was the Ferrol A. Sams, Jr. Distinguished Chair of English Writer-in-Residence. An Atlanta native, Susan lives in Atlanta with her husband and son.