Michael Adno admired no artist’s work more than Alabama’s William Christenberry. And after Christenberry died in late 2016 at 80, Adno retraced his footsteps through west-central Alabama. Today, read through a two-year journey with Christenberry’s family and friends, recounting how he made a record of his native Hale County and what that ultimately meant outside the South.

Story by Michael Adno • Photos by William Christenberry

Store With Signs, Greene County, Alabama, 1974.

“Certain places seem to exist mainly because someone has written about them. Kilimanjaro belongs to Ernest Hemingway. Oxford, Mississippi, belongs to William Faulkner, and one hot July week in Oxford I was moved to spend an afternoon walking the graveyard looking for his stone, a kind of courtesy call on the owner of the property. A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his image…”

— Joan Didion, “In the Islands,” from The White Album: Essays, 1979

A summer squall tore the sky open one afternoon in Stewart, Alabama, when William Christenberry visited a cemetery near where his family had owned a farm since 1916.

As the dark clouds marched south — the rain giving way to bands of sun — he noticed the crepe-paper wreaths on the graves dripping lavenders, pinks, and a deep red. He remembered the sentinel oak tree watching over the place, the stand of pines at its edges, and the mounds that rose and fell, marking the lives of the people who lived there before him. But the pigments falling off those paper wreaths onto the red earth of west-central Alabama stuck with him. He made some photographs, then returned home and painted that graveyard. Fifty years later, he wrote, “That graveyard in Stewart was the first one I was interested in.”

In 2001, after Christenberry galvanized his place among the South’s most prominent artists (and one of the most adored in America), he told Andy Grundberg, “Whenever someone asks why I always photograph in Alabama, I have to answer that, yes, I know there are other places, but Alabama is where my heart is.”

Like Hemingway’s imprint on the green hills of Africa or Faulkner’s on Mississippi, Hale County belonged to William Christenberry — just as Memphis belongs to William Eggleston, Eatonville to Zora Neale Hurston, or Sacramento to Joan Didion.

Coleman’s Café, Greensboro, Alabama, 1971, and daughter Kate Christenberry holding a print of the photograph (photo by Michael Adno).

The thread of memory applied to all his work in sculpture, painting, and photography. But more clearly, he made visible the connective tissue between what places once were and what they were becoming. Walker Percy described Christenberry’s work as “a poetic evocation of a haunted countryside.” Walker Evans called Christenberry’s early photographs “perfect little poems.”

But apart from memory or time or place, pride and a deep sense of family coursed through his work. As Christenberry wrote, “When I travel, it troubles me to see how some people still look down upon the American South. There’s a stereotype that Southerners are stupid or uneducated, but that’s not the case. There are great artists who came from there, particularly writers and musicians. Jazz and the blues came from the South. Robert Rauschenberg was born in the South. Jasper Johns is from South Carolina.”

Christenberry’s career, which spanned five decades, with more than 100 solo shows, a 1984 Guggenheim fellowship, countless awards, and monographs, is testament to his point. Indeed, great artists come from here — Christenberry among them.

On November 28, 2016, William Christenberry died after a decade-long battle with Alzheimer’s. He was 80 years old when he passed away in Washington, D.C., the town he’d called home for almost five decades. A year after his death, I set out to retrace the footsteps of an artist I admired to no end. I went to Hale County, Alabama, to Washington, and to Memphis, seeking his family, his friends, and the places that affected him most. This was in no small part a pilgrimage — my attempt to pay homage to Christenberry and his memory.

Of course, I had no idea what the hell I’d find, or what I wouldn’t.

Grave, Windy Day, Stewart, Alabama, 1964 (left), and Chistenberry's painting "Grave II," 1963.

OLD MAN: You get old and you can’t do anybody any good anymore.

BOY: You do me some good grandpa. You tell me things.

— Robert Penn Warren, dedication in Being Here, Poetry, 1977-1980

William Andrew Christenberry Jr. was born in Tuscaloosa, Alabama in 1936. In 2009, he told an audience, “All my life, I wanted to be an artist.” Growing up, his family made frequent trips just south of town to where both sides of the family owned farms in Hale County.

That passage by Robert Penn Warren always conjured up a story that Christenberry’s maternal grandfather told him. As a kid, he’d chase hens and kittens around, and sometimes they’d vanish into a wall of kudzu across the road. Once, when Papa Smith saw his grandson tracing the edge of the kudzu, he called him over, put his hand on his shoulder, and quietly told him, “Son, don’t go out into that kudzu. There is a snake that lives there. When it gets riled up, it takes its tail in its mouth and comes out like a hoop, and it will roll right after you.”

That tale made a mark on Christenberry, and such stories forged a deep attachment to where he was from, for remembering what it was once like.

“I feel like I can reach out and touch memory. It can be manipulated, formed, shaped,” he wrote. “It certainly can shape you.”

In 1916, the Christenberry family moved to Stewart, Alabama, from neighboring Perry County, where Daniel Keener “D.K.” Christenberry built their home, and until 1950, when “age came on and their health began to fail,” the family stayed there. In 1951, D.K. passed, but the farm in Stewart never left Christenberry. He’d return annually from 1978 till 1996 to photograph a screen door on the side of the house and a tree on the property.

In 1944, Christmas brought a Kodak Brownie camera to Christenberry — an affordable little machine that made photography accessible to consumers in the 20th century. It wouldn’t be until a decade later, when he was enrolled at the University of Alabama and studying painting, that he began to use the camera. At that point, abstract expressionism was the lingua franca of the art world, and Christenberry often used the Brownie to make images he would later paint. He’d shoot the tenant houses and graveyards, then send his film to a drugstore for prints. In 2008, reflecting on those early works, he wrote, “I was trying to come to grips with my feelings about the landscape and what was in it.”

By 1959, Christenberry had graduated with a master’s of art and earned a teaching position at the University of Alabama. The following year, on a trip to Birmingham, Christenberry came across the second edition of the 1941 book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men by James Agee and Walker Evans. That book’s effect on Christenberry and the direction his career would take was monumental. The book became Christenberry’s “artistic lodestar,” as Matt Schudel aptly deemed it in The Washington Post.

