Some folks know Zora Neale Hurston was a giant of American literature, but many have never read her work ... or even heard her name. Michael Adno retraces the footsteps of Hurston and interviews those, like Alice Walker and Valerie Boyd, who followed her — to remind us all Zora was maybe the most important American writer to have ever lived.

“I know that the earth absorbs perfume and urine with the same indifference.”

— Zora Neale Hurston

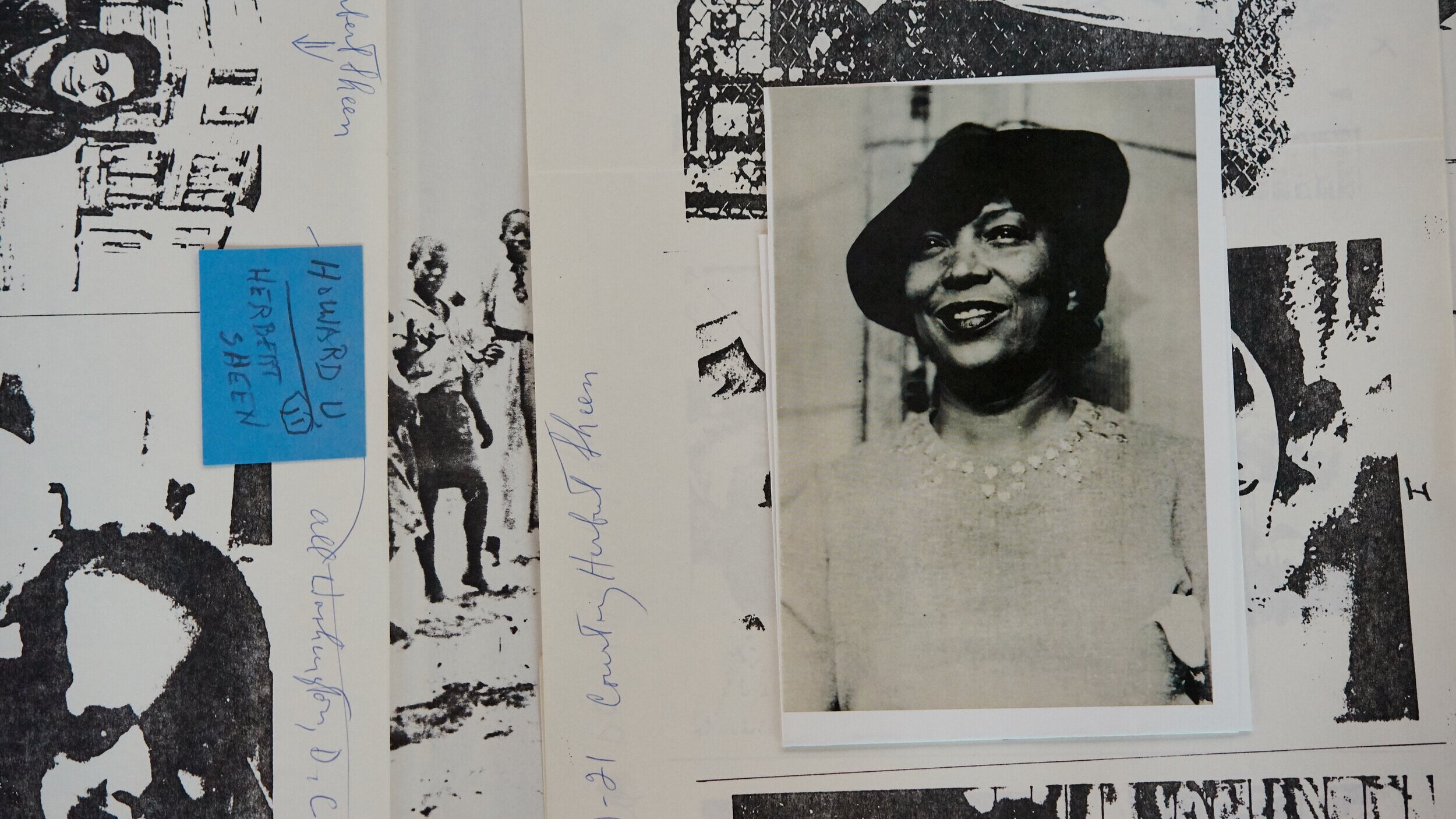

Portrait of Zora Neale Hurston by Carl Van Vechten in 1938, Courtesy of the University of Florida

Myths ferried Zora Neale Hurston through life. And long after her death in 1960, they coursed through her work like a stream. But at times, it seemed those very myths hung over her like a constellation made up of stars she’d arranged herself.

Time, a lifelong enemy of Hurston’s, reached her on January 28, 1960, when she died of a stroke in Fort Pierce, Florida — a tiny town bisected by the Indian River 120 miles north of Miami. On February 4, 1960, the Associated Press ran her obituary. It read, “Zora Neale Hurston, author, died in obscurity and poverty.” And with those words, syndicated in The New York Times and in papers from Jamaica to California, a new set of myths formed. Some listed her age at 57, others 58. After all, depending on what suited her, she told people she was born in 1901, 1902, or 1903 — in Eatonville, Florida.

But as it turned out, none of this was true.

“It seems to me that organized creeds are collections of words around a wish. I feel no need for such. I know that nothing is destructible; things merely change forms. When the consciousness we know as life ceases, I know that I shall still be part and parcel of the world.”

— Zora Neale Hurston, Mules and Men, 1935

It was Sunday afternoon, February 7, when six pallbearers carried Hurston’s body out of the Peek Funeral Chapel. The hearse turned west out of the drive, pushed down Avenue D nine blocks before hooking north onto 17th Street and following it to where it fell off into Taylor Creek, passing columns of mango and guava trees, hedges of ixora and bundles of palmetto.

At the end of the road, nine flower girls led the way into the Genesee Memorial Gardens Cemetery, where Hurston was interred that evening. While Hurston died without much to her name and with debts unpaid, her friends raised the money to lay her to rest. Her friend, Marjorie Silver, wrote a piece in the Miami Herald, explaining the need to raise money for the funeral, and in turn, a slow drip of donations arrived piece by piece from all over America.

Her publishers, J.B. Lippincott and Scribner’s, sent $100 each. Her friends Fannie Hurst and Carl Van Vechten did, too. Her colleagues went door to door. The funeral home donated the casket, and the cemetery waived the burial fee. The students of Lincoln Park Academy, where Hurston was a substitute teacher, held a benefit concert. The principal, Leroy Floyd Sr., was a pallbearer. All nine flower girls were students. Margaret Paige, an administrative assistant, made the arrangements. In total, $661.87 came to the fore, the equivalent of nearly $6,000 today.

As the crowd hemmed in the grave, her editor at the Fort Pierce Chronicle, C.E. Bolen, spoke. He noted how she didn’t care for anyone’s perception of her. He pointed to her tenacity, her ability to deliver.

