The National Center for Civil and Human Rights

Atlanta’s Newest Landmark Will Teach Generations of Southerners What Doing the Right Thing Really Means

Back when I lived in New York City, people would ask me what it was like to live in Atlanta. I heard the question so often I developed a standard response.

I’d say: “You know that old saying, ‘It’s a nice place to visit, but you wouldn’t want to live there’? Well, Atlanta’s just the opposite. It’s a great place to live, but you wouldn’t want to visit there.”

This was my rather feeble attempt to express something that had gnawed at me during my years of living in Atlanta — the notion that there was no single place to visit that truly captured the heart of the entire city.

Other Southern cities were different. In Memphis, a tourist could easily touch its music-loving, barbecue-funky heart with visits to landmarks like Sun Studios or the Rendezvous. In New Orleans, the city’s genuinely unique, polyglot culture had created hundreds of ways for the visitor to feel its beating heart: through its foods, its architecture or that infectious Second Line beat that comes right out and says, “This is New Orleans music.”

And thinking about that begged other questions. What exactly was the heart of Atlanta? Where did one go to actually feel it beat? I suppose I’d grown up thinking that people thought the heart of Atlanta was in its rise from the ashes post-Civil War. But there were two problems with bringing that narrative to life for a visitor. One, it’s hard to see what remains of the ashes unless you do something hard, like go on a 10-mile hike through what remains of the Battle of Atlanta’s killing fields. And two, you wind up telling a story that goes something like this:

OK, our ancestors decided to fight a war that would allow them to keep people of color enslaved, and they lost that war, and in the process, my entire hometown got burned down.

Not exactly inspiring stuff.

But I knew — as did thousands of other Atlantans — that another story truly represented our city’s heart. Like the old tale, it was a story of struggle, but it was also a story of redemption, a story about a gift that Atlanta gave to the South, to America, and to the whole round world.

I also knew where that story began: on a half-mile stretch of Auburn Avenue in downtown Atlanta.

So when I moved back home and received out-of-town visitors, that’s where I took them. We’d drive or walk from Big Bethel AME Church at 220 Auburn, an African-American church whose roots reach all the way back to 1840, then eastward past Wheat Street Baptist Church at 359, and finally to Ebenezer Baptist at 407, just east of which lie the graves of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King.

These three churches, I would explain, gave birth to the American Civil Rights Movement. I would try to explain that in the 1960s, on this half-mile stretch of Auburn Avenue, America began to turn, to put aside its past and attempt to become a nation whose people, in the words of Dr. King, “will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

But my feeble words never seemed enough. And it was hard to just walk or drive past three churches and a gravesite in that five-block stretch and really feel the magnitude of the idea that took shape there — that reconciliation could triumph over conflict, that non-violence could overcome violence. The heart of Atlanta was there on Auburn Avenue, but it was too big and too ethereal to really feel as you stood on the sidewalks. You couldn’t dance to it, like you could a New Orleans rhythm. You couldn’t taste it, like Memphis barbecue. But it was there.

When the Olympics came to town back in 1996, there appeared downtown (at no small cost and a considerable amount of upheaval) a new public green, Centennial Olympic Park. Sadly, it instantly became known not as a watershed in the history of downtown Atlanta, but as the site of a bombing by anti-gay and anti-abortion zealot Eric Rudolph.

But over time, as happens in cities, things began to spring up around the park, including two of Atlanta’s biggest tourist attractions: the Georgia Aquarium, which opened in 2005 and has drawn more than 11 million visitors since, and The World of Coca-Cola, which moved to its current location across Baker Street from the park, in 2007, and brought with it another million or so visitors a year.

But yesterday, something else opened over by that park, and for the rest of my days it will be the first place I take visitors to my city.

I am certainly no architecture critic. Nor am I capable of projecting the economic effects of our new National Center for Civil and Human Rights. I can only tell you how I felt — as a Southerner, as an Atlantan, and as a human — when I walked out of the place for the first time last week.

