Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration commemorating the end of slavery in the United States. It’s also complicated ...Celia Walker grew up celebrating it in Fort Worth, Texas, and is glad that the world is taking notice.

By Celia Walker

Freedman's Cemetery, Dallas, Texas, with Vickie Washington Nance. Photo by Classi Nance Photography

“Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; It must be demanded by the oppressed.” — Martin Luther King, Jr

June 19, 2020

June 19, 1865, General order No. 3 “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free … ”

As a child growing up in Fort Worth, Texas, I have fond memories of celebrating this holiday called Juneteenth. My mom was a recreation center director and participated along with other city facilities in the execution of one the largest local African American festivals in town. I would later find out that the celebration extended well beyond my town of about 500,000, at the time, of which roughly 15% was African American. Funny, in my childhood mind, it seemed as if everyone in town was celebrating, but it later became quite apparent to me that it was indeed an “all-Black” thing.

I looked forward to Juneteenth even more than other local holidays, like 4th of July or Mayfest and the well-known Fat Stock show that actually occurred in the fall so we had a day off from school. But nothing, not even a day away from the classroom, compared to the jubilation of Juneteenth. It was particularly different from all the others. For me, everything appeared to be tailored toward my and my community’s unique interests. The guest speakers were more prolific. The music was louder. The barbecue was smokier and smoked just right. The watermelon was sweeter and juicier, and the red soda pop of choice was “Big Red” and it was, of course, the reddest. And the fashion, the fashion was the flyest. Oh, how I loved to watch the people go by, finger-snapping and strolling through the park in their bell-bottoms or hot pants. As I would sit on the curb with my freshly-cornrowed hair, I would bask in the vibrant colors blended with the smells and sounds of the best party ever. June 19th was a full day of celebrating being Black and I relished every minute of it.

If you’re somewhat confused and unfamiliar with this holiday that I speak of, unfortunately, you have lots of company. Like many other facts about our American history related to slavery, this story has been hidden beneath the underbelly along with other untold stories of how Black people were treated or, better said, mistreated in the “land of the free, home the brave.” So, for the record, Juneteenth is the oldest and largest known celebration commemorating the ending of slavery in the United States.

On June 19, 1865, the Union soldiers, led by Major General Gordon Granger, announced the news that the war had ended and that all enslaved people were officially by law free in Galveston, Texas. Hence the combination of June and 19th (Juneteenth). Now, if you know American history, to any degree, you know that Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation became official on Jan. 1, 1863. So, yes, Texas did not receive the news until two and a half years later, and even then, there was much resistance. According to many accounts, Texas was the farthest west of the Confederate states, and, as records note, many slave holders from neighboring Southern states such as Louisiana, Mississippi, and other areas east began migrating to Texas as early as 1862 to escape the Union Army’s reach. In fact, by the time General Granger dispatched Order No. 3, two critical things had happened: Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated in April and Texas’ slave population had more than doubled to 250,000. In other words, the Lone Star State had, in essence, become a sort of haven for slave owners to viciously hold on to their “property” and free labor system which, by law, was now illegal. But who was watching? Virtually no one.

I say illegal, yet the grim reality at the time was that in most cases in the South, particularly in Texas, the lawmakers were slave-holders themselves. So what do you think happened? Laws were rapidly created to extend their power and control.

An example of this immediate rebellion was the establishment of The Black Codes. These were laws passed by Southern States in 1865 and 1866 in the U.S. following the Civil War. These codes were put in place by white Southerners to restrict the freedoms of newly emancipated African Americans. They continued to systematically oppress and suppress formerly enslaved people through manipulation, debt, low wages, and accusations of manufactured crimes. Sound familiar?

It is necessary to revisit General Granger’s Order No. 3 in its entirety:

"The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, become that between employer and hired labor. The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere."

Pay close attention to the last two sentences … essentially stating to the slaves, you are “free,” but …

In an essay by Elizabeth Hayes Turner, an heir to the Juneteenth tradition, she wrote, “the way it was explained to me, the 19th of June wasn’t the exact day the Negro was freed, but that’s the day they told them they was free.”

We should also be mindful of Abraham Lincoln’s overall motives regarding slavery. See his response to an article written in 1862 by Horace Greeley, the editor of The New York Tribune, pressuring Lincoln to take a stance on abolishing slavery.

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union and is not either to save or destroy Slavery,” Lincoln wrote. “What I do about Slavery and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save this Union ...”

