More than 100 years ago, Eugene Bullard escaped the Jim Crow South in a most unlikely fashion — as a stowaway on a ship to Europe. Bullard became a World War I hero, serving in the French Foreign Legion and fighting the Germans in the trenches. Then he became the first African American fighter pilot in history and fought the Germans in the air, earning the nickname "The Black Swallow of Death." When he finally returned to America, Bullard lived largely in obscurity. He set to work on his autobiography before he went to his grave in 1961, writing that his older brother, Hector, met a tragic fate. Today, their descendants still crave the truth about what happened to both of them.

Terrence Chester’s West Georgia neighborhood resembles an incomplete loop, an open circuit. Flanked by kids’ trampolines, one road leads in. Another leads out. But they don’t meet. Inexplicably, a house with a tall fence stands between them, blocking the way. I am there to make a connection. My profession, newspaper journalism, has failed Terrence’s family. I want to help him bridge the gap.

Terrence’s home outside of Carrollton is the one with yellow siding and blueberry-colored shutters. Standing on the front step, I’m nervous about meeting him in person for the first time. I have brought books, articles, and photos revealing details about his family. For months, I searched fruitlessly for surviving relatives of one of his ancestors. Until now. Terrence was skeptical when I reached out to him on Facebook. He searched my name online and found that, yes, I am a journalist, that I am who I said I was. He slowly let down his guard as we talked on the phone the first time. He agreed to meet me at his home. But his nervousness returned the day I saw him. He worried about what I would reveal to him, whether it would contradict what he knew, whether it would surprise him, hurt him. He distracted himself by flipping on a football game. Having his wife, Lacey, at his side helped. She is strong. Talking to her eased his mind. She helped him forget I was coming.

Terrence — he goes by the nicknames “T” and “Huggy” — greets me at the door with a handshake and a smile. I detect a glint of sadness in his eyes. Thirty-six, bearded and stocky, he wears a Tupac Shakur t-shirt. His long hair is pulled back into a pair of braids. It’s a Saturday, Terrence’s day off from cleaning cooling towers atop commercial buildings and installing water softeners. Lacey wraps herself in a blanket on the couch. Their two young daughters, Izabella and Tatyana, watch videos in their room, still coated in the green and purple powder they tossed for fun at a Girl Scouts charity event that morning. Their room is just down the hall from the bathroom, where they have spelled the word “Believe” in capital letters on the mirror.

Terrence Chester and his daughters, Tatyana (left) and Izabella (right)

I found Terrence as I dug through an archive at Columbus State University. Combing through old clippings, I spotted him in a 1997 Columbus Times Newspaper article that identifies him as a distant relative of Eugene Bullard. Terrence won a history contest in middle school with a presentation about Bullard.

He told the competition judges a remarkable story: Bullard, the son of a former slave, fled the Jim Crow South in the early 20th century, joined a band of gypsies in Georgia, and stowed away on a ship for Europe. He told the judges that when Bullard arrived there, he boxed professionally, he played the drums in a jazz band, he rubbed elbows with people like Louis Armstrong, Josephine Baker and Langston Hughes, he fought for the French Foreign Legion in World War I and was severely wounded. He told them Bullard would eventually become the world’s first African American fighter pilot and fight the Germans in the air. He spied for the French Resistance during World War II. A refugee, he narrowly escaped to the United States when the Germans stormed into France.

“A young black kid from the South doing tremendous things,” Terrence tells me. “Growing up like I how I grew up, you don’t really see a lot of that, you know? There aren’t a lot of stories that you are able to put your hands on to say, ‘Hey, you can accomplish whatever you really choose.’ You hear it. But as a kid you kind of grow up like, ‘Yeah, it is just something people say.’”

Our heroes inspire us to reach for more. Bullard did that for Terrence. Terrence went on to win the school history contest with his presentation. Then he won at the state level at Georgia Southwestern State University in Americus. Then he took honorable mention at the University of Maryland. While he was up there, Terrence and his family visited the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, where they gazed at a bronze sculpture of Bullard. The trip was a thrill. He had never been outside of Georgia before. And he had Bullard to thank for it.

Alice Bullard Chester, Terrence’s maternal grandmother, raised him in Stewart County, the same part of southwest Georgia where Eugene Bullard’s father was born into slavery on a plantation. Alice remembers her uncle, James Bullard, spending a lot of time with Eugene in what is Stewart County today. Now 86, Alice still resides in that county, where more than a third of the residents live in poverty, where every child in the school system receives free breakfasts and free lunches, and where the largest employer is a sprawling federal immigration detention center. Downtown Lumpkin, the county seat where Alice lives, is scarred by vacant and boarded-up buildings. Weedy lots, bare concrete foundations, and piles of junk line the route south from downtown to Alice’s Baptist church.

Terrence Chester’s neighborhood, just outside of Carrollton, Georgia

Terrence got out of Lumpkin soon after he graduated from high school. He thought about enlisting in the U.S. Army but decided instead — with Alice’s encouragement — to head off to the University of West Georgia. He studied there for several years before dropping out to raise his family. He worked at a local Winn-Dixie grocery store, managed an auto-parts shop — where he seriously injured his back — and then found a better job at a water-treatment company, a position that has allowed him to take most weekends and holidays off so he can be with his family. The job pays the bills, though he dreams of more. Terrence wants to be on stage. He landed roles in several plays while growing up in Lumpkin, once starring as Hamlet in a summer program at Andrew College in Cuthbert. He got hooked being someone else, escaping. It was thrilling for him to draw emotions out of his audiences. A fan of Marvel superhero movies, Terrence wonders if he can break into Atlanta’s burgeoning film industry. Eugene Bullard’s story tells him anything is possible.

I ask Terrence if he has any photos of his hero, the man who set me on the path to meet him. Cradling his cellphone in his hand, he flips to his favorite black-and-white picture of Eugene Bullard. Wearing his French military uniform, Bullard has his arms crossed. His chin juts out. He wears a serious expression. I see pride and determination. Terrence sees strength and pain. To Terrence, Bullard is sending a message: No matter what, I am going to accomplish what I have set out to do.

Eugene Bullard fled the Jim Crow South in the early 20th century and stowed away on a ship for Europe, where he boxed professionally and fought for the French Foreign Legion in World War I. Bullard would eventually become the world’s first black military pilot. [From the Craig Lloyd/Eugene Bullard Collection at Columbus State University]

Terrence carries with him another family story, a darker, more complicated one. Like Bullard’s story, Terrence first heard it from his grandmother, Alice. As Eugene Bullard was on his way to fame and fortune abroad, his older brother Hector was lynched in Georgia, according to Alice. When he was a young boy, Terrence had no idea what the word “lynching” meant. When Alice explained it to him, Terrence asked why anyone would want to do that to Hector. To Alice, the answer was simple: because he was black.

