Our Man in Biloxi

/Dispatches Past and Future From the Mississippi Coast

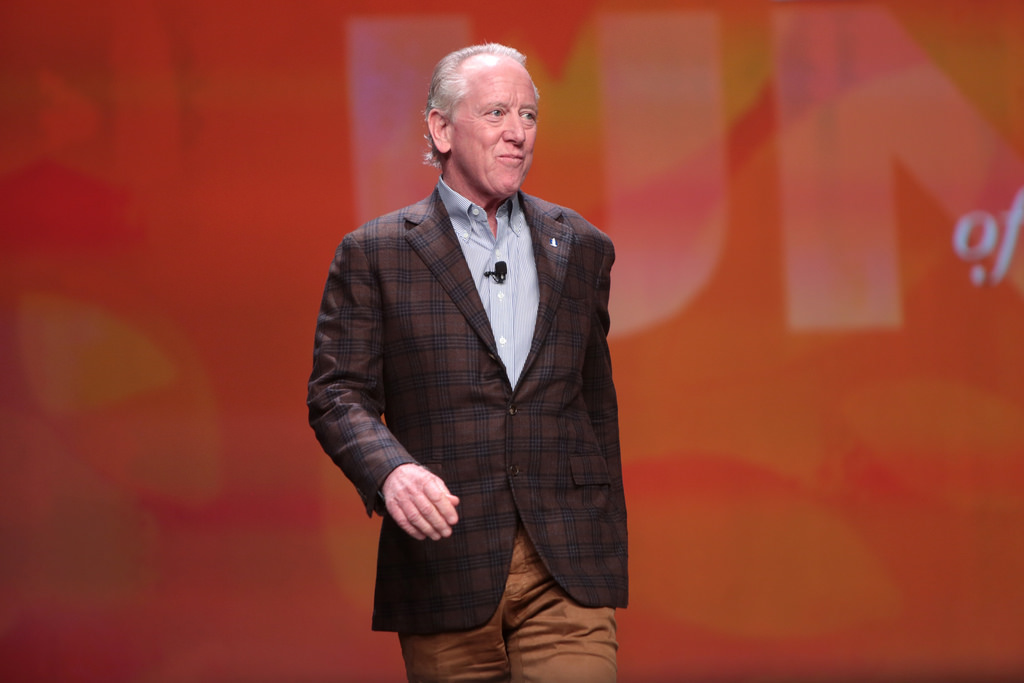

Archie Manning

By Tom Lee

Late July, Gulfport. It has been raining for hours when I arrive for the Southern Legislative Conference. The airport doors slide open, and rainforest-strength humidity coats my glasses in a thick fog.

As they clear, I meet our shuttle driver. She speeds through a landscape of green and steel gray. She came here a child of Vietnamese refugees, fishing people who found sanctuary from war in the climate and seafood industry of the Mississippi coast. She now works for the people of Mississippi, inspecting seafood producers. She is one of 7,000 people of Vietnamese descent living in Mississippi.

It is 2017, not 1977, but it will not be the last time this week I am reminded of the past.

~~~

Mike Strain, the bull-necked Cajun agriculture commissioner of Louisiana, is holding forth before the conference's agriculture committee the next day. He is a Republican, proud of his four trips to the White House since Donald Trump's election and his candid advice to a new administration suspicious of America's trade deals.

"You know who elected you, right?" He points at the 35 legislators around the committee roundtable. "Rural America. Rural America depends on trade."

His topic is Cuba, and the dollars Southern farmers are leaving on the table by their inability to sell corn, soybeans, and beef to a hungry neighbor 90 miles from Key West. He says the island nation of 11 million people imports 80 percent of its food. Meanwhile, Louisiana farmers export nearly two-thirds of their annual production.

To Strain, it is an agricultural marriage that ought be made in Baton Rouge and Havana.

"We trade with North Vietnam. We trade with the People's Republic of China. We trade with Russia. We ought to trade with Cuba."

No legislator takes up Strain's call. In fact, questioning Strain's economic enthusiasm, one state senator brings up the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Of 1962.

~~~

But forget all that. The keynote speaker is Archie Manning!

College football is the South's civil religion, and Archie Manning is its high priest, the one who intercedes on our behalf before the game's gods and gives us good things. Mississippi's last football hero, New Orleans' first football hero, the man who lost three times as many NFL games as he won, and the sire of four Super Bowl wins, Manning’s effect on the white, Southern, middle-aged male psyche is impossible to overstate. While Mississippi burned through the 1960s, Archie's quarterback play for the Rebels said, at least on the field: We're no. 1.

Archie Manning is the Lost Cause, the New South, Father Knows Best, and the Lombardi Trophy all rolled into one. No wonder he gets not one, but two, standing ovations from the Southern legislators.

His talk ambles sweetly through tales of his famous sons, as well as his own triumphs and struggles. When he turns to the platitudes one expects from a sports-figure talk ("While individuals may win awards, it takes teams to win championships"), he does so with the self-effacing grace of a small-town pharmacist.

When, however, he steps out from behind his prepared text, sidles onto a barstool, and takes lawmakers' questions, it gets interesting.

A tall, African-American gentleman approaches the microphone in the center of the room, 25 feet away, looks Manning in the eye and asks whether, now standing on Mississippi soil, Archie still wants to strike the Confederate stars and bars from the Mississippi state flag.

The room grows tense. Virtually the entire Mississippi House of Representatives is present, waiting. Manning, who saw plenty of blitzes up the middle, does not blink: "I supported that a few years ago, and I'm all for it."

Please, Saint Archie, say a prayer for me.

~~~

Just before Manning took the stage, Mississippi Lieutenant Governor Tate Reeves welcomed the lawmakers with a familiar call: "Our history is complicated, but our future is bright."

Reeves spoke specifically of Mississippi, but plenty of balding heads from elsewhere nodded. Whether under Democratic or Republican hegemony, the mantra for the New South since 1876 has been this: face forward.

But to what? And at what cost?

William Faulkner taught us the past isn't dead, it isn't even past. One need not observe that Jefferson Davis' last home (maintained by the Sons of the Confederate Veterans) is immediately adjacent to the meeting hall for the Southern Legislative Conference to appreciate that here.

All you need to do is walk around Biloxi.

Just 12 years ago, barely a sip of whiskey in the annals of Southern history, Hurricane Katrina's category-five winds pushed 12 feet of seawater atop downtown Biloxi. Dozens died. Those who fled to Jackson and Hattiesburg returned to find their homes, churches, and businesses washed away.

Some rebuilt, many did not. Biloxi's population is down more than 10 percent since. Just across Beach Boulevard from the city's high-rise casino hotels, lots scraped vacant by the surge still line the street.

Crossing one of those empty lots after a fried chicken dinner, I stumble upon a black granite monument in a small grove of trees, the monument's height illustrating the water's depth. Names of the Gulf Coast's dead and missing carved into the black rock call Maya Lin and her Vietnam monument to mind.

Some of the granite on this wall has fallen off, however, and three of the four lights intended to illuminate the memorial are inoperable, as if the statute of repose has run on this particular memory.

We want to believe our creative powers are bold and vast, but Biloxi whispers their limits.

Maybe the best we can do in the South in the face of challenge is to roll the dice in the 24-hour carnival of light and sound on Beach Boulevard's gulf side. Maybe it means nothing to note that where the waters crested under a live oak tree, the lights are out.

But, what if we crossed the road, and what if we turned them back on?