“She didn’t come to you empty,” he said.

Two pastors spoke that evening, one Baptist, one Methodist. Rev. Wayman A. Jennings of St. Paul AME explained how the newspapers described her as poor when she died, but he believed the hundred-plus people standing there suggested otherwise.

“They said she couldn’t become a writer recognized by the world, but she did it,” he said in his eulogy. “The Miami paper said she died poor, but she died rich. She did something.”

The Lincoln Park Academy choir sang “Just a Closer Walk with Thee” as the light softened.

After everyone left that evening, the sun fell away over the Gulf of Mexico. Spring turned to summer, and the rains came. Years passed. The bluestem and muhly grass grew thick, and because the grave bore no marker and the cemetery was left unattended, Hurston’s grave disappeared. Beneath the tall grass and span of time, Hurston’s legacy grew dim; a catalog of myths grew like weeds all around her.

Her first biographer, Robert Hemenway, wrote in 1977, “Why did her body lie in wait for subscriptions to pay for a funeral? The answers are as simple and as complicated as her art, as paradoxical as her person, as simple as the fact that she lived in a country that fails to honor its black artists.”

From left: A typescript of Hurston’s work for the Florida Writer’s Project, Hurston at a Turpentine Camp in Cross City, Florida photographed by Robert Cook, an author portrait of Hurston in 1948, offerings left at her grave, and a collage cut-out belonging to Stetson Kennedy, Courtesy of the University of Florida

The woman who in her lifetime published four novels, two collections of folklore, an autobiography, and nine plays, who garnered two Guggenheim fellowships, grew pale with each passing year. In her lifetime, she won the faith of Franz Boas and Langston Hughes, of Alan Lomax and Stetson Kennedy, of Fannie Hurst and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings — of cowboys and politicians, migrant workers and doctors, of Vodun priests and strangers. She became one of the most celebrated figures of the Harlem Renaissance and later a literary lodestar for Alice Walker, Maya Angelou, and Toni Morrison, a precursor to Paule Marshall, Edwidge Danticat, and Jamaica Kincaid.

In 1961, her friend, Theodore Pratt, wrote a tribute in the Florida Historical Quarterly. “She is out of circulation and all her books are out of print,” he wrote, “One cannot be rectified. The other should be.”

Thirteen years later, a young writer from Eatonton, Georgia, would set down in Florida to see about that.

“There is enough self-love in that one book — love of community, culture, traditions — to restore a world. Or create a new one.”

— Alice Walker on Their Eyes Were Watching God, from the 1979 dedication of the Walker-edited Zora Neale Hurston reader, I Love Myself When I Am Laughing and Then Again When I Am Looking Mean & Impressive

It was August 1973 when Alice Walker arrived in Sanford, Florida, looking for Zora Neale Hurston. From the plane, she looked down on the pattern of lakes bleeding into the nearby woods, the trees glowing green.

For weeks before, Walker had corresponded with Charlotte Hunt, another Hurston scholar, swapping kernels of lore that assembled some picture of Hurston’s life, and later in her 1975 essay for Ms. Magazine, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” Walker recounted that trip to Florida.

When Walker came out of the terminal in Sanford, Hunt, who at the time was working on a graduate dissertation on Hurston, met her there, and they set off for Eatonville — the place where Hurston grew up. It was the place that would form the covalent bond of her novels, folklore, and anthropology. It was a place Hurston described as “a city of five lakes, three croquet courts, three-hundred brown skins, three-hundred good swimmers, plenty of guava, two schools, and no jailhouse.”

A mural along Kennedy Blvd in Eatonville depicts Zora and her work among other African-American luminaries

Twenty minutes out from baggage claim, the two walked into Eatonville’s City Hall armed with what Walker deemed a “simple, but I feel profoundly useful lie.”

“I am Miss Hurston’s niece,” she told the young woman sitting behind a desk strewn with letters.

The woman thought Walker and Hunt might like to see about Mathilda Moseley — a lady in town old enough to have known Hurston. Walker knew the name from Hurston’s books, but to learn that the character was not only real but alive became the first meaningful line of inquiry in her own search for Hurston.

After the two tracked Moseley down in her driveway, Walker set to gaining her trust and uncovering any morsel about Hurston and the Eatonville of her lifetime. Once Walker mentioned Moseley’s hibiscus bushes, along the edge of the drive, Moseley softened, and a wealth of story followed.

She asked Moseley, “Why is it that 13 years after Zora’s death, no marker has been put on her grave?”

“The reason she doesn’t have a stone is because she wasn’t buried here,” Moseley said. “She was buried down in South Florida somewhere. I don’t think anybody really knew where she was.”

A week later when Walker and Hunt pulled up to the Lee-Peek mortuary in Fort Pierce, the sight was ghastly. The building almost sunk into itself under the weight of old age. Inside, Walker described the bathroom where a bottle of black hair dye dripped ominously into the sink, two pine coffins resting in the bathtub.

“As I told you over the phone,” Walker said to Sarah Peek Patterson, “I’m Zora Neale Hurston’s niece, and I would like to have a marker put on her grave. You said, when I called you last week, that you could tell me where the grave is.”

At that point, she was Hurston’s niece, because, like she wrote, “as far as I’m concerned, she is my aunt — and that of all black people as well.”

Patterson explained how Hurston was buried in 1960, in an old cemetery off 17th Street, when her father still ran the place. She gave Walker the coordinates, explaining she knew where Hurston was buried — right in the middle, actually.

“Hers is the only grave in that circle — because people don’t bury in that cemetery anymore,” Patterson said.

Before they left, Patterson sent a woman named Rosalee with them to help them find the plot. And in the punishing heat of late summer when breezes are sparse and humidity blankets the state like a duvet, the three women set out for the Garden of Heavenly Rest, looking for a ghost.

In her hand, Walker looked over the drawing Patterson gave her. In it, a circle staked out the edge of the cemetery that appeared quite small, but when they stood at the entrance, the circle grew to the size of an acre. Through the gate flanked by stone elliptical walls, the three stood at the edge of what was an overgrown, seemingly abandoned field.

The neglect stung.

Hurston’s grave in Fort Pierce in August this year

Walker and Rosalee trudged into the tall grass, and a few paces in, Walker called to Hunt, “Aren’t you coming?”

“No,” she shouted, “I’m from these parts and I know what’s out there.” That was to say snakes were out there — any variety of pygmies, diamondbacks, canebrakes, or possibly a cottonmouth along the creek, maybe even a coral snake.

“Shit,” Walker mumbled to herself and put one foot in front of the other as Rosalee followed suit.

Step by step, the two edged toward the center, using the entrances as equidistant markers to determine where the center ultimately could be. Hopeless could quickly molt into masochistic, and Walker knew that. The sun didn’t help.

As her sense of hope grew dim, Walker resorted to what she felt was the only thing to do: “Zora!” she yelled as loud as she could, sending Rosalee into the air. “Are you out here?”