“Explain to me why we celebrate Juneteenth, again?” That was the question I asked my Mom in 1976, which was the bicentennial year, and, ironically, the same year Alex Haley’s novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family was released. However, the real emotions wouldn’t start to stir until, like millions of other Americans, I was captivated by Roots, the television mini-series. I had never heard the story of slavery told in such a brilliantly raw and accurate way, and, most important to me at the time and even today, is that it was written by a Black man from a Black man’s perspective. Haley had meticulously researched his genealogy well before Ancestry.com or 23 and Me. This was groundbreaking and, for me, profoundly liberating.

The year following Roots, I wasn’t so eager to participate in the Juneteenth turn up. The rebel in me would emerge, the feelings were more visceral. So you’re telling me that we found out two years after everyone else? Shouldn’t we be protesting? Shouldn’t we be demanding our reparations? Why are we partying?

Interestingly, I wasn’t alone in my newfound Black-pride-anti-Juneteenth plight. Many African Americans in the ’50s and ’60s shared a similar sentiment, directing their energy toward the Civil Rights movement, education, and equal rights. Black people in America were focusing on the future rather than remembering the past. Juneteenth celebrations began to decline. By the 1970s, Black power movements across the country allowed a resurgence of the popularity of the holiday, and by 1979, Texas state legislator Al Edwards introduced a bill to make Juneteenth a Texas state holiday. The first state-approved celebration took place in 1980. As a result of this accomplishment, Edwards is often referred to as “the father of Juneteenth.”

When I spoke with the renowned African American historian Dr. Harry Robinson Jr, President and CEO of the Dallas African American Museum, I asked him whether Juneteenth should be celebrated or protested. Robinson has hosted the Texas Black Invitational Rodeo for some 31 years in honor of Juneteenth. Robinson was vehemently clear, his facial expression morphing into a sharpened stare, “We as a people should never pass up the opportunity to celebrate freedom, any type of freedom, regardless of the circumstance. To be free from bondage, whether it’s slavery, a hospital, release from prison or otherwise, it is to be free.” He went on, “Do you really believe the slave population in Texas gave a damn about finding out two and half years later? I doubt it very seriously. I imagine that there was indeed a set of turbulent emotions, joy, confusion, and possibly fear, but their new reality of freedom was then, and now, cause for celebration. And just think, our people managed to succeed in spite of the obvious schemes and plots to extend the hold of dependence. People believe that slaves and former slaves were docile but there were uprisings long before Juneteenth in Texas. Black people were courageous and resilient and went on to build schools, churches, and communities as a result of their determination. Juneteenth should be a time for teaching our history, to unpack untold hidden stories, and share with our young, to honor the sacrifices and achievements of our pasts and to be inspired by the strength of our ancestors.”

