The rare Florida torreya tree grows only in the wild along a narrow stretch of the Apalachicola River. In the 1950s an eccentric lawyer named E.E. Callaway declared it was the gopher wood tree from which Noah’s Ark was built. Today the Florida torreya is on the brink of extinction. Can the story of this tree and the people who love it help bridge the gap between science and faith?

Story by Martha Park | Photographs by Johnathon Kelso

In the grainy 1972 televised interview, Elvy Edison Callaway’s back is curved over a polished wooden cane. He wears a white fedora, professorial eyeglasses, and the thinnest dusting of a white mustache. When he’s not talking, his mouth moves continually, lips smacking together as if eager for another chance to speak. Callaway had spent the last two decades trying to convince anyone who would listen that he’d made a monumental discovery. While combing through Genesis, he’d looked around northern Florida and noticed the ways the local topography — even the flora and fauna — seemed to match up perfectly with the descriptions of the Garden of Eden that he found in the text.

“The Bible gives us certain definite facts,” Callaway wrote in his 1966 book, In the Beginning, “corroborated by nature, science, and other unimpeachable evidence, which conclusively proves that the Garden of Eden was located east of the Apalachicola River, between Bristol and Chattahoochee, in Liberty and Gadsden counties, Florida.”

Just like the river described in Genesis, the Apalachicola flows east. Callaway observed four rivers that connect with the Apalachicola and concluded that the Flint River was once known as the Gihon; Spring Creek River was the Euphrates; the Chattahoochee River was once called Pishon; and Fish Pond Creek was once known as the Hiddekel, or Tigris.

The river could have been just a coincidence, but when Callaway read about the gopher wood that Noah used to build the ark, he thought it sounded a lot like the Florida torreya, what locals called the stinking cedar, a small subcanopy conifer that grows in the steephead ravines along the Apalachicola River — and nowhere else in the world. When Callaway unearthed three petrified gopher wood logs, each of them 20 inches in diameter and 6 feet long, he knew what he’d found: “They were cast off from the building of the Ark,” he wrote.