When Rosalee’s feet returned to the ground, she said, “If she is, I sure hope she don’t answer you. If she do, I’m gone.”

Again, Walker shouted, “Zora! I’m here. Are you?”

“If she is,” Rosalee growled, “I hope she’ll keep it to herself.”

Again, a call without response, and finally, Walker laid it bare: “I hope you don’t think I’m going to stand out here all day, with these snakes watching me and these ants having a field day. In fact, I’m going to call you just one or two more times.”

With that promise, Walker bellowed one last time, “Zo-ra!” She took one more step, and then, her foot dropped into a sunken rectangle, six feet by three feet, giving off the impression of a grave.

The two looked around a bit more to confirm there weren’t any others nearby. Walker told Rosalee she didn’t have to continue, but Rosalee said, “Naw, I feels sorry for you. If one of these snakes got ahold of you out here by yourself I’d feel real bad.”

“Thank you, Rosalee,” Walker said. “Zora thanks you, too.”

“Just as long as she doesn’t tell me in person,” Rosalee said as they retraced their steps to the road.

Afterward, Walker and Hunt headed east toward the river to see about a stone. At Merritt Monument Company, Walker set her eyes on a tall black slab, one she felt mirrored Hurston’s spirit. The woman helping her said, “That’s our finest. That’s ebony mist.” The price was exorbitant, so she settled for another, followed the engraver inside and handed him the epitaph she wanted incised in stone. It read:

ZORA NEALE HURSTON

“A GENIUS OF THE SOUTH”

1901 - - - 1960

NOVELIST FOLKLORIST

ANTHROPOLOGIST

They went back once more and marked the spot with a flag before heading home.

After Walker’s pilgrimage, a resurgence followed. The first biography of Zora Neale Hurston, by Robert Hemenway, would arrive on bookshelves across America in 1977. The Zora! Festival in Eatonville began in 1989. In 2003, Valerie Boyd’s Wrapped in Rainbows became the second biography of Hurston. In 2007, Deborah Plant would publish another, “A Biography of the Spirit.” And since 1975, more than a dozen posthumous collections have come out. Just last year, Hurston’s manuscript Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo”, written between 1927 and 1931, was finally published.

A decade after she found Hurston’s grave, Walker became the first African American woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, with her novel The Color Purple, which also won the National Book Award. When she published her essay about Hurston in 1975, only four of Hurston’s books were in print. Today, Their Eyes Were Watching God has become one of the most assigned books in American colleges and remains a waypoint on the arc of American literature — Hurston’s career something like a constellation.

Smoke crept up over the low-slung block homes along School Court when Deputy Patrick Duval passed by. With no clouds, he could see the signal from miles away. Once he edged closer, he saw it was Hurston’s home.

Duval knew Hurston.

“I knew who she was and why she was important,” Duval told the Palm Beach Post in 2010, but he also knew her personally. When he got to the back of the house, he saw a man cloaked in smoke. Inside an oil drum, Hurston’s manuscripts, letters, and belongings were dissolving into ash. Duval ran to the spigot and extinguished what would have been an irrevocable loss.

In a chest beside the drum were the rest of her papers, and so Duval took the papers, burnt and waterlogged, to Dr. Clem Benton, the owner of the home. And with Marjorie Silver and Hurston’s family, Duval made sure the papers found their way to the University of Florida in 1961, which was Hurston’s intended destination for them. Over the next two decades, curators carefully reconstructed the manuscript of Hurston’s last book, Herod the Great. They took the names on the envelopes and began to assemble the last years of Hurston’s life, acquiring a cache of correspondence that would eventually fill 14 boxes within the collection in Gainesville. In 1970, Robert Hemenway passed through the doors of the library to build out the bones of what would become the first biography of Hurston, consulting the only personal journal belonging to her that was ever found.

Zora Neale Hurston (center) speaks with two women while reporting an assignment for the Miami Herald on migrant workers. This is the last known photograph of Hurston in the late 1950s, saved by Patrick Duval. Photograph by Ernie Tyner, Courtesy the University of Florida

To Florence Turcotte, the literary manuscripts curator, Duval was nothing short of a superhero, a character fit for a Hurston novel himself.

“That’s why I tell the story every chance I get,” she said. In the Grand Reading Room, 12 slender tables lined with lamps stretch into a hall with vaulted ceilings where wooden bookcases stand testament to the deep well of Floridian writers, artists, and history. On the tables, researchers pore over the collection piece by piece, but no collection is consulted more often than the Hurston papers.

“It’s tantalizingly incomplete,” Turcotte said. “It’s the remnants of her life. It’s what was left when her books were out of print, when she was broke, when her health was lousy.” But in those papers, there’s no air of melancholy or somber tone. Instead, Turcotted sensed hope.

“Her connection with people, whether imagined or real, comes through in that writing,” Turcotte said of Hurston’s letters. “She made people feel like she cared what was coming out their mouth. She knew exactly what to say to people.” Turcotte imagined those friendships were in some ways all Hurston had toward the end of her life.

As to the myths, she felt like Hurston blurred her hagiography intentionally. It was a means to ensure only Hurston’s hands touched it. When she was born, where she was born, that belonged to Hurston.

The more people’s lips that story graced, the truer it became.

“The veracity grows. It doesn’t matter if it’s true,” Turcotte said. “It’s part of the oral tradition.”

In the stacks, Florence Turcotte flips through the only personal journal ever found belonging to Hurston, which is known among the curators as the “sketchbook”

Kevin Young, the poet and director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, felt it was something bound up in her bones. In his book, The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness, Young writes at length about Hurston and about lying as a kind of improvisation inextricably tied to black culture.

“She’s invested in the black tradition of folktales,” he told me. This was a tradition that reached back in America to 1619 when the first slaves arrived in Virginia, WHO then created their own oral tradition of stories that imagined a more just future. “That’s where she came from. But it was also a way of combating the racism and sexism she encountered in spades. I think it was strategic and fascinating.”

“She’s not alone in that tradition,” he said.

When you look through her work, specifically Mules and Men, you see it — lies in exchange for truth, masks that reveal more than they hide, little tales that fasten down the spirit of something bigger. Ultimately, she told countless others lies in service of the truth.

And so for decades after her death, any answers about Hurston only generated more questions. As she wrote in her 1941 autobiography, “This is all hear-say.”

That was the first sentence of the third chapter, “I Get Born.” In it, she writes, “Maybe, some of the details of my birth as told me might be a little inaccurate, but it is pretty well established that I really did get born.” She was the fifth of nine children, the second daughter to John and Lucy Hurston. But as the story goes: On the day her mama’s water broke, nobody was around. John was gone on business. Everyone else at a hog-killing. The midwife, Aunt Judy, was more than a mile away in a neighboring town.

“My mother had to make it alone,” Hurston wrote.

