“It’s not a house, it’s a home.”

— Bob Dylan, “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest”

Story by Mary Warner

Photography by Maude Schuyler Clay & Langdon Clay

Maudie and Langdon stayed at my house just a few months after I bought it with savings intended for a wedding that never happened. They were in town for their art opening and I was in Italy for the first time. I told them to stay at my place. Maybe they could break it in. Books were stacked everywhere at the time and many of my things were still in boxes, but I had a bed, a beautiful view of downtown and a kitchen. Everything they would need for a weekend in Atlanta.

When I came home I found several scribbles from Maudie on pieces of paper throughout the house. One on a book she left behind to replace the one she borrowed. Another on a new tea kettle, and one stuck to an unfamiliar bag of coffee. The last one I found was on a stack of books: "Langdon can help you build shelves for these next time we come to town."

They had come to my house from Mississippi, the Delta to be exact. Unlike Atlanta’s multimillion (and growing) population, Sumner, Miss., which the couple called home, accounted for 317 people (and shrinking) in the 2010 census. To me they were just Maudie and Langdon, an easygoing pair who had welcomed a questioning Southerner — namely, me — into their Delta home almost a decade before.

To the rest of the world, they are Maude Schuyler Clay and Langdon Clay, renowned photographers who have exhibited their work around the world. But what they see in the mirror today is entirely less romantic: They are caretakers of a decaying Mississippi mansion, an old wooden box that has become too expensive for a pair of artists to restore.

Sometimes, particularly in the South, the old wooden boxes that contain our lives become members of the family, as indispensable as brothers, sisters, mothers and fathers. We stand by them until the bitter end. Anyway, that’s what I’ve learned from Maudie and Langdon.

Top: Annie "Mook" Gipson and Maude Clay. Bottom: Sign painter. Photos by Langdon Clay

About the time Maudie was taking pictures near and around Sumner for a collection of images that became the award-winning 1999 book “Delta Land,” I was working out my teenage angst at an arts high school in downtown Tampa, Fla. Aside from its geographical placement, Tampa is arguably not “the South” people refer to in quotations. For one, there were no Southern accents, and most of our neighbors were from New York or some other cold-weather state.

During a lecture one day, my photography teacher swooned over a copy of William Eggleston’s “The Democratic Forest,” a tome of his images depicting the Deep South, particularly the Delta and Memphis. In a Boston accent tinged with a lisp, she pronounced the author of the book “the father of modern color photography.”

I was stunned that such a title would be given to someone born in a state I had heard about only in reference to the 1988 film “Mississippi Burning,” if mentioned at all. Like many people who draw conclusions about things they know nothing about, my perspective was narrow and naive. Throughout that course, our teacher inundated us with photographs by Mr. Eggleston, as she preferred to call him, but they had no effect on me.

“What did you think of his home?” she’d ask us.

My jaded 16-year-old self scoffed: “Have you ever been there?”

In French there is no word for home. There is, of course, the term “maison,” which refers to the structure people live in, but there is no definitive word to explain what philosopher Gaston Bachelard calls our “corner of the universe,” or “home.” As snarky as my comment was at the time, there was some truth to it. To understand the “home” that Eggleston depicted, I would have to live it.

If ever there has been a place whose significance in my life is proportionate to tears shed, it’s Mississippi. I moved to the Hill Country town of Oxford in the northwest corner of the state for love when I was 19, only I never told people that story. Instead, I made up other, more pleasant stories. The narratives I wove made a beautiful Spring the temptress or hinted at wanderlust, with either version ending in an eye roll.

My first job in Oxford was at a Greek store where I emblazoned girls’ names in pink and purple bubble letters alongside their sorority insignia. For a girl who once wore combat boots and knew every song by the Cure, the job gave new meaning to the phrase “It’s all Greek to me.” Square Books, the legendary bookstore founded by Richard and Lisa Howorth, offered me salvation a month into my purgatory, and I traded the paint pens and plastic cups for shelving the words of William Faulkner and Barry Hannah.