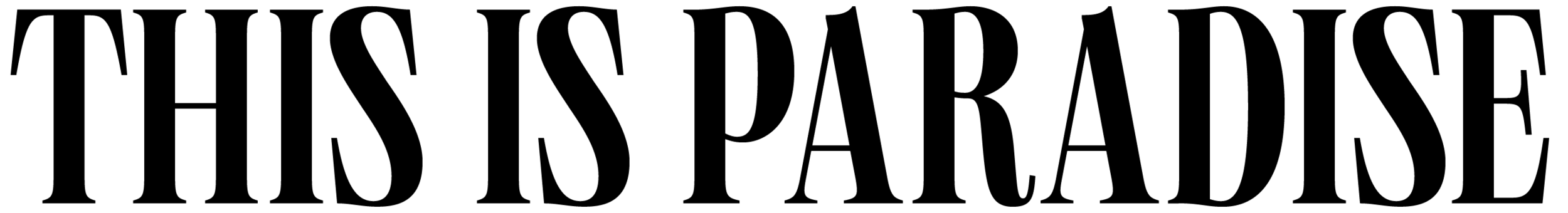

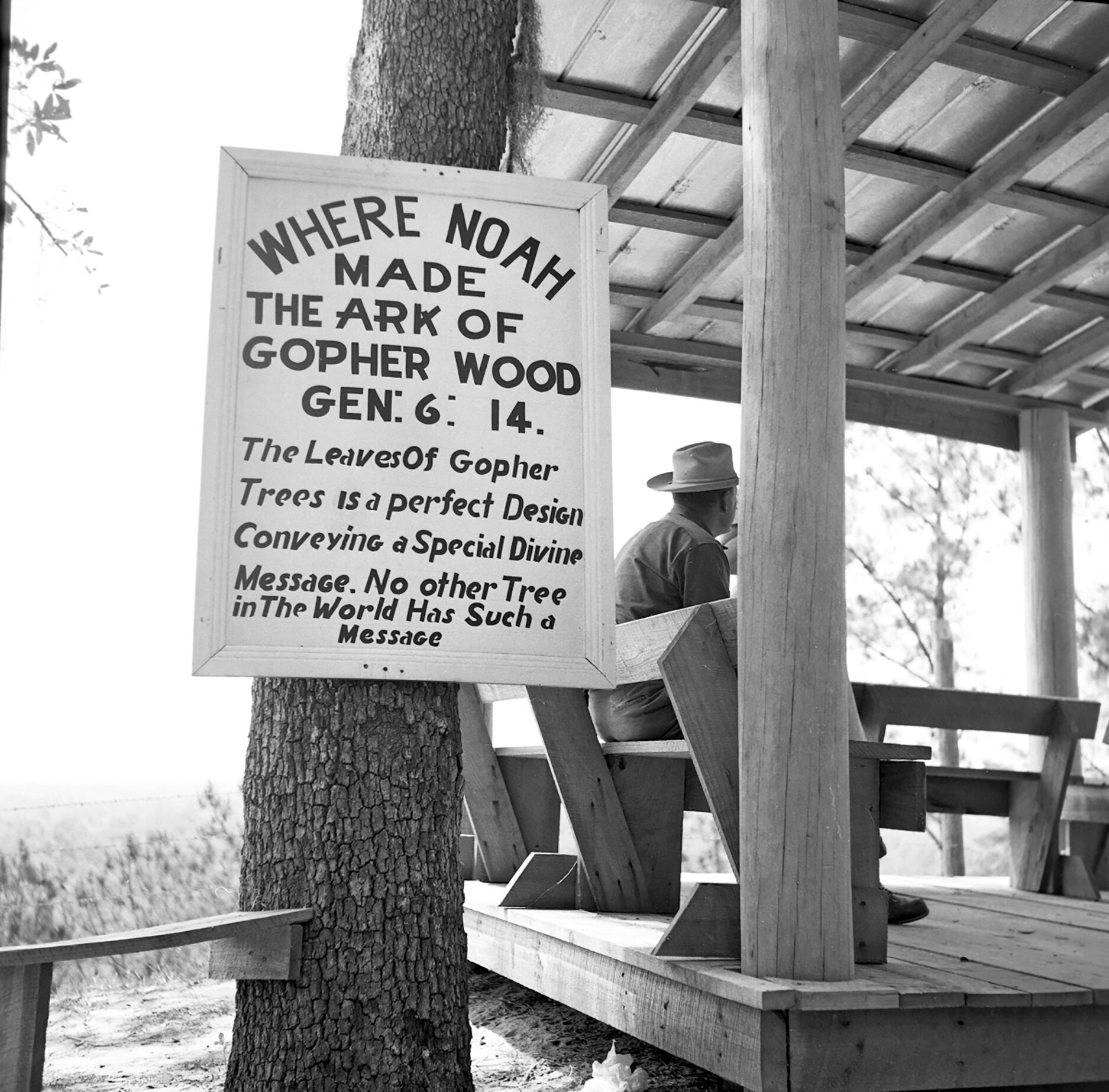

In 1956, E.E. Callaway’s Garden of Eden opened to the public. For $1 plus 10 cents tax, visitors could walk the trails overlooking the Apalachicola River and see signs marking the Birthplace of Adam; the Site of Adam and Eve’s First Home; Where God Discovered Adam Was Lonely; and Where Noah Made the Ark of Gopher Wood. Images courtesy of the State Archives of Florida/Red Kerce.

In Callaway’s version of the Great Flood, Noah and his family floated down the Apalachicola and out to sea, drifting for 150 days, until landing in Turkey. “Noah and his family did not know that they had landed on Mt. Ararat, so far from their original home in Liberty County, Florida,” Callaway wrote.

After Callaway made his discovery, he built a roadside attraction, with billboards along the highway counting down the miles to the Garden of Eden. Travelers paid $1 plus 10 cents tax to walk the trails overlooking the Apalachicola River. Hand-painted signs marked the Birthplace of Adam; the Site of Adam and Eve’s First Home; Where God Discovered Adam Was Lonely; Where Noah Made the Ark of Gopher Wood.

Callaway’s Garden of Eden was open to the public by 1956; within the next few decades, the Florida torreya would be added to the endangered species list. Today, The Nature Conservancy is maintaining that land as scientists and landowners work — sometimes with conflicting approaches — to preserve and protect the Florida torreya, one of the world’s rarest trees.

The Atlanta Botanical Garden property in Gainesville, Georgia, keeps a “safeguarding collection” of Florida torreyas, as well as cryogenically stored seeds. ABG staff monitor their torreyas in hopes that some of the trees will prove resistant to the fungus that has plagued the trees for over half a century.

In the 1830s, an amateur botanist named Hardy Croom was wandering along the banks of the Apalachicola when he noticed an unfamiliar tree growing in dense groves on Aspalaga Bluff. “A tree from 20 to 40 feet high, and from 6 to 12 inches in diameter. It grows plentifully, on calcareous knolls,” he wrote in 1834. Croom took samples and mailed them to the botanist John Torrey, who determined that this tree was an entirely new genus of conifer. Croom suggested the tree be named after Torrey. Decades later, at Torrey’s funeral, members of the Torrey Botanical Club (now the Torrey Botanical Society) brought cuttings from a torreya tree and laid them across his coffin.