Then came a sound from the yard, “Hello, there! Call your dogs!” It was a man, who knew the family, and from inside he could hear the cries. He pushed past the barking dogs, pried the door open and found Lucy Hurston on the floor with her baby. The man cut the umbilical cord, lit the stove, and an hour later when the midwife arrived, Lucy Hurston held Zora in her arms.

And so, as she wrote, she became Zora Neale Hurston, born in Eatonville, Florida, in 1901, later reiterated in obituaries, and then, when Robert Hemenway published his biography in 1977, that story became the story.

“I think us here to wonder, myself. To wonder. To ask. And that in wondering bout the big things and asking bout the big things, you learn about the little ones, almost by accident. But you never know nothing more about the big things than you start out with. The more I wonder, the more I love.”

― Alice Walker, The Color Purple

In 1900, a census enumerator’s longhand told a decidedly different story. Twenty-four lines down the census form, her father’s name appeared, followed by her mother’s, their nine children, and the detail that Zora was born on January 7, 1891 — a decade prior — and 437 miles northwest of Eatonville in Notasulga, Alabama.

Roughly 10 miles north from Tuskegee, nestled in the Black Belt of Alabama, the town of Notasulga straddles the edge of Macon and Lee counties, 35 miles west of the Georgia border. Through the pines, serpentine creeks carve past former Indian settlements, plantations, and tenant houses.

Along an oxbow of Sougahatchee Creek, one finds Hurston’s paternal grandparents set back in a Baptist cemetery just outside Notasulga. In another cemetery just off Main Street, one finds Hurston’s maternal grandparents beneath the shade of a tree. For her parents, their marriage was akin to a Reconstruction-era Romeo and Juliet. A creek that ran through town divided the high cotton from the less prominent families, and in turn, that ribbon of water divided John from Lucy. The town, their unlikely marriage, and Hurston’s inheritance would form the nucleus of her first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine.

It’s not clear when Zora Neale Hurston’s family moved to Eatonville from Notasulga, but it’s evident she had few memories of the place. But by the time her brain did begin recording, she felt her father resented her.

“I don’t think he ever got over the trick he felt that I played on him by getting born a girl, and while he was off from home at that,” she wrote in 1941. She felt distant from her father but loved by her mother, and then in 1904, death bowed to Lucy.

“Death finished his prowling through the house on his padded feet and entered the room,” Hurston wrote. “He bowed to Mama in his way, and she made her manners and left us to act out our ceremonies over unimportant things.”

Further down, she continued, “That hour began my wanderings. Not so much in geography, but in time. Then not so much in time as in spirit.”

In the wake of her mother’s death, she left for Jacksonville. Her father remarried quickly. The distance between them grew and metastasized.

By 1916, Hurston headed north as a maid for the Gilbert and Sullivan theater troupe, eventually attending high school in Baltimore when she was 26. By 1918, she enrolled in Howard University’s preparatory school, and there, she started to draw up stories from a deep well. The same year, her father would be struck and killed by a train. She published her first short story and poem in 1921. Four years later, she moved to Harlem, enrolling at Barnard College. That same year, she’d meet Fannie Hurst, Carl Van Vechten, and Langston Hughes.

In 1927, she’d marry in St. Augustine, Florida, garner her first fellowship to collect folklore in the South, and meet Charlotte Osgood Mason, the patron known as “Godmother” who supported a number of artists during the Harlem Renaissance. That same year, she’d travel to Plateau, Alabama, and begin reporting her first book about Kossoula, who was then believed to be the last living freed slave to survive the Middle Passage.

In 1928, she’d divorce, receive her bachelor’s degree, publish How It Feels to be Colored Me, and the hurricane that later formed a central scene in Their Eyes Were Watching God would lash Florida — killing over 2,000 people along the shores of Lake Okeechobee.

Over the next decade, her writing became as fierce and sharp as that storm. Her manuscript detailing Kossoula’s life was rejected in 1931, but she signed a three-book deal in 1932 with J.B. Lippincott, and for the following 15 years, they took to each other like rain to soil. Her first novel hit shelves in 1934, after she spent six weeks in a cabin writing. Her first collection of folklore came in 1935, and in 1936, she earned a Guggenheim Fellowship and made her way to Jamaica and Haiti.

The first page of “Their Eyes Were Watching God” written by Hurston in Port Au Prince, Haiti, Courtesy the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscripts Library at Yale University

That year — in just seven weeks — she wrote Their Eyes Were Watching God in Port Au Prince. When it reached readers, Lucy Tompkins of The New York Times wrote, “Indeed from first to last this is a well-nigh perfect story — a little sententious at the start, but the rest is simple and beautiful and shining with humor. The images it carries are irresistible.”

Another Guggenheim came in 1937. A job with the Florida Writer’s Project carried her to Eatonville in 1938. Her fourth book was released that year. An honorary doctorate, her second marriage, and then her fifth book by November 1939. This continued at mind-bending speed, and through it, she cultivated the unparalleled vulnerability and peripatetic curiosity evident in her letters.

“I have served and been served. I have made some good enemies for which I am not a bit sorry,” she wrote. “I have loved unselfishly, and I have fondled hatred with the red-hot tongs of Hell.”

Hurston while working for the Florida Writer's Project in the late 1930s, a collection of Hurston's with the infamous photograph believed to be her but later determined to be someone else entirely, Hurston beats a hountar in 1937, Courtesy University of Florida

In her work, there was a deep-seated, haunting concern with trying to reveal what made people human — their flaws, their bent, their bright and dark, their morbidity and ebullience. It seemed like she meant to chart out what made her human, too, and by proxy, something like the cartography of the human soul formed in her work.

In fast forward from 1940, she remained in the South, writing fervently and feverishly, married once again, published 3 more books, had 3 unceremoniously killed, worked as a librarian, maid, and as a substitute teacher. For the last 15 years of her life, she toiled on a biography of Herod the Great, with Maxwell Perkins as her editor until death took him in 1947. In 1955, Scribner’s rejected her manuscript.

Still, she continued. As writers do, she put her ass in the chair each day and stretched words across the page. By 1957, she moved to Fort Pierce to write a column for the Chronicle, pulling up stories from the same well she’d tapped four decades prior, writing on hoodoo, race, and migrant workers. But in the years to come, time would find her.

“The wind came back with triple fury, and put out the lights for the last time. They sat in company with the others in other shanties, their eyes straining against crude walls and their souls asking if He meant to measure their puny might against His. They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.”

-Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God, 1937

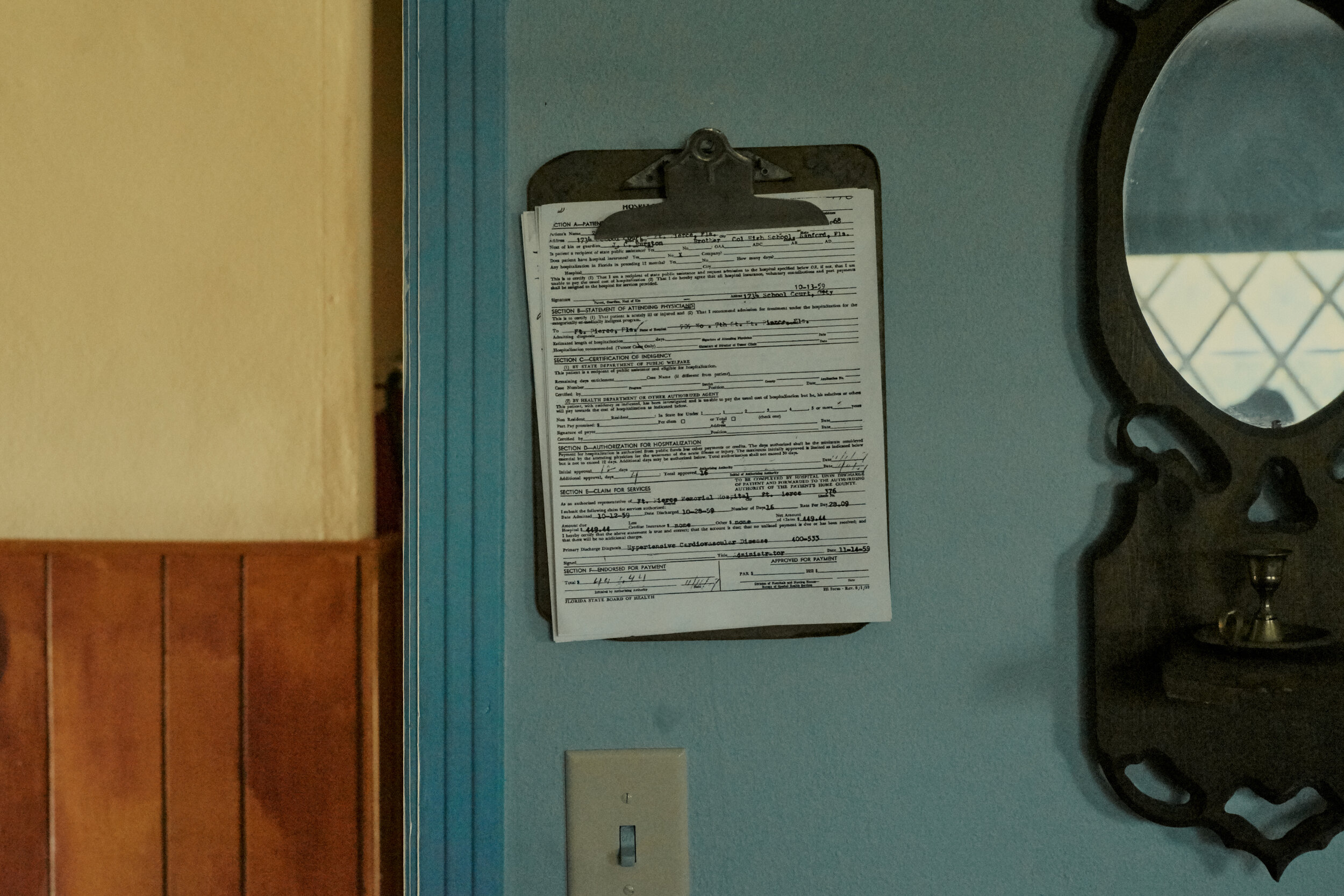

On August 21, 1959, a final demand for payment of $83.25 for treatment arrived from the Fort Pierce Memorial Hospital. “You will wish to act today,” it read. “Tomorrow may be too late.”

On October 12, 1959, she found herself laid up in that very hospital after a stroke. Sixteen days later, they moved her to the Lincoln Park Nursing Home, a segregated facility operated by the St. Lucie Welfare Agency. The place was just out the backdoor of the hospital, down a knoll through a field studded with slash pine and sabal palms. The man who owned her home, who allowed her to live there rent-free, also happened to be her doctor, Dr. Clem Benton. Later, he told Alice Walker, “She couldn’t really write much near the end. She had the stroke and it left her weak; her mind was affected. She couldn’t think about anything for long.”

In January, she wrote one of her last letters to Harper Brothers Publishing. In it, she implored them:

LETTER TO HARPER’S: Courtesy of the University of Florida Click to enlarge

Dear Sirs,

This is to query you if you would have any interest in the book I am laboring upon at present — a life of Herod the Great. One reason I approach you is because you will realize that any publisher who offers a life of Herod as it really was, and naturally different from the groundless legends which have been built up around his name has to have courage.

Sincerely Yours,

Zora Neale Hurston

After her first stroke, Zora remained Zora, despite her inability to write. She continued living at the nursing home where it was clear that everyone learned from her. Nothing could quell her tenacity. Hurston remained there through the new year, then she suffered another stroke on January 28.

That night, Death bowed to Hurston in its own way.

The staff rushed her across the street and up the hill, but by the time her body cleared the back door, she’d drawn her last breath. They pronounced her dead at 7:00 p.m., just as the light turned blue.

A few months later in a tribute, Fannie Hurst wrote, “She lived carelessly, at least at the time I knew her, and her zest for life was cruelly at odds with her lonely death.

“But death at best, is a lonely act.”

“Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonished me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It’s beyond me.”

—Zora Neale Hurston, How It Feels to be Colored Me, 1928

In 1994, at the fifth Zora! Festival in Eatonville, Robert Hemenway was there. On stage, he criticized his own biography of Hurston, running through a litany of things he felt he missed, because he was a white American writing about a black American — a man writing about a woman.

“It’s time for a new biography to be written,” he said, “and it needs to be written by a black woman.”

In the audience, Valerie Boyd felt a sting. “When I heard those words, I felt an inner calling,” she said. “I felt like: That’s me.” But as a young writer who’d never pushed past 5,000 words, a book seemed untenable. She sat there silently, but in her head, she told herself, “Maybe someday.”

Fifteen years earlier at Northwestern University, in 1981, Boyd first read Their Eyes Were Watching God. The idea that a book written 45 years prior could speak so urgently to her in that moment floored her. In Janie, the book’s protagonist, she recognized herself. In the language, she heard her grandparents. In Hurston’s books, she’d come under a spell.

By 1989, coffee mugs with Hurston’s face sat in her cabinets. Shirts hung in her closet. A sizeable portion of her bookshelf was lined with Hurston’s work, and so when she found herself in Eatonville for the inaugural Zora! Festival in 1989, there was this palpable sense of magic—to-be in that space, she said. “Only the true Zora heads were there.”

As though they were waiting for a green flash, she and her friends trained their eyes on a car that’d pulled up outside. And when the door swung open, out stepped Alice Walker, the keynote speaker that year. Trembling, Boyd remembered feeling starstruck, because as she said, “Even then, at 25, we knew how important she was to Hurston’s legacy.”