Agee lived with the three families portrayed in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, which was born of an assignment from Fortune magazine to do a feature story on tenant farmers in rural America. Christenberry knew one of those families, or at least his grandmother did. Her family, the Smiths, lived on a farm just next to the Tingles, portrayed in the book as “the Ricketts.” When Christenberry showed her the book, she pointed and said, “Oh yes, that’s Mr. So-and-So.”

At first, it was Agee’s words, not Evans’ photographs, that cast a spell over Christenberry, but in time that would change. “What Agee was doing in the written word was what I wanted to do visually.” After all, he always admitted he most admired poets.

Coleman’s Café, Greensboro, Alabama, 1967 – 1996.

After a year of teaching in Tuscaloosa, one of his mentors, Melville Price, told Christenberry he needed to venture out beyond Tuscaloosa or “be forever trapped there.” In 1961, he set out for New York City.

His first year there was the only dry spell of his career, but he stumbled into what might have been the most fecund expanse of land yet. He held eight jobs while he was in the city. He worked in retail, as a custodian, and even spent a single day as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art. Finally, he worked up the nerve to call Walker Evans, who was then a senior editor at Fortune, and Evans agreed to meet. Evans even secured a job for him as a file clerk in the photo department at Time-Life.

The two took to each other, and when Evans learned about Christenberry’s photographs he asked to see them.

“I put him off,” Christenberry said. “I was scared.”

Sometime later, Christenberry brought his work to Evans’ place. Evans took the box of drugstore prints and went over to another part of the room as Christenberry talked with Evans’ wife, Isabelle. The seconds passed like molasses through a sieve, and he thought Evans might never finish. Finally, Evans looked up and said, “Young man, there is something about the way you use that little camera. It’s become a perfect extension of your eye, and I suggest you take them seriously.”

The Bar-B-Q Inn, Greensboro, Alabama, 1986.

In 1962, Christenberry left New York for a teaching position at what was then Memphis State University. Christenberry, who was blind in one eye, needed the money to cover medical care, and so the job buoyed him. In Memphis, there was another young photographer by the name of William Eggleston, and one night Christenberry invited him over to his place. The two ended up at a cafeteria across the road and then a laundromat, sitting up on the machines, telling stories, late into the night. This was the start of a friendship that would last a lifetime, but it was also something else.

After seeing Christenberry’s little drugstore prints at his home, Eggleston started shooting in color. At the time, color photography was used mainly in commercial settings. The fine-art world looked down upon it. Once, when Eggleston was seated with one of his early influences, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bresson told him, “William, color is bullshit.”

“Excuse me,” Eggleston said, and left the table.

“I thought it was the most polite thing to do,” he told John Heilpern in 2015.

“It’s interesting to think that if Evans hadn’t encouraged Christenberry to go back South, Eggleston might still be a black-and-white photographer,” the museum curator Walter Hopps wrote in a posthumous essay. In 1976, the Museum of Modern Art devoted its first solo exhibition of color photography to Eggleston, earning him the title of color photography’s forbear. The two, Christenberry and Eggleston, altered the arc of photography forever, just as their fellow Southerners Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns had painting. After only 14 months in New York, Christenberry moved south to Memphis, and there he would start his own family.

Sign Near Greensboro, Alabama, 1978 (left), and Corn Sign With Storm Cloud, Near Greensboro, Alabama, 1977.

One night in November, Christenberry, clad in a brown bomber jacket and white silk scarf, hand on the wheel of his white 1964 Mustang, peered over toward the passenger seat across the blue interior to his date, Sandra Deane.

“Now, I’m going to introduce you to some of my friends. We’re having a sort of event,” he said. “I have to leave for a while. Do you mind?”

Sandy told him, “No, that’s okay.”

The two were pushing north towards Christenberry’s studio at the edge of the university, where he taught and Sandy was a student. It was Christenberry’s birthday, and he’d finally persuaded Sandy to go out with him.

Inside the studio, the place hummed. Christenberry, the host, introduced Sandy to a few of his friends, and then fell away.

Suddenly, Sandy and the rest of the crowd were asked to move out into the alley alongside the building. At the far end of the alley, lights burned, but nobody had any clue what the hell was going on.

“Out of the darkness,” Sandy remembered, some young man with a roll of butcher paper unfurled the thing like a red carpet down the gravel drive, then disappeared back into the night. Folks pressed up against the edge of the studio wall as a beautiful Bentley convertible floated down the alley, a man in the driver’s seat, a woman next to him in a couturier hat, and another figure in the backseat — all dressed in black wearing white masks. About halfway up the drive, the car came to a stop as a toilet descended from above, suspended from a rope. The man in the backseat stood up, cut the rope, sending the toilet into the seat next to him before the car took off.

Sandy, a drink in one hand and a cigarette in the other, just thought, What? This was long before performance art had any nomenclature, before Fluxus was a thing, before any “happening” had happened.

Behind the wheel, Eggleston sat next to his wife Rosa. In the back, a teenage Alex Chilton. And up above, Christenberry lowered the toilet.

“You will not believe the date I had last night,” Sandy told her parents the next day.

Just before Christmas that year, Sandy went to visit her boyfriend at the time in Atlanta. Christenberry wasn’t exactly thrilled, Sandy explained, especially since he’d given her a drawing of a red rose with a gold leaf frame just before she left. But Sandy believed she’d marry him. And on that trip, she thought she’d return engaged, but instead, the boy broke up with her. Once she got back to Memphis and collected herself, she told Christenberry, and he asked her out again.

They began dating in 1966, and by August 19, 1967, they married. They moved to D.C. the following year, and then came their first daughter, Emlyn, in 1970, Andrew in 1972, and Kate in 1981.

“And now here we are,” she told me as we cupped our glasses of whiskey in December of 2017.

Sandy Christenberry at home in Washington, D.C., with her parakeet, Okra, in October 2018 (photos by Michael Adno).

