~ In Partnership with Americana Music Association ~

Acclaimed photographer and filmmaker David McClister has been documenting the rise of Americana music for more than a decade. In the first in a three-part series celebrating AMERICANAFEST, McClister shares what the festival’s signature event, the Americana Music Honors & Awards, has looked like through the lens of his camera and the artists he’s captured with it.

Words & Photos by David McClister

May 30, 2024

I first started going to AMERICANAFEST in Nashville in 2012. The festival and conference had already existed for a decade by that point, but it still felt like it was in its infancy when I showed up that year. There were no television crews yet, but you could already feel the growth, the change in the air. They’d just expanded the event to five days — there were seminars for young artists and industry folks during the day, and live shows all over town each night — but the centerpiece of the week was the Americana Music Association Awards Show at Ryman Auditorium. Jed Hilly, executive director of the Americana Music Association, had reached out and asked if I would take photos of the rehearsals for the show. And after a few years of gently nudging the organizers, I eventually convinced them to let me shoot portraits of the artists backstage during the show, too.

The Ryman is an iconic, historic venue, and for some of the younger artists, this was often their first time playing there. From the awards show’s very beginning, Buddy Miller led the house band, which often included legendary figures like Don Was and Larry Campbell. So it could be intimidating for a young artist, and that’s even before you take into consideration that everyone knew they were preparing to perform for an audience filled with their peers. Artists would often come to those rehearsals with a strange mix of anxiety and excitement, which was made all the more surreal by the fact that there could be tour groups walking through the auditorium while someone like Bob Weir or Chris Isaak was rehearsing onstage.

Bob Weir (2016)

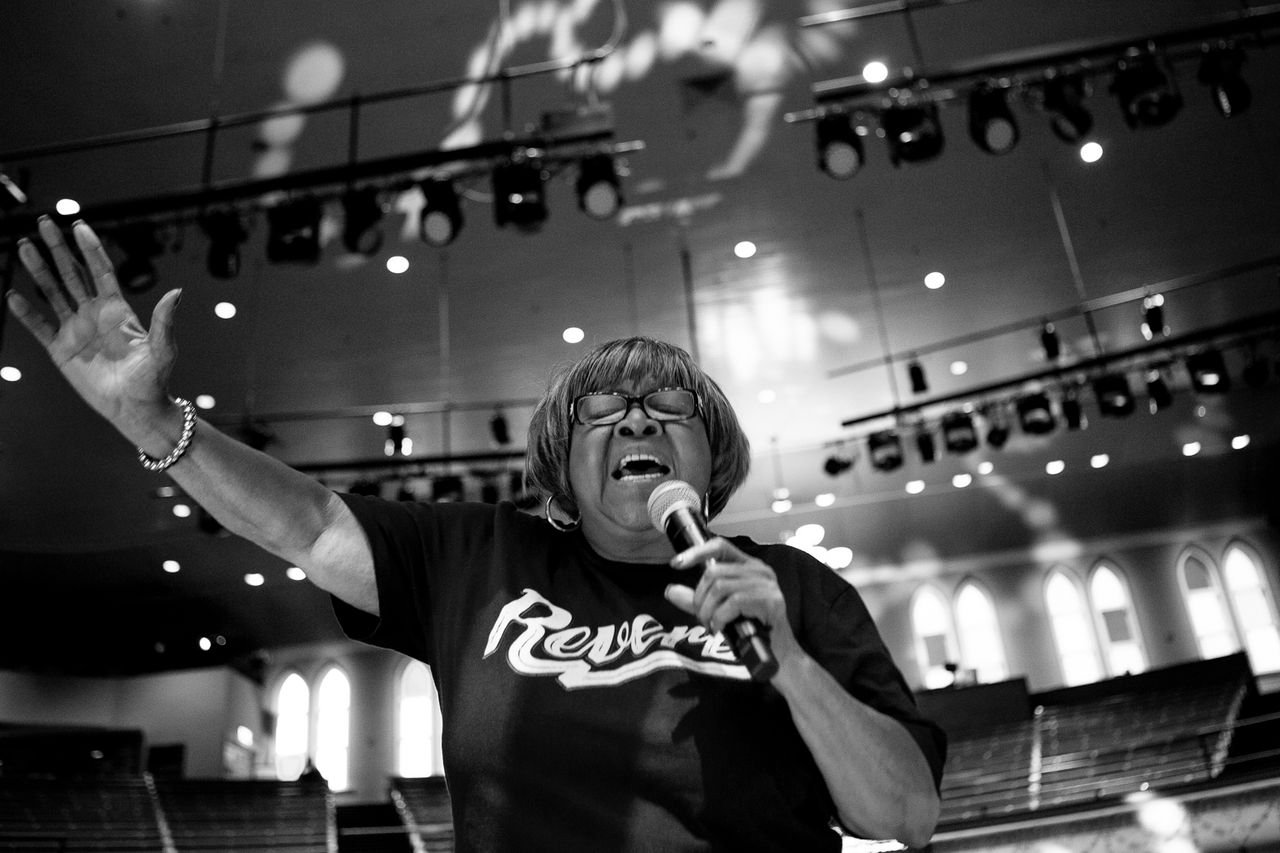

This impromptu audience could change the tenor of a rehearsal. For some of the artists, sound check was like a typical sound check, but for many, once they noticed a crowd of people watching, the performer in them would take over even though they were performing for an audience of no more than a handful. Others, often the older artists, would see me and my camera documenting the moment and cater their performance directly to the camera. They’d turn toward me and accentuate their playing, really letting it rip as if they were in front of a full house. I remember that being the case for legends like Irma Thomas, Mavis Staples, Elvis Costello, and Stephen Stills, but also for a few of the younger performers, like Alynda Segarra of Hurray for the Riff Raff. They understood the power of an image — of capturing a moment — and how lasting that impression could be.