Barry Hannah. Photo by Maude Clay

Faulkner’s spirit may have haunted the bookstore, but at the time, Hannah was a living, breathing regular in it. It was upstairs in the cafe, where dollar coffees and advice were dispensed, where I met him. Barry wore a leather jacket and rode a motorcycle, and he prefered his coffee “candied up” with sugar and cocoa. One day when while I was making his hot mocha, he’d asked me what I was going to do with my life. We hadn’t known each other long. I just stared at him blankly. He said, “Don’t be a dilettante.”

One job was not enough to cover school and rent, so I also worked a few days a week at Southside Gallery, just two doors down from the bookstore. I don’t know exactly when I met Maude Schuyler Clay, but I am certain that after seeing her photographs on the wall, this was where I fell in love with her.

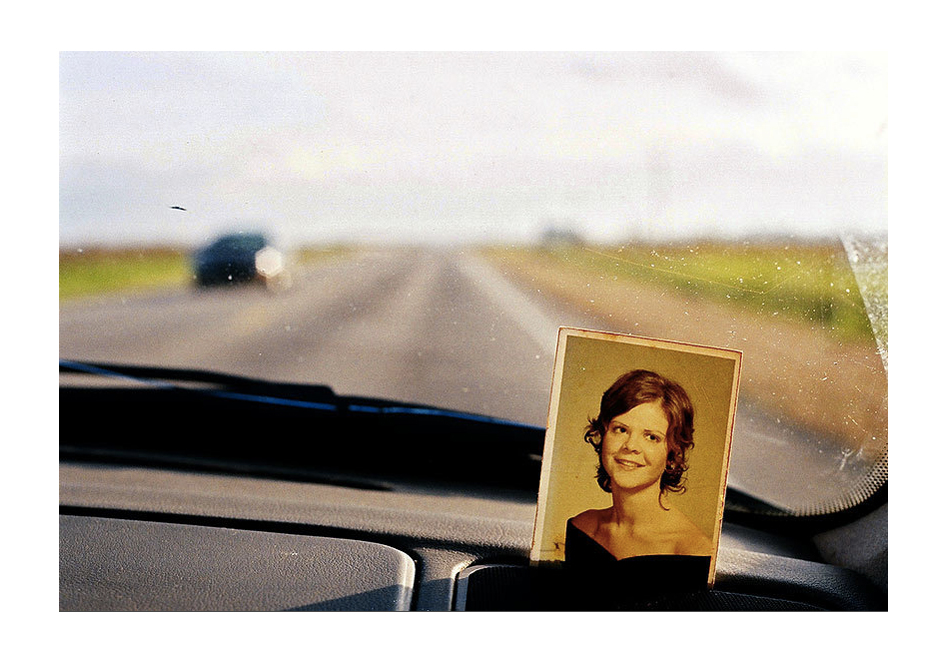

It was simple. While most kids' dads pushed sports, mine pushed film. In fact, both my parents were amateur photographers in their 20s, and while my mom’s hobby was eclipsed by raising six kids, my dad still found time to wander. There was the epic trip to Alaska to work on the pipeline and a tour of duty in Germany that resulted in a cache of images that became the backdrops of my dreams. But it was a black-and-white photograph my dad took in the 1970s, before I was born, that I remember the most. It traveled with me to Mississippi, an odd talisman that connected me to my dad, and it now hangs in my dining room: It’s a picture of pair of goats. A calm similar to the one I felt looking at my dad’s goats washed over me when I first saw Maudie’s photographs of dogs. It kind of felt like home.

Contact sheets for "Dog in the Fog." Photos by Maudie Clay.

Portraits of, top to bottom, William Eggleston, Lizzie Flowers and Jab Flowers, by Maude Clay.

The photographer’s eye runs in Maudie’s family. Her first cousin, the aforementioned William Eggleston, almost singlehandedly legitimized color photography in the eyes of American museum curators in the 1970s. Their grandfather, Joseph Albert May, taught his grandson to develop film, and Eggleston was a teenage photographer by the time his cousin Maude Schuyler was born in 1955. Both spent their youth running around the house in Sumner, which Joseph May had built in 1911, and they spent their summers about 10 miles west on his Mayfair plantation, which abutted the notorious Parchman Farm, Mississippi’s state penitentiary.