Then in 1996, Hurston chose Boyd.

Left, a photo previously believed to be Hurston but later debunked with a photo of her driving, Courtesy of the University of Florida

It came via phone, a literary agent on one end. They explained they were interested in a biography about Hurston and asked if Boyd might like to write it. Of course, she would, and so she began mapping out how, because there was no choice.

First, she used Hemenway’s book as a roadmap, discerning what undeveloped real estate remained out there. She started with the folks he didn’t talk to, the periods unfilled, and graciously, he helped her find some of those early lines of inquiry. What had previously felt like a daunting challenge molted into something like a calling for Boyd. As a black Southerner, a writer, and as a Zora head, she felt possessed.

She started with the myths and what appeared to be facts. She made lists of who, what, and where, but rather than lean into research, Boyd had to get with anyone and everyone alive who knew Hurston, because time was running out. For a few years, she crisscrossed “Zora’s Florida.”

“I had to start walking in her footsteps,” she said, and it was on the road where she started to feel close to Hurston, drawing the same lines across the state Hurston had. At times, it felt like they were driving together — Hurston a silent companion guiding her turns on the highway.

“It sounds odd, but in a spiritual way, I felt like she would lead me to those answers.”

Once Boyd established that connection, she put down the first lines in earnest and disappeared into the woods.

At that point in 1999, she was on staff at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, working part-time so she could finish the book. The work was coming slowly, and the chatter of life roared at home, so she asked for book leave.

The paper said no, so she quit and cobbled together sums from friends to amass $15,000, and she pointed the car south on I-75 for Sarasota, Florida — a little town along the Gulf of Mexico due West from Fort Pierce.

Boyd hemmed herself into a condo on Lido Beach, because she knew a friend in neighboring Manatee County, enough to remain social but not enough to distract her, and so her days were spent putting one word after the other, writing like hell. But as the days ran out, she found herself tracing the edge of the Gulf as the sun sank, thinking about Hurston doing the very same.

Once tourist season came, Boyd headed north to Hilton Head in South Carolina, returning briefly to Atlanta, and then finally, she crossed the state line to Florida once more. She’d planned to finish the book just a stone’s throw from Eatonville in Winter Park, but when that plan took a turn for the worse, she called her former landlord in Sarasota to see if she could hole up there. The landlord said come on; she’d leave the key under the mat.

In September 2001, Boyd filed the manuscript for Wrapped in Rainbows. Boyd returned from the post office and basked in one last sunset along the Gulf. “Maybe someday” was no longer someday.

She found it funny that among her friends, she was considered the “stable” one, but now she was living on bite-sized chunks of money, living out of a suitcase, and itinerant. For Boyd, that was tantamount to forming a connection to Hurston.

“I felt like I needed to experience that myself to write about it authentically,” Boyd said. She recalled Hurston’s first book acceptance, because when Hurston returned home that afternoon with the letter in hand, she found her belongings strewn across the ground, a pink slip stuck to the door. She’d been evicted.

“I didn’t come quite that close,” Boyd said, laughing. “But having that experience of moving from place to place while trying to create brought me closer to Hurston.” Boyd came to love Hurston for innumerable reasons, especially after so much time on her trail, but Hurston’s ability to be herself no matter the company or place, unapologetically so, stuck with Boyd.

“She was always herself,” Boyd said.

“Why are we reading, if not in hope of beauty laid bare, life heightened and its deepest mystery probed? Can the writer isolate and vivify all in experience that most deeply engages our intellects and our hearts? Can the writer renew our hope for literary forms? Why are we reading if not in hope that the writer will magnify and dramatize our days, will illuminate and inspire us with wisdom, courage, and the possibility of meaningfulness, and will press upon our minds the deepest mysteries., so we may feel again their majesty and power?”

— Annie Dillard, The Writing Life, 1989

As soon as the light came up, Antoinette Scully and her friends tore off through town. During the summer, they rode their bikes all over town as long as they returned by dusk. In the 1990s, Eatonville still remained a small, tight-knit town.

“Everyone was your neighbor,” Scully said. There were no secrets.

Just off the main artery that cuts through town, Scully and three generations of her family grew up. In 1881, the one-room structure became the first church in town, serving three congregations. It preceded the town’s incorporation by six years, and at one point, Hurston’s father would preach in this very structure. Eventually, the congregations outgrew the building, and so they moved the original building across the street to build a bigger church. The structure they moved would become the first library in Eatonville, then a juke joint, and eventually it became Scully’s family home. They call it the Thomas House.

The Thomas House in Eatonville

Growing up in Eatonville, Hurston’s legacy was everywhere. There was a marker outside Scully’s bedroom window. It was a time of year in January when Eatonville hosted the annual Zora! Festival. There was pride that a woman from this very acre became an author as well-known and important as any.

“In general, people love the idea of her,” Scully said, “Because her essence, the idea of what she stands for, helped save the town.” Hurston was to Eatonville what Flannery O’Connor was to Milledgeville, Georgia, or William Faulkner to Oxford, Mississippi.

In 2015, Scully and her husband were raising two kids in Los Angeles, making periodic returns to Florida, and Scully remembered the wellspring of activism in the wake of Michael Brown being killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri.

“The culture around blackness was shifting to a much more public concept,” she said. Black Lives Matter catalyzed. The public conversation reached a fevered pitch, and Scully, who’d spent almost her entire life in an all-black town, felt adrift.

“I had never heard of most of the things people were talking about. I felt disconnected from that history,” she said, and the frequency with which black men and women were being killed by police shook her. “I felt unsafe — all the time.”

During that period, Scully parlayed her fear into pilgrimage. She decided to read only black authors for the next year. Of course, Hurston was an author she knew intimately, but this was her first time with Alice Walker, Audre Lorde, or bell hooks. There were entire worlds she came across in those pages — worlds she felt inextricably tied to.

A pair of peacocks make their way through the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Fort Pierce

By 2016, Scully decided to start writing about her experience online. She registered a URL, secured a host, and called it “Black & Bookish.”

She wondered, “Maybe somebody will care?”

Evidently, people did. By July, a slow drip of emails arrived. And month by month, requests to speak at events appeared, queries to read manuscripts, review books, and suddenly, Scully was deriving a portion of her livelihood from Black & Bookish. And along the way, something had her thinking about home, about the Thomas House.

“I have dreams of that house,” Scully said. It came to haunt her, and soon she took to the idea of opening a bookstore there.

She persuaded her husband and two kids to move back to Florida, and by January 2017, she split her time between town hall meetings and renovating the Thomas House. But by autumn that year, she felt adrift again. “I thought I could go back and be the same person I was in my 20s,” she said, “but you can’t.”

Scully’s story conjured Hurston, because when Hurston first returned South, she felt out of place, even in Eatonville, and so she returned to New York black and blue. “I went back to New York with my head between my knees and my knees in some lonesome valley,” she wrote. But in time Hurston would come to understand the leaving and returning as integral to her staying, and the sentiment made me think the same might hold true for Scully.