Hurray for the Riff Raff, 2017

Mavis Staples, 2019

Jed also knew just how important and special documenting these rehearsals could be — not only for the Americana Music Association archives but for posterity as well. I was often there for unique and special moments when legends were reunited or introduced for the first time. Robert Plant and Patty Griffin’s rehearsal felt like one of those times. They had been a couple but had just recently split. Patty is a shy and very private person. I wasn’t sure what to expect or even if I should shoot the session. Plenty of times, I’ve put my camera down when I felt it was not the right time or place to shoot. But their music chemistry was self-evident from the very first notes. The joy, the deep respect, the friendship, all came through in those photos. Then there was the notoriously difficult Van Morrison, who played the awards show in 2017. He didn’t really do much of a sound check — I don’t know if he even opened his mouth — but I had a sense this was likely to be the case, so I was ready and got in place quickly, anticipating where the best angle might be. I was able to take exactly one photo of him before someone from his team sternly told me, “No photos.” Fortunately, that single photo was a keeper.

Patty Griffin & Robert Plant, 2014; Van Morrison, 2017

Anticipating where to be on the stage for each artist’s rehearsal comes down to instinct, and maybe a little serendipity. It’s simply a feeling that I respond to — a quiet voice, maybe — telling me where I should be, if I should sit or stand, if I should avoid the performer’s eyeline or get right in it, all while moving about as if I’m nothing more than a shadow on the stage or another piece of equipment being moved from one place to another. If no one notices that I’m there, then I’m doing my job correctly.

Shooting backstage portraits is its own kind of unique challenge. The Ryman is an old theater, with very little backstage area. The large house band shares one small dressing room, and then, just before the show begins, I transform a tiny production office on the other side of the stage into a makeshift photo studio. That shot of all the guys in Old Crow Medicine Show literally takes up the entire width of that room.

Old Crow Medicine Show, 2017

A typical “session” would last five to 10 minutes, usually taking place just before an artist went onstage or right after they came off. At that point, performers would generally be so pumped for or from their performance that I’d try and take advantage of this creative energy. It’s an incredible high to witness. My approach is always “Let’s play!” Once they’re in place, I look for an opening for the dance to begin. I like to move quickly and keep moving. My assistants and I have a shorthand, a look, a gesture, so we can adjust quickly to what’s working, what the artist is doing, and take advantage of it. Many of the photos shown here — Allison Russell, The War & Treaty, Sierra Ferrell, Charley Crockett, Lilly Hiatt, Lukas Nelson — are great examples of this spontaneity at work.

The War & Treaty, 2019

Sometimes no direction is necessary. My session with John Prine and Bonnie Raitt is one of those. Those two had been such close friends for so long and had meant so much to each other that I felt my job was just to get out of the way and let it happen. Anything I might say would just break the magic.

The same kind of thing was true with Our Native Daughters. Rhiannon Giddens has been such a key figure in the Americana scene over the past decade, probably doing as much as any single person to help broaden not only the scope of the genre but also expand its audience. Our Native Daughters is, in many ways, a manifestation of this, so capturing the chemistry and excitement between her, Allison Russell, Amythyst Kiah, and Leyla McCalla was really mostly about just letting them be themselves in front of the camera for a few minutes while I tried to be as invisible as possible.

Our Native Daughters (Rhiannon Giddens, Leyla McCalla, Amythyst Kiah & Allison Russell), 2019

Every once in a while, I was able to get out of that tiny production office for a quick photo shoot somewhere else in the building. I’ve been going to the Ryman for so many years now that I’ve discovered many of its hidden secrets. One day, I took Taj Mahal to a seldom used back stairwell that leads down to one of the side streets. As I’d hoped, the light was pouring in the windows, making the place feel like an old country church. I asked Taj if he would play his guitar a bit, and with that, the dance began. I was playing with the light, suggesting he move this way or that, trying to simultaneously do my job and savor a little bit of the private show that Taj was giving to his audience of one.

Shooting both the rehearsals and the portraits over the past 12 years has given me a unique window into AMERICANAFEST. In that time, I’ve seen artists like Brandi Carlile, Jason Isbell, and Margo Price rise from modest successes to outright stars. I’ve also seen the way the festival and the entire genre has grown more diverse musically and demographically. The respect for the music’s elder statesmen — people like Mavis and Irma and Bonnie and Robert Cray and Lyle Lovett — that’s always been a part of Americana is now matched by an open-minded appreciation for a wider swath of newer artists. That I’ve been able to have a backstage pass to all this feels like an amazing stroke of luck that I can only hope continues for another 12 years.