Words & Illustrations by Martha Park

Every summer, locals reenact the infamous Scopes Monkey Trial in Dayton, Tennessee, where Prosecutor William Jennings Bryan remains something of a hero. I wanted to see for myself why this story still resonates — particularly as conservative Christianity’s influence on contemporary politics has only grown, shaping legislation that seeks to restrict public education, reproductive rights, and gender expression. A century later, it’s hard to tell which side won the battle — and whether this is a war that can ever truly be won.

July 22, 2025

In the blanketing heat of late July I found myself in a packed courtroom in East Tennessee, watching history repeat itself. The tiny town of Dayton has hosted a reenactment of the Scopes trial every summer since 1988, the year I was born. The annual reenactment cycles through five scripts: Destiny in Dayton, One Hot Summer, Front Page News, How it Started, and the version selected for the summer of 2022, Monkey in the Middle. I’d heard that other scripts included musical numbers — bluegrass interludes. But Monkey in the Middle was a more literal interpretation of the trial, squeezing eight days of testimony and arguments, mostly verbatim, into a two-hour performance.

The 1925 “Scopes Monkey Trial,” as it was dubbed by Baltimore Sun reporter H.L. Mencken, centered around a high school teacher, John T. Scopes, who was accused of teaching evolution to his students in violation of Tennessee’s Butler Act. It was the first trial to be broadcast on the radio and was cast as a fight to the death between opposing sides. It was not just that either defense attorney Clarence Darrow or prosecutor William Jennings Bryan would prevail; in an era of polarized, symbolic politics not unlike our own, they represented a battle between the educated progressive and the Bible-thumping fundamentalist, the secular and the religious, the future and the past.

Whoever wrote the copy on the Rhea County Heritage Foundation website was well aware of the trial’s contemporary resonance, promising that the reenactment would rehash “arguments supporting Darwin or the Bible, majority or minority rights, parental control of schools, and much more.”

I’d bought a ticket for the reenactment the day the box office opened. As I drove east from my home in Memphis to the other side of Tennessee, I wanted to know what meaning this trial held — and still holds — not just for Dayton, but for the present-day melding of white evangelical Christianity and conservative politics. I wanted to know what is revealed about history and faith — and ourselves — when we reenact the same story year after year.

Clarence Darrow, far right, at the Scopes trial in Dayton, Tennessee, July 10-12, 1925. Photo: Everett Collection Historical

In the courtroom, the floor-to-ceiling windows had been covered in heavy black fabric; stage lights hung from the ceiling, and I settled onto the same stiff, wooden seats that had been present for the original trial. The director coached the audience: We would be responding to cues projected on a screen, prompting us to applaud, laugh, or murmur incredulously to each other, in accordance with the trial transcripts. Then the play began, with jury selection.

Every choice made while condensing a 336-page trial transcript into a script for a two hour play seemed hyper-deliberate, muscular, like watching a sculpture emerge from a block of stone. On stage, the actor portraying Bryan questioned a high school biology textbook that categorized humans as mammals. “How dared those scientists put man in a little ring like that with lions and tigers and everything that is bad,” Bryan bellowed. “These parents have a right to say that no teacher paid by them shall rob their children of faith in God and send them back to their houses skeptical infidels, agnostics, or atheists!”

In the front row, I watched several audience members’ heads nodding in agreement.

In one of the trial’s most famous moments, the judge barred all but one of the experts Darrow had selected to testify for the defense, Darrow finally called Bryan himself as an expert on the Bible. The proceedings moved out of the stifling courtroom and onto the courthouse lawn, where thousands gathered to watch as Darrow grilled Bryan on the age of the Earth, the provenance of Cain’s wife, and the precise date of the great flood. In the trial transcript, these interactions look ready-made for a script, with the characters volleying back and forth.

Blessed with air conditioning, we did not move outside for this portion of the reenactment. On stage, when Bryan hedged that the six days of creation described in Genesis might not have been literal, 24-hour days, but longer “periods,” Darrow lunged.