In his 1875 essay “A Pilgrimage to Torreya,” Torrey’s student Asa Gray, who would later be referred to as the father of American botany, wrote that very few botanists had seen the torreya growing in the wild, and he “was desirous to be one of the number.” Even Torrey himself never saw one in the wild, though he traveled to Florida in 1872, a year before his death, and saw a Florida torreya growing in a garden in downtown Tallahassee. Two years after Torrey's death, Gray planned to “make a pious pilgrimage to the secluded native haunts of that rarest of trees, the Torreya taxifolia.”

An amateur botanist named Hardy Croom saw a conifer like no other growing on Aspalaga Bluff. “A tree from 20 to 40 feet high, and from 6 to 12 inches in diameter. It grows plentifully, on calcareous knolls,” he wrote in 1834. Croom shared samples with the botanist John Torrey. The new genus was named Torreya. Intense logging devastated the population and as early as 1885 the tree seemed “destined for ultimate extinction.” Photo taken at Torreya State Park in Liberty County.

When Gray arrived in the Panhandle, he found few specimens, and the ones he saw disappointed him: “I saw no tree with a trunk over 6 inches in diameter,” he wrote. He returned to the steamboat as night fell, bringing with him a bundle of torreya seedlings, hoping that one of them might be planted at Torrey’s grave in Stirling, New Jersey. On the return voyage, the steamboat passed Aspalaga Bluff. Only half a century had passed since Croom had first seen the torreya growing there, but Gray noted that Aspalaga Bluff was bare; the plentiful torreyas that once lined its banks had been cut down and used as fuel for steamboats like the one carrying him upriver.

Torreya seedlings

This might have been the first major blow to the torreya population; in the years to come, they would be harvested and used as shingles, fence posts, and Christmas trees. By the middle of the 20th century, torreyas were further threatened by a mysterious fungus. Today, ailing trees are still unable to sexually reproduce; instead, they send up spindly shoots from the ground — none of which reach maturity. The fungus covers their thin, stunted trunks in cankerous sores.

Lately, increasingly severe — and frequent — hurricanes and tropical storms might be the biggest threat to the torreya. Though the torreyas themselves are often left standing in the wake of a storm, they depend on the shade of the canopy and are scalded by direct sunlight when larger trees fall. According to a report from the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agriculture Sciences, the Florida torreya has declined 99% from an estimated population of 357,500 in 1914 to approximately 1,350 in the 1990s. The torreya's population has dwindled to an estimated 400 to 600 trees.

In 1885 the botanist A.W. Chapman published an essay about the Florida torreya in which he seems to consider the tree already on its way out: The torreya “is destined,” he wrote, “to ultimate extinction.”

“For some reason, it’s difficult to be impassive about trees,” Jordan Kisner writes in an essay on the quaking aspen. “Since the Tree of Life, a mytheme common to ancient religions from every corner of the world, we have been telling stories about trees to tell stories about ourselves, and so it’s hard to resist our desire to make the tree a story, to make it our story, to make it us.”

Before I ever saw a Florida torreya, I felt a strange kinship with this tree that seems so chronically out of place, unsuited to its habitat, and which for decades now has been unable or unwilling to reproduce. Whenever my husband and I imagined our future children, I made constant, silent, mental calculations, visualizing our child’s lifespan alongside scientists’ projections for warming temperatures, rising seas, and stronger, more frequent storms.

Scientists estimate that the Florida torreya has existed for 165 million years. In its ancient age — and its current precarity — the torreya seems emblematic of deep time as well as our present moment, when the damage humans have wrought, in our relatively short existence, threatens the survival of many similarly ancient species.

Chris Larson admires a Torreya tree at her property in Mossy Head.

Today, the Florida torreya is at the center of a debate between conservationists and local landowners, between those who favor restoring the tree in its native habitat and those who advocate for assisted migration, or manually evacuating the tree farther north. A group called the Torreya Guardians has been working to plant torreya seeds and seedlings in states such as Michigan and New Hampshire, in hopes that the tree might fare better in cooler climates. Their “free-planting experiments” involve planting seeds directly into forests — mostly onto their own land.