I felt like the heart of Atlanta had finally found a home — a place that assembles all the bits of history and all the ghosts of martyrs you could feel in the air on Auburn Avenue and makes them shockingly, unavoidably real.

The National Center for Civil and Human Rights is a tremendous achievement, unlike anything this city has ever seen. It puts you directly into the experience of the American Civil Rights Movement, with all its heartbreak, and then takes you on a remarkable journey through the current struggles for human rights around the world and right here at home.

To judge it as a museum is to judge it unfairly. A museum is where you go to see things that used to be. The Center takes you through history, because you need that knowledge, but it does not let you leave before it challenges you to act.

And though the Center will get funding from those who buy tickets to visit it, its function is not merely to be a tourist attraction. The Center will be a place where people from all over the world will gather to do the very difficult work of reconciliation, of helping to create Dr. King’s “beloved community,” over and over again, all over the world.

It will be the place where current and future generations of Southerners will bring their children and grandchildren to learn the unvarnished history of our region. And it will be the place where those young Southerners will start asking each other questions they need to ask. By its very nature, the Center somehow makes all those difficult conversations easier to have. The logic of its narrative is simple: When the truth is right in your face, it’s hard not to talk about it. And by talking about it, the process of non-violent reconciliation that began on Auburn Avenue will continue.

You could call the place a museum, and you’d be right but not wholly right. You could call it a tourist attraction, and you’d be right but not wholly right. To me, it almost feels like a temple, in the larger, secular sense: “the structure of thought, value, or belief that enshrines the spirit or essence of something.”

Maybe we should just call it the High Church of Doing the Right Thing.

The idea of building this temple was hatched 11 years ago by the late Evelyn Lowery, a pioneer in the Civil Rights Movement along with her husband, the Rev. Joseph Lowery, and Andrew Young, a confidant of Dr. King’s during the Civil Rights Movement, a former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, and former Atlanta mayor.

By 2005, Lowery and Young had pulled other influential folks on board, including A.J. Robinson, the president of Central Atlanta Progress, a nonprofit community-development organization that’s worked since 1941 to build the economic vitality of downtown Atlanta, and Shirley Franklin, who was then Atlanta’s mayor.

Franklin had occasionally relied on the Atlanta office of Boston Consulting Group for pro bono work on broad community projects. One day in 2005 she asked BCG if they would volunteer a team of people to help evaluate whether the idea of a “civil rights museum” was viable. She specifically asked if BCG had any staffers with knowledge of civil rights history or museums.

The BCG partner who took the call replied, "We don't know anything about museums. We don't work in museums. We do have one guy here who knows a whole lot about civil rights history, but he's young and white. Does that make any difference?"

Mayor Franklin replied that if he could do the work, she didn’t care what he looked like.

Doug Shipman was the guy in question. He was then in his early 30s and fresh off a one-year posting with BCG in India. But Shipman didn't exactly fit the typical mold of the management consultant. He had come to Atlanta in 1991 from his tiny hometown in northern Arkansas, Bull Shoals, thanks to a Robert W. Woodruff Scholarship from Emory University. At Emory, he didn’t study business, but political science and economics.

Shipman had grown up in the Pentecostal church, but he had a different kind of conversion experience during his freshman year one bright spring weekend on Auburn Avenue.

“My town was all white,” Shipman says. “My town was all Protestant. My town had no diversity whatsoever. When I got to Atlanta, I got very interested in all of those issues, especially because they are the backdrop of Atlanta. My freshman roommate was from Arkansas, too, and that fall, we started touring the city. Emory took us on a visit to the Auburn Avenue district. I started going to services at old Ebenezer. I had grown up Pentecostal and so I knew all the music. It’s the same music except, you know, just different. I got very interested in the King legacy.

“Then I remember he and I, I think it was in the spring of ’92, went to the Sweet Auburn Fest. We saw James Brown perform on a stage under the Connector (the interstate highway through downtown that splits Atlanta into eastern and western halves). I thought, ‘This is heaven! James Brown performs for free in the middle of the city. It's incredible!’ But it also was one of the first times that I had been among 12,000 African-American folks. Me and my roommate, we were as white as white gets, and I thought, ‘This is so different and this is really interesting. Why isn't it always like this? This feels like what things should be like. Everybody loves James Brown. We’re all here, and it doesn’t matter what’s majority and minority.'"