Darrow: “If you call those [days] periods, they may have been a very long time.”

Bryan: “They might have been.”

Darrow: “The creation might have been going on for a very long time?”

Bryan: “It might have continued for millions of years.”

Whenever Bryan appeared caught like this, the trial transcripts note outbursts from the gathered crowd or attempts to stop the questioning. (We, in the audience, were prompted by the projector to turn to our neighbors and murmur the word “watermelon” to conjure generalized consternation.)

Bryan insisted that Darrow continue: “The gentlemen have not had much chance — they did not come here to try this case. They came here to try revealed religion. I am here to defend it, and they can ask me any question they please.”

The projector screen hanging above the actors prompted us to applaud for Bryan, in accordance with the trial transcript, and we did.

Bryan’s time on the witness stand ended abruptly, when the judge announced that court would adjourn. The next day, the judge declared he would expunge the previous day’s testimony from the record. Scopes was declared guilty and ordered to pay a $100 fine, a ruling that was later overruled on a technicality. The reenactment ended as abruptly as the trial itself: The lights came up, and we rose from our chairs and began our slow exit through the courtroom’s double doors.

As someone raised in a faith tradition that saw science and faith as compatible ways of understanding the world, I never truly understood why conservative Christians opposed evolution so stridently. But as I stood in line to exit, I thought about one scene that illuminated the core of the conflict that I had not previously understood: The Butler Act, a state law passed in Tennessee in 1925, did not prevent public school teachers from telling their students that other animals had evolved; they were prohibited from teaching that humans had evolved.

On stage, Bryan paced as he asked one question after another: When, in that supposedly long and ongoing process of evolving, did people commit the original sin that propelled their fall from grace? And if people did not fall from grace, if there was no original sin, how did that change Christians’ understanding of salvation? And if there was no salvation, what did that do to the Christian assurance of life everlasting?

“They don’t tell us where man became endowed with the hope of immortality,” Bryan said. “They believe that man has been rising all the time; that he never fell from grace.”

The question of when man “shed his tail” and when he “acquired his immortality” were intimately related: If we are not the product of God’s design, created by God in God’s image, can we have evolved into God’s image?

To Bryan, evolution was an alternate origin story that could not be integrated into the one around which his faith — his entire understanding of the world — was structured, and proponents of evolution couldn’t meaningfully address, much less answer, these profoundly disorienting theological questions.

The audience spilled out onto the courthouse lawn, where the evening air had finally cooled. By the time I made it outside, most of the crowd had dissipated into the town’s quiet, half-lit streets. On the courthouse lawn, statues of Bryan and Darrow stood alone, forced to spend every night together in silence, under the stars. Behind the courthouse, the foothills that had seemed far away in the daytime suddenly loomed, navy silhouettes under a sky pitched toward night.

The trial pitted famous attorneys Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan against each other. Illustration by Martha Park

The 1960 film Inherit the Wind, a fictionalized account of the Scopes trial, has always been one of my dad’s favorite movies. Which seems strange, for a pastor, given the way the film lampoons religion. In the opening scenes, the townspeople travel as a mob, belting “Give me that Old Time Religion” and holding signs with slogans like “You Can’t Make Monkeys Out of Us” as they march around town.

But the religion represented by the characters in the movie bears no resemblance to my father’s faith. In his coverage of the Scopes trial, Mencken wrote that a United Methodist like my father “would be regarded as virtually an atheist in Dayton.” Some things have not changed; my dad, a retired minister, enjoys seeing fundamentalist Christianity get whooped by a Yankee agnostic as much as the next guy.

Inherit the Wind was itself an adaptation of a play written a few years earlier, when the Scopes trial was a vehicle through which to examine McCarthyism. And in the intervening decades, the Scopes trial has remained a mirror through which we try to see our own times more clearly. In the playwrights’ foreword to Inherit the Wind, they write, “The stage directions set the time as ‘Not long ago.’ It might have been yesterday. It could be tomorrow.”