Opponents worry this could introduce the fungus attacking the Florida torreya to other vulnerable tree species. Advocates of assisted migration argue that the torreya doesn’t have time for the painstakingly slow approach of native habitat restoration favored by most scientists and conservationists. When I talked to one proponent of assisted migration, she warned me that the controversy surrounding the Florida torreya was too big and too messy to write about, too contentious. She urged me to write about some other tree, some other place.

But whenever I tried to put the torreya out of my mind, I thought of Callaway and his rewriting of Genesis on the land around him. Callaway is often portrayed as a prototypical “Florida Man,” a wacko preaching a brand of off-kilter biblical literalism. But lately, I’ve felt drawn to people like Callaway, and to the places where people like him have sensed something sacred, where the space between heaven and earth — and time itself — seems to grow thin. I’ve wondered what it might mean, in an era of environmental collapse, to look for the divine in nature. Perhaps more than anything, I’ve been compelled to see what I might learn from a tree that hovers somewhere between the past and the present.

I was three months pregnant when I planned a trip to the Panhandle. I would leave on March 20, 2020, stay in the White Squirrel Inn in Quincy, Florida, and finally see the torreyas in person. Of course, you know the rest. A week before my scheduled trip, the coronavirus was declared a global pandemic, and I emailed cancellations and apologies, promising that I would make the trip during maternity leave. I could not conceive of the pandemic lasting as long as September or October. I tried to think positively: I’d heard the forests in which the torreya grew were among the few places in Florida where the leaves change color in the fall.

When Trey Fletcher was growing up in the 1980s, fearful of impending nuclear war, he always imagined he would retreat to Torreya State Park “when the shit hit the fan.” Fletcher knew the park well; there was clean water in abundance, and he could hunt for food and hide out in the forest’s deep ravines and lush vegetation.

Fletcher grew up in Gadsden County, Florida, hearing about the Florida torreya, an otherwise ordinary tree that was central to the story that had defined his hometown for over half a century. As a child, Fletcher saw Callaway’s book, In the Beginning, displayed prominently on the bookshelf at a friend’s house, and wondered often about the author’s theory that the Garden of Eden was just a few miles down the road.

He told me many of the people he grew up around couldn’t necessarily identify a torreya, but they all knew the myth: Adam and Eve once made their home here along the Apalachicola River, and Noah had used the wood of the Florida torreya to build his ark.

Fletcher left home to study interdisciplinary ecology at the University of Florida. When people asked him what he wanted to do with his master’s degree, he told them he wanted to go back home, to work to preserve that particular environment. Now Fletcher works as a horticulturist and curator at the Atlanta Botanical Garden, which houses the largest collection of Florida torreyas outside of the trees’ historic natural range.

It made sense that, as a child anticipating the apocalypse, Fletcher would have thought of Torreya State Park. According to Callaway, the torreya had helped humanity survive before. Surely the tree could do it again.

“But the apocalypse,” Fletcher says, “got to the park first.”

Trey Fletcher in front of his family home in Gadsden County, Florida. Fletcher works for the Atlanta Botanical Garden and often serves as a bridge between conservationists and local landowners.

When Hurricane Michael hit the Panhandle in 2018, Fletcher’s sister called from Gadsden County, where she lives in the house their great-great-grandfather built 150 years ago. She was frantic; the rain was coming through the walls. As soon as the roads opened, Fletcher drove home, checking on his mother and sister before heading toward Torreya State Park. Fletcher made it as far as Aspalaga Bluff before being blocked by debris.

“The giant trees that had lined the road were all knocked down,” Fletcher recalls. “The air was redolent with the smell of tree sap. Ancient trees had been ripped up and cast like matchsticks into the bottoms of ravines.”

Fletcher says he had expected he might cry, or scream, or tear his hair out when he saw the devastation the hurricane had wrought. But when he arrived, he says, “It was overwhelming. It was too much. It was just a void.”

Fletcher was one of several people I talked to who would begin to tell me about their property, or their favorite hiking trail, and only halfway through seem to remember — as if shocked from a bad dream — that this place no longer exists, at least not in the way they remember it. Fletcher would shift from the present tense to the past, correcting himself as he recalled the ways Hurricane Michael had changed the landscape, perhaps irrevocably.

In our conversation, Fletcher was careful to steer clear of the controversy surrounding assisted migration, but he says he would like to see the torreya restored in its natural habitat. Although he is quick to note that he holds the accepted position of the scientific community, it seems Fletcher’s support for native habitat restoration comes from a more personal place. “I’m from there,” he says, “and I have such an affection for the place. I’d love to see the tree restored in that environment.”

Fletcher at Aspalaga Bluff. “As an ecologist, you get called a tree-hugger a lot. But ecology is ultimately about people; helping people deal with the changes that are coming,” Fletcher says.