That experience inspired him to take courses on race, women’s studies and religion throughout his time at Emory. The biggest eye-opener among those courses, he says, was a semester with Dr. Robert M. Franklin, studying the theologies of Dr. King and Malcolm X.

“He taught a course on Martin and Malcolm and their theologies and how they brought their religious perspectives to their social movements,” Shipman says. “I was totally turned on by that intersection.”

After two years in the corporate world, Shipman went to graduate school, not for the management consultant’s requisite MBA, but to study at the Harvard Divinity School. After three years in Cambridge, earning master’s degrees in divinity and in public policy, Shipman took a job with BCG in New York in 2001.

“Theology in a place like Harvard is as much about the ethical framework — the way that you make decisions ethically — as it is about religious perspective,” he says. “Half of consulting at a place like BCG is about the problem, and the other half is actually how you get everybody to move in the same direction. Every time I told a senior executive what I studied, they wanted to talk about theology. They wanted to talk about how you get a big organization all moving in the same direction. That's what religions do. They get a whole bunch of different people to believe the same thing or to move in the same direction or try to have a common perspective.”

Thus, when Mayor Franklin called BCG in late 2005 and asked for help with the idea that became the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, Shipman got the assignment. He and his team worked with Franklin, Robinson and other Atlanta community leaders in Atlanta through 2006. They studied 35 museums around the country and worked to hone a strong vision of what the idea should actually become.

“We still have it, this 150-page presentation with all of these data, all of the stuff about how you do it and what Atlanta's big opportunity was,” he says. “During that process, within the team and then with Mayor Franklin and with A.J. and a few other people on the project, this idea of civil rights and human rights coming together, of past and present coming together, of building up for the future … that’s what really coalesced.”

In 2007, Mayor Franklin asked Shipman to take a one-year leave from BCG to begin raising funds and exploring design options for the museum, which sits on land donated by The Coca-Cola Company. BCG agreed to hold Shipman's job open, and Central Atlanta Progress offered up office space.

It was supposed to be a one-year consulting gig, but Shipman never went back to BCG. He was learning too much.

Spend more than five minutes with Doug Shipman, and it becomes clear that one of the things he loves most about his job is the chance it has given him to meet and get to know the remaining lions of the Civil Rights Movement. He’s a huge fan of C.T. Vivian, the minister, now 89, who led many of the “freedom rides” that took young demonstrators across the South. He shares a story about Vivian’s dealings with Jim Clark, the white sheriff of Dallas County, Ala., the seat of which is Selma.

“C.T. every day got up early and went to the courthouse in Selma, and Jim Clark met him there almost every day,” Shipman says. “He asked for the people to be registered to vote, and Jim Clark would throw him in jail. Jim Clark would yell at him. Jim Clark would ignore him. One day, Jim Clark punched him. C.T. would pray for Jim Clark, go home, and come back the next day.

“I asked C.T. one time, I said, ‘Why did you keep doing it?’ He said, ‘Because I really believed that I wasn't just working for my own liberation, I was working for his, too. And I believed it could happen. Every day, I believed that we could be reconciled with one another and that Jim Clark could see that he was wrong and he could be better.’

“That is fundamental hope. That is tremendous hope. And all of the civil rights icons, all of them talked about that. It wasn't just about us. It was about everybody. It was trying to liberate everybody. And the truth is, this 41-year-old white guy sitting here is fundamentally liberated because of what those guys did. I'm liberated from having to live in that world. I'm liberated from having to be in a certain role because of me being white.

“I think that’s at the root of what this city fundamentally believes. This city had an aspiration, and it was able to bring that forward, even when it was tough. And that hopefulness is something that everybody needs.”

And that’s the story of how the greatest monument to the American Civil Rights Movement came to have as its CEO a white boy from Bull Shoals, Ark.