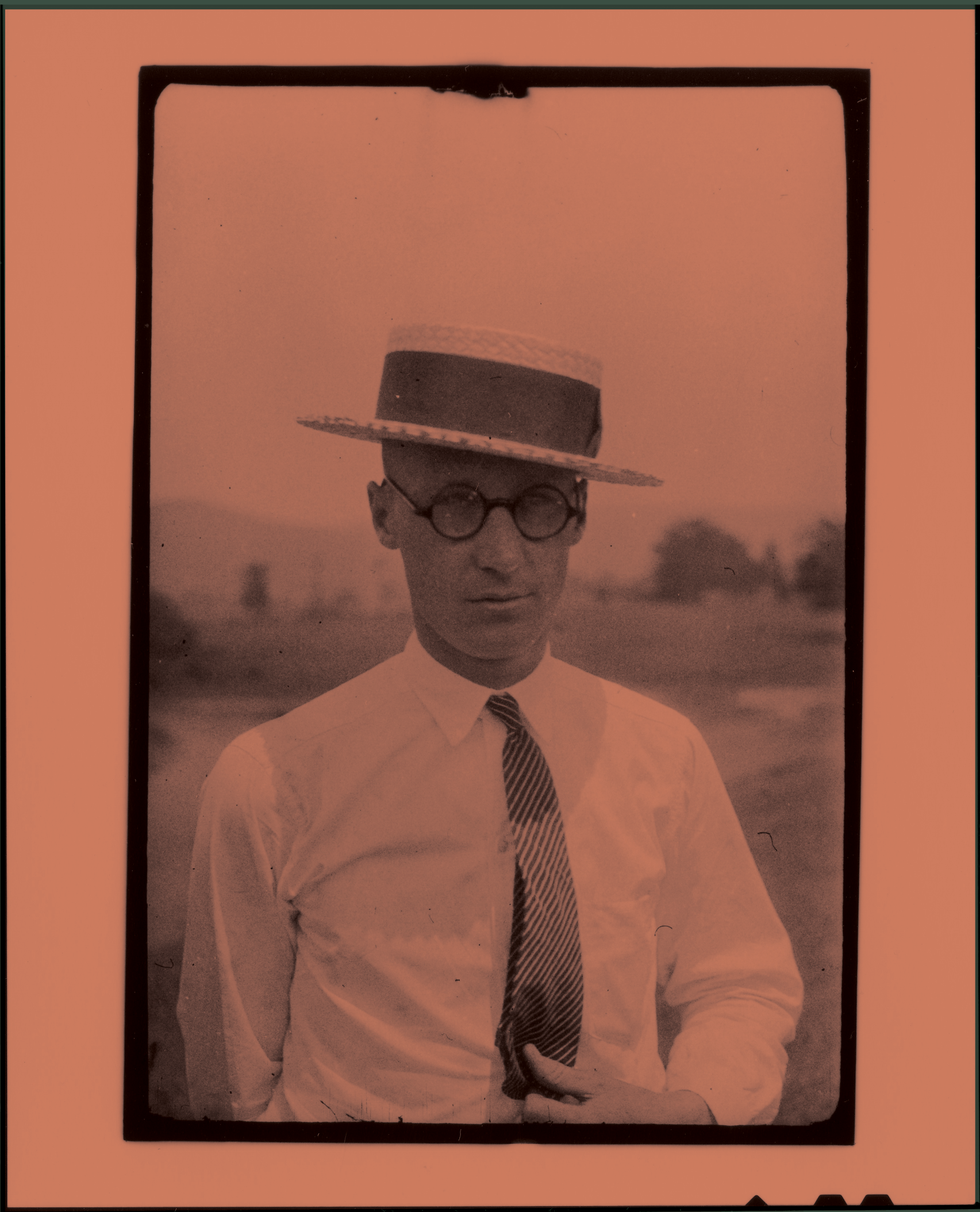

John Thomas Scopes, the teacher at the center of the 1925 trial that challenged his teaching of evolution in Tennessee public schools. Photo: Everett Collection Historical

The Scopes trial remains evergreen for the fantasy it presents of an ultimate ideological battle, where individual people are boiled down to avatars, fully embodying two opposing positions. In the myth of the Scopes trial, one side triumphs, once and for all, over the other. Except that it remains unclear which “side” actually won.