Inside the Christenberry home along the edge of Rock Creek in Washington, the house was warm as the pale light outside signaled an approaching spell of snow in December. Sandy, her daughter Kate, and I looked outside as the pall of winter fell over the city.

The family bunny, Bean, kept an eye on us from across the room filled with books, photographs, and the sense that a life had been lived here. One year and 10 days earlier, Christenberry had died.

The house was quiet save the wind pressing up against the bare trees outside. “Last August would have been our 50th anniversary,” she said as we broke the silence with a commingling of crystal glasses, before Sandy added, “To dad.”

William Christenberry’s studio in Washington, D.C., which he built on the property adjacent to the family's home in 1984. Michael Adno photographed this view of studio in December 2017.

“They are not self-portraits, but they’re everything I know.”

— William Christenberry, 1983

About a month before I visited his family but after getting their blessing to pursue this story, I drove to Hale County, Alabama, to retrace Christenberry’s footsteps. I planned to visit the sites he photographed, to meet some of his friends, some family, and assemble some sense of what his work meant to me as a photographer and as a Southerner, because for as long as I could remember, William Christenberry’s work loomed larger in my mind than any other artist, writer, or musician. My goal was to build out of the bones of this story, but I had little idea of what I’d find — if anything.

The clock pushed back an hour as I crossed from Georgia into Alabama — from Eastern Standard to Central Standard. I was driving over from Atlanta in the middle of the night. I holed up in a little haunt outside Tuscaloosa, but I could barely sleep for wanting to see Hale County come first light. As soon as a bit of blue spilled into the sky, I headed south.

From the eastern edge of Tuscaloosa’s city limits, I drove down backroads, traversing river after creek after hollow. As I made my way down, sprawling urban creep spilled out over the meandering hills south of town. Shingles and cul-de-sacs extended as far as I could see. Passing over recently paved roads that rose and fell through the pines, the residential areas grew thinner. Kudzu crept toward the roadside, and trailers sat next to ranch houses overlooking the forest. I started to get glimpses of what was in store as I came into Christenberry’s territory.

I pulled off in Moundville to map where I was headed. I had only a vague sense of where certain sites were. The sun was still hanging low, lighting up the unoccupied storefronts of the main drag in a deep chiaroscuro. I typed in the coordinates of China Grove Church.

In 1977, Lee Friedlander suggested Christenberry try making photographs with a large-format view camera rather than the Brownie. He took the advice and hauled an 8x10 Deardorff — loaned to him by Caldecot “Cotty” Chubb — to Hale County along with 30 sheets of film. “I didn’t know what I was doing,” Christenberry admitted. He asked a commercial photographer in Tuscaloosa to help him load the film. He double-exposed the first sheet.

From his early years shooting sheet film, one image stays with me. Christenberry’s photograph of China Grove Church in 1979 held a mysterious draw for me — a white clapboard vernacular church set back in the woods with a vein of red clay carving toward it. Hell, I’d been trying to find a place as haunting in Florida to photograph for years, but of course I never did.

Sign Near Moundville, Alabama, 1975 (left), Triangular Gourd Tree Near Tupelo, Mississippi, 1976 (center), and Grave With Egg Carton Cross, Springhill Cemetery, Hale County, Alabama, 1975 (right).

I sped out Clary Hill Road where a polished metal sign with black vinyl letters pointed toward China Grove, and after a few miles, another sign confirmed I hadn’t gone too far. I was waiting for the road to drop off into clay, but before it did I saw a big buck’s silhouette on the road ahead. We stared at each other for a moment, then the stag took off over a bank into the woods. Just past the deer, China Grove stood at the bend.

For a moment, it felt like finding something that belonged to Christenberry. It felt wrong, almost shameful, to point a camera at the building. A few hundred yards down from the church, where the woods closed in on the little structure, I stood alone and listened to the wind in the trees. In 2008, Christenberry looked back on that image and explained that, for a long time, he wanted to “capture the feeling of aloneness of a beautiful church down a country road.” Something like that came over me. As he said, “This one did it.”

From there, I followed the road deeper into Hale County and found myself on the side of a logging road, on the phone with Sandy and Christenberry’s son, Andrew, trying to pin down the site of the Palmist Building.

Where SR 60 and 69 meet in Havana Junction, a flatiron plot of land extends south where there used to be a few cedars and chinaberry trees along the road. Just after World War II, Christenberry used to tag along with his father on Saturday when he was making deliveries for Sunbeam bread. From Tuscaloosa, they’d come down 69 then hook east toward Marion by way of Greensboro and return the same way. In Havana Junction, where the road split, Christenberry’s uncle Sydney owned a general store they’d stop by on their way home. Later, when uncle Sydney gave the place up, a group of Romani palm readers took over the space, and some indeterminate time later, they fled town with their rent unpaid. In their wake, they left some bad faith and a few signs that Christenberry started photographing in 1961 along with the building. One hand-painted sign of a palm stuck in a window upside down became a sort of obsession for Christenberry.

The sign from the Palmist Building in Havana Junction, Alabama, hangs in Christenberry’s studio after a years-long negotiation with the owners to acquire the sign (note the egg-carton cross framed below it)m and a detail of Christenberry’s studio wall showing signs he collected over decades of trips home to Hale County (photographs by Michael Adno).

On the phone with Andrew, I’d come into this little expanse of fill dirt and gravel behind a general store at the split, and I was pacing around with a monograph in one hand, phone pressed to my ear in the other. No remnants of the building remain, save a cedar tree that used to split the building in half, along with a single chinaberry tree. After the better part of an hour doing concentric circles while trying to discern where the building stood, I wandered off down the road and another picture Christenberry took in 1973 returned to me. It was a photo he made of Walker Evans photographing the Palmist Building when they returned to Hale County together in October, 1973. In the photo’s background was a sign for Moundville and Tuscaloosa, and when I saw the contemporary sign in the same place, I knew where the building stood. I’d been standing on the site the entire time.

Site of Palmist Building, Havana Junction, Alabama, 1988.