Alice told Terrence about Eugene to make him proud of where he was raised. She told him Hector’s story to serve as a warning in a nation still afflicted by racism. When Alice grew up in the Jim Crow South, she was denied use of a bathroom at the local movie theater. White students severely beat her son, Charles, when his school system was integrated — when white supremacy was threatened. Alice’s uncle, Jerome, was killed in Columbus in the early 20th century. His body was found near the Chattahoochee River. She said her family never learned who killed him or why, though she says it is possible he was lynched.

“My dad would sit on the porch some days and say, ‘They killed Jerome for nothing,’” the retired domestic worker told me as we sat in her tidy kitchen in Lumpkin. “I think he was afraid to talk about this stuff.”

Terrence has his own stories. His home in Carrollton sits about 20 miles south of where a neo-Nazi group burned a swastika last year. A customer at the auto shop where Terrence worked in Bremen told him, “Every parts store needs a negro.” Another customer called him a nigger. Terrence is followed around when he shops in Georgia. He once brought up the fate of Michael Brown, the unarmed black teenager who was gunned down by a white police officer in suburban St. Louis five years ago. A white acquaintance in Carrollton told him, “You need to watch what you say and stay in your place.” Because of such experiences, Terrence agrees with Colin Kaepernick, the former NFL quarterback who drew national attention by kneeling during the national anthem to protest racial injustice in America. Terrence once styled his hair into big Afro like Kaepernick’s. Tears come to his eyes when Terrence talks about how some things have not changed since Hector and Eugene were alive.

“Even though those things happened so long ago, it still feels consistent with what you see today, even though it is not as open, I guess you could say. And in some cases, it is,” Terrence said.

Harriett Bullard White is a descendant of Eugene Bullard. Growing up, she heard stories from her family about Eugene’s old brother, Hector, getting lynched.

The South has changed dramatically since Eugene Bullard fled Georgia, but it is still coming to grips with its history. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice (informally known as the National Lynching Memorial) opened last year in Montgomery, Alabama. It features 800 six-foot steel columns representing the counties where lynchings occurred. The names of victims are engraved on those columns, but Hector Bullard’s name is not among them. An attorney for the Equal Justice Initiative, the nonprofit behind the memorial, told me her organization does not doubt the Bullard family’s account of Hector’s lynching, but she said it is among thousands of such cases it has not been able to verify with records, often because of the fear and intimidation that surrounded the killings from that era.

Hector’s story is a source of pain that radiates through generations of Terrence’s family. It is a pain that pulses deep inside, impossible to reach, impossible to remove, impossible to get away from. Maybe if he could learn more about Hector, Terrence could better understand his ancestry and see a clearer picture of the path ahead for him and his children.

I sit on the couch next to Terrence, knee to knee, and we begin to share what we have learned.

Taken at the Rankin House in downtown Columbus where the Bullard Historical Marker is kept in storage.

Eugene Bullard’s friends kept urging him to write a memoir after he returned from Europe to America, according to Craig Lloyd’s 2000 biography, Eugene Bullard: Black Expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris. Eugene began his story in 1959, but he needed help. A friend introduced him to Louise Fox Connell. A published author and activist who fought bigotry, Connell was fascinated with Eugene’s story and agreed to assist him. Working late into the night, Eugene would write on long sheets of paper and turn them over to Connell the next day for editing. Two years into the project, Eugene felt stomach pains. Doctors diagnosed him with an advanced stage of intestinal cancer. He died within two months of that diagnosis. P.J. Carisella and James Ryan’s 1972 biography, The Black Swallow of Death: The Incredible Story of Eugene Jacques Bullard, the World’s First Black Combat Aviator, describes his final moments. On his deathbed, Eugene pulled the oxygen tube out of his mouth and attempted to smile before whispering to Connell, “Don’t fret, honey. It’s easy.”

Eugene called his autobiography All Blood Runs Red, insisting that all races are equal. His typed manuscript bears handwritten corrections. Some words are crossed out. Others are underlined. Many pages are missing. I retrieved a copy from the Craig Lloyd/Eugene Bullard Collection at the Columbus State University archive. In it, Eugene describes growing up in Columbus in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the youngest of seven children. Three of his siblings died as infants. His mother, Josephine Thomas, a Creek Indian, died when Eugene was still a young boy. When he was a child, Eugene almost lost his father, too. Eugene writes about the night a mob nearly lynched his dad, William Octave Bullard. William worked on the docks in Columbus, unloading supplies from boats steaming along the Chattahoochee River. He was so big and tall — six feet, four inches — and he was part Creek Indian, so his boss nicknamed him “Big Chief Ox.” One day, a white warehouse supervisor, a bully who had repeatedly tangled with William, attacked him with a large hook, striking him on the head and yelling, “I’ll kill you!” Bleeding, William lifted the man above his head and threw him into a cellar, knocking him out.

That night, William loaded his rifle and placed it under his bed. He told his children to keep quiet. Soon, they were awakened by the sound of horses galloping toward their small shotgun style house. A band of “crackers,” Eugene wrote, banged on their front door. They shouted for William to come out, threatening to break down the door. William blew out the family’s oil lamp. Hardly breathing, no one in the family budged. Eventually, the hammering and hollering subsided, and the mob gave up and left. The ordeal traumatized Eugene. He couldn’t sleep, worrying his beloved father would be murdered and that he and his siblings would be orphaned.

Eugene’s father found a new job far from trouble. He started working on the railroad outside of Columbus, going away for long stretches. The family began to split up. Eugene’s older sister, Pauline, the one who stepped up to take care of the younger children after their mother died, married and moved to Alabama. Eugene ran away from home, aiming for France, where he believed he could be free of discrimination. His father had planted the seed with rosy stories about that country.

The Craig Lloyd/Eugene Bullard Collection at the Columbus State University archive.