Before the Scopes trial, Bryan had lost three presidential elections as well as his bid for moderator of his Presbyterian denomination. But in Dayton, at perhaps the most high-profile moment of his career, he won: Not only was Scopes found guilty, but the Butler Act stayed on Tennessee’s law books until 1967 — more than 40 years after the trial.

The Sunday after the Scopes trial ended, Bryan took a nap after church and died in his sleep. Though Bryan spent much of his career in the halls of power in Washington, D.C., his death in Dayton seemed to bind him forever to this place, encasing Bryan, the Scopes trial, and Dayton together in amber. And although the story I’d always heard about the Scopes trial was that it was a moment of humiliation for fundamentalist Christians, somehow the end of something, it’s clear that Bryan’s death in Dayton was a new beginning, a sanctification; the town itself became a kind of holy ground.

When the trial ended, Darrow chose to forego making any closing remarks, which barred Bryan from delivering his own closing remarks. In the days following the trial, Bryan arranged for their publication. Arriving after his death, Bryan’s remarks, urging Christians across the country to build Christian colleges and universities, rose to the level of divine decree: Dayton’s own Bryan College was one of more than 70 Christian colleges founded across the country after the Scopes trial. Bryan College would become a leader in Christian apologetics and the formation of a Christian “worldview” for the next generation of white conservative Christians.

In the summer of 2025, the website for Dayton’s centennial celebration describes the Scopes trial as “a misdemeanor trial that in many ways never ended.” The fallout from the Scopes trial solidified in fundamentalist Christians’ minds what they’d always suspected to be true: That the world was not their home; that they existed in opposition to the rising tide of secularism and liberalism. That their battle was not, and perhaps by definition would never be, over.

In the 100 years since Bryan died in Dayton, he has been eclipsed in progressive Christian circles by Dayton’s most famous daughter, Rachel Held Evans, whose father was a professor of Christian Worldview Studies at Bryan College. After growing up in Dayton as a passionate evangelical Christian and attending Bryan College herself, Evans found herself unable to reconcile some of the beliefs with which she’d been raised.

In her first book, Evolving in Monkey Town (later retitled Faith Unraveled), Evans wrote about her upbringing in an evangelical faith that had been irrevocably shaped by the events of her hometown. “We were constantly reminded of the superiority of our own worldview and the shortcomings of all others,” she wrote. “As a result, many of us entered the world with both an unparalleled level of conviction and a crippling lack of curiosity . . . So prepared to defend the faith, we missed the thrill of discovering it for ourselves.”

Evans eventually concluded that theology “is not the moon but rather a finger pointing at the moon.” She gave up a quest for answers that would put all her questions to rest: “My hope is that if I am patient, the questions themselves will dissolve into meaning.” Evans went on to publish several more books before she died unexpectedly of an infection in 2019, at the age of 37.

I had imagined Evans as a figure telling a new story about Dayton. But no one in Dayton seemed to have heard of her, responding to mention of her name with shrugs, blank stares, lips drawn thin. If there is a religious figure Dayton wishes to align itself with, it is not Evans or her call toward a more nimble, humble faith. Bryan was everywhere; Evans was nowhere to be found.

In the courtroom, I sat next to a family of South Dakotans who had moved here for an academic job at a nearby university. When I asked them if they had read anything by Rachel Held Evans, the man sitting next to me leaned in close and whispered, “People like her have a way of disrupting systems of power in places like this.”

Aha, I thought, smugly. He was on my side.

A “Read Your Bible” sign on the privies outside the Rhea County, Tennessee, courthouse during the Scopes trial in July 1925 testify to the cultural clash surrounding the event. Photo: Everett Collection Historical

I hear echoes of the Scopes trial everywhere, but particularly in conservative Christianity’s influence on contemporary politics, in a rising tide of legislation attempting to restrict everything from public education to reproductive rights to gender expression.