M. Alexis Scott is the Center’s vice president of member relations. She joined its staff in January after serving on the Center’s advisory board.

Scott took the job after a long career in the family business — journalism. Her grandfather, William Alexander Scott II, started a weekly newspaper for the black community in 1928 called the Atlanta World. Its offices were on Auburn Avenue, next door to Big Bethel. By 1932, when W.A. Scott turned 30, his newspaper had become successful enough to begin publishing every day. The Atlanta Daily World was, his granddaughter says, “the first black-owned daily that was successful and sustained in the 20th century.”

Scott’s family has been part of and witness to the American Civil Rights Movement since its beginnings. Her grandfather started the Atlanta World in a manner that exemplified what many call “the Atlanta Way” — meaning the uncommon level of cooperation that existed between the city's separate black- and white-owned businesses, even during the Jim Crow days. Mr. Scott sold advertising not only to black-owned businesses, but also to huge local and national advertisers such as Coca-Cola, Sears, and Rich's, which was the largest department store in Atlanta in those days. His editorial stance was firm but less confrontational than other black-owned newspapers of the day, particularly those outside the South. But his conciliatory approach to business and journalism did not protect him from a murderer’s bullet in February of 1934. The crime remains unsolved to this day.

In 1968, when Dr. King was assassinated, Alexis Scott was a 19-year-old student at Barnard College in New York City, directly across Broadway from the campus of Columbia University. She was home in Atlanta on spring break when he was murdered in Memphis. A week earlier, protests had broken out on the Columbia campus over the university’s affiliation with U.S. Department of Defense weapons research.

I ask her what it was like to to witness the simultaneous foment of the Civil Rights Movement and the change that was sweeping college campuses.

“It was a fascinating time,” she says. “I did march in the spring mobilization against the war in Vietnam where Martin Luther King spoke in New York City in, I guess, it was the spring of my freshman year. I was part of the Student African-American Society and the Students for a Democratic Society. I ended up dropping out of college and moving to San Francisco and caught the tail end of the Flower Power era.”

But by the early 1970s, Scott was back home in Atlanta, working in Newsweek magazine’s local bureau. To me, this seems entirely appropriate. “Flower power” was giving way to violence, but Alexis Scott was raised in the Atlanta Way. It makes sense that she would come home to the place where blacks and whites somehow made it through that era of change without the same scars of other Southern cities.

“Atlanta was a thinking person’s town. It’s a college town," Scott says. "You got Georgia Tech, Georgia State, the Atlanta University Center (home of the city’s historically African-American colleges, including Morehouse), Emory. You’ve got all this well-educated group of folks, and so you cannot say you didn’t understand. You cannot say you didn’t realize. You cannot say, ‘I didn’t know.’ That made the difference, I think, on both sides.”

I first got to know Alexis when I joined the board of directors of The Red & Black, the independent student newspaper at the University of Georgia, the journalism incubator for me and thousands of other Southern writers, reporters and photographers. Having served on that board for two years with Alexis, I felt comfortable enough with her during our recent interview at the Center’s new offices on Williams Street to bring up a what felt like a difficult topic.

“Does a it seem a little odd to you that a white boy from Arkansas is running the center?”

Alexis giggled.

“That’s the beauty of it!” she said. “They expect me to complain because I’m a black person and I lived in segregation, so I should be talking about it because I don’t want to have that kind of oppression or that kind of discrimination. But for a white person to do it, and especially a white man to do it, that makes all the difference because that’s the realization and acknowledgement that, you know, that there is some responsibility that you have in this equation.”

She recalled a moment during her nine months in the intense Leadership Atlanta program, which for 44 years has done executive leadership training among execs in the city.

“Somebody was complaining that, well, if you stand up, people can’t get on your back, and I said, ‘Okay. That is a good point; however, it is much easier for you to take your foot off my neck than it is for me to get my neck out from under your foot.’”

We both laugh.

“It goes both ways,” Scott said.

The broader impact of the American Civil Rights movement is on full display at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, and the Center’s ambition and reach is global. But for Atlantans, it also captures, more fully than anything before it, the fact that through all the confrontations and conflagrations of the movement, our city did not come completely unglued.