This continued each day with family, friends, and anyone willing to point me in the right direction. One person always sent me to another if they couldn’t help, and there wasn’t a single person who couldn’t find the time.

When I arrived, I had the edges of Hale County put together like the border of a jigsaw puzzle, and by the time I left a week later, spending each day and even some nights visiting and searching places out, I filled in a portion of the puzzle, but there were several pieces I wouldn’t find until a year later — if ever.

“Time is the air we breathe, and the wind swirls us backward and forward until we seem so reckoned in time and seasons that all time and all seasons become the same.”

— Donald Hall, Dock Ellis in the Country of Baseball

Just north of Moundville, at the top of a broad hill separating Tuscaloosa from Hale County, Judge Sonny Ryan waited outside Big John’s Barbecue on a warm afternoon in November. The round quality to his drawl and thoughtful cadence reflected the 25 years he spent as a jurist in Hale County. Inside, across a Formica table set with pulled pork, smoked chicken, and fries, he said, “Bill and I met in a roundabout way.”

Down in Greensboro, Christenberry’s mother worked as the Hale County tax assessor, and the judge knew her and her niece, Teresa, who was Christenberry’s first cousin. And once, in the 1990s when Christenberry was set to speak in Tuscaloosa, Judge Ryan drove up SR 69 to hear him speak. During that presentation, he saw countless tenant houses he knew from childhood, signs he’d been face to face with, and landscapes he drove by every day. In a way, it made the drive home more meaningful.

When Judge Ryan visited D.C. sometime later, Teresa told him to give “Billy” a call. The Judge was unsure, but nevertheless he did, and Christenberry told him to come on by. Then, in the studio, the Judge lit up again, because the signs that adorned the walls were markers he knew intimately.

“That’s a thermometer that came from the Bank of Moundville. I know because I gave away about 5,000 of ’em,” he joked.

But this wasn’t the story I wanted the Judge to tell me. I wanted to know about a particular favor Christenberry had asked him for.

There’s a little building out in the Talladega National Forest, a squat structure with a gable roof. Christenberry called it “Red Building in Forest,” because someone had wrapped the entire thing in faux brick tar paper. He found it humorous and surreal and would drive the 12 miles out into the forest to photograph it almost every year since 1974.

In 2000, After Christenberry had photographed the place for 26 years, the county placed a pre-fab metal shed in front of the building, and while Christenberry continued to shoot it, the new building was an eyesore, making it impossible to photograph the facade of the Red Building. And then in 2001 during Christenberry father’s wake, the Judge offered Christenberry his condolences and told him, “I want you to know I really have come to appreciate what it is that you do.” The Judge explained how he often drove past the Red Building on his way to Birmingham, and that he noticed the new building. So, in the span of that moment, even with the fogbank of grief hanging over him, Christenberry asked the Judge, “Is there anything you could do about that?” The Judge would see.

Two weeks later, the phone rings. “Bill, this is Sonny. It’s gone.”

The county engineer moved the building 10 yards to the left and even re-sodded the dead patch of grass where the pre-fab building stood before.

So, back in November, 2017 at Big John’s, the Judge and I filled up our cups and headed out the door to the Red Building. It only made sense that the Judge take me.

Red Building in Forest, Hale County, Alabama, 1974 – 2004.

Traversing the backroads, we sped through canopies of old growth as the houses grew further and further apart with every curve. Twelve miles out, we were deep in the middle of nowhere driving down a thin ribbon of asphalt hemmed in by pines.

I felt the brakes engage, and the Judge made a turn onto a tiny patch of level ground just next to the Red Building in the Forest. As every other site, it was strange to look at, to touch, to be there especially with somebody who knew and was from this place.

“I told Bill some things about this place he didn’t know,” the Judge said. More than a century back, it was a one-room schoolhouse where his wife’s grandfather taught. Later, it became Beat 13 of Northeast Hale County to serve the 21 voters out here. (In Alabama and Mississippi, it seems, election precincts are called “beats.”) The new building arrived to replace the former.

“There’s not a whole lot to do out here,” the Judge joked when he saw the bullet holes in the windows of the new building. A torrent of wind carried through the woods toward us, but save the wind and the whir of cicadas, it was silent. We stood together and looked onto the Red Building in the Forest — not a word.

Red Building in Forest, Hale County, Alabama, 2017 (photo by Michael Adno).

On the way back, we hooked onto a winding road along a stream, and the Judge looked off into the trees. “This is Kings Hollow. I can still drive that road today, and I could be 5 years old,” he said, explaining how his ancestors settled here in this part of America, of how he came to that church as a boy “three buildings ago.”

That sentiment — to me — made clear what drew the Judge to Christenberry’s work. It was a shared reverence for the ancestral past that many held dear, and it was almost spiritual to revisit these places as Christenberry had annually for five decades. The Judge recognized that. “The feeling washes over you,” he said, “Or it does me anyhow.”

Earlier when we were eating, the Judge tossed down his sandwich, pawing at a napkin before he said, “Let me go ahead and get this over with, because I have a hard time telling it.”

In the years before Christenberry’s death, Teresa had called the Judge to let him know Christenberry was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

“We kept talking about going to see him,” he said as his shoulders rolled inward and his head fell. “Going to see him, going to see him.”

Some time passed, and Teresa phoned again: “Sonny, talk to Bill while he still knows who you are.” They dropped everything and flew to D.C.

At lunch together, Christenberry told him, “Judge, I’ve got something wrong in me right now, something wrong with my mind. But next time I see you, I’ll be well.”

“Bill, I know that’s true,” the Judge told him.

The Judge wiped tears from his eyes and searched for the words. “We didn’t see each other that often,” he said. “We just connected.”

“From these woods a good way out along the hill there now came a sound that was new to us.”