Today, photographs by both cousins are part of the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art and many other museums.

Maudie was actually born in the little hospital in Greenwood, about 45 minutes south of Sumner. Greenwood today is something of a culinary destination because Viking put down roots there in the 1980s to manufacture high-end kitchen appliances. But in the 1950s, when Maude was a child, its Main Street was both a highlight on a prominent list of the 10 most beautiful streets in America and a hotbed of fervor in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement.

A snapshot of the scene at the time might be called “Beauty Juxtaposed to Decayed Morality.” Following the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. The Board of Education in 1954, which declared that states could no longer establish separate public schools for black and white students, a local plantation manager named Robert B. Patterson crawled out of the netherworld to create the White Citizens’ Council to fight against racial integration. Soon after, new chapters of the organization cropped up to uphold the agenda of the Ku Klux Klan. Whereas the Klan’s modus operandi was violence, this new group used its economic and political influence in an effort to dismantle “agent provocateurs who came for the avowed purpose of breaking the law, violating orderly racial conduct and causing trouble.”

Despite a steady stream of immigrants to the Delta — a melting pot of Italians, Jews and Lebanese — it was still commonplace at the time for black townspeople to jump off the sidewalk to let a white person pass. Resistance to desegregation was a community affair, and there were plenty of ringmasters to lead the circus. So deep was the resentment of the change sweeping across America, specifically in their backyard, that a rival Delta debutante committee emerged.

Maudie remembers hearing about it through the whispers of her mother, who was a member of the Delta Debutante Club in Greenville, Miss., about an hour southwest of Sumner. The year was 1961, and the Club had invited distinguished guest Hodding Carter Sr., a Nieman Fellow and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, to be master of ceremonies for the season’s festivities. Carter also ran Greenville’s Democratic Times, and had begun publishing a series of editorials that illuminated the dark unrest taking hold in Mississippi against the Civil Rights Movement. In an article Maudie meticulously researched and wrote a few years ago, she tells how Hodding Carter Jr. recalled a visit to his parents’ home from “three or four white-gloved ladies of the Greenville area” who told his father that his inclusion in the upcoming debutante ball was causing a rift and that “if he were a gentleman, he would resign.” He didn’t, and those who were unhappy with his refusal to step down formed the Southern Debutante Assembly. Clearly manners had nothing to do with humanity.

“It was really a world that, as a kid, I just didn’t want to go there,” Maudie tells me today with a note of weariness in her voice. She is talking about the mental place in which she found herself after she heard about these activities, which seemed hardly nefarious in contrast to the murders of Emmett Till and Medgar Evers during the same era. And yet, the mentality of the people behind these acts was really all the same.

“It was probably like in Germany when you heard something about the Holocaust,” she says. “You just didn’t want to believe that people were really capable of doing that sort of thing, especially people that you knew.” We are talking on the phone one late winter afternoon. She tells me a story of how Fannie Lou Hamer, a key organizer in the Mississippi Freedom Summer for the Student Nonviolent Committee, came to Sumner. Among the people Hammer connected with were Jab and Lizzie Flowers, an African-American couple who worked on Mayfair plantation, which was accessed through Parchman Farm. Jab was Mayfair’s lead tractor driver. Lizzie was a housekeeper.

Photo by Maude Clay

“They must have had this completely dichotomous life,” Maudie tells me. “That was in the day where you put your life in your hands. Not only would they send you in exile from where you lived, but they could kill you for that sort of thing.”

Upheaval continued, and the Civil Rights Movement’s center shifted to Greenwood. When the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. visited the town in 1963, the Ku Klux Klan retaliated with a vindictive epitaph: "You have chosen your beds and now you must lie in them.” The manipulative wordplay sent a strong message to dissenters, as well as the silent tribe. The Schuylers were among them.

Adyn Schuyler, Maudie’s father, came from what his daughter calls “a nice family," but she’s quick to point out that he was a Yankee, a designation which to this day leads her to believe that "he was not involved in any of that racist crap.” He studied law in Illinois and took his first job in Memphis, where he met Maudie’s mother and namesake, Minnie Maude McMullen May, at the Memphis Cotton Carnival. She was dressed as a harem girl, a detail that doesn’t seem so odd when you know that before she returned home to Mississippi and made her cotton-fair debut, she had lived in New York City and been a model for the haute hat designer Hattie Carnegie.