By the end of 2017, Scully and her family moved back West, but it was that sequence of coming and then going that gave her some clarity about her home. As Hurston once put it, “I couldn’t see it for wearing it. It was only when I was off in college, away from my native surroundings, that I could see myself like somebody else and stand off and look at my garment.”

Scully remembered when she first left Eatonville, “I was lost.” Eatonville was in many ways a bubble, an entirely black town pressed up against the edge of the metro Orlando area, but small, sealed off.

“It wasn’t until I had to go to first grade that I was even in a classroom with white people,” Scully said. It was the first time she’d known anyone outside Eatonville, and she recognized that in Hurston, too.

Scully understood Hurston’s opposition to the Brown vs. Board of Education decision in 1954, which many found reprehensible then.

“I get that,” she said, because she, too, grew up in a segregated town, the very same as Hurston, but it was a different sort. “We built the town, so we’re exactly where we wanted to be. We’re not the black part of a white town. We are our own black town.” Black families have owned property there for decades. Roots run deep; heritage is hewn like wood into a sense of place that’s almost innate for residents.

“It’s like growing up in Mecca,” Scully said. “It’s almost like how white people grow up. That’s how I feel sometimes.”

A Peacock passes along storefronts on 17th Street in Fort Pierce

This past January, the Zora! Festival celebrated its 30th anniversary. Zora Neale Hurston would have been 128 years old. Some residents in Eatonville bemoan the direction town leaders are headed — pointing at the worn, unoccupied storefronts along Kennedy Boulevard as testaments to their point. In some cases, folks feel that the tether to the town’s past is growing weaker as the years pass. Notions of growth have entered the conversation as well as the question of how a place retains its character. But for Scully, who is still quietly chipping away at bringing a bookstore to Eatonville, she feels as haunted by the Thomas House as she does Hurston.

Like Hurston’s legacy helped promote the legacy of Eatonville, Scully hopes the Black & Bookish bookstore will become one more link in the metaphorical chain of preserving Eatonville’s history.

“I have this desire to save Eatonville whether it wants to be or not,” she said. “It’s not a bustling town. But there is so much life.”

“You know we owe her. She wrote about black people the way we are. How we love. How we laugh. How we sing our songs and talk our talk. And I’m glad to see y’all are taking notice of her.”

— Viola Simmons on NPR’s “Morning Edition” in 1983

Night stretched out over the cemetery when Marvin Hobson arrived. With a flashlight, he wended his way toward Hurston’s grave. When he found it, a shock ran through him.

Hobson came to know Hurston’s work through teaching Their Eyes Were Watching God. But when he moved to Fort Pierce in 2005, he had no idea Hurston lived here, let alone died here. Once he did find her there in the ground, Hobson started to learn more about the town he was living in as much as he was learning about his own past.

Marvin Hobson, President of the Zora Neale Hurston Florida Education Foundation

“I’m a Yankee,” Hobson explained, but each summer, his family would drive south from Long Island to Virginia and North Carolina to visit relatives. There was something about the bucolic lifestyle, the wealth of nicknames and story that stuck with him, but it wasn’t until reading Hurston that he understood the Great Migration that carried his family from the South.

“I really saw how that movement affected my life,” he said. “Hurston’s work helped me to see my family, helped me to learn about my heritage that no one taught me.” It made him look back with a renewed fondness on those summer trips but also more closely in the place where he was starting to carve out his own life.

For more than 70 years, a block building along Ninth Street in Fort Pierce served as the last resort for many residents in the county, specifically for black residents turned away by the segregated hospital just a stone’s throw away. When Hurston first arrived there in 1957, it was the St. Lucie Welfare Home. Later, the building continued operating as a nursing home and finally as a recreation center, managed by a local church that rented it for $1 a month. When its director, Brenda Cooper, died in 2017, the county made plans for a veterans’ facility, but in one room, believed to be the room where Hurston stayed, Cooper had built an exhibit celebrating the writer.

“That’s where it started,” Hobson said.

The home where Hurston lived in Fort Pierce between 1957 and 1960

By 2018, Hobson took the reins of the Zora Neale Hurston Florida Education Foundation as president, and their first goal was to make this building part of Hurston’s story. When approached with the idea, county commissioners said there was nothing they could do to halt the veterans facility. “It was a done deal,” Hobson remembered, but the members of the Foundation scanned the county’s rolls themselves for a more suitable property, found plenty, and made the pitch.

That was when Marjorie Hurell, a former student of Hurston’s, formed a bond with the county administrator, Howard Tipton. And with a quiet tenacity, Hurell conjured in Tipton an empathy to the building’s past and to the notion of preserving Hurston’s legacy with it. Next came funding. Then an architect. A business plan. They gained followers and persistently navigated a road of red tape and meetings.

On July 16 this year, within the County Commission chambers, Hobson, Hurell, and a cadre of supporters sat clad in Zora gear, a palpable sense of promise in the air. When the agenda item appeared, Hobson’s fingers clutched the shirts they’d prepared to offer the commissioners as a thank you. A moment later, the commission voted to transfer the building to the Foundation. Inside Hobson, there was something like fireworks. A few days later, the deed appeared in his inbox.

That night, the members of the Foundation held an impromptu meeting in the building’s front room. A folding table with wood veneer sat in the center with a purple tablecloth draped across it. Around it, each chair served as a reminder of what a single voice could do.

Hobson led me through the building in August, past a life-size cutout of Hurston, down a hall with rooms flanking each side, pointing to where the offices would go, talking about a scheduled clean-up next week, and then he said, “Here it is.”

Details from the exhibit curated by Brenda Cooper to celebrate Hurston and her time in Fort Pierce

The exhibition that Brenda Cooper, the late director, curated to celebrate Hurston’s time here was still up. A desk, bed, and clothes from the 1950s were lined with Hurston’s books alongside framed photographs of her, and hanging beside the bed, her death certificate was fastened to a clipboard. Allegedly, this was the room where she died.

“Yeah,” Hobson said, as we both stood silent.

Back outside, the light was blue. With the next Zora! Fest on the horizon in Fort Pierce, Hobson leaned up against a post outside and explained how he hoped this space would become a portal to Zora’s Florida. He imagined something that could couple Hurston’s legacy with the history of Fort Pierce, something that could address not only how to preserve Hurston’s legacy but rather this community’s legacy.

At a meeting the following night, Hobson and the Foundation’s members filled the chairs before articulating a set of questions that would do just that.

Zora Neale Hurston’s death certificate hangs in the room she is believed to have died in

“Their voices rise … the pine trees are guitars

Strumming, pine-needles fall like sheets of rain …

Their voices rise … the chorus of the cane

Is caroling a vesper to the stars…”

— Jean Toomer, “Georgia Dusk,” 1923

The sun was making its way toward the Gulf by the time everyone arrived at the Hurston’s grave in February this year. Together, a dozen folks filed out of two cars. Among them was Valerie Boyd, Hurston’s second biographer. There was Deborah Plant, Hurston’s third biographer and the writer who edited Barracoon. And then — there was Alice Walker, the woman who resurrected Hurston.

