The Southern Monkee

/By Gabe Bullard

Forty-five minutes into our conversation, Michael Nesmith wonders if it’s getting “a little cosmic.” We’re talking about the differences between genres of music, and, by extension, the people who play them. Instrumentation, rhythm, clothes, attitude … all these come together to form the borders between honky-tonk and heavy metal, rock and rhumba. Nesmith, a musician, actor, and producer who has dabbled in several genres and styles, doesn’t care for these borders.

Look closely, he says, and it’s all just atoms anyway.

I hadn’t called Nesmith to get cosmic. I called to talk about a few particular sets of atoms he arranged in the early 1970s. After leaving the Monkees - the first manufactured-for-TV pop band that made him famous — Nesmith put out a trio of records that featured country instrumentation, pop melodies, folkie lyrics, and rock and roll performance. They have the steel guitar and swagger of the Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers (whose Gram Parsons-helmed albums had been released in the two years prior), but Nesmith’s work also has the type of casual California vibe the Eagles would smooth into soft rock standards later in the decade.

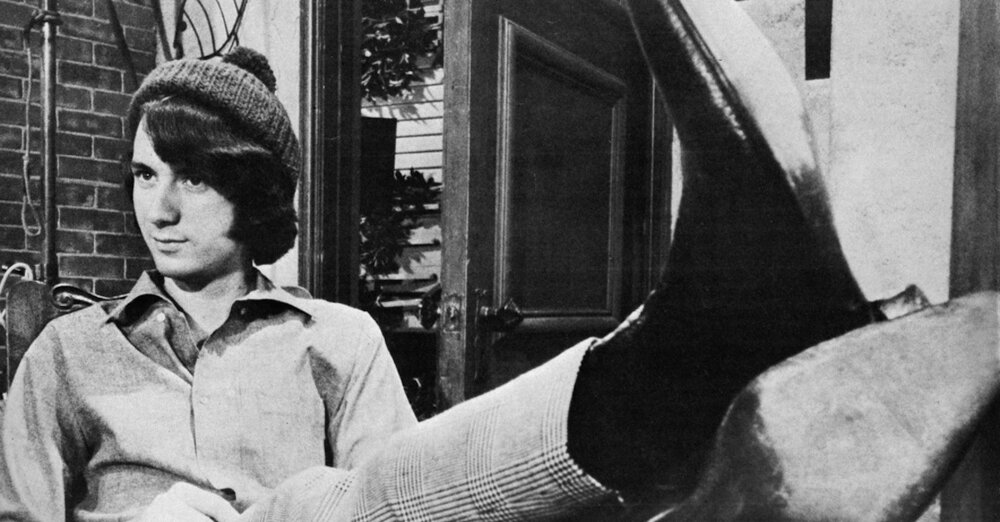

The Monkees in 1966 (Nesmith at bottom right)

In context, Nesmith’s work is pioneering. And like all pioneering work, it was underappreciated. His three country rock albums, made with a group he called the First National Band, only generated one hit — “Joanne” — and it stopped at 21 on the Billboard charts. In the canon of country-rock, Michael Nesmith is a footnote, neither a fan favorite nor a critic’s choice. He’s remembered more for his two seasons on an NBC sitcom than he is for his role in creating a genre of music (or for his invention of MTV, which we’ll get to later).

All this is why I ended up on the phone with Nesmith, talking about music on a molecular level.

“You’re caught in the same briar patch I’ve been caught in a long time,” Nesmith says. “Which is: How do you explain this crap?”

Nesmith laughs.

“I don’t mean to demean it by calling it crap,” he adds. “I’m just going colloquial on you for the effect.”

This is how Nesmith does an interview: He unravels my questions and addresses the logic behind them, then comments on his answer, giving context about what he said and why he said it. It doesn’t come off as neurotic or as meta for the sake of being cool; Nesmith just seems exceedingly aware that even the most mundane parts of life can have a deeper significance. Not everyone believes that. Of those who do, few seem willing to have fun with that significance. This helps explain why Nesmith never became Gram Parsons.