The couple set up home in Mississippi and eventually had three children. They had servants, a driver and a summer house with a pool on Minnie Maude's father's Mayfair plantation. It wasn’t the typical American household, but it was typical for a certain set of Southern white landowners. Maudie acknowledges that there were two separate histories that played out in the Delta then: One was white, and one was black.

Photo by Maude Clay

Despite the political and social upheaval of the time, Maudie felt cocooned in a house filled with love and respect for the people who called the place home, whatever color they were. Her perspective, although myopic, afforded her a sense of security that nurtured her growth as a young woman.

“That might be one of the reasons why I wanted to come back to this house so much,” she says, “because I had very pleasant memories of having grown up in it.”

And yet, as talented young Southerners often do, Maudie left. Her first stop? Mexico. It’s not exactly the kind of trip you’d expect a young woman in the early 1970s to make without a frame of reference, and so of course, Maudie had one. She left the University of Mississippi to study at Instituto Allende in San Miguel de Allende, an art school.

Her cousin Bill, as she calls him, was “the most interesting man in the whole family.” She remembers him as an introvert with an interest in electronics, a kid who built a set of six-foot-high speakers and drove around town in a Ferrari. So when Maudie finished classes in Mexico, she begged her parents not to send her back to Ole Miss; instead, she went to Memphis Academy of Art and apprenticed with Bill.

During that period Maudie and her cousin Bill spent a lot of time driving around the back roads of North Mississippi, the Delta and the rough streets of Memphis. More than trying to show Maudie how to capture the “magic hour” that photographers call the late afternoon light, Bill was inadvertently giving his young cousin an education about wandering, and what it meant to be free.

Photos by Langdon Clay.

It makes sense that New York City came soon after. I suspect the same insatiable curiosity that now drives Maudie to point her lens at the landscape and people around her was what compelled her to hop in her friend’s car one day and drive to New York City with little more than a suitcase.

“Every egomaniac from every small town in the world goes to New York and tries to make it a reality. I pulled it off for a pretty long time.” From 1974 to 1987, to be exact.

Her mother’s shadow was long, but Maudie cast her own. She got an 1,800-square-foot loft two blocks from Madison Square Park for $650 a month, and landed a job at an art gallery. Over the next 13 years, she worked as a photo editor for Esquire, Fortune and Vanity Fair.

Not bad for a Delta girl.

“Everything was right there,” Maudie says of her time in New York. “But to me it was just not really home, even though I made a great home.” She went to Off-Broadway shows, hosted dinners and made new friends, many of whom she still keeps up with today. In the summers and in between jobs she went back to Mississippi. She made her pictures and returned to the city to pick up where she left things.

And then she met Langdon. The story went something like this:

Maudie was dating a well-to-do Jewish guy whose family’s name is carved into the the walls of the New York Public Library. After invoking the proverbial “need to find himself," he left for California, leaving Maudie behind.

“He just left me,” Maudie says, drawing out the “me” for sympathy, the way she might have told close friends at the time of his departure those many years ago.

I’ve seen pictures of Maudie then, a lithe beauty bearing a vague resemblance to a young Edith Piaf. She was equal parts mysterious and open, her face writ with the delicate script of possibility. In the shadows of New York’s skyscrapers, Maudie may have been small and dark, but like a black sequin, she sparkled.

It wasn’t long after Mr. Library left when she caught the eye of Langdon Clay, also a photographer, but very much a Yankee. She still gushes — with a hint of sarcasm that only being married to a person for decades permits — that their date was the best night the 20-something version of herself had ever experienced. Certain he was “The One," she blew out the flame for her unrequited lover and lit a new match for Langdon.

Only Langdon disappeared. He didn’t call, and for a long time, she never heard from him. When she told me this story, I had just relayed a similar tragedy of my own about a guy’s disappearing act.

Langdon Clay sitting with William Eggleston. Photo by Maude Clay.