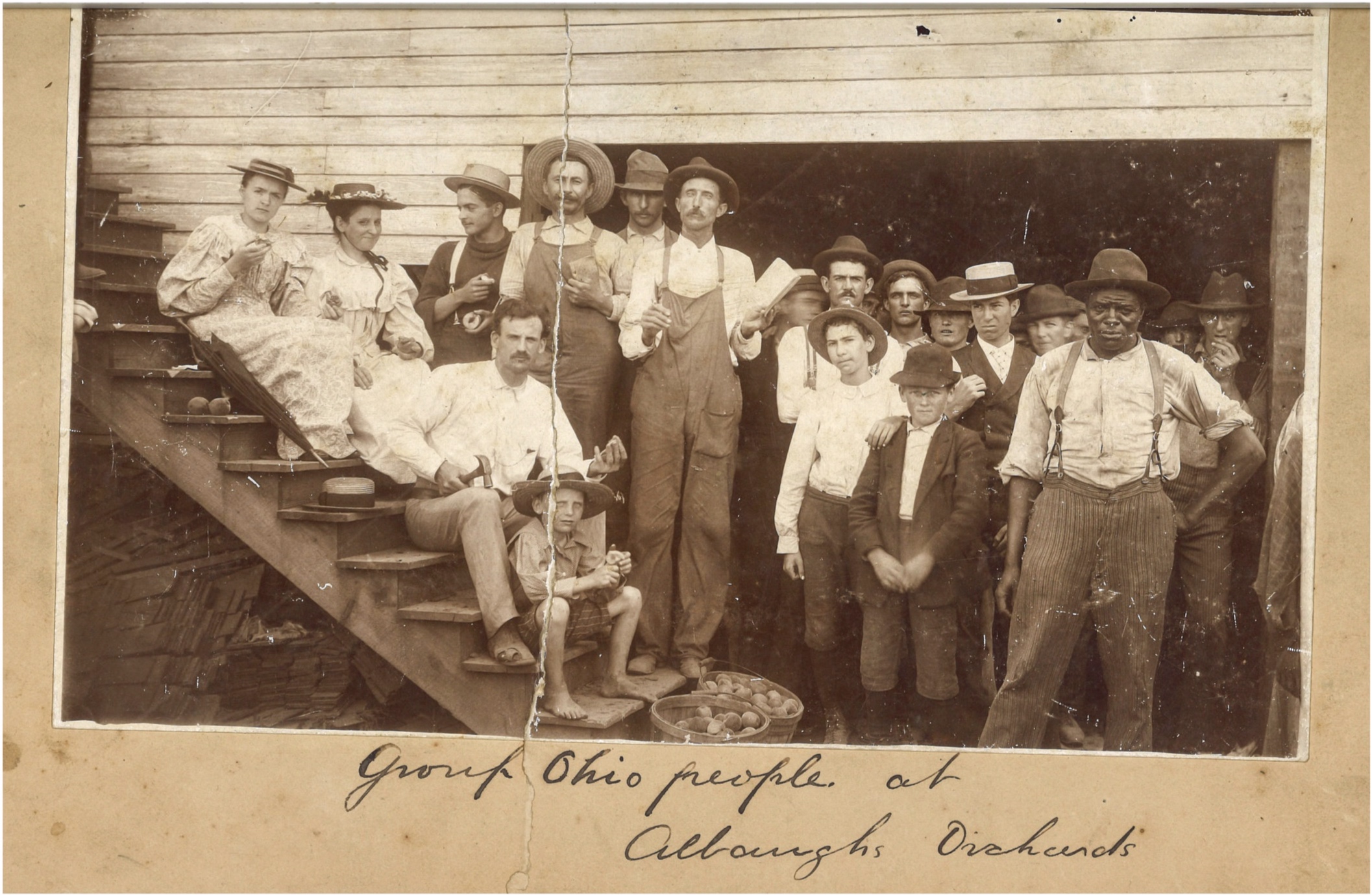

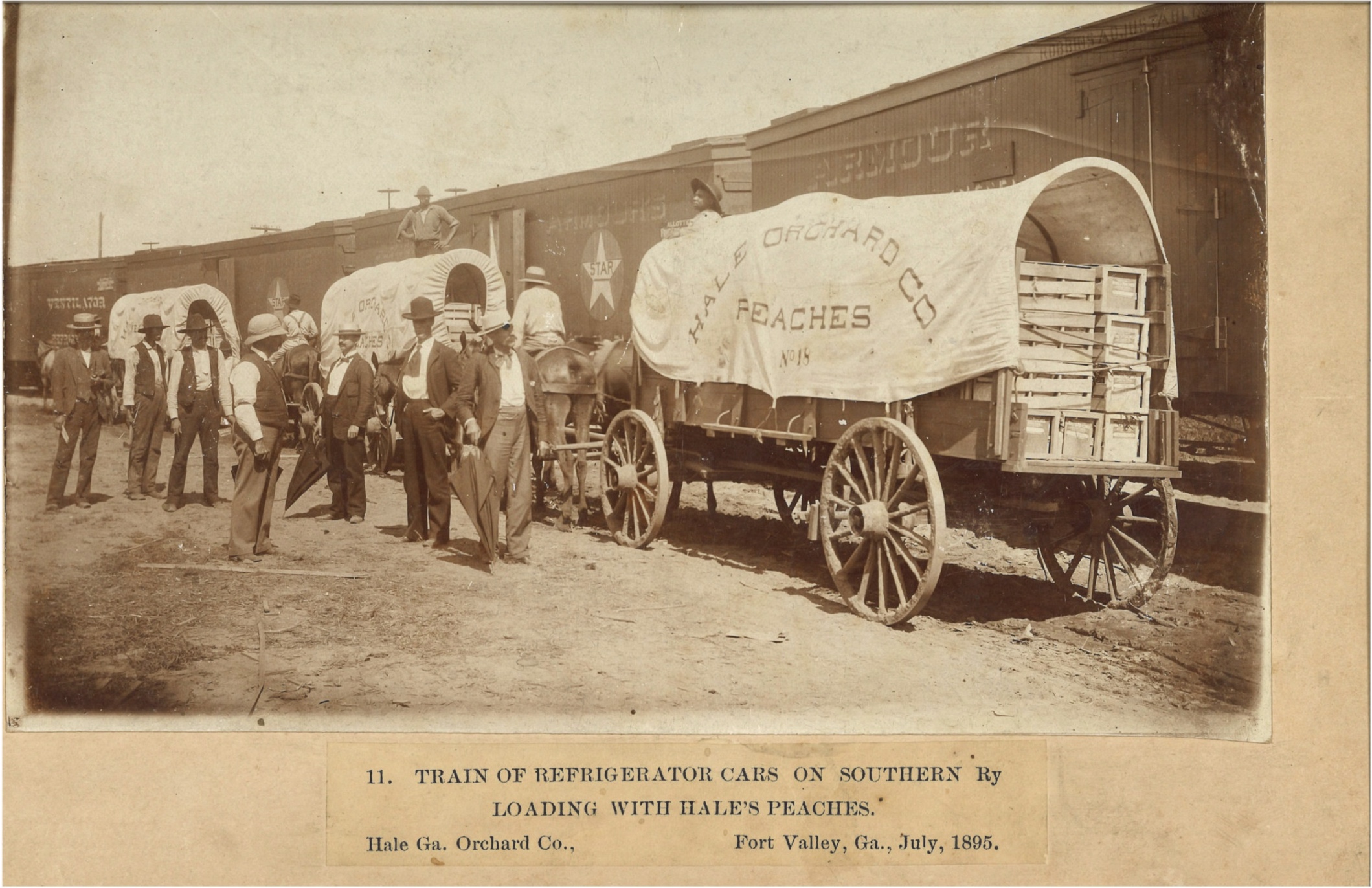

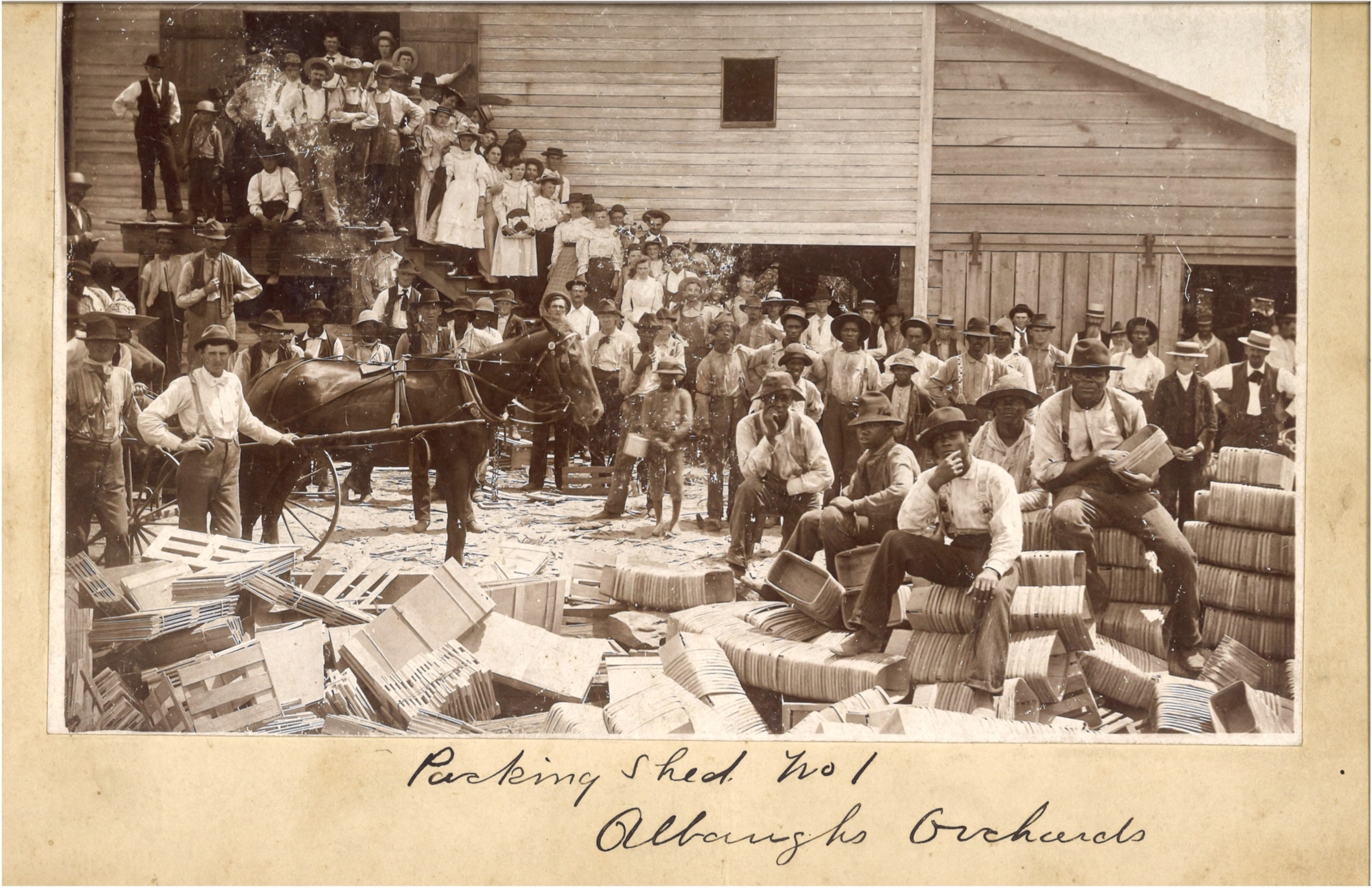

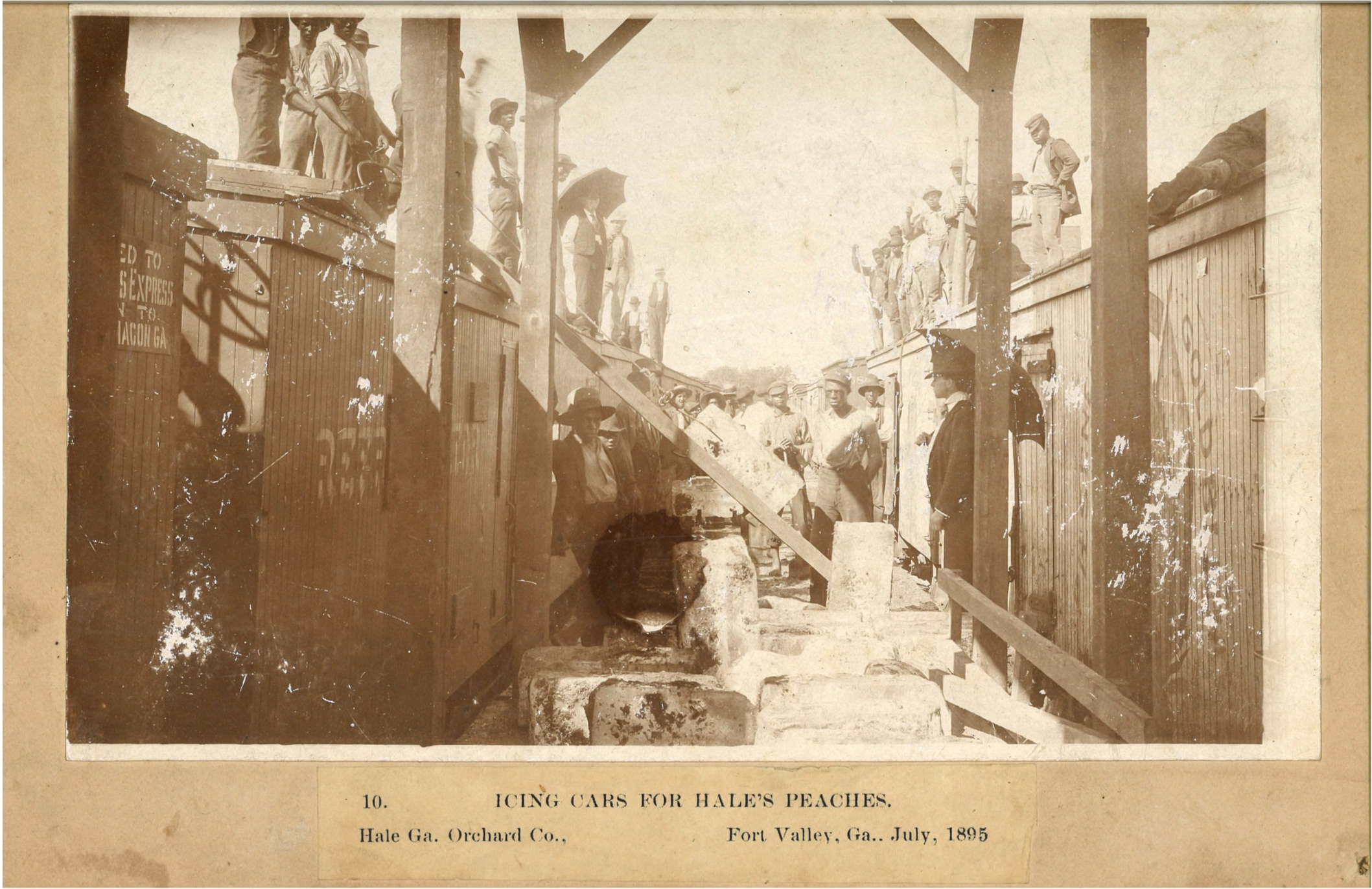

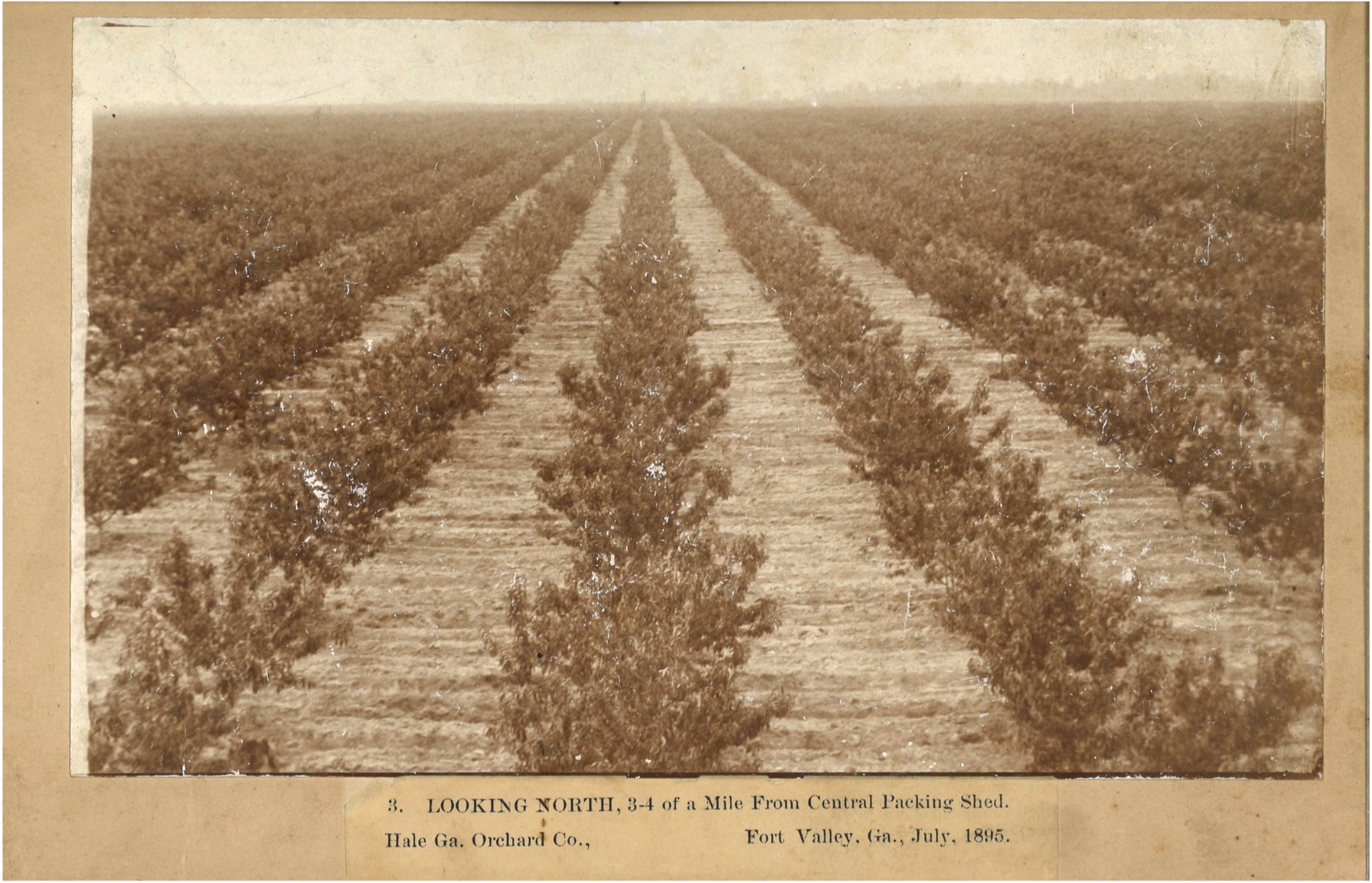

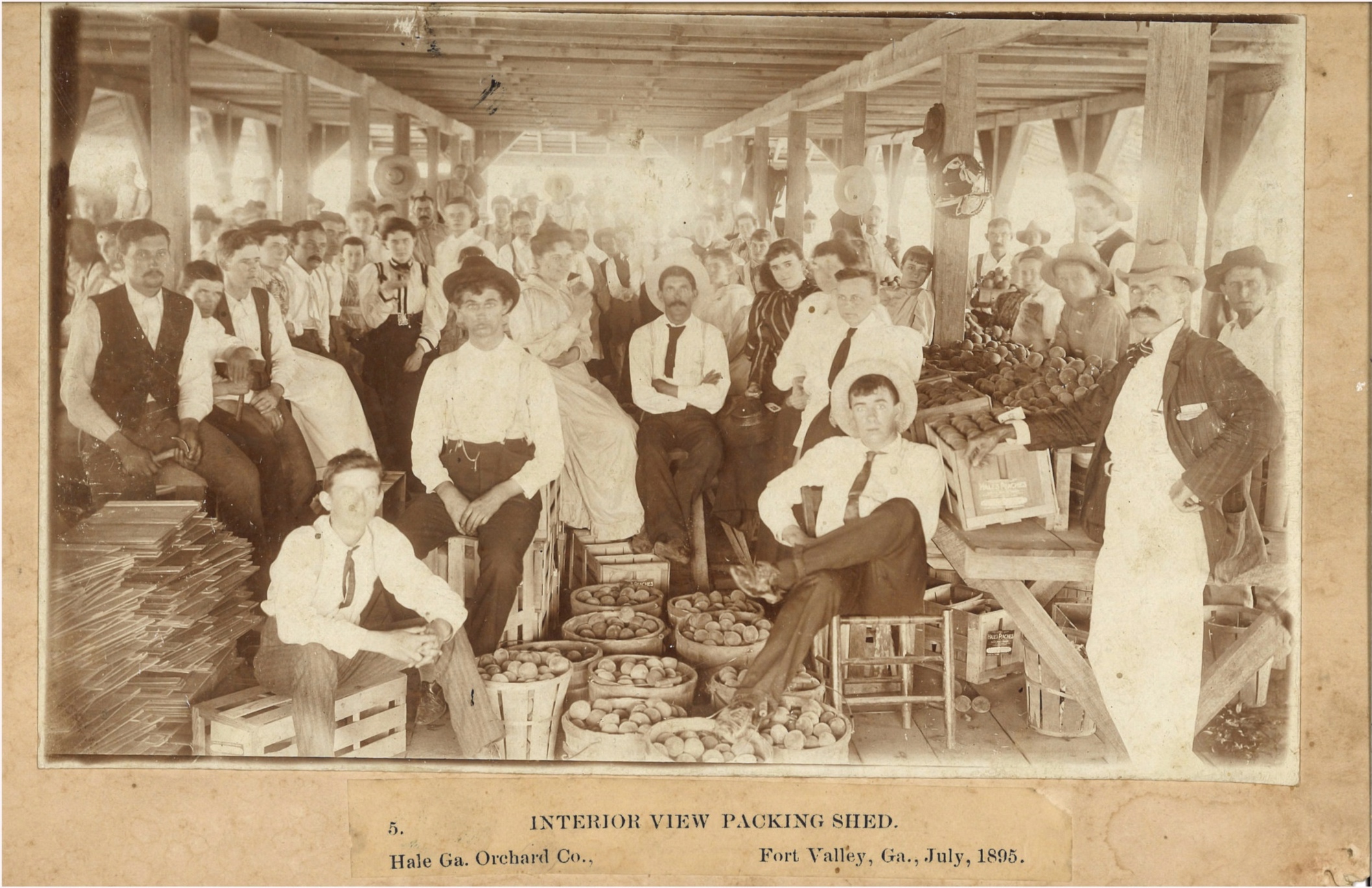

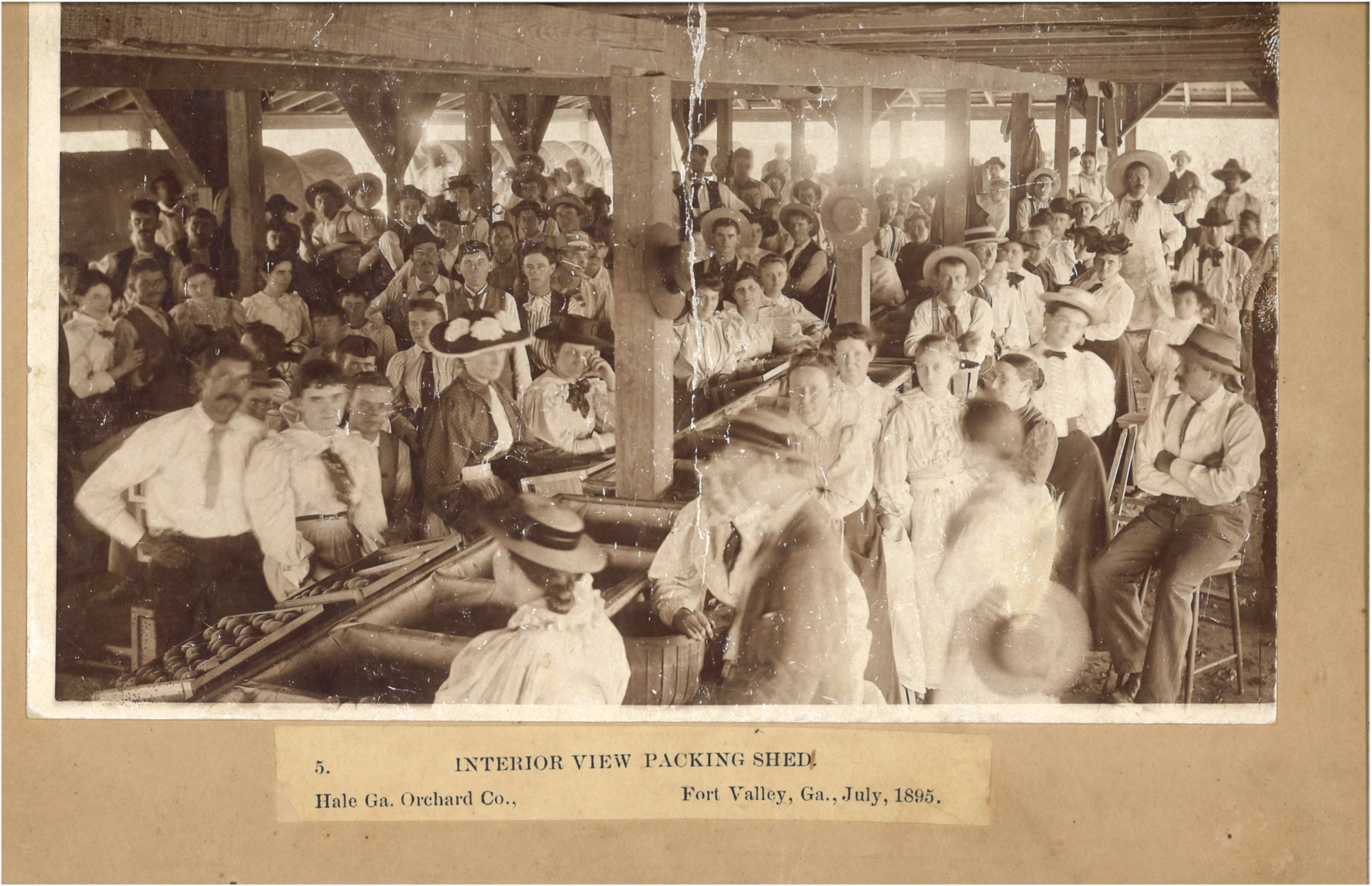

Eugene quit the South before the Great Migration, when millions of blacks fled North, bringing their dreams and much of the South’s potential with them. When he ran away, his older brother Hector was studying business administration at Morris Brown College, a historically black college in Atlanta. Hector was preparing to run a peach farm in Fort Valley, one of the biggest in the region. He inherited it from his mother, who inherited it from her mother. A white family — Eugene identifies them in his autobiography only by the first initial of their last name, “W” — had cultivated the farm for years, serving as overseers. The overseers would send Hector’s family money every year but without any accounting of how the farm was performing overall. Eugene writes: “The W. who ran it when Hector inherited it could not understand why he should not run the orchard to suit himself the way his father and grandfather had. But Hector was determined to manage his own property and was studying to do it right. Years later his attempt to win control of it got him lynched.” Short and direct, that last sentence lands like one of Eugene’s left jabs. With it, Eugene punches his older brother’s fate into history and leaves some clues about what happened to Hector. To Terrence, that passage reminds him of the painful stories his grandmother told him about white landowners taking advantage of his sharecropping ancestors.