Throughout his career, Nesmith has been the most serious part of silly things and the silliest part of serious things. He was the most deadpan member of the madcap Monkees. On TV, as the band lip-syncs, Nesmith stands still, calmly playing his cream-colored Gretsch guitar in time with the music. His face is expressionless except for an occasional smirk or a light smile as the hook approaches. His eyes wander, occasionally drifting to the side as if he’s asking the director how much longer he needs to mime. In a performance of “Daydream Believer,” he wears thick glasses and a necktie, looking like a junior accountant at the office talent show. While the others groove and dance, Nesmith seems like he’s in a perpetual sigh. Tiger Beat said he was “cool without trying to be.” Viewers called him “the Smart Monkee.”

Nesmith was a working musician before he played one on TV. He had moved to Los Angeles from his native Texas a few years before the show started with hopes of being a folksinger. He emceed hootenannies at the Troubadour, a club frequented by just about everyone in the L.A. music scene, including Linda Ronstadt, who had a hit with the Nesmith composition “Different Drum.” Nesmith contributed a few of his own songs to the Monkees. The ones he got on air, including “Papa Gene’s Blues,” show his interest in combining country and rock.

The show gave Nesmith a gigantic audience for his music, but it didn’t win over critics. Writers in the mid-‘60s were taking rock and pop music seriously as an art form, but few saw the Monkees as art. It was basically a kids' show that co-opted the signifiers of pop and rock music. It wasn’t for sophisticated listeners. Rolling Stone derided songs on a Jeff Beck album with the phrase “dull as the Monkees.” In its 2004 album guide, the magazine summed up the band as “teenybopper fare that provoked shudders from anyone who took the Beatles at all seriously.”

The Monkees’ presence on TV helped record sales, but it only widened the credibility gap. In his memoir, Nesmith writes about his friend Jack Nicholson telling him in the late ‘60s why he’d never do television, using a familiar quote: “Theater is life. Film is art. TV is furniture.” A few people at the time, Nesmith included, could see that television was more than silly shows on a wooden box. New Yorker TV writer Michael Arlen called the medium “junk-plus-magic.” A pop band on TV may have been two layers of junk, but it was also two layers of magic.

“So many people loved the Monkees in a way they couldn’t explain that I was not alarmed that so many people hated the Monkees in a way they couldn’t explain,” Nesmith says. “It told me that we were on some sort of sacred ground.” (Later, in a sign of how seriously he took television, Nesmith made a short film for his single “Rio,” instead of shooting the traditional sing-to-a-camera style clip that record companies usually requested. When people liked it, he put together a pilot for a TV show of similar clips from various artists. He sold it to the Warmer-Amex company, which developed it into MTV.)

For Nesmith to add country twang to his mix of TV and pop was, as he would later call one of his albums, tantamount to treason. In his memoir, he writes about the difficulty he had getting Nicholson to go with him to see a country music performance in L.A. This was the era of Merle Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee,” when country was synonymous with conservative politics in many liberals’ minds. Now, here was the man previously known simply as Mike, the quiet member of a prefabricated band, shedding his TV persona and declaring that Hank Williams, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Jimmie Rodgers were as much an influence on his work as the Beatles, a group the Monkees were modeled on.

Anyone with a love of music could see the obvious connections between country and rock, and those who knew history knew how the two were related. But it took truly cool acts to sell a combination of the genres. Bob Dylan could pull it off. The Stones could dabble. The king of country rock, Gram Parsons, could make it art.

Parsons is a fun-house mirror image of Nesmith. Both were born in the South. Both had wealthy parents — Parsons was heir to an orange-growing fortune, while Nesmith’s mother invented Liquid Paper. But the resemblance stops there. Nesmith wasn’t raised rich. He dropped out of high school, got his GED in the Air Force, and moved to California with his girlfriend Phyllis Barbour, who was pregnant. Parsons had a trust fund that helped pay his way as he dropped out of Harvard to pursue music and eventually landed in the Byrds while he partied with the Rolling Stones.

“He had a hot badge,” Nesmith says of Parsons’ pedigree. “It put a gloss on his rhinestone suits, even though they’d been worn for years, and I’d gotten mine years before him.”