“Because there was this educated, middle-class group of people who were able to have kind of a peer relationship with the white leadership in the Atlanta community, they were able to work together to work things out,” Scott says.

Shipman sums it up pretty well with a deft turn on an old Atlanta business-community slogan:

“This was not a city too busy to hate, but it was a city that refused to explode.”

To attempt a description of the experience inside the Center is futile. The impact of its three galleries combined is too tremendous for words. Perhaps the best way to give you a sense of what happens to visitors is to focus on the difference between the experience of the National Center for Civil and Human Rights and most other museums.

Typical visits to museums end with the visitors discussing the things they saw — individual works of art or historical objects. People leave the Center, by contrast, talking about the stories they learned. This is not an unintended consequence of what the Center collects and displays. It happens entirely by design, owing largely to the thinking of a man named George C. Wolfe.

Wolfe’s name is instantly recognizable to theater geeks. He is a renowned playwright and director, an African-American son of Frankfort, Ky., who served as artistic director of New York City’s landmark Public Theater from 1993 to 2004. During those years, Wolfe won a Tony Award for his direction of “Angels in America: Millennium Approaches,” the first of Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer Prize-winning, two-part epic play about the AIDS epidemic and its effects on New York. He first gained national recognition for his play “The Colored Museum,” which was a series of 11 “exhibits,” or sketches, that both celebrated and satirized African-American culture. It’s was Wolfe’s first play to be produced at the Public Theater, and it began his long association with the Public.

In the initial research Shipman and his team from BCG had done, they had discovered something very interesting about the Center’s audience. Even though the events of the American Civil Rights Act seem so near to us in our history, the numbers suggested it would be wrong to assume that the Center would be telling a story that was already familiar to most people. In fact, according to U.S. Census data, only about 24 percent of Americans alive today were 6 years old or older when Dr. King delivered his legendary “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington.

In other words, most of us don't remember it.

So the team made a decision early on that the story of the Civil Rights Movement should be told as if the visitor had never heard it at all. When Shipman met Wolfe and discussed the possibility of his involvement in the Center’s design, that insight was critical to their discussions.

In their first meeting in New York, Shipman says Wolfe told him: "Well, I've never done anything like an exhibit or museum. But 'The Colored Museum' and 'Harlem Song' (Wolfe’s 2002 play) are both shows that in my mind were museum pieces, but the audience was stationary and play was moving in front of them. In essence, it was just the same emotion that you get when you go to a museum."

Soon after, Wolfe visited Shipman in Atlanta. “We went around and we looked at the site,” Shipman says. “We looked at the Auburn Avenue district and we looked at the AUC. We went to various places. At one point, George turns to me in the car and he says, ‘I don't quite know what you want from me. I don't quite have it in my mind.’ I said, ‘George, what would you be doing if you weren't a Broadway guy?’ He said, ‘I'd be a history teacher somewhere.’ I said, ‘That's what we're trying to do. You'd be a history teacher but do it in the language that you use on the stage, do it in that same sort of physical, visual, storytelling way around this history and around these issues.'

“Not too long after that, he drew a sketch,” Shipman says. “It wasn't an outline of the story. It literally was what looked like a floor plan.” Shipman begins moving his arms to suggest curving pathways. “It would go like this. It would turn here. It will have a curve and it would do this. He put it into almost rooms of museum experience. He said, ‘This is how I think the narrative goes. This is what I think it should look like.’

“And that drawing is awfully close to what you see six years later in the Center's exhibitions.”