The Atlanta Botanical Garden keeps a “safeguarding collection” of Florida torreyas, as well as cryogenically stored seeds in its Gainesville, Georgia, facility. ABG staff monitor their torreyas in hopes that some of the trees will prove resistant to the fungus. These could then be cross-bred, boosting the trees’ resilience against the invasive fungus that has plagued them for over half a century.

Much of Fletcher's long connection to the torreya tree feels serendipitous: “According to the myth,” he says, “Noah supposedly built the ark out of the Florida torreya. And now we’ve essentially built an ark for these trees at the Atlanta Botanical Garden.”

But landowners on the Panhandle are often wary of the work of conservation organizations. Some keep the torreya trees on their land a secret, to avoid attracting attention or because they believe the government might take their land away. In Fletcher’s roles as both a scientist and a local, he hopes he may be able to heal some of the divides between the scientific community and the local landowners, whom he sees as crucial allies in the fight to save this tree.

Fletcher told me about meeting with a group of scientists and locals in a restaurant just outside Torreya State Park. It was a hole-in-the-wall place with no sign outside, and Fletcher found himself seated between the two groups, serving as a kind of translator for each side.

“It’s a cliché you hear all the time,” Fletcher says, “that to get people involved in conservation you have to make them feel like you care about them. But I’m not just trying to make people feel like I care about them. I actually do. Yes, I’m interested in the trees and the conservation efforts, but I’m also interested in the people themselves.

“As an ecologist,” he continues, “you get called a tree-hugger a lot. But ecology is ultimately about people; helping people deal with the changes that are coming.”

For as long as humans have written about the Florida torreya, it’s existed only along a small stretch of the Apalachicola River. But the tree likely grew farther north until the ice age, when glaciers pushed the torreya, and many other species, farther south. When the glaciers retreated, the Florida torreya was left behind, trapped in cool, shady steephead ravines for the last 10,000 years.

This theory explains the presence of other plants, like mountain laurel and flame azalea, that are found in this area of the Panhandle, even though they typically live in the higher elevations and cooler temperatures of the Appalachian Mountains. Proponents of assisted migration argue that the Florida torreya’s true native habitat is much farther north than a tiny stretch of the Florida Panhandle. The trees are not able to migrate fast enough on their own, they say, and are stressed by an increasingly warm climate.

“Assisted migration is necessary,” Chris Larson told me right away. When she and her husband, Robert Larson, bought Shoal Sanctuary, their 115-acre property in Mossy Head, Florida, 20 years ago, the land had been deforested. The Larsons are cultivating a diverse forest, and they’ve planted 14,000 trees so far, including 50 redwoods and dozens of Florida torreyas.

The Larsons, who consider themselves affiliates of the Torreya Guardians, are two of many volunteer planters growing torreyas on private land. On their website, Torreya Guardians volunteers catalog their efforts in incredible detail, comparing plants grown from seeds or cuttings; in flowerpots or coffee cans with the bottoms cut out; watered with irrigation systems or “ambient rainfall”; surrounded by mothballs or nibbled by groundhogs.

Chris Larson in her planting shed at Shoal Sanctuary. At their preserve in Mossy Head, Chris and her husband, Robert, have planted more than 14,000 trees, including dozens of Florida torreyas.

The Torreya Guardians website acknowledges that “the concept of assisted migration will directly conflict with established conservation principles.” But, they argue, “the risk associated with doing nothing is greater than the risk associated with intervening.” Hurricane Michael seemed to add some urgency to their work. To them, moving the torreyas north might be the trees’ last hope for survival.

The Torreya Guardians seem to practice an almost religious devotion to the torreya, posting photographs of each plant, documenting their halting progress over the years: They excitedly note good luck planting torreya seedlings alongside ginger root; sprouts emerging from rodent droppings are hailed as “miraculous.”

When she first went to see the property in Gadsden County, Donna Wright stood on a high ridge and looked down over a creek, its sandy banks winding off into the distance. “I just couldn’t believe that I could own something that beautiful,” she says. Shortly after she purchased the land, Wright’s friend, a biologist, came to see it and identified several torreyas growing on the property. Soon Wright was getting calls from the Atlanta Botanical Garden. Scientists wanted to see her trees.

At first, Wright was enthusiastic about cooperating with conservationists. She even delayed a scheduled double mastectomy to meet with the Atlanta Botanical Garden representatives in February 2010. “I scheduled the procedure around their visit because I thought, ‘Well, if I miss this, I might as well be dead,’” Wright says.