Parsons had a Nudie suit coated with pot leaves and pills, with a big red cross on the back. This smattering of rock irony on a hillbilly tradition could win over educated critics and country-music skeptics.

“Wow, this guy’s really smart,” Nesmith imagines a Parsons watcher saying. “And he’s wearing rhinestones. Is there something he knows that I don’t know? And the answer is: Yes, there is.

“People would look at him and think, ‘If he knows it, and we don’t know it, then maybe it’s really, really important.’”

Here again, Nesmith diverges from Parsons. He says this secret knowledge of country music isn’t important.

“It’s just popular music and it’s good fun,” he says.

This, perhaps more than his past with the Monkees, may have doomed Nesmith to a lower tier of the canon. He’s clearly having fun on his records. He yodels like Rodgers, and he closes side A of 1970’s “Magnetic South” with a rag jam and the declaration “we’ll be back just as soon as you flip the record over.” The followup albums, “Loose Salute” and “Nevada Fighter,” released in 1970 and 1971, respectively, feature similar antics between ballads.

Silliness and sadness were always side-by-side in country music; comedians played the Opry, too. But rock isn’t a place to have that type of fun. The Beatles got away with it early on, when the genre was still new, but their later jokes were tempered with reminders that they were capital-A Artists whose silliness was a sign more of their intelligent surrealism than of their love for a good punchline. Country-rock musicians could only have ironic fun — The Byrds singing the Louvin Brothers’ “The Christian Life,” for instance.

Nesmith’s approach was sincerer.

“It was never a feeling of anything other than trying to be very, very direct,” he says. “If irony showed up, it ridiculed the music. You couldn’t let that happen.”

Irony seeped from the cool parts of the scene into the reviews of Nesmith’s albums. Critics were generally positive, but overall dismissive. Robert Christgau gave “Loose Salute” a B+ but called Nesmith “Gram Parsons for television fans.” In at least two reviews, he calls Nesmith the Smart Monkee.

“I know irony when I see it, and I knew that it was a smart-aleck remark,” Nesmith says of the nickname. “It was meant as a backhanded compliment, and that was fine with me.”

This was the conundrum Nesmith was stuck in. He was too smart for the Monkees, too much of a Monkee for anyone to consider that smart.

If Nesmith hadn’t been in The Monkees — if he’d been an L.A. songwriter, contemporary of Gram Parsons and Glenn Frey and Linda Ronstadt, if he had been the musician who scored “Easy Rider” (as he says Dennis Hopper suggested) instead of a TV star, would the First National Band’s albums be on their fourth box-set reissue, instead of out-of-print (I found my 12-inch copy of “Nevada Fighter” in a literal bargain bin in suburban Maryland)? Maybe Nesmith would be a cult figure — the type of artist who isn’t widely known, but is deeply revered by those who know.

Just like the signifiers that mark genres of music, or types of people, Nesmith doesn’t care much for this type of question.

“It’s like asking me what would happen if Roosevelt hadn’t been elected president,” he says.

Maybe nothing could’ve changed the outcome. Maybe daring to have fun on a country-rock record would make anyone look like Howdy Doody compared to the too-serious-to-yodel, too-high-to-cry stars most associated with the genre.

In his book, Nesmith makes a comparison to a different famous puppet: Pinocchio. The Monkees were the fake band that became real. But no matter how much they moved on their own, people always saw the strings. Nesmith sets up this metaphor, but then he breaks it apart.

“Pinocchio is a wooden doll,” he says when I mention the idea. “So the idea that Geppetto would pray to a fairy to bring a wooden doll to life is evidence of insanity.”

Nesmith knows he was among the first to do what he did, but he portrays himself as more of an archaeologist than a pioneer.

“It’s a certainty to me that the music always existed. And that me and the guys just uncovered some of it,” he says. “You were swept along by the music. You did not sweep the music along.”

To ask why our cultural priorities discount things like TV comedies, pop music, and yodeling cowboys but venerate murder ballads and songs about heartbreak is to walk into a briar patch. Chasing Pinocchio gets Geppetto eaten by a whale.

There’s no changing Nesmith’s past. We can only celebrate it.