— James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

In 1936, when Agee and Evans came to Hale County, one of the families they stayed with lived on Mills Hill between Havana Junction and Moundville. Some of Christenberry’s earliest paintings and photographs depicted tenant homes in that area. I asked the Judge if he knew where it was, and he thought it might be just past his house a bit, past the wide spot in the road, right after the flashing light. I cut up that road and found my way to a few dead ends before the road fell off into red earth climbing up a hill. As I swung around one bend, the late afternoon sun lit up a set of tenant houses along the road, and a current seemed to pass through me. This was hallowed ground.

I was given to rereading Let Us Now Praise Famous Men often this past year, and it’s difficult for me to pin down where the book ends. Before the second edition would reach the press, Agee died in 1955, garnering a Pulitzer three years later for his novel A Death in the Family, but he never saw the wellspring Let Us Now Praise Famous Men became. In the preface, Agee laid out a sort of living will for the work, and in it, he suggested that it was designed to be the beginning of a larger work.

Christenberry seemed to take that invitation as his own departure point.

Walker Evans at the Palmist Building, October 1973, by William Christenberry, and Allie Mae Burroughs, Alabama, 1936, by Walker Evans (courtesy of the Library of Congress).

I thought of the Agee lines that seemed to form Christenberry’s credo later: “If I could do it, I’d do no writing at all here. It would be photographs; the rest would be fragments of cloth, bits of cotton, lumps of earth, records of speech, pieces of wood and iron, phials of odor, plates of food and of excrement.”

There at the top of Mills Hill, I thought back on how an entire era of social documentary had sprung up from this place in Alabama. In some ways, it had bent the arc of America. I walked around the grounds, trying to keep away from any rattlers, thinking on the work carried out here long before Agee or Evans or Christenberry. Among the rundown dog trots and chapels, the deer runs and winding red ribbons, Christenberry returned time and again, just as a litany of disciples following in the footsteps of Agee and Evans also had — like I had, too. But after decades of those annual trips home, Christenberry made a copious record of what it means to belong to a place.

And now, looking out over the farms and stands of pine marching further South with my feet planted firmly in the same plat of red earth as Agee and Evans and Christenberry once stood, I realized this was my own “courtesy call on the owner of the property.”

Elizabeth Tingle, Hale County, Alabama, 1936, by Walker Evans (left), Elizabeth Tingle Near Akron, Alabama, 1962, by William Christenberry (center), Near Akron, Alabama, 2017 by Michael Adno (right).

“In art, and maybe just in general, the idea is to be able to be really comfortable with contradictory ideas. In other words, wisdom might be, seem to be, two contradictory ideas both expressed at their highest level and just let to sit in the same cage sort of vibrating.”

— George Saunders

In 2006, as the morning dew burned off at the edge of Chinatown in D.C., Robert Olin, the dean of University of Alabama’s art department, waited at the foot of the steps leading up to the newly restored Smithsonian American Art Museum. Part of the Museum’s post-renovation program was a solo exhibition of Christenberry’s work called “Passing Time,” and Christenberry arrived shortly after the museum opened at 9 a.m.

“He gave me a personal tour of the show,” Olin said. “We didn’t finish till about noon. He had to tell me a story about every piece that was in there.

“Clearly, he loved his family a great deal,” Olin said. As Christenberry once wrote, “Those things meant something, affected me, and certainly influenced me. In later years this closeness — in the best sense of the word — to family became of tremendous value to me.” And storytelling figured large in their family. Everything he made had a deep well of story tied to it.

The first thing that rose to the surface for Olin was Christenberry’s undeniable affection for the past, for his family, for the place he was from. As Olin told me, he was proud as a peacock to be Southern, from Alabama, and more importantly a Christenberry.

“There wasn’t anybody that was as true to himself and the values that he had as Bill,” Olin said.

“I see a kind of poetry or poignancy in these things that are disappearing,” Christenberry said in 1997. “The South is changing. It’s beginning to look like almost everywhere else.”

Olin liked to think that Christenberry dispensed historical perspective through art as opposed to books. He conveyed powerful sentiments about a place many Southerners, Americans, let alone folks outside of North America did not know nor care to know, and he did so by making something so deeply personal universal.

Olin noted how the places Christenberry photographed were “dying out, going away.” Olin believed Christenberry kept a portion of the South from returning into the earth, from devolving into myth, lore, and superstition.