Atlanta Botanical Garden staff members walked Wright’s property and took samples of her trees. She says it is hard to describe what a moving experience that was, but she soon began to feel disillusioned. “The group gets bigger, committees take over, and soon I’m a long way from the scientists themselves.”

Donna Wright on her property in Gadsden County, Florida. All of the torreyas on Wright’s property, including the one pictured above, show signs of the fungus threatening torreya populations across their tiny range. Wright’s mother died from breast cancer, and Wright’s experience as a survivor of breast cancer is intimately linked to the trees she cares for: Florida torreyas often grow alongside the Florida yew, which contains taxol, a compound used to treat breast cancer, as well as other cancers and diseases.

All of the torreyas on Wright’s property show signs of the fungus that is wiping out torreya populations across their tiny range. But, she says, the trees are beautiful. Wright’s mother died from breast cancer, and Wright’s experience as a survivor of breast cancer is intimately linked to the trees she cares for: Florida torreyas often grow alongside the Florida yew, which contains taxol, a compound used to treat breast cancer, as well as other cancers and diseases. Though she cares deeply for these trees — her voice often breaks with emotion when she talks about them — Wright has distanced herself from organized conservation efforts.

“People’s appreciation for this tree is woven into their being,” Wright says, “and then, in come the scientists, and it’s two different worlds. If I were doing this work, I’d go to a landowner and ask them why they love the torreya, why they find meaning in it. People here get so frustrated with conservationists. When they hear ‘conservation,’ they close the door.

“I have had to back up, to maintain the sacredness of it all, the joy, and quietly know that I’ve kept the torreyas safe. I’m still keeping them safe,” Wright says. “And my reward is that I get to be alone in the woods with a plant that’s on its way out. Not everybody gets to do that.”

After Hurricane Michael, Wright trained her German shorthaired pointer, Tucker, to sniff out torreyas that might be trapped under debris.

Road access to Wright’s property has been blocked ever since Hurricane Michael, and she says she hasn’t been able to visit her 13 acres as often as she’d like. Across her property, Hurricane Michael toppled many larger hardwoods, depriving the landscape of their protective shade. After the hurricane, Wright began training her German shorthaired pointer, Tucker, to sniff out torreyas that might be trapped under debris. Wright predicts her torreyas, already fragile, risk being scalded by the increased sunlight. But when she thinks about her land, even in its damaged state, she says, “God lives there. When you’re in the woods, everything behaves as it should.”

Wright told me she often weighs habitat restoration efforts against the threat of climate change: “Maybe we’re helping a little bit,” she says, “but the earth is going to re-create itself through climate change. By not participating in organized conservation efforts, I haven’t hurt a thing. At all.”

When I asked Wright about her role as a landowner in this work, she paused for a moment. “I don't know that any of us own land, really,” she says, “but we pay a lot of money to shoulder the burden of stewardship. And in that way, the trees are under my stewardship for right now. And the sense of responsibility or love is deep. It's almost intimate. I walk in the woods and I walk past them and for now, for now, they're mine. I have this little teeny window. My ownership of this land will be so short when you compare it to all of time. But for right now they're mine.”

In the long list of plants and animals facing similar challenges and dwindling numbers, it might seem hard to justify the amount of attention and resources that the Florida torreyas command. Focusing on one ailing species often feels like a choice to ignore another. Compared with the Florida yew, with its cancer-fighting potential, or the gopher tortoise, whose deep, winding tunnels protect other species fleeing fires, it’s hard to know what the Florida torreya offers — what it means — other than its role in a story projected onto it.

I’ve wondered how Callaway’s story, of the torreyas’ role in ushering the Earth’s creatures to safety from the Great Flood, might have shifted meaning in today’s context, when the tree is just one of many species that now need saving — from rising seas and rising temperatures, increasingly frequent and dangerous storms, melting ice and degraded soil.

Callaway contained often contradictory multitudes. Born in Weogufka, Alabama, the son and grandson of Baptist ministers, Callaway left the church after refusing to repent for attending a dance; although he saw himself as progressive and represented the NAACP as a prosecutor, he also held a wide variety of racist beliefs. In 1936, he ran for governor as a Republican, when Florida was a heavily Democratic state; and though he fell in love with the discoveries of scientists like Charles Darwin and Thomas Edison (Callaway’s namesake), early in life, he struggled to reconcile that love with the religious conversion he experienced in his later years.

