Next month, the Nashville Ballet opens a new production of Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire,” and we will see more than his sad, broken heroine. We’ll also see what made her that way.

“As silent as a mirror is believed

Realities plunge in silence by…

I am not ready for repentance;

Nor to match regrets. For the moth

Bends no more than the still

Imploring flame.

And tremorous

In the white falling flakes

Kisses are, —

The only worth all granting.”

— from “Legend,” by Hart Crane

the 1940s, when Mississippi-born Tennessee Williams sat down to pen A Streetcar Named Desire, the state of Louisiana defined rape as “the act of sexual intercourse with a female person not the wife of, or judicially separated from the bed and board from, the offender, committed without her lawful consent.” Spousal rape wasn’t even recognized by law, and a lady better be able to prove that she put up “a genuine and bona fide resistance” if she were ever to have a shot at being believed. It wasn’t unusual in those days for a husband to smack his wife around at the dinner table, maybe pop her one for talking back, and he still expected his laundry done and lunch packed every day.

A woman’s purity was her primary currency in the South Williams knew and wrote about. Marriage, contingent on the perception of that purity, meant survival. A single woman was suspect.

This was the cultural context in which the playwright drew the seminal Blanche DuBois, frenetic and feather-light, the sad Southern belle who finds herself stepping off of the Desire streetcar, no job and no husband, one steamer trunk to her name, into Louisiana’s languid, humid heat. Into the dilapidated home of her sister, Stella, and brutish brother-in-law, Stanley.

Williams sets the scene for us: “…an atmosphere of decay. You can almost feel the warm breath of the brown river beyond the river warehouses with their faint redolences of bananas and coffee. A corresponding air is evoked by the music of Negro entertainers at a barroom around the corner.”

Against this backdrop of decay, the soundtrack of jazz that Williams refers to as “blue piano,” Streetcar shines a light on its weighted themes – alcoholism, mental illness, and what it means to be a Southern woman. He draws them out on a thread of tension inside Stella and Stanley’s small, suffocating New Orleans apartment, where Stanley is the reigning monarch inside its few tiny rooms. Here, he terrorizes Blanche, hits his wife, and demands her fealty. Stella stays with him, of course, chooses him even after Blanche tries to tell Stella that Stanley raped her, because to admit the truth, to believe Blanche, would mean to risk her own safe place in a dangerous world made for men.

Blanche is Williams’ moth in the midst of all this violence — frenzied, fluttering, and frail, the relic of a bygone South. At best, Streetcar’s 20th century audiences saw Blanche as a victim, timidly and dangerously drawn to the flare of desire, to the beds and the booze that destroy her in the end.

A Streetcar Named Desire is an iconic story most folks think they know well, likely thanks to some assigned high school reading and a sweltering performance by Marlon Brando as Stanley in the 1951 film by Elia Kazan.

But in 2012, international choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa and London-based theater director Nancy Meckler decided to challenge that notion, coming together to turn Williams’ classic Southern play into a Scottish ballet.

Choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa

“I think the thing is, when you’re trying to think of what would make a good ballet story, [Streetcar] made a lot of sense,” says Meckler. “There are these wonderful characters that the audience can connect with very quickly. You’re looking for drama. You’re looking for emotional depth. But you’re also looking for something that people can connect to.”

The audiences of the ’40s and ’50s, and even those of later stage and screen performances, didn’t exactly connect with Blanche, though. They saw her as a liar and a loose woman, an alcoholic slowly unhinging herself from reality who couldn’t keep a man and ultimately got what was coming to her — an implied sexual assault and one-way ticket to a mental institution.

What Meckler and Ochoa did by turning Streetcar into a ballet was ask us to look at Blanche again, to see this archetypal Southern woman anew, and maybe this time find a few flecks of ourselves in her flickering light.