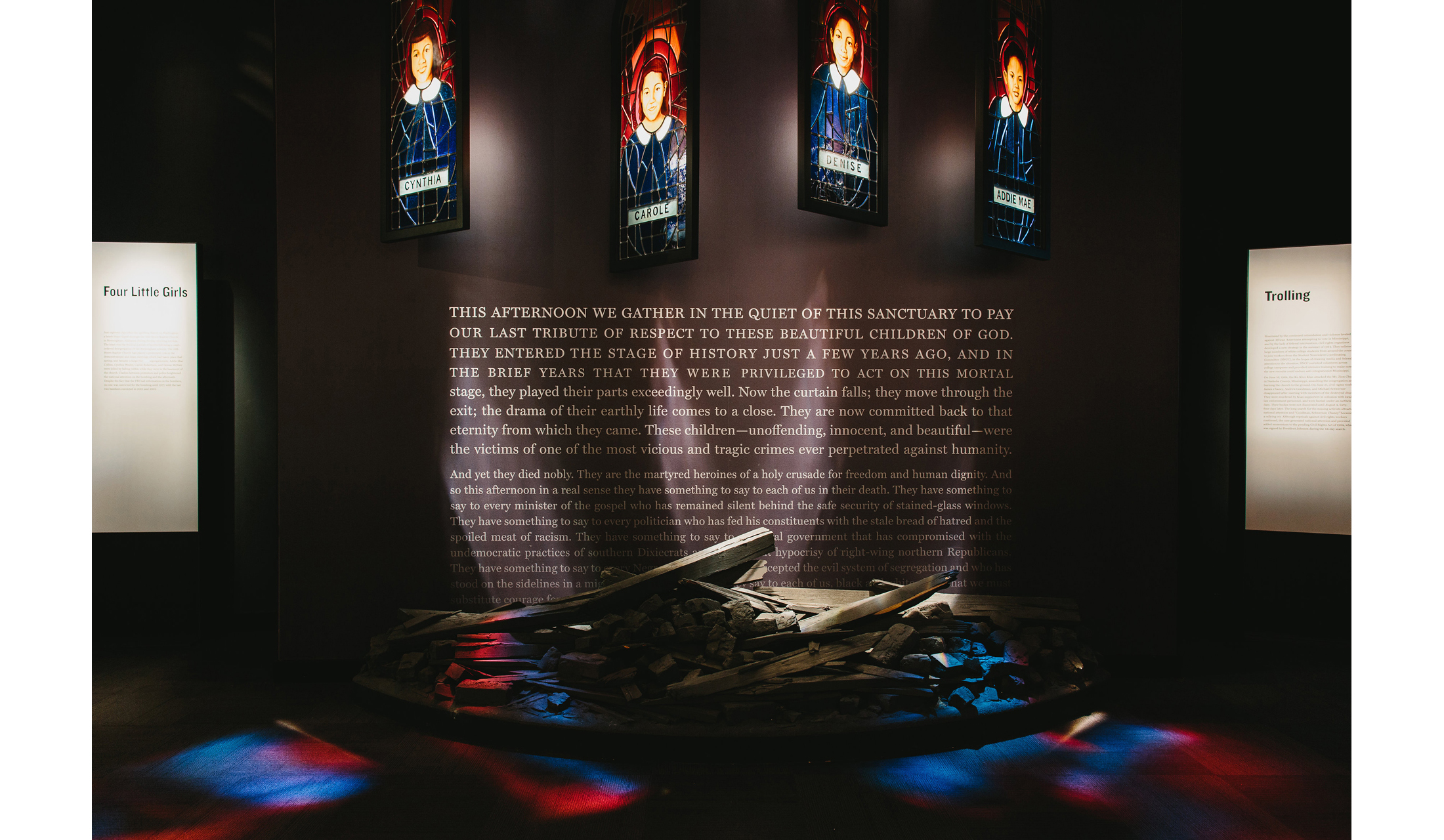

The center is broken into three galleries. The first tells the story of the American Civil Rights Movement, and that gallery, given its firm roots in history, will be the least likely to change over time. The second tells the stories of modern human-rights struggles around the world, and its exhibitions will change far more frequently as events change. The third — a quiet and dimly lit space on the lower level — will house ever-changing exhibits of artifacts from the papers of Dr. King.

The interplay between the first two galleries is what gives the Center’s story its power.