In so many of Maudie’s stories you could replace her name with mine, especially as they pertained to love and photography. Photography, which she claims saved her from experimenting with drinking and smoking pot “because you know how kids are,” had been the Redeemer in my own life. Just replace Bill with my older, more mature friends with whom I’d shoot on the weekends. Replace the Mississippi gloaming with Florida sunsets, and replace Bill’s studio darkroom with the Camera Hutt in Tampa, a photo lab where I earned the nickname “black and white girl.” If our lives are truly parallel, then marriage to a man I deeply adore, despite a stalled start, is in the cards, because after Langdon’s disappearing act, he returned and married Maudie.

In 1987, she took her Yankee husband and moved home to Mississippi.

I was in my mid-20s when I was first invited to visit Maudie and Langdon at their home in Sumner. I saw Maudie and Langdon often because I worked in the bookshops and galleries on Oxford Square, and kind words between us had become friendship. To this day, neither Maudie, nor Langdon nor I can recall how the invitation came, but we all agree it involved food, like any Mississippi gathering. A dinner party to be exact. Langdon remembers my arrival, stopping and slowing down in front of each house on the street until I ended up pulling into their driveway. I came with a friend, a chef from Oxford, and we brought part of the meal. Langdon was perched on the second-level balcony fixing an outdoor light.

I don’t know what I expected, but what I saw was a pair of glossy magnolia trees framing the gray facade of an aging, clapboard house. On the balcony behind Langdon, I saw a trio of French doors punctuated peeling boards, and below it, a screened porch jutted out, the proud chin of this house that still seemed to glow.

Later in the day, Langdon showed me pictures of a young William Eggleston romping around one of the rooms. During dinner the phone rang and they let the machine answer it. We all froze after the beep to listen to the curious voice on the machine. “Oh, it’s Bill,” Maudie announced unaffected, “let the machine get it.” And we began to slice into her spaghetti pie.

There are moments in life that seem to affirm the path you are on is the right one. Dinner that night was one of them. I was never a fan of Eggleston’s work the way my teacher was. I had filed his name away with my diploma the moment I left high school. And yet somehow he had played a role introducing me to Maudie. I’ve still never been able to thank him for it.

I stayed at the Clays’ house that night, and while lying in my bed unable to sleep, I wondered what it was like to be the caretaker of the place where William Eggleston once dreamed, a place where now Maudie dreamed, too. All that weight, and so much waiting. Why did she come back? And how did she get Langdon to come with her?

There is a scene in William Faulkner’s “Sanctuary” where in a moment of compassion, lawyer Horace Benbow invites a woman and her sick child to stay with him in the house he shares with his sister Narcissa. She objects to his gesture — the woman has a scandalous past — but it’s a comment she makes later, in a quiet moment, that stuck with me: “I don’t care where you live. The question is, where I live. I live here, in this town. I’ll have to stay here. But you’re a man. It doesn’t matter to you. You can go away.”

Langdon could go away when he needed a disappearing act. He was free to do so.

But Mississippi had never released its hold on Maudie. She had to come back, so she did.

Maude Clay. Photo by Jerry Siegel.

Everyone says Faulkner’s books are sketches of Oxford, but beyond portraying its people and scenery, he depicted its sentiments and customs, too. Not much has changed since he wrote that book in 1931. The homes I lived in — at least 10 different ones over the seven years I spent in Mississippi — seemed to need me, too. There was the professor’s house I stayed in while she taught in France. The apartment I kept for a woman who wanted a place as a back-up in the event she was left homeless by a failed relationship — again. And my first home in Oxford, which I did my best to keep immaculately clean only to leave it stained with the memory of finding my love in our bed with another woman.

I took great care of the houses I lived in. The people they belonged to seemed to need me even more than they did. I still feel attached to the places I lived in during my Oxford years, just as Maudie remained drawn to her childhood home. When she and Langdon first moved to Mississippi in 1987, they settled into a home her parents rented for them on the other side of the bayou. While they lived there, Maudie gave birth to Anna Booth, the first of her three children. Then, in the midst of welcoming new life into the world, there would be an exit. Her mother, already diagnosed with multiple myeloma, passed away, leaving behind her father and everything else in their home. That’s when Maudie and Langdon and their family moved back across the bayou and into the old house, where they remain.