When I tried to get a sense of Callaway’s life, I spoke to Marilyn Ray Smith, whose father was Callaway’s first cousin and lifelong friend. Smith, who has lived in Boston since the 1960s, sees the Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson, another Alabamian with a passion for the environment and storytelling, as a vision of who Callaway might have become under different circumstances. “Elvy had a very active, fertile mind and no place to go,” Smith says. “History books are full of people like this, who live in isolated communities, who don't march to the same drum, who have differences, and they often end up being quite eccentric. And so the neighbors think they're crazy. But you know what? He wasn't totally crazy. That is a spectacular spot.”

Because of Callaway, Smith says, the Garden of Eden was saved.

David Printiss, the Nature Conservancy’s north Florida Conservation manager, points to the Garden of Eden tract of the conservancy’s Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve. An anonymous $1 million donation in 1982 allowed the Nature Conservancy to buy the former roadside attraction.

There were several proposed developments for the Garden of Eden site, including a Garden of Eden-themed amusement park, but none of them stuck until an anonymous $1 million donation allowed the Nature Conservancy to buy the land in 1982. Today the Garden of Eden tract makes up about 20% of the 6,295-acre Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve. The ABRP sits on Garden of Eden Road and maintains a hiking loop through the original land maintained by Callaway. At the trailhead, a simple metal sign states “Garden of Eden Trail.”

Few of the preserve’s visitors know Callaway’s history, says David Printiss, the Nature Conservancy’s north Florida conservation manager. “That's ancient history, as it were.”

The Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve is focused on longleaf pine habitat restoration and the preservation of species-rich slope forests and seepage streams. When the Nature Conservancy began its work in the Panhandle, much of the land they’d purchased was badly damaged through heavy industrial treatment, but the Garden of Eden tract was relatively unscathed. Nature Conservancy staff were able to collect seeds in the Garden of Eden tract that helped restore the rest of the preserve, as well as the neighboring 13,735-acre Torreya State Park. Printiss told me he thinks of the Garden of Eden tract as “the Garden of Eden of longleaf pine diversity.”

Printiss tells me that the steephead ravines in which torreyas usually grow are why the Nature Conservancy came to this area of the Florida Panhandle. But where they’ve really made a name for themselves, he says, is in restoring the uplands through prescribed burns, reintroducing fires that are an integral part of the forest’s health.

For organizations like the Nature Conservancy working to restore native habitat, the torreya is just one of many endangered species that make up the larger ecosystem; here, there are also gopher tortoises, eastern indigo snakes, Florida pine snakes, Apalachicola rosemary, and the Florida yew. Printiss at Alum Bluff on the Garden of Eden tract.

On the ABRP website, photos documenting the damage done by Hurricane Michael show roofs ripped off offices and classrooms; shade cloth hanging loose from the wiregrass nursery; volunteers picking up bits of insulation scattered across the preserve. Along the Apalachicola River, photos show nearly every tree ripped clean of leaves. Two years later, in 2020, the Garden of Eden Trail was one of the few trails reopened to the public.

“In many areas the trees are now underneath 10 feet of debris,” Printiss says. “In geologic time, hurricanes would have come through here and the trees would have been able to sustain that. But they're highly stressed; they're not reproducing.”

When I ask Printiss how climate change might alter this area, he says, “Some things are obvious: sea level rise, things are going to be underwater; but others are like, what's it going to do to fire return intervals and soil moisture?”

For organizations like the Nature Conservancy working to restore native habitat, the torreya is just one of many endangered species that make up the larger ecosystem; here, there are also gopher tortoises, eastern indigo snakes, Florida pine snakes, Apalachicola rosemary, the Florida yew. Meanwhile, the very idea of restoration feels fraught: How do we restore a habitat to an ideal image of its past, while the future of that habitat seems increasingly uncertain?

Land scorched by prescribed burns near the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve. The Nature Conservancy has been restoring the uplands through prescribed burns, reintroducing fires that are an integral part of the forest’s health.

An Apalachicola riverboat captain named Gill Autrey first heard about E.E. Callaway from a mysterious passenger, a woman who kept her signed copy of In the Beginning wrapped in aluminum foil and held it with gloved hands. Autrey tracked down a copy for himself, and he told me that the book made him a believer. “You mean to tell me the Garden of Eden was in Iran or Iraq?” he laughed. “Give me a break.”

I asked Autrey if he knew anyone who had been there when it was the Garden of Eden.

“Well, it still is,” he says, sounding befuddled. “It still is the Garden of Eden.”

At first, I thought he meant that the Garden of Eden tract had been preserved, that the 3.75-mile Garden of Eden Trail still winds its way along the bluffs there, much as it did during Callaway’s time. But later, listening back to the recording of our conversation, I realized that wasn’t what he meant. I’d betrayed my skepticism with the use of “was,” that single, past-tense verb. My question, of course, implied that the Garden of Eden “wasn’t” any longer.