“George had always had this conception that there should be some physical connection between civil and human rights, between past and present,” Shipman says. “In this design, the way we manifest it, both the civil rights storytelling and human rights storytelling end at the same gallery. You go to that gallery twice. The idea is that even though you go to the same gallery twice, you will notice different things depending on if you come from civil or if you come from human.”

That small common space between the galleries reminds the visitor of the awful reality of all struggles for human rights: the fact that too often, those who fight for their rights die in the process.

Although the Center officially opened to the public yesterday, it was busy for most of last week as members of the press from around the world came through.

During my visit, I ran into Alexis Scott. She and another woman were sitting on a bench on the mezzanine that connects the civil rights gallery to the human rights gallery. They had passed the point in the story where Dr. King is assassinated in Memphis, and they were watching film of Dr. King’s funeral procession through the streets of Atlanta.

Alexis introduced me to her companion, Tina Sutton. Sutton had come there with her 88-year-old father, Ozell Sutton. I had never heard of Mr. Sutton before, but I learned about him quickly. Sutton, born in Arkansas, was one of the first African-Americans to be admitted to the U.S. Marine Corps. When he was in his late 30s, he’d been beside Dr. King at the March on Washington and in the terror-filled Selma-to-Montgomery marches two years later.

Three years later, he was also with Dr. King on April 4, 1968, when he was killed at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. Dr. King spent the night before his death in room 306. Mr. Sutton was next door in 308.

As I chatted quietly with Tina, who is now 62, she told me about her father’s work in the Civil Rights Movement. She also told me how she had attended Little Rock Central High School in the early years after President Dwight D. Eisenhower forced its integration in 1957.

As fascinated as I was by Tina’s stories, I could not take my eyes off her father. Ozell Sutton sat in a wheelchair in stunned silence, staring at a life-sized photograph of a man named Theatrice Bailey, the brother of the Lorraine's owner, on bended knee, scrubbing away the blood of his friend, the martyr, who had slept in the next room the night before.

In the Center’s human rights gallery, a remarkable interactive display allows visitors to explore various ongoing challenges around the world — everything from censorship to human trafficking. In each instance, the visitor is asked if he or she is willing to spend 60 seconds, 60 minutes or 60 days on the issue. Depending on which you choose, you get very specific directions about how you can educate yourself and take action.

A few days earlier, I had visited Scott and her colleague, the Center’s executive vice president, Deborah Richardson, in the Center’s new offices on Williams Street. Richardson grew up in Collier Heights, a neighborhood in western Atlanta that was the city’s first built by and for African-Americans. I asked them a difficult question: Sixty years from now, when all three of us will be gone (absent remarkable advances in medical science), what will the Center have accomplished? What change will it have brought about?

Richardson said she had already noticed that the Center was having a profound effect on young people who were among its early visitors.

“The immediate connection for young people when they go to the civil rights space is when they see how young those folks were,” Richardson said. “They see C.T. Vivian now when he’s 89, but then they see his mug shot when he was 30-something years old. They say, ‘Oh, my gosh. They were my age.’ And they ask themselves, ‘Would I have had the courage to get on the bus knowing I may never get back?’

“That will be the connection that anybody — across the races — is going to make, just the fact that these young people really did some courageous stuff,” she continued. “I absolutely do believe that we’re going to start some movement, some real social change action.”

I think Richardson could be right, and it fills me with hope to imagine that coming generations of Atlantans and Southerners will hear a different version of their region’s history — not the whitewashed one that the Daughters of the Confederacy have peddled for more than a century, but the unvarnished one, the real story about what happened when our forefathers forgot that living the Golden Rule requires loving every neighbor as yourself.

The story of Atlanta is simple, really. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman burned us down. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stood us back up again.

For most of my life, I’ve seen more monuments to the first part of that story than the last part — even though it was as clear as the nose on my face that the second part was the right one to emulate.

The National Center for Civil and Human Rights stands purely and triumphantly for the last part of the story. It stands proudly in downtown Atlanta, the city that refused to explode.

And it will teach generations of young Southerners the simple idea that’s explained in Article 1 of the 1948 International Declaration on Human Rights, which the Center has adopted as its foundational document:

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”