Because 2019 marked the 30th Zora! Festival, the organizers invited Alice Walker as the keynote speaker to mark the occasion, but rather than take to the lectern herself, she asked Boyd if she’d interview her.

“Thirty years later,” Boyd said, “I’m sitting on stage with Alice Walker, interviewing her about our Zora.” Surreal was one way to put it. To return to the grave with Walker was something else.

As they edged across the brick path that stretches toward Hurston’s grave, they weren’t alone. A young woman had come after the festival on her own pilgrimage, and now walking towards her was Alice Walker. Painted on her face, Boyd recognized something. It was the same feeling she had three decades prior when she first laid eyes on Walker herself. Together, everyone hemmed in the grave as the sky bled orange, its seams pulling down blue, a blanket of clouds slipping across the state like 59 years prior at Hurston’s funeral.

Everyone set down flowers and oranges, laid stones and said thanks. And then with a bottle of wine, Walker poured libation around the perimeter of the grave, making a revolution before passing it to Boyd who did the same.

“It was one of those little bottles of wine, and I swear it multiplied,” Boyd said, laughing.

And when I asked Plant about that night, she laughed, too.

“Oh, that,” she said, then paused for a long time. “It was holy.”

“To help us understand the significance of this woman named Zora Neale Hurston in terms of her being a literary foremother and this revolutionary social scientist who declared that African American folk culture was the greatest cultural wealth on the continent. For someone to fathom that,” she said, her voice catching, “who was black, who was Southern…”

Finally, once the words gathered in her mind, Plant said, “Alice Walker got that. It’s just something to get.” And then, almost whispering, she added, “That’s love.”

A set of concrete columns with bronze reliefs honoring Hurston flank the path that leads to her grave today in Fort Pierce

For Alice Walker, this was the first time she’d returned to the grave since 1973. She looked around at the place, dozens of graves spread across the plot, and she remembered how wild it was then.

“It’s actually a cemetery now,” she told me, “Not just backwoods. There are houses within view. There’s a gate. It’s become a real cemetery, and she has a place in it — surrounded by other people, so she’s not alone.”

To be there with so many people was joyful for Walker.

“We were thinking about how much it had changed for her,” she said. Now, people know Zora and her story, and they respect her work. It was encouraging to know that when people come to know something, Walker said, “they rise to the occasion of saving it, of understanding that they almost lost something so dear.” It was clear that these women standing around the grave were talking across time and place, between physical and metaphysical worlds. They were speaking across generations.

Forty-six years ago, when Walker left Florida to return home, she remembered thinking during the flight home, “If you want a job done, you do it yourself. Get on with it.”

She said she realized, “Don’t even bother to ask other people, because if they don’t feel it as you feel it, it’s just not the same journey.” Relief washed over her on that flight home. “I was happy. It was my responsibility. I really understood that.”

She thought on it for a while and said, “Whenever you fulfill what it is that you’re supposed to do, whatever that is, there is a sense of peace that may grow large as happened in the case of Zora’s work, or it may never be known.

“So many things are not known. But, that’s not the point,” she said. “The point is to get done what you can get done.”

“Perhaps love is a compelling necessity imposed on man by God that has something to do with suffering.”

— Zora Neale Hurston, Herod the Great

Just north of the cemetery in Fort Pierce, Taylor Creek carves across the state. Further west, it crosses through the lakes and wending ribbons of water that flow north toward Eatonville. Along a dogleg that bends south, it meets Lake Okeechobee and inevitably runs down to the area Hurston immortalized in Their Eyes Were Watching God.

From the lake, that sweetwater runs west through the Caloosahatchee and into the Gulf of Mexico where 400 miles north lies the Mobile-Tensaw Delta — the place where Hurston put down Kossoula’s story for us. Further into the heart of Alabama, one finds Notasulga, where her own began. And finally, if you follow the creek east from the cemetery, it spills into the Indian River and carries into the Atlantic Ocean. And from that point, water leads to all the places important to her, to all the things she revealed to us between Harlem and Haiti.

Hurston gave shape to eternal things like time or lust, mourning or dusk. She helped us realize that if you look at something carefully enough, what appears prosaic can become profound. She helped us believe that even in the dark, one finds things drenched in light.

Like Walker wrote, “There is enough self-love in that one book — love of community, culture, traditions — to restore a world. Or create a new one.”

And as she told me, “Hurston did work so hard to leave us something we could recognize of truth, of sanity, of beauty — and grace. This is something she left for us.”

“While I am still below the allotted span of time, and notwithstanding, I feel that I have lived,” Hurston wrote in her 1941 autobiography.

“I have had the joy and pain of strong friendships. I have served and been served. I have made enemies of which I am not ashamed. I have been faithless, and then I have been faithful and steadfast until the blood ran down into my shoes. I have loved unselfishly with all the ardor of a strong heart, and I have hated with all the power of my soul. What waits for me in the future? I do not know. I can’t even imagine, and I am glad for that. But already, I have touched the four corners of the horizon, for from hard searching it seems to me that tears and laughter, love and hate make up the sum of life.”

By the time death bowed to Hurston 19 years later, she was somewhere between those four points — tears and laughter, love and hate. She was there and then gone, maybe nowhere at all, but on that night as the light fell west and a blue pall came over Fort Pierce, she was glowing, and all these years later, she still is.

Michael Adno is a writer and photographer from Florida. He contributes regularly to The Bitter Southerner, The New York Times, and The Surfer’s Journal. Earlier this year, he won a James Beard Award in Profile Writing for “The Short & Brilliant Life of Ernest Matthew Mickler,” which was published here.

A story such as this requires great assistance, and Michael has some thank yous: “In the spirit of this piece, I’d like to thank everyone who lent their time and their voice along the way. Thank you first to Alice Walker for ensuring that we know Zora Neale Hurston. Thank you to Robert Hemenway, to Valerie Boyd, and to Deborah Plant, for giving us a more fluid and layered understanding of Hurston, and thank you to all the scholars, thinkers, and folks who have done the same in innumerable ways. Thank you to Antoinette Scully and Marvin Hobson for their faith in this story, to Kevin Young for his generosity, and to Florence Turcotte for an unrelenting curiosity and openness that formed this story’s departure point. Thank you to the folks at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscripts Library at Yale University, the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University, and the George A. Smathers Special and Area Studies Collection at the University of Florida, which provided me with a grant to report this piece. Thank you so very much to Dr. Tru Leverette, who first showed me Zora Neale Hurston in Jacksonville, Florida. Finally, I thank Zora Neale Hurston for making our world a bit bigger and a hell of a lot brighter, too.