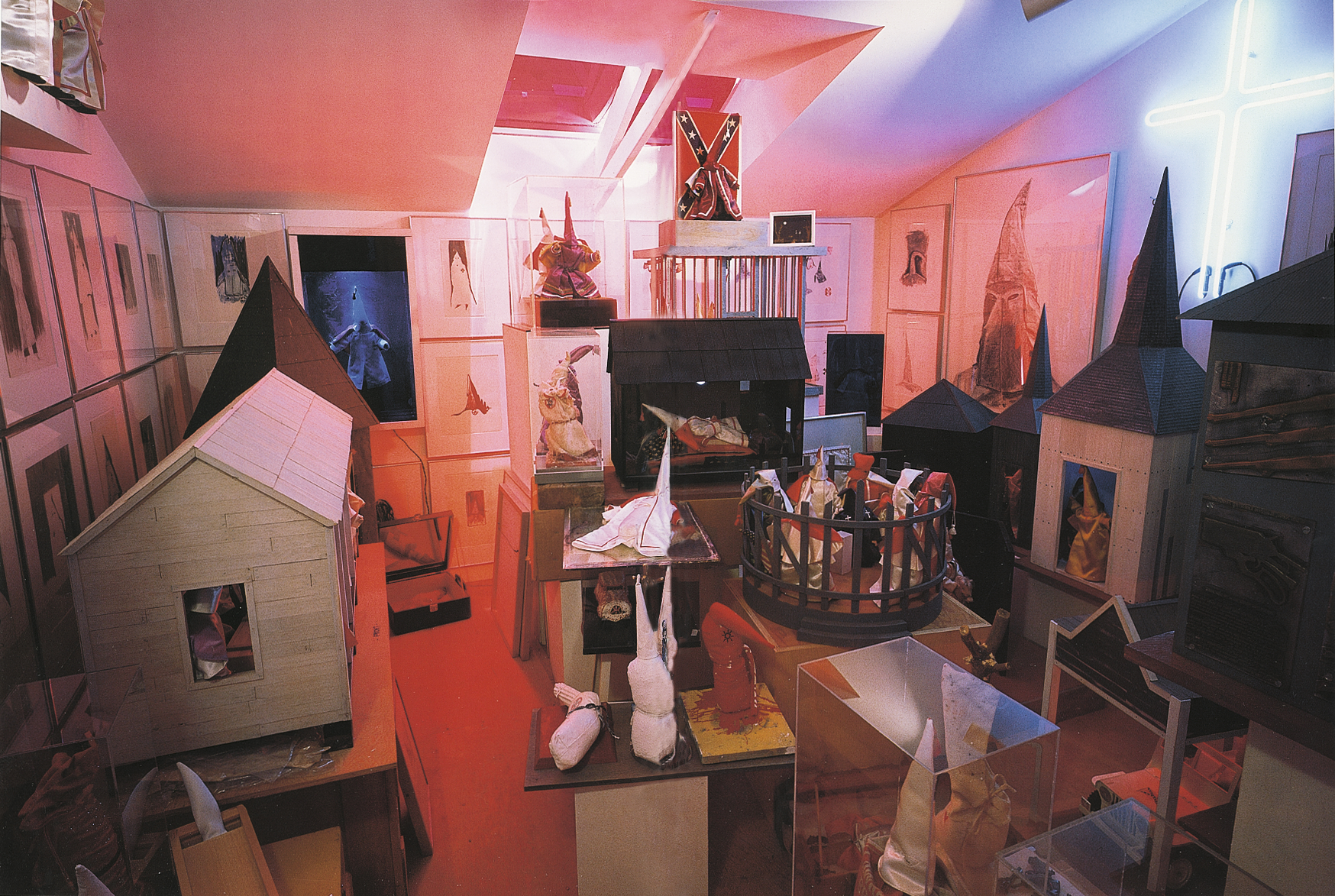

He paused for a while, parsing just how to say it, then spoke of Christenberry’s work that addressed the Ku Klux Klan.

“That sticks out in my mind,” Olin said. That work moved Olin, who believed Christenberry addressed the subject in a distinctly Southern way.

“It was in your face but not in your face,” he said. “He didn’t want anybody to forget.”

In a presentation at George Washington University in 2011, Christenberry stood before an audience showing slides of his work, making jokes that they’d surely get out of there by midnight. And then his hands gripped the lectern, and he explained, “I cannot talk about my work or make an attempt at it without referencing the dark side again.”

A chill seemed to pass through him like a current.

“This is the Klan,” he said.

KKK Sign, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, 1964.

In October of 1960, an ad appeared in the local Tuscaloosa paper for a Klan rally. It was to be held at the Tuscaloosa County Courthouse one evening, and when Christenberry saw the ad, he asked his friend Ed, “Let’s go down and see what this is like.”

Outside the courthouse, all was quiet. There wasn’t anything to suggest a rally was happening, so Christenberry suggested poking around inside where the lights were blaring. Ed told him, “I’m Jewish. I’m not going to go inside with you.”

Christenberry, undeterred, climbed the marble stairs slowly, and he walked inside to find nothing. He made his way up to the next floor and again saw nothing, and then after ascending the third flight of stairs when his eyes could see just above the last step, a Klansman in full robe stood there like a sentry.

“He did not turn and look at me,” Christenberry said. “He looked to the right with his eyes,” faintly visible through the hood’s eye slits towards him. “I ran out of the building. That was the first time I’d ever seen an actual Klansman.”

Soon after, he made his first large-scale drawing of that encounter, a hooded Klansman. For the rest of his life, he would return to the subject, just as he returned to Hale County. He asked, “How could anyone not look at this in some way?”

Installation view of "The Klan Room," 1979.

In 1966, he attended two meetings in Memphis and one in Tuscaloosa where he surreptitiously made photographs of the rallies. Then, more than a decade later “the strangest, most terrifying thing I’ve ever had happen or expect to happen” happened to Christenberry.

In 1979 just down the street from his home in D.C., Christenberry worked in what was a former ballet company, with a smaller room sealed off behind a door. In that smaller room, he’d been working for 18 years on what would become known as “The Klan Room.” Hundreds of drawings, dolls, paintings, and photographs ate up almost every square inch of the space in an installation that showed how deeply haunted he was by the subject. The room lent a form to the “invisible empire” and its depthless hatred. “The Klan Room” attempted to stake out the empire’s edges, to reveal its codes, to show how this was yet one more fearful group trying to preserve their privilege in America.

Just after New Year’s, Christenberry dropped by his studio and noticed something was off — the hinges of the door were askew. Christenberry called Sandy and said, “The Klan Room is gone. Somebody has stolen the Klan Room.” In disbelief, he asked a neighbor upstairs to verify that it was actually gone.

“There wasn’t any vandalism,” Sandy said. Nothing was strewn about, no mess left. They took everything they could and hauled it off, locking the doors behind them. They called the police and filed a report. You can imagine how strange it must have been to describe what the thief (or thieves) stole. “The effect of that theft on my wife and children is difficult to talk about,” Christenberry later said.

The family hired a lawyer, who hired a private investigator, but nothing turned up, not a lead, not even a suspect.

“What scares me the most,” Christenberry later said, “is that it might be somebody I still have contact with.”

“I’m convinced,” Sandy told me. “It’s still locked away some place.”

“Memory is a strange bell, jubilee and knell.”

— Emily Dickinson, in a letter to Elizabeth Holland, 1882

“If you were looking at momma’s house, it would have been to the right,” Teresa Costanzo told me of the pear tree that her first cousin, “Billy,” photographed in Akron, Alabama. At the opening for “Passing Time” at the Smithsonian, she remembered rounding a bend into a hallway where Christenberry’s photographs of the tree in spring and fall faced each other. Two men strode in and were talking “arty” things when she said, “Those are my momma’s pear trees.” The two turned to her in a daze. “I put my hand on my hip and said I bought that pear tree for my momma at K-Mart for $9.99.”