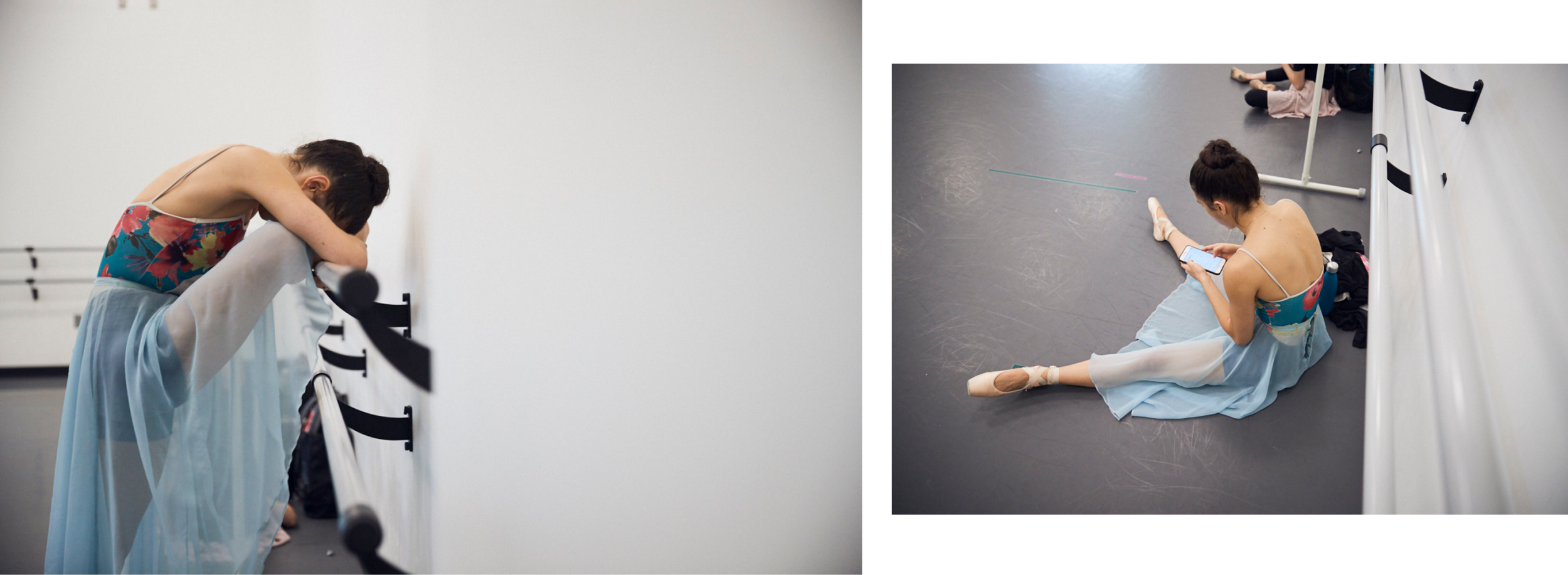

Dancers Julia Eisen and Michael Burfield rehearse the roles of Blanche Dubois and her husband, Allan Grey, at the Nashville Ballet studios.

Since its creation in 2012, Meckler and Ochoa’s ballet was performed frequently by the Scottish Ballet and the Estonian National Ballet, which toured its production across Europe and in three American cities, Los Angeles, Washington, and New Orleans. Now, Meckler and Ochoa are bringing a new production to the South. Danced by the Nashville Ballet at the Tennessee Performing Arts Center, the production opening November 1 will mark the first time the Streetcar ballet has been performed by an American company or a Southern ballet company — and the first time a Southern woman will dance the role of Blanche.

In previous performances, Meckler says, the audience had to imagine an atmosphere. But not so in Tennessee, says the Nashville Ballet’s artistic director, Paul Vasterling.

“I do think Southerners understand [the story] a lot better than other people,” he says, “because you kind of … you understand the weather, what it felt like, what it feels like in the summer [here]. And the sort of eccentricity that exists [here] as well, and how Blanche might’ve fit into that.”

Indeed, as universal as Williams is, the Nashville audience won’t have to use their imaginations to create some far-flung locale, like a Scottish or Estonian audience might, in trying to conjure up New Orleans. They won’t have to create from nothing a humid Southern city painted thick with heat and music, won’t have to imagine a woman like Blanche.

All they’ll need to do is think back. Remember.

It’d be a fair question to ask how Ochoa and Meckler could manage to translate some of the most famous dialogue in the history of American theater into mute movements. And how dance could be a viable platform for the translation of a spoken story with lines that so many have memorized by heart.

Not to mention the issue of chronology.

So much of what we learn about Blanche in Williams’ play is told through recollection, through secondhand accounts of the past, through memory. But as Ochoa notes, “There is no past tense in an arabesque.”

Thankfully, Ochoa and Meckler excel at what they do, and find some truly beautiful workarounds — including telling Blanche’s story from its very beginning in Mississippi rather than from her arrival in Louisiana — that not only solve the issue of narrative structure, but also create space in which the audience is finally able to develop the empathy that Blanche is owed.

“One of the major things that we did was that we show the audience all of the backstory of Blanche DuBois,” Meckler says. “Whereas, when people see the play, they only hear her talk about her past, and I’m not even sure whether they believe her.”

Indeed, Blanche is a most unreliable narrator because she recalls her experiences through the tinted lenses of alcoholism and trauma, the former of which causes the audience to see her almost as a caricature of herself. And Blanche does lie, admits she lies, but she lies as much to herself as to Stella and Stanley and Mitch - Stanley’s friend in the play, and Blanche’s very temporary love interest. Blanche knows her survival is contingent on the maintenance of her image as a proper Southern woman, and the truth of her experience is far from the image’s tenets of purity and chastity.