There must be a formula for the amount of time it takes for you to grow unattached to an object. Perhaps it’s the strength of attachment times the length of time you’ve spent with it. If you could apply that formula to most of the things Maudie inherited in her childhood home, the result would approach infinity. Whereas most people would have relegated decade old knick-knacks that never really belonged to them to the shelves of the local Goodwill, Maudie created a museum, or mausoleum, as she jokingly calls it, and continued to acquire new things thanks to eBay. Langdon, too, has contributed his fair share. He’s a “lifer,” Maudie says, meaning he is happy in the Delta with his garden and the open roads.

Photos by Maude Clay.

Today, in their home, there is a collection of taxidermy on table tops and mantles, while walls are adorned with colorful paintings by her mother Minnie Maude, photographs by her cousin, husband, herself and friends like Sally Mann. Despite its exterior decay, inside the house is all gilt and finery and Southern ephemera. With this house, the inside is what really counts.

In the kitchen, there are several painted roadside signs urging folks to repent, and if anyone is going to be irresponsible that night, there is another sign to remind you that “abortion is murder.” Throughout the house, Oriental rugs lie scattered about, one on top of the other, worn from decades of impromptu dancing and babies’ bottoms, like Bill’s, scooting across the floor. There are carved table legs set with centuries-old marble and topped with sepia-toned portraits. But my favorite thing in their place has always been Maudie’s dogs, which give the space another layer of life. Today, they have three. Four, if you count the one that just eats and occasionally sleeps there.

Grain Elevator, Drew, Sunflower County, Miss. Photo by Maude Clay.

I’ve always been fondest of Zelda, whom I met just before I left Oxford. She was a rescue who reminded me of my dog Emileigh, a lemon beagle mix I adopted and named for the bakery she was found behind, eating cake. I took Em to Atlanta with me and she became my living, breathing connection to Mississippi. Pulitzer Prize-winning "Kudzu" comic-strip creator Doug Marlette and I may have affectionately called each other “ambivalent Southerners," but I finally claimed the state as my home when I found myself defending it outside her borders. Suddenly, Maudie and I also had something else to talk about. At that point, Maudie’s book “Delta Land” had become a bestseller in the Oxford bookstore, but it was a photograph of a dog in the misty bayou standing alert on a log within its pages that spoke to me.

It is believed that the cohabitation of dogs and humans, and later the domestication of dogs, may have been one of reasons early humans survived. Among other things, dogs assisted with hunts, thus sustaining the lives of the humans who kept them. Maudie began inadvertently photographing dogs in the 1990s. As she was going through old negatives one day, she noticed that her photographs of dogs held their own against the dilapidated kudzu mansions she is widely known for capturing.

There were enough accidental dog portraits that she decided to put together a book called “Delta Dogs," and at the time of writing this, I was nudging her along in the process of scanning negatives to meet a spring publication deadline. I asked her about the work. She was sorting through more than 800 negatives.

“You know, I’ve often said I feel more for the dogs than humans a lot of the time,” she says. “If I see a hungry or or hurt dog it’s just an automatic ‘I need to help this creature.’ Basically you have to do the same thing for humans, but for some reason the helpless animals really tug at me.” I feel the same way about homelessness, which may explain one reason why I obsessively write about the topic of home.

Bruce Springsteen once said that he writes as a way to understand things. In the same way, I see Maudie collecting, focusing on and organizing images as an exercise in grasping the role she plays in the lives around her. This may be where her compassion for dogs stems. When I joke that maybe she was a dog in her past life, her response is a meditation:

“Maybe that’s how I’ll be able to live forever,” she says. “All the old black dogs wandering around. I’ve often thought of that eternal question of why we’re here, what are we doing, all that heavy stuff. I often think, if I were to come back as something, what would it be? And I started thinking it might be one of these Delta dogs, or maybe just a dog.”

"Delta Dogs" by Maude Clay.