In November of 2017, I drove to where Teresa and her husband, Frank, live on Lake Tuscaloosa. The house was warm and readied for the holidays, and we ran through a whole mess of stories, like the time “Billy” got stuck in a hotel shower, or when he took to the hotel mini-bar without knowing he’d have to pay for it the next morning, or when Teresa introduced her cousin to Samuel “Sambo” Mockbee, the founder of Auburn University’s Rural Studio. But hours into it, Teresa and Frank told me, “He taught us to see beauty in things that other people might not have seen beauty in. He loved Alabama so much. He truly loved Hale County. He saw beauty there.”

“In the South,” Frank said, “things rot and fall apart.” In other places, the downtrodden stuff doesn’t stick around long because it’s unacceptable. He thought Christenberry showed the beauty in age, how things wore over time. “It showed how people lived and survived.”

Green Warehouse, Newbern, Alabama, 1989 and 1991.

Around 2008, just after Working From Memory was published, Christenberry retired from teaching at the Corcoran and returned to Tuscaloosa for a book signing and his birthday. “That was the first time Frank and I realized something was wrong, because he got confused in his lecture and repeated himself,” Teresa said.

“I didn’t want to say anything,” but she spoke with his brother, John, who agreed. “Something’s just not right.”

At first, Sandy thought Christenberry was blowing her off, because he would say something to her then forget he mentioned it. Then, he needed to be reminded where to turn when driving, and he stopped driving altogether soon after.

“I kept waiting for Bill to say something,” Sandy said. “Then one day he did come in from the studio, and he said, ‘Something is wrong. I’m so depressed.’”

William and Sandy Christenberry on the front porch of their home in Washington, D.C., in 2011 (photo by Bill Yates).

In December 2008, doctors diagnosed him with mild cognitive impairment. “It went downhill from then on,” Sandy said, “very slowly but inexorably.”

“His progression was slow, heartbreaking,” Kate said of her father’s decade-long decline. “It was…,” she said, then her voice caught. “It was a drastic change in his demeanor.”

Soon after, Christenberry stopped going into the studio. The camera remained packed up, and the annual trips home ceased.

“No more art,” Sandy said. And as the light fell away at day’s end, he’d become unsettled. “He was loathe to be by himself,” Sandy explained, and the anxiety increased when it grew dark. He “sundowned” as they say, but he was acutely aware of it, open about it, too. He even made fun of it with Teresa. But piece by piece he became more unnerved, and eventually his health followed suit.

In 2011, a urinary tract infection landed him in the hospital. “That set him back,” Andrew said.

The infections became more frequent, and his immune system grew weaker and weaker. His doctors diagnosed him with Alzheimer’s disease in 2012. In 2015, when Sandy was diagnosed with breast cancer, Christenberry moved to a nursing facility just up the road while Sandy underwent treatment.

“It went from difficult to more and more difficult,” Andrew said. “He was confused, fearful, didn’t know where he was. He always had enough mental faculties to know that something was direly wrong, but he couldn’t figure it out. He never turned into one of those people that get to a peaceful place. That was not him.”

“The disease, with its thundering implications, moves in worsening changes to its ungraspable end,” N.R. Kleinfeld wrote in The New York Times of Alzheimer’s and its effect on families. As the shadow of the disease grew it had “no easy parts.” With each day, as loved ones slip deeper into the disease’s “awful mysteries,” family members brush up against their own mortality. The certainty that things are falling apart squares off against the hope things will improve. The sun goes down, and when it rises, it feels like a provocation: The world continues to operate while your family’s life stands still.

Alzheimer’s, like so many incurable and mysterious diseases, stakes the perimeter of what it means to be human — of how everyday life is tied to our capability to recollect it. It seemed doubly heart-rending and cruel that Christenberry’s work, while it could never predict or expect such an awful end, spoke so eloquently to that point when our memories peel away — to that moment when we fail to remember and stop living as we once had.

Just before the first signs appeared in 2006, Christenberry told Philip Gefter, “As I get older, memory becomes a major part of my being.”

William Christenberry’s large-format camera in his studio in October 2018. (Photographs by Michael Adno)

In 2013, Christenberry and his wife Sandy went down to Alabama for the 20th anniversary of the Rural Studio. The day before the anniversary, they went for a ride through Hale County with Teresa and her husband Frank. Christenberry wanted to visit a few places, but “he wasn’t interested in taking any pictures at all,” Sandy remembered. They went down through Akron, to Stewart, and to Five-Mile Cemetery, where he and Teresa’s kin are buried. And finally, they stopped at Guinea Church just off SR 69 north of Havana Junction.

Four decades prior, Christenberry made a photograph of this church. The place sat proudly on cleared ground with a looming pine behind it and a juvenile chinaberry tree beside the entrance. In 1990, he made another photo just after the clapboard structure was doused in a new coat of white paint and the juvenile tree stretched well above the roof. In 2013, the tongue-and-groove was worn, the roof burnt red, and kudzu had swallowed the northern side of the church. Christenberry got out of the car to look at the place but had no interest in making a photograph Sandy said, but with a 35mm camera she’d brought, she took a few frames herself. Teresa and Frank watched as Christenberry and Sandy looked onto the place.

Teresa finished telling me the story, then, after a long pause, said, “That was the last time Billy came to Alabama.”

Guinea Church near Moundville, Alabama. (Photograph by Michael Adno)

“Death is just a moment that ends all the moments that have preceded it. Or so it seems. In reality, it haunts us just as much as the Egyptians. These accumulated disappearances of people we love. We wonder still: Where did they go — anyplace?”

— Andrew Holleran, Chronicle of a Plague, Revisited, 2008

It was a Monday night late in November, about 10 o’clock, when Kate called Andrew.

“Dad has passed,” she said.

Andrew’s first thought, he told me, was “Holy shit, really?!”

“Then,” he said, “it sunk in.”