Fort Valley’s peach orchards in the late 19th century.

I brought Eugene’s biographies with me. First, I ask Terrence to read a passage about Hector from Lloyd’s portrait of Eugene. Terrence begins: “White squatters on the peach farm near Fort Valley, Georgia, had hanged him when he insisted on pressing his claim.” Lloyd, who taught history and directed the archives at Columbus State University, told me he wasn’t able to independently confirm Hector’s murder. Next, I showed him Carisella and Ryan’s biography, which is based largely on Eugene’s autobiography. It says Hector was hanged on his own farm “by a mob of white night-riders” when he was in his mid-30s, though the biography does not cite any sources of this information.

“He got hanged on his own land? Wow,” Terrence says, sounding as if he has just touched a hot stove.

What we have read does not answer all of our questions about Hector. But I had uncovered a little more information to share with Terrence, some details that would bring Hector — and the South’s violent past — into sharper focus.

A peach orchard in Fort Valley today.

I tell Terrence I was confident when I set out to learn about Hector. I figured building a portrait of him would be easy. As a newspaper reporter for 25 years, I’ve written numerous profiles. To me, it was just a matter of gathering the information and putting it together.

I wanted to know what Hector was like, what happened to him, and why. My search of lynching databases and newspaper archives yielded nothing. I called Morris Brown College, where Eugene said Hector studied. There was no record of him attending college there. The library at Fort Valley State University, another historically black school, also had nothing to offer about him. Same story with the editor of the local newspaper in Fort Valley, the head librarian in town, and the current and former Fort Valley State history professors I tracked down. I spent the day in Fort Valley with Mayor Barbara Williams combing through a few cemeteries for Hector’s grave. We found nothing. I contacted Natalia Naman Temesgen, a creative writing professor at Columbus State University who wrote a play about Eugene Bullard, and she was just as stumped as me. I spoke to a distant relative, Harriett Bullard White of Marietta. Her great-grandfather was the brother of Hector and Eugene’s father. Growing up, she heard stories from her family about Hector getting lynched. But like me, she has no proof. I visited the Georgia Archives in Morrow and searched through voluminous deed and tax records but found nothing about Hector or his mother in the Fort Valley area, though I did find a Columbus city directory that confirmed he was there in 1906. It identifies Hector as a porter living with his brother Ben, a laborer. But I had nothing else to go on, not even a photo of Hector.

I knew I needed help, so I turned to an expert. E.M. Beck is a sociology professor emeritus at the University of Georgia who has spent decades documenting lynchings. He eagerly started digging as soon as I contacted him. He found census records showing Hector was born in September of 1887 in Georgia, probably in Columbus. He also found documents showing Hector married Sallie Umphrey in Muscogee County in 1906, when he would have been about 19. Beck and I could not find either of them in census records after 1900. Nor could we find a World War I draft card for Hector. And he does not appear in Georgia death records.

E.M. Beck is a sociology professor emeritus at the University of Georgia who has spent decades documenting lynchings.

I felt my stomach drop. After months of searching for Hector, I failed to learn much about him. Maybe I searched in the wrong databases. Perhaps I did not ask the right questions. Maybe I talked to the wrong people. Or maybe I had failed because of who I am, a white man living in the South, someone who has never experienced anything close to the racism Hector and Eugene endured, someone on the outside looking in. Or maybe that was all I was going to find about Hector. Perhaps it would be futile to dig anymore.

But I was obsessed with this thought: How could the brother of such a famous man vanish? Whether he was lynched or not, I concluded, Hector was another black man lost to history, lost in an era when many people did not consider the stories of black people worth retelling. In some ways, it was as if he were never born.

Beck sympathized with me when I failed to confirm whether Hector was lynched, calling his fate mysterious.

“It doesn’t mean it didn’t happen,” Beck told me. “It’s just that, given the complete lack of any information involved, it is an open case.”

Beck told me something else that sent me in a new direction. Three other black men were lynched in the same Fort Valley area where Hector was reportedly killed. They were among thousands of people who were lynched in the South in the 19th and 20th centuries. Perhaps if I could learn about these three men, I could shed more light on what happened to Hector.

The first man I read about was John Brown. In 1875, he was accused of attempting to rape a young white woman. The authorities arrested him and set off with him to a jail in Perry. But a mile outside of Fort Valley, a mob surrounded the marshal and a deputy sheriff, led Brown away, and hanged him from a tree. Four years later, Henry Walker was lynched for allegedly burglarizing someone’s home. A mob broke into the guardhouse in Fort Valley with a crowbar, dragged him out and hanged him from a tree just 15 feet away — in full view of a hotel and the railroad. And in 1903, Sandy Williams — he was nicknamed Banjo Peavy — was accused of gunning down a prominent white businessman, W. Cope Winslow, during an argument over a small debt Peavy allegedly owed him. The farmer fired twice at Peavy but missed. Peavy returned fire, shooting the farmer between the eyes and killing him instantly. Men chased Peavy for 15 miles through fields and swamps. He was hanged from a tree nearby and riddled with bullets. His killers reportedly fired 300 rounds at him. Peavy, Walker and Brown never faced a judge or a jury, just mobs carrying out their brutal executions.

I learned all of this from newspaper articles, which confirmed for me that Eugene’s account of his brother’s lynching is plausible. But those reports also revealed something else to me: the unreliability of our historical records. The newspaper accounts do not say precisely who accused Brown and Peavy of their crimes — they say Walker confessed to burglary — or identify who killed them. The bias and gleeful tone in some of the articles stunned me. The Americus Weekly Times-Recorder blared this about Banjo Peavy’s lynching: “Enraged Citizens Captured Black Fiend and Promptly Strung Him Up.” The article also refers to Peavy as a “black brute,” a “cowering wretch,” and a “murderer,” though he was never convicted of the crime. The Search Light, based in Bainbridge, Georgia, made light of his grisly murder with a pun: “Banjo must have been strung up pretty high.” The Vienna Progress, a weekly newspaper with an ironic name that covered Dooly County, Georgia, endorsed his killing with this editorial: “A lynching now and then goes a long way toward keeping things quiet in a neighborhood.”