Perhaps the fundamentalist beliefs driving recent waves of conservative legislation can be justified by certain interpretations of scripture, but it’s hard to believe this perspective on the world has been shaped more by faith than by the worldlier forces of power and politics.

As conservative Christian politicians rally around legislation stripping women of their bodily autonomy and reproductive rights; outlawing gender-affirming healthcare; all the while narrowing what perspectives on American history are allowed to be taught in the schools that they’re actively defunding, what they’re really doing is enforcing a kind of civic fundamentalism, attacking anything that falls outside of its rigid binaries and hierarchies.

It has always seemed weird to me that Christianity is even susceptible to this kind of binary thinking. Christ’s followers ostensibly model their lives and values after a man who was both human and divine; who was both dead and resurrected; who appeared, after death, to eat fish with his friends before ascending into heaven, and yet also remains alive, in spirit, for his followers 2,000 years later. (Not to mention they follow a man who explicitly associated his own arrival on earth with the end of binaries and hierarchies, saying: “There is no longer Jew or Gentile, slave or free, male and female. For you are all one in Christ Jesus.”)

Illustration by Martha Park

Many queer, trans, and nonbinary people of faith remind us that scripture does not and cannot contain the whole world. M Barclay, a nonbinary United Methodist deacon, writes that the creation story “talks about night and day and land and water, but we have dusk and we have marshes. These verses don’t mean ‘there’s only land and water, and there’s nowhere where these two meet.’ These binaries aren’t meant to speak to all of reality — they invite us into thinking about everything between and beyond.”

My friend Nathan left his conservative Southern Baptist upbringing behind when he came out, landing in the United Methodist Church just in time for its slow, painful split over the full inclusion of LGBTQ+ members. Almost a year after my trip to Dayton, Nathan and I went on a road trip across Tennessee and we talked, as usual, about theology. I wrote down something he said that day about scripture and thought about it often: “These texts don’t have any inherent meaning outside of the meaning that we as a community decide to give them.”

This sentence, shrugged off by Nathan as he drove, has stayed with me, returning to my mind often. I had never thought of scriptural interpretation as a decision made within the context of community, as a prism through which we could discern a community’s choices about what — or who — was important to them.

No matter whether you believe the Bible is the literal word of God, handed down from on high, or a collection of texts formed andrevised over centuries, the Bible doesn’t tell you how to read it, what meaning to take from it. It is too contradictory, too fickle, too strange to pretend otherwise. Any interpretation is a choice that says far more about the person or community doing the interpreting than it does about the text itself.

I had hoped that Christian fundamentalism might fade away as Americans continue leaving the church in droves, and as the percentage of Americans claiming any kind of Christian faith declines. Perhaps my personal dataset skews my expectations: Every year, my friend group expands to include more millennial “exvangelicals” engaged in the process of deconstructing the conservative faith traditions that formed them. Most of them, rather than trying to reconstruct a new version of their faith, end up leaving the church behind for good.

This particular portion of the decline in American Christianity comes not, as fundamentalists would like to believe, from the outside — from a secular, mainstream society’s corrupting influence — but from within. The writer Danté Stewart argues that the greatest threat to Christianity is not secularism, but certainty: “When you are so convinced that you are right, then you will create all types of enemies and cut yourself off from the ways God is active in another person’s experience.”

The former believers I’ve come to know have found that in attempting to create a sealed, static relationship with sacred texts and with God, fundamentalism creates a deeply unsatisfying theology that is at odds not only with complex human relationships in a constantly changing world, but with scripture itself.

But a decline in church membership and attendance doesn’t necessarily equal a decline in influence or power or even a change in beliefs. When the evangelical publication Christianity Today studied what happened when white Southern evangelicals left the church, they found that these former churchgoers “don’t lose the church’s political conservatism, moralism, or individualism. Instead, they become hyperindividualistic, strongly devoted to law and order, and overwhelmingly politically conservative.”