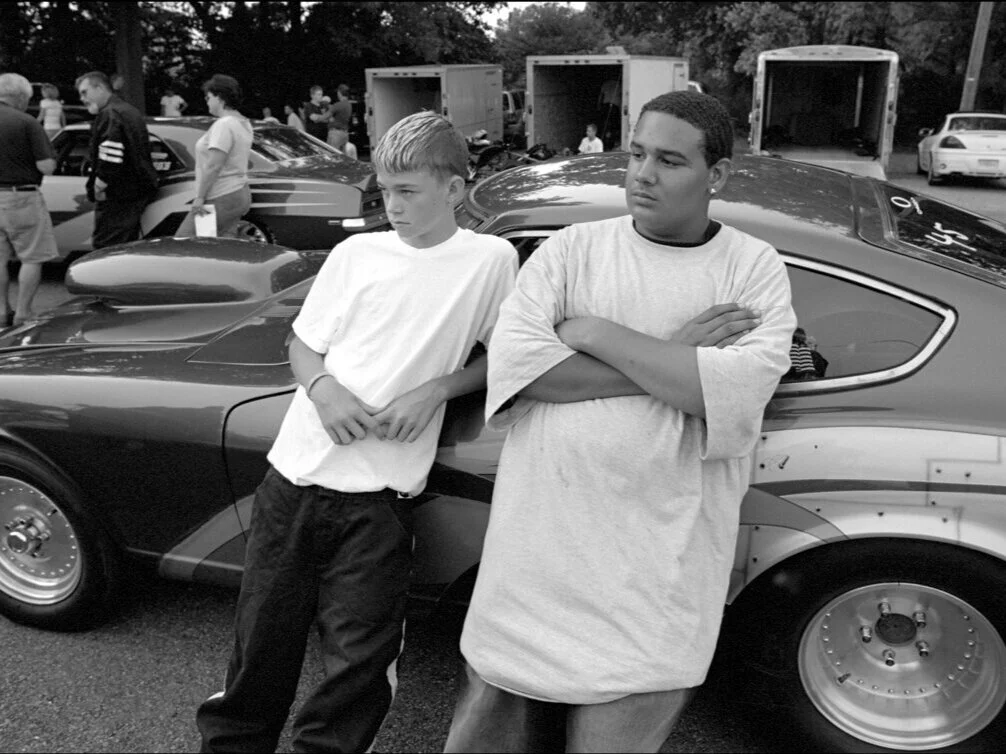

Photo by Classi Nance Photography

Robinson also told me about the Freedman’s Cemetery, an African American burial ground in the heart of Dallas established in 1861, that is considered one of the largest Freedman Cemeteries in the country.

I met with Vickie Washington-Nance, (Dallas born and bred, theater director, activist, and anti-racism facilitator), at the Freedman’s Cemetery to get her take on Juneteenth.

It was a hot Texas summer afternoon but neither of us was bothered by the heat, rather we walked the memorial grounds which were built in the early ’90s, with a sense of respect and admiration for what the statues and the very land we stood on represents. Freedom.

Washington-Nance’s earliest encounter with Juneteenth was fairly late, as a young teenager in the '60s. While she had heard of it, her family really didn’t celebrate it until her mother had opened a dashiki shop in south Dallas. On Juneteenth, she served red punch and would offer a buy one dashiki get one for a penny sale. She called it the “George Washington Carver special.” In her household, they were very clear about the larger history of us as African Americans so it felt like one more piece of information that proved, “We were more than we are told we are.” Her mother was the curriculum specialist for Opportunity Industrialization Center and part of her task was to order books that enriched young Washington-Nance’s education.

Washington-Nance shares a very specific memory of being a ninth grader at Boude Storey, a junior high school in Oak Cliff, Texas. The school was just turning over and there were still white teachers but no white students. Her world history teacher was a white man who she describes as a particularly unpleasant person who wore his pants real high over his belly. “You could feel that he didn’t want to be there,” she said. They studied Hannibal that year. She always loved school, reading, and learning. Over the summer, she learned that Hannibal was Black, north African in fact, and she was so upset that her white teacher had not revealed that to the class. She literally felt slighted. From this experience, Washington-Nance concluded that it is the responsibility of all African Americans to preserve our history and teach our children the history that they will never receive in the classroom.

Photo by Classi Nance Photography

“When people ask me why we celebrate Juneteenth, it’s akin to when people ask why they gave us February the shortest month — which, for the record, nobody gave us anything — Dr. Carter G. Woodson fought and instituted it, so both questions annoy me. It makes sense and it is only proper to celebrate and acknowledge that on this date our enslaved foreparents were given the news that they were free. That is honorable and necessary. There is all kinds of stuff that can be problematic around that. But if we [African Americans] don’t celebrate it who will?

“When I think about the word ‘free,’ I think about my mother who was born in 1929, and always would boast that she was born free, although she was a woman born free in a place and time that did not acknowledge and worked consistently to deny her that.”

“To come around to the notion of Juneteenth and the understanding of it, I think yes, we should celebrate it, honor it, commemorate it, know it! We should identify ways in which we will continually enact and live through our freedom. The freedom of knowing who we are, teaching our history, living our future. Those are not easy things living in a world and in a place which 24/7, 365 would try to deny that.”

I agree with both Robinson and Washington-Nance. Freedom should be celebrated in all its glory. Unapologetically, we should take on the spirit of our ancestors: giving glory to God and praising the possibilities of the beauty of freedom. As Pharrel Williams wrote in his song “Freedom:”

“Hold on to me

Don’t let me go

Who cares what they see?

Who cares what they know?

Your first name is Free

Last name is Dom

We choose to believe

In where we’re from …” Freedom!

"It is only after slavery and prison that the sweetest appreciation of freedom can come" — Malcolm X

This year, let’s remember Juneteenth for just that — simply put, we are Free!

Updated June 10, 2021.

Celia Walker is a native Texan but her heart is in Atlanta. She is a marketer by day and a writer by night! She loves tennis and all things stylish and believes that bacon makes everything better. Celia resides just north of Dallas with her husband and two children.

More from The Bitter Southerner