He left his house, crossed over Rock Creek Park, and met his mom, Emlyn, and Kate at the nursing home. According to the nurses’ aides, they checked on Christenberry around 9 p.m., and when they returned less than an hour later, he’d stopped breathing.

“That’s the way I’d like to believe it happened,” Andrew said.

They looked at his body one last time, and the staff took him away in an ambulance.

In Christenberry’s final days, Andrew explained, nine out of 10 visits went poorly — his father unresponsive, stressed, and worried.

“The visits got tougher and tougher, and he was less and less present every single time.” Andrew had gone to see him three days before his death, on Friday. While “Dad never got to the point where he didn’t know who I was,” Andrew remembered, Christenberry occasionally became confused and called him “John,” which was Christenberry’s brother’s name. Always though, Christenberry would say, “Hi, son” and “Bye, son.”

Two years after losing his father, “it’s gotten better,” Andrew told me. “It’s still painful to think about, but I know I’ve told you about this before: The months leading up to it had gotten so tough that when he did pass and when I got that call from Kate, it was almost an immediate relief for him. He wasn’t suffering anymore. We’d gotten to that point.”

“That stings like a motherfucker,” I said. I knew the feeling. A person leaves, and the world comes to feel vacant, especially when it’s a parent. The air leaves your lungs and something else comes into you, like a tinge of frost.

“It sucks,” Andrew said.

Photographs of Christenberry at his home in Washington, D.C. (Photographs by Michael Adno)

The first entry dates to 1866. There’s the day he bought his first pickup truck. Then, when Robert shot himself in the boys’ room in 1949. When the big oak in the front yard fell. When the first whippoorwill call spilled out of the woods. All these are entries on a 1947 Cardui calendar kept by D.K. Christenberry — Christenberry’s paternal grandfather.

“It’s a wonderful history,” William Christenberry told Terry Gross in 1997, noting the sensitivity bound up in the subjects spanning spring to death.

D.K. kept the calendar tacked to the wall by his bed. Toward the end of his life, when he was bedridden with asthma and a heart condition, he entered dates important to the family. In the yellowed square, hemmed in by red ink, September 5 reads: “1951 D.K. Christenberry died,” in the hand of Christenberry’s father. With it, a tradition formed.

His grandpa left it to one of his daughters, known to Bill as “Aunt Sister,” and in 1973, concerned about its longevity, Christenberry asked if he could inherit it. Aunt Sister happily agreed. Later, he’d take each month and frame it, giving it the title “Calendar Wall for D.K. Christenberry.”

In 2001, he entered his own father’s name. And as he told a crowd in D.C., “It will always be in the family.”

“We talked about that,” Andrew said, “that that would be my responsibility come time.” He, like his father, like his grandfather and great-grandfather, would take pencil to the fragile paper and inscribe the loss of his father.

After Christenberry’s death in 2016, the Mobile Museum of Art showed the calendar in their exhibition, “Christenberry: In Alabama.” So, the family went down a few days early, and there it was. “This is the moment of truth,” Andrew thought.

In the conservation department, a preparator brought down the month of November, removed the stringer, and placed the calendar on the table. Everyone cleared the room, and Andrew sat there looking over the dates.

He’d prepared beforehand, making sure to follow suit in the style of the previous entries. And staring at that medley of paper and ink and memory, Andrew put down, “2016 William Andrew Christenberry Jr. died.”

“I made it through that part pretty good. Then, of course, once I finalized it and took a breath, there it was,” he said. “There was the moment.”

“For my dad,” he explained, “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was on the top tier of things that influenced him, but I know that as far as an artifact of family history, the calendar was front and center.”

“It’s in the same vein. It’s a story. You could read it like a poem.”

* * *“When we went down for the funeral,” Andrew remembered, “I’d been thinking a lot about burial vs. cremation, because my wife, Julie, had lost her mom about two years before, and she was cremated. So, it made me think: What do I want? And where I’m headed with that is just thinking about those two options and how, for my dad, it just seemed absolutely perfect for him to be back in Alabama red earth — to be put in that ground.”

At the funeral in Tuscaloosa, Christenberry was buried next to his mother and father, and one thing stuck with Andrew: It was the red earth so ubiquitous to that part of Alabama, so dear to his father. It was all around them. Between two hummingbirds on his tombstone, the inscription reads, “Memory is a strange bell, jubilee and knell.”

Just as they were about to lower the casket, Andrew thought of the circle his father had made in his own life — the circle Andrew was making himself. Around the grave, heaps of red earth sat piled up.

“We grabbed a couple handfuls of it and put it on the casket before we left.”

In that moment, Andrew thought, “That’s where he belongs.”

Near Stewart, Alabama, 2017. (Photography by Michael Adno)

Epilogue

In the spirit of this piece, I’d like to thank the people who made it possible. Thank you to Sandy, Emlyn, Andrew, and Kate Christenberry for opening their home and in turn affording us this story. Thanks to Teresa and Frank Costanzo, Robert Olin, and Sonny Ryan for devoting their time and care to this piece so generously. I need to, of course, thank Chuck Reece for giving this story a readership along with the entire team that makes this magazine possible. I’d like to make special note of the innumerable people whose work this story was built upon but especially Susanne Lange, Richard J. Gruber, and Thomas Southall. At Hemphill Fine Arts, Pace/MacGill Gallery, and Fundación MAPFRE, who helped assemble all the photographs for this piece, thank you Mary Early, Caitlin Berry, Lauren Panzo, Jessica Mostow, and Paloma Catellanos as well as Jonathan Eaker at the Library of Congress. Most importantly thank you to William Christenberry for showing us the beauty bound up in place and our relationship to it.

Michael Adno is a writer and photographer from Florida. He last wrote for The Bitter Southerner about David Wolkowksy, the man who lent Key West its sense of style in “This Man Is an Island,” and previously “The Short & Brilliant Life of Ernest Matthew Mickler.”

All photographs by William Christenberry courtesy of the Christenberry family, unless otherwise noted. Header image: Christenberry’s China Grove Church, Hale County, Alabama, 1979.