In the opening pages of In the Beginning, Callaway uses the past and present tenses to introduce his subject: “the Garden was and is a fact, and was and is located between Bristol and Chattahoochee, Florida. … ” Callaway’s language suggests the Garden of Eden has some essentially inherent, unchanging nature, which I heard from so many of the locals who spoke with me: a sense that the land they lived on was special, magical, somehow set apart.

Like Callaway, I grew up a preacher’s kid in the South, though with a very different kind of religion. In my father’s faith, the Bible was understood symbolically, not literally. I grew up thinking of the story of Adam and Eve’s banishment from the Garden of Eden as a metaphor revealing humanity’s essential alienation from both God and the natural world.

But in Callaway’s version of Genesis, paradise was not some distant, perfect land, guarded by angels with swords of fire, and it was not a mere metaphor, either. It was a real place, just down the road, that anybody could visit. There is a particular moment of Callaway’s televised interview that I’ve replayed on YouTube dozens of times. Sitting on the bluffs overlooking the Apalachicola River, the sunlight glinting on the broad stretch of water churning behind him, Callaway made a proclamation: “I’ve studied the Bible and walked these woods, and I can prove that this is paradise.”

Adam and Eve might have been banished from the Garden, but the rest of us were not, so long as we could accept that paradise might be the marred, imperfect ground beneath our feet.

Aspalaga Bluff in Gadsden County.

By the time my son was born in September, I should have learned how little faith to put in plans. But I was surprised to give birth in a mask; surprised by how quickly we abandoned our birth plan; surprised by the emergency Caesarean section. I was surprised when I contracted an infection and spent weeks receiving daily antibiotic infusions while wearing a wound VAC. I was surprised when I found myself unable to walk around the block, much less travel, and I had to cancel the second trip I’d planned to meet the torreya in the Panhandle.

When I wrote Donna Wright to let her know, attaching a photo of my infant son, wrinkled and tiny in his hospital-issued hat, she sent me photos of her torreyas, their green needles shining in the sun. They seemed like all the world I could not get to, conjured up in a single image.

When I finally saw a Florida torreya, over a year after my originally scheduled trip, it was not in Florida at all, but in Asheville, North Carolina. In 1939, the botanist Chauncey Beadle gave several Florida torreya specimens to the Biltmore Estate. The torreya we found stood near a pond, its limbs rustling in the cool mountain breeze as tourists walked by, unaware of the tree’s plight, the arguments it has inspired, or its precarious hold on the future. The torreya was larger than I’d expected. In 2015, the Torreya Guardians surveyed the torreyas growing at the Biltmore, and recorded diameters of 46 inches and 40 inches for this tree’s two trunks. The tree looked healthy, unmarred by fungus or disease. It looked right at home.

In my interviews with people trying to save the torreya, I noticed that some of them seemed hopeful for the tree’s future, but many of them did the work without much hope at all. Instead, the work itself was a remedy against despair, against assuming that all is already lost.

What we witness now is not the end of the world but the end of many worlds, perhaps more worlds than we knew we had to lose: the world of the American chestnut, the whitebark pine, the maple-leaf oak, the eastern hemlock, and one day, perhaps very soon, the world of the Florida torreya. But as the torreya’s extinction has become arguably more likely, people devoted to the tree have become less willing to admit it. They are compelled, instead, to build whatever arks need to be built.

When I ask Wright whether she has hope that the torreya could make a comeback, she says the tree’s future is in the hands of the scientists at the Atlanta Botanical Garden. “Its DNA is with them,” she says. “Knowing this makes me feel a little bit eternal. … The fact that science will bring this to fruition is a beautiful marriage to me, not a conflict; there’s great faith on both sides. … Yes, I have great hope. I know something about tomorrow.”

Martha Park is a writer and illustrator from Memphis, Tennessee. Her work appears in Guernica, Granta, Ecotone, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. She has written about pregnancy during the pandemic and how politics, religion, history, and science collide at the Ark Encounter for The Bitter Southerner.

Johnathon Kelso is an editorial photographer working on long-form projects related to history and race in the American South. Raised in the Florida Panhandle, Kelso now lives with his wife and three children just outside Atlanta in Decatur, Georgia. In his work for The Bitter Southerner, he has photographed the family of WWII fighter pilot Eugene Bullard and his brother Hector Bullard, families in the Ellis Island of the South, and the generational impact of lynching sites in six Southern states.