Like Maudie, domesticated dogs always come home. Yes, they roam the land finding adventure, splashing along river beds and harassing chickens, but as the sun sets and the stomach growls, the pooches always return. And they do something else. They protect. Just as dogs have evolved to ensure the success of their human family, Maudie must stay to take care of her home, which with its memories and ephemera lives and breathes the same way one of her relatives might. But what happens when Maudie is gone, when there’s no life support?

Maudie and I have talked about this with the kind of uncertainty anyone would discuss funeral plans for someone still breathing. Although she has already clipped an obituary she plans to copy for her own and posted it to her fridge should anyone forget, there’s a bigger question: What will they do with all her books?

“That will probably be the biggest problem of all when I die and they have to get rid of all this stuff,” she tells me. All three children are out of the house, making lives of their own elsewhere in the world. One even left the South.

I ask her what the South means to her, and after she reminds me that I’ve just asked a loaded question, she tells me it means home. Mythologies abound with iterations of the maiden, the mother and the crone coming together to create a circle of life. Maudie’s life represents a triad too. Her vision of three women completing a cycle — her mother, herself and her daughter — brought her back to Mississippi for her own homecoming. While I love to imagine Southerners invented that sacred word “home,” what I am certain they continue to cultivate, through sacrifices like the one Maudie made with her return, are places that protect memories and time.

Leaving is also a necessary part of defining home. After Mexico and New York, Maudie returned. “I’m back in the same place where all these people have been for a very long time, at least three generations,” she says. “There is something kind of secure about that, if not insane.” She describes a door in the butler’s pantry that has creaked the same way all her life, if not since when the house was first built. Its eeking sound is white noise to her ears, and she’s not inclined to fix it.

“I guess I’m not somebody who loves change, and this house makes me feel very safe.” Safety and shelter form the foundation of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, and the Cassidy Bayou home provided her with both, so that she could feel safe enough to leave and explore, and ultimately grow.

I bought my place in Atlanta with one thing in mind: freedom. It’s an odd and fitting coincidence that the community I bought in is called Freedom Heights, just a few streets from where Martin Luther King, Jr. once preached at Ebenezer Baptist Church, rallying the battle cry of civil rights heard around the world.

I remember the first night I slept in my house, on a mattress on the floor, a soldier fighting for another kind of change. An angry rain fell hard on the roof that night and woke me up. For a moment I was scared, having mistaken it for gunshots, and once that fear subsided I remained anxious. I was alone in a home I had committed to. But that fear didn’t last long either, because as the rain grew silent, I realized that I would never again be without a place to return to, to feel safe. My home became my sanctuary. Maudie's house is, too.

A few years after I had moved away from Mississippi, I visited Maudie and Langdon. That afternoon, we drank from crystal and sat in the middle of the kitchen at a table set with the family silver and fine porcelain. Lunch was a puree of near-spoiled vegetables and cream — they didn’t know I was coming — and good conversation. I don’t remember what we talked about, but I know it had something to do with my travels in the world. I had been to Paris and London, and several cities in the U.S., though I still preferred the South, and being away from it reminded me so. I was glad they were there waiting for me, ready to take care of me, just like all the other things under their roof at that moment.

Dog in the piazza, by Mary Warner.

The year after Maudie and Langdon stayed at my Atlanta home, I was in Italy again. This time Florence. After my work, I had no itinerary other than to wander the ancient streets, and at sunset I found myself in front of a building burning bright. It was Santa Croce, an ancient Franciscan church that anchors a piazza off the main pedestrian drag, a place I had stumbled upon the day before. I thought a photograph of the place would help me remember the feeling of being free, of living life on the edge, of wandering. A bright white church in an open area also seemed vaguely familiar. Just as I was taking the picture, a black dog wandered into the corner of the frame. It was too late. I looked at the picture and there was Maudie. It was as if one of her Delta dogs had followed me across the sea.

Later that night going through my images of the day, I understood for the first time a bigger lesson my friend had taught me: We also carry our homes inside us. I sent the image to Maudie, but it almost seemed I didn’t have to.

Next Week:

Nashville

Lawson Little has spent almost half a century photographing the stars and the underrated of Nashville’s eternal country music scene. On Tuesday, we’ll bring you a collection of Lawson’s greatest hits — some of his most memorable images.