Rather than highlighting Blanche’s gossamer sense of reality, though, Meckler says she and Ochoa took her “very seriously.” They do what Stella and Stanley and Mitch won’t do. They believe Blanche. They centralize Blanche and her story, and allow her to show the audience that story from beginning to end. And in doing so, they also contextualize her mistruths.

Giving the story back to Blanche was one of the biggest factors — along with staging an entirely female-led production — in Vasterling’s decision to bring the Streetcar ballet to Nashville.

“I wanted to do the story because I love the way it was done. It was directed and choreographed by two women,” he says. “And Annabelle and Nancy took the story, and told it through the lens of Blanche. I love this female perspective and lens through which the story is told, taking the classic Tennessee Williams and sort of shifting it slightly so we see it through different eyes.”

Showing Streetcar from its chronological, rather than narrative, beginning not only “helped people to follow the story,” says Ochoa, “but also to feel empathy and understand the characters.”

Including the backstory of Blanche and Allan's courtship and marriage was a critical change made by international choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa and London-based theater director Nancy Meckler for their balletic retelling of “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

In Meckler and Ochoa’s version, the audience gets to see a young, happy Blanche falling in love with and marrying her husband, Allan Grey — something the play only alludes to. They also get to watch Blanche as she discovers Allan’s affair with another man, her subsequent disgust, and the pain and anger with which she turns him away. Allan’s suicide as a result of Blanche’s discovery gets particular attention. It’s one of the truly defining moments in Blanche’s life. Blanche blames herself completely for Allan’s self-destruction; it is an event, as we see in the play and in the ballet, she never truly recovers from. And the ballet finally gives Allan’s death the gravity it deserves.

The audience sees Blanche’s homeplace, the antebellum Belle Reve, as it literally falls into ruin after the death of her family – “funerals are much prettier than deaths,” she tells us – and we find her next in that sordid hotel, soaked in grief and liquor and men.

It’s only then, after the truth of her tragic past is revealed to us in its entirety, that the ballet picks up with Blanche’s arrival in New Orleans, on Stella and Stanley’s doorstep. And by then, the ballet’s audience has gained a bit of distance from the neurotic mess of a woman they find on Williams’ pages.

Williams didn’t intend to create a character his audience would disdain, according to Meckler. He likely sympathized with her — some say that Williams modeled Blanche after his own sister, who struggled profoundly with mental illness and underwent a lobotomy. Others say Blanche was a projection of the playwright himself. Either way, Meckler says, Brando’s casting in the landmark film interfered with audience sympathies.

“I think Williams wanted you to feel empathy for her,” she says. "It’s just that, particularly because Marlon Brando was so unbelievably attractive as Stanley Kowalski, everybody really wanted to fall in love with Stanley. They think [Blanche] is a pain in the neck. But the reality is, Stanley rapes Blanche, and he beats up his wife. It’s played down on stage because you weren’t actually allowed to show that on stage in those days. You weren’t allowed to see a man beating up his wife, or even admit that it was happening. Nor were you allowed to see a rape on stage. And so that was played down. And in the film, once again, it’s lightly glossed over.”

But Meckler and Ochoa don’t allow their audience to look away.

“In order to understand the role of Blanche, you have to understand her wounds,” Ochoa says. “Otherwise, you can quickly think, ‘that’s her fault.’”

Ochoa and Meckler instead remain compassionate and curious about Blanche. In dancing her backstory, they interrogate her circumstances within the context of their time, considering what it really meant to be a woman of a certain age in that geographical place in the 1940s — a woman who knew her youth and beauty were fading, and believed the only chance she had of surviving was finding a man to protect and save her.

“She does everything to be loved,” says Ochoa, and she and Meckler continue to ask the audience, scene after scene, to remember that. To see themselves in Blanche and consider what they might do, might have done, to face the ravages of loss and grief.

Theater actress Rosemary Harris, who played Blanche in a 1973 Lincoln Center production of Streetcar, was quoted in an NPR article as saying Blanche “was the loneliest part I ever played on the stage.”

“Most people,” Harris said, “even if they’re unsympathetic characters like Lady Macbeth … at least she has … Macbeth rooting for her. But there is nobody rooting for Blanche. And you go through that night after night, and it begins to get to you. It’s very, very lonely up there.”

Nashville Ballet’s Julia Eisen, who will dance the principal role of Blanche, says she can relate.