I’ve made my career writing for newspapers. They have helped me pay for college, explore the world, and put food on the table for my family. To me, newspaper journalists are supposed to be the good guys. They are supposed to be empathetic, educated, and impartial referees standing up for truth and justice. But this journalism repulsed me. How could I discover what happened to Hector with accounts like these? Maybe newspapers didn’t consider him worth covering. Or maybe, if he was lynched, they didn’t even consider it murder.

Eugene Bullard never escaped racism, though he traveled so far away from the Jim Crow South. He flew at least 20 missions for the French in World War I, but was rejected as a pilot by the segregated U.S. military after America entered the fight in 1917. Historians have speculated he was turned down because he was black.

After narrowly escaping the Nazi invasion of France and after arriving in New York, according to his biographers, Bullard received an invitation to attend a reunion of former French legionnaires at the Paris Hotel, a towering 97th Street Art Deco building complete with a swimming pool and gym. He planned to go. But before the event, someone anonymously sent him a letter urging him not to show up, writing, “Your extended sojourn abroad has perhaps made you forget that in the states whites and coloreds don’t mix at social functions.” And it read, “It would be to your advantage not to attend the dinner on Monday night or to join in any social activities of the Post in the future.”

Never one to back down, Bullard went anyway, though he left his daughters behind so they wouldn’t face any trouble. The dinner was uneventful.

Eugene Bullard flew at least 20 missions for the French in World War I, but was rejected as a pilot by the segregated U.S. military after America entered the fight in 1917. [From the Craig Lloyd/Eugene Bullard Collection at Columbus State University]

Bullard received more than a dozen awards for his military service, including France’s Croix de Guerre for his heroism at the Battle of Verdun. Yet, he was forced to support himself with a series of menial jobs after he returned to America: longshoreman loading ships at a U.S. Navy yard on Staten Island, security guard monitoring a U.S. Army base in Brooklyn, and French perfume salesman making rounds in the Hudson Valley. One day while he was selling his perfumes near Peekskill, his biographies say, Bullard refused to sit at the back of a bus as instructed. The bus driver insulted him. In his mid-50s and always quick-tempered, Bullard went toe to toe with the driver. The driver punched Bullard in the face several times, causing him to lose sight in his left eye. The indignities continued in 1949, according to his biographies, when white police officers beat him at a concert he attended in New York for Paul Robeson, an actor and political activist who demonstrated against racism in America. When Bullard exchanged comments with a bystander and then an officer who was at the scene, the policemen clubbed him and knocked him down.

Bullard moved into a dilapidated apartment building in Harlem and found work as an elevator operator in Rockefeller Center. When the producers of NBC’s “Today Show” realized their good fortune that he was working in their building, they invited him on the program in 1959. Black and white photographs from the segment show Dave Garroway interviewing him and discussing his medals. Humbly, Bullard wore his elevator-operator uniform to the show. That same year, he was named a knight of the Legion of Honor, France’s highest award. A New York newspaper account quoted Bullard as saying the day before the award ceremony: “You might say I touched all the bases. Not much more you can do in 65 years.”

Terrence Chester delivered a speech about Eugene Bullard at his church last year, saying Bullard’s story shows “we all have a history, more than what people want to teach you in books, more than what you are going to learn in school.”

When I talk to people today about Bullard, many are astonished by what he accomplished, especially given that he grew up in the Jim Crow South. Most admit they had no idea who he was. It surprises me he is not more well known, particularly since he is an American war hero.

Georgia’s World War I Centennial Commission is planning to erect a statue of Bullard in October at the Museum of Aviation at Robins Air Force Base, just 20 miles east of Fort Valley. Terrence and his family also won’t let people forget Bullard. His oldest daughter gave a presentation about him several years ago at their Baptist church in Villa Rica for Black History Month. Terrence did the same last year. He dressed up for the occasion in a sharp white sweater and colorful bowtie. In a video his wife shot of his speech with her cellphone, Terrence appears slightly stiff and nervous. He keeps mixing up significant dates. And the forgiving audience keeps encouraging him to continue. The small church was full that day. Many children were in attendance. A keyboardist can be heard performing in the background, accompanying Terrence’s speech.

Calling him his great uncle, Terrence tells the audience Eugene Bullard was the first black military pilot. The audience murmurs its support, as if Terrence were the pastor of the day: “Amen!” He tells the audience Eugene lost his mother at a young age. Emotion is catching in Terrence’s voice. Eugene witnessed the near-lynching of his father. He stowed away on a boat and fought in Europe in both world wars. He ran a nightclub and served as a spy. And after all of that, he returned to America, where he lived mostly in obscurity. And he did it with humility.

Terrence Chester wants his family to keep Eugene Bullard’s story alive. He feels the same way about Hector Bullard. Now that he knows more about him, Terrence plans to share his story publicly, too.

“With all the awards and everything like that, at the time you were still black,” Terrence says of Eugene’s homecoming. The audience understands, “Yes. Um-hum.” Terrence continues: “There were no accolades for him here. He ended up becoming an elevator operator in New York. With all that being said, he took everything he did with pride, whether it was scrubbing the floor or running the elevator. He did everything with honor.”

Terrence says Eugene’s story shows “we all have a history, more than what people want to teach you in books, more than what you are going to learn in school. So my suggestion to all of you: Talk to your grandparents. If you have got great-grandparents, talk to them because there is so much to us as a people than you would ever learn — than you would ever learn — when it comes to...”

Terrence trails off. Struggling to fight off his emotions, he slaps his thigh. He peers upward as if he is seeking support from above. The crowd encourages him: “Amen!” But Terrence is done. And the audience is applauding and cheering.

Terrence tells me he will continue sharing Eugene’s story for the rest of his life. It makes him proud. And it reminds him that he can accomplish anything, despite racism’s stubborn grip on America. He wants his family to keep Eugene’s story alive. He feels the same way about Hector. Now that he knows more about him, Terrence plans to share his story publicly, too. It is like a wound that needs air to heal, he tells me. By exposing it, he says, maybe he can protect others from suffering. Maybe he can prevent Hector from being lost to history. Maybe by sharing Hector’s story, he can help us understand who we were then and who we are now. Maybe by sharing Hector’s story, Terrence can help us come closer together, help us bridge the gap.

A reporter for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Jeremy Redmon has written extensively about war, the opioid abuse epidemic and immigration. His assignments have taken him to the U.S.-Mexico border, Central America and the Middle East. He lives in North Georgia and is graduating this year from the University of Georgia's Master of Fine Arts program in narrative nonfiction writing.