The conservatism, moralism, and individualism of white conservative Christianity can move beyond the church, shaping a person’s political identity and imbuing it with religious significance.

Christian symbols were on display during the January 6, 2021 insurrection: the crosses, the (white) Jesuses, the Bible verses printed on clothing and flags. In his testimony to a House Select Committee, a D.C. Metropolitan Police officer testified, “It was clear the terrorists perceived themselves to be Christians.”

When a religion becomes inseparable from political ideology, these symbols seem to depart from their previous associations and live out a kind of secular fundamentalism.

Shortly after January 6, 2021, the editors of Religion & Politics wrote a series of responses to the attempted insurrection. Lerone A. Martin, an Associate Professor of Religion and Politics raised in the evangelical church, warned of the dangers of “a white nationalist political party masquerading as a church.” He ended his letter by asking, “What does it profit a body of believers to gain political appointments and lose its own soul?”

National media seized on the controversy of the trial throughout 1925 and beyond.

Shortly after the reenactment, when I looked up the complete transcripts of the Scopes trial, I found myself drawn to the bracketed notes marking any audible interruption: [Laughter.] [Applause.] [A train whistle blows.] I found it so comforting to imagine the audience’s unruly reaction, or a train’s whistle so loud that all the arguments had to fall silent until it passed — all these reminders of a world continuing on outside the four walls of the courtroom. For all our attempts to create an airtight worldview, the world itself breaks through.

The morning after the reenactment, I checked out of my motel room. I stopped at a coffee shop named, of course, for Bryan, in a semi-abandoned strip mall surrounded by a bleak expanse of pavement. Mid-morning, I drove west, toward home, on empty highways threaded between gentle hills.

Though I had envisioned Dayton as a kind of outlier — a specific place where a specific story was retold over and over again, it seems to me now that if Dayton is unique in any way, it is only because it is so explicit in its refusal to leave the past behind, in its desire to relive it, year after year. In her book South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation, Imani Perry writes that we live in the past “as a changing same. The only possibility is reinterpretation of the scriptural underpinning.”

And it is reinterpretation I keep coming back to. If, in a place like Dayton, history were reinterpreted, rather than simply reenacted, how might that open up possibilities for new insights, revelations, and wisdom for our own time? It seems that whenever history, or scripture, or even beliefs cannot be reinterpreted, they cease to be living, instructive, or meaningful to our lives. They become, instead, the empty scaffolding of a worldview.

By being linked so irrevocably to the creation story found in Genesis, evolution now seems imbued with its own “scriptural underpinnings” and theological implications. As a new story — even as an alternate origin story — evolution suggests to me that people are not a finished product. Instead, we are the promise of ongoing change that will extend far beyond any of our individual lives. We have been otherwise before, and if we continue on this earth long enough, we will be otherwise again. Thanks be to God.

Illustration by Martha Park

On the highway driving west, I passed billboards claiming to speak for God. On the radio, on one station after another, men’s voices did the same. They all sounded so sure. I turned the radio off and drove in silence.

My thoughts turned to Rev. Harry Emerson Fosdick, once a pastor at First Presbyterian Church in Manhattan. In 1922, just three years before the Scopes trial, he preached a famous sermon reconciling science and faith. The impact of Fosdick’s sermon — titled “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?”— was seismic, as far as sermons go. John D. Rockefeller Jr. paid for 130,000 copies to be printed and mailed to every Protestant minister in the United States.

But before I ever knew about Fosdick or his most famous sermon, I grew up singing one of his hymns, often, in church. I found myself humming it as I began the long drive home:

From the fears that long have bound us

Free our hearts to faith and praise

Grant us wisdom, grant us courage

For the living of these days

For the living of these days. ◊

Martha Park is a writer and illustrator from Memphis, Tennessee. Her work appears in Guernica, Granta, Ecotone, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. Her essay “For the Living of These Days” is adapted from her new book, World Without End: Essays on Apocalypse and After.