“Honestly, no one understands unless you’ve played Blanche,” says Eisen. “So I completely understand. I also heard about an actress who went crazy, she had a real panic attack on stage because she felt so connected to Blanche. It’s lonely. It’s a very hard role to play.”

It’s also a very hard role to put down, take off.

“I pride myself as a dancer,” Eisen says. “I come into the studio, do my job, and then I’m really good at being like, ‘okay, I’m not going to take it home with me.’ But with Blanche, it’s really difficult to not take that home.”

Eisen studied the play, the film, the Streetcar ballets performed by other companies to begin learning how to inhabit such an all-encompassing role. Countless actresses, and now several dancers, have tackled the part, but the Blanche that Eisen discovered was her own.

Dancing Blanche DuBois is both physically and emotionally taxing for Eisen, who's on stage for all but two scenes of the two-hour ballet.

Eisen, who grew up in North Carolina, lived in Richmond, Virginia, and has been in Tennessee for the past decade, will dance Blanche, for the first time, from the unique perspective of a Southern woman. As critically acclaimed as their performances were, it’s a perspective even monolithic actresses like Jessica Tandy and Vivian Leigh perhaps didn’t, and couldn’t, have.

“I feel like Blanche is completely vulnerable. I think she’s kind of tragic,” Eisen says. “But I also think she’s complex and misunderstood. I feel that she’s somebody that has so many layers to her. She’s more like a rose petal at the very end of a rose. She just wants to be pure and loved.

“To play this Southern woman is so real to me, because I see her all the time. Blanche is really not far off from the women I grew up with. The women I looked up to. My teachers, my neighbors … I’m not [someone from outside the South] playing a Southern girl. I am a Southern girl.”

That’s obviously not to say a talented performer from anywhere couldn’t excel in the role — that’s an idea antithetical to what good and powerful art is able to do. But it is to say that if we can’t hear Blanche speaking to us in the ballet, it’s helpful — and beautiful and powerful — to see Blanche embodied by someone who understands intimately where she comes from.

There is something almost mythic in watching Blanche’s story unfold without words.

In the ballet, Blanche’s literal silence is haunting, but it’s also another avenue through which the audience is better able to insert itself into her point of view. Hearing Vivian Leigh’s quivering voice on screen makes it harder to sympathize with her — it’s ceaselessly fraught, breathless. Her relentless need, childlike. And as a result, the audience takes her, and her wounds, as seriously as they would a child’s.

But telling the Streetcar story through ballet lends Blanche a dignity and grace previously denied her. It also makes way for a different level of understanding of the characters.

“Dance, in a way, can open up the work to bigger, to one’s own, interpretations a lot easier,” says Vasterling. “You’ll see it in a different way. You’ll understand it in a different way. And sometimes the understanding that you get is visceral. It’s not intellectual; it’s visceral.”

Such, he says, is the magic of movement. “The steps, the movements, are the words.”

Recently, says Vasterling, the Nashville Ballet has worked more carefully and intentionally to choose productions that connect with a contemporary audience and make sense within our current news cycle.

“What we’ve been doing around here lately, a lot, is delving deeper into what we do,” he says, “into the stories that we tell. We’re being more cognizant of how they are resonant now.”

Eisen says the ballet allows audience members to look at Blanche DuBois differently than we do in the stage play or movie: “We don't want to look in the mirror and be like, ‘That could be me.’ It’s heavy. It’s hard. But I think it’s so important, and I'm so honored to be able to do this.”

A Streetcar Named Desire may have debuted in 1947, and indeed much has changed in the world since then — modern audiences likely find Blanche’s homophobia both ignorant and archaic, for example — but most of the themes with which the play contends are still playing out in women’s lives every day.

“I asked Annabelle when she was here last time,” says Vasterling, “I said, ‘Tell me what do you think of this story? What is it about [to you]?’ And immediately she said, ‘Well, it’s about slut-shaming.’ It’s about how this woman is treated because she doesn’t fit into this mold, the mold that Stella fits into. She’s outside of the mold, and she is basically abused for that, both individually and societally. A man would not be treated the same way in this period, or even now.”

Indeed, it’s not hard to connect Blanche’s abuse at the hands of both Mitch and Stanley to the women of the #MeToo era, women who are still fighting to be believed in boardrooms, breakrooms, and bedrooms all across this country. And women are still painfully aware of the ways in which society views our outward physical appearance as a barometer for our inherent value — something Blanche knew all too well.

That was perhaps Meckler and Ochoa’s point all along. Not that their balletic retelling of Williams’ tale is a simple and lovely reminder of times gone by. But that it is a mirror, even after all this time, of where we still are, in many ways, right now.

That Blanche herself is a mirror, a fluttering, reflective light, for